Equal Under the Law

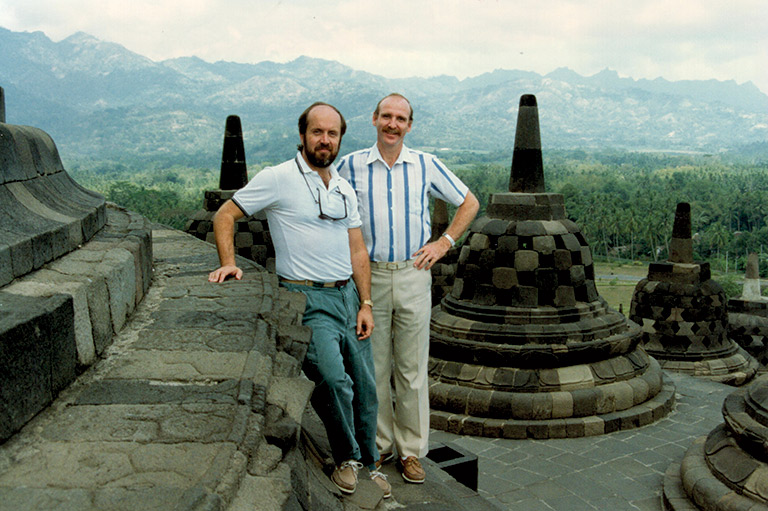

When foreign service officer Stanley Moore was posted to Indonesia in 1991, he applied to Canada’s external affairs department to cover relocation expenses for his partner, Pierre Soucy, and their Himalayan cat, Lady Jasmine. The department agreed to cover the expenses for the cat — but not for Moore’s same-sex partner. In that instance, Soucy later recalled, the feline “had more rights and status than me as a gay man in Canada.”

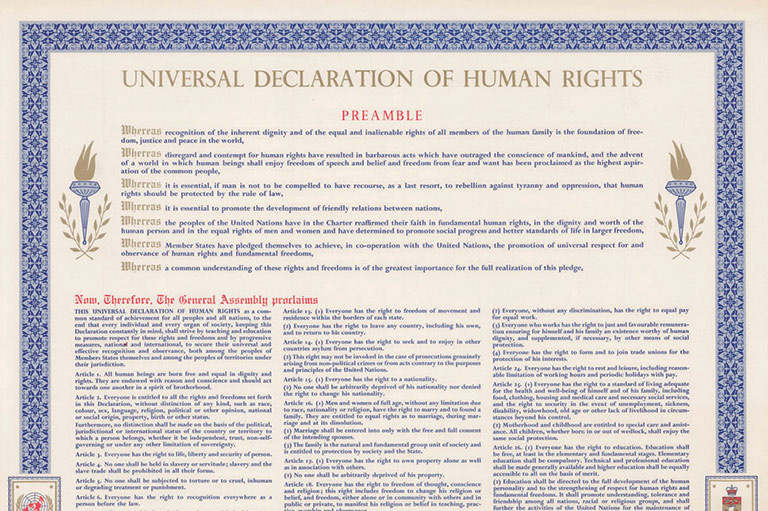

This year marks the 25th anniversary of a pivotal law that expanded the definition of “spouse” to include same-sex partners — and marked a major step on the road to the legalization of gay marriage. The Modernization of Benefits and Obligations Act, which received royal assent on June 29, 2000, amended 68 federal statutes — affecting such day-to-day issues as pension and death benefits, bank loans and income-tax deductions — to give gay and lesbian common-law couples the same rights and responsibilities as their heterosexual counterparts. The principle of the law, in its own words, was “to reflect values of tolerance, respect and equality, consistent with the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.”

But these changes would not have happened had it not been for people like Moore and Soucy, who exposed their private lives to public scrutiny to fight a years-long legal battle. During debate in the House of Commons, NDP MP Svend Robinson argued that the proposed law was “not about special rights for anyone. ... It is about fairness and equal rights. It is a recognition that gay and lesbian people pay into benefit plans and, up until very recently, have been denied the benefits that should flow.” And he named Moore and Soucy among the “unsung heroes” of Canada’s LGBTQ+ community who fought a “courageous fight for full equality.”

Article continues below...

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

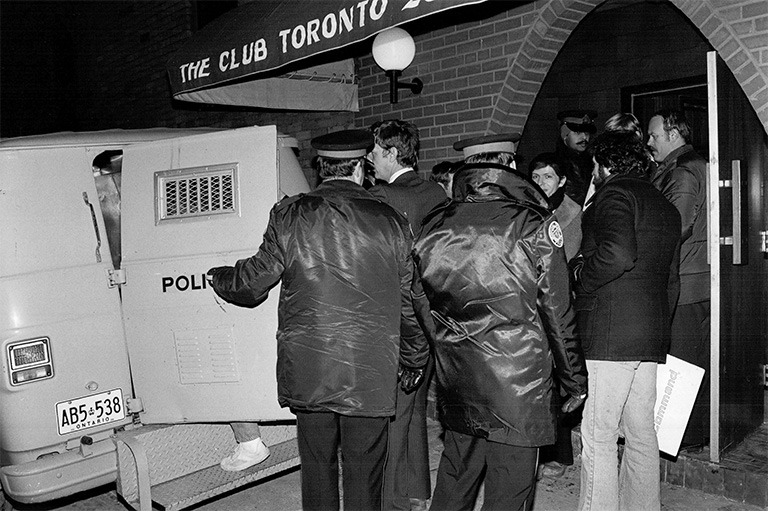

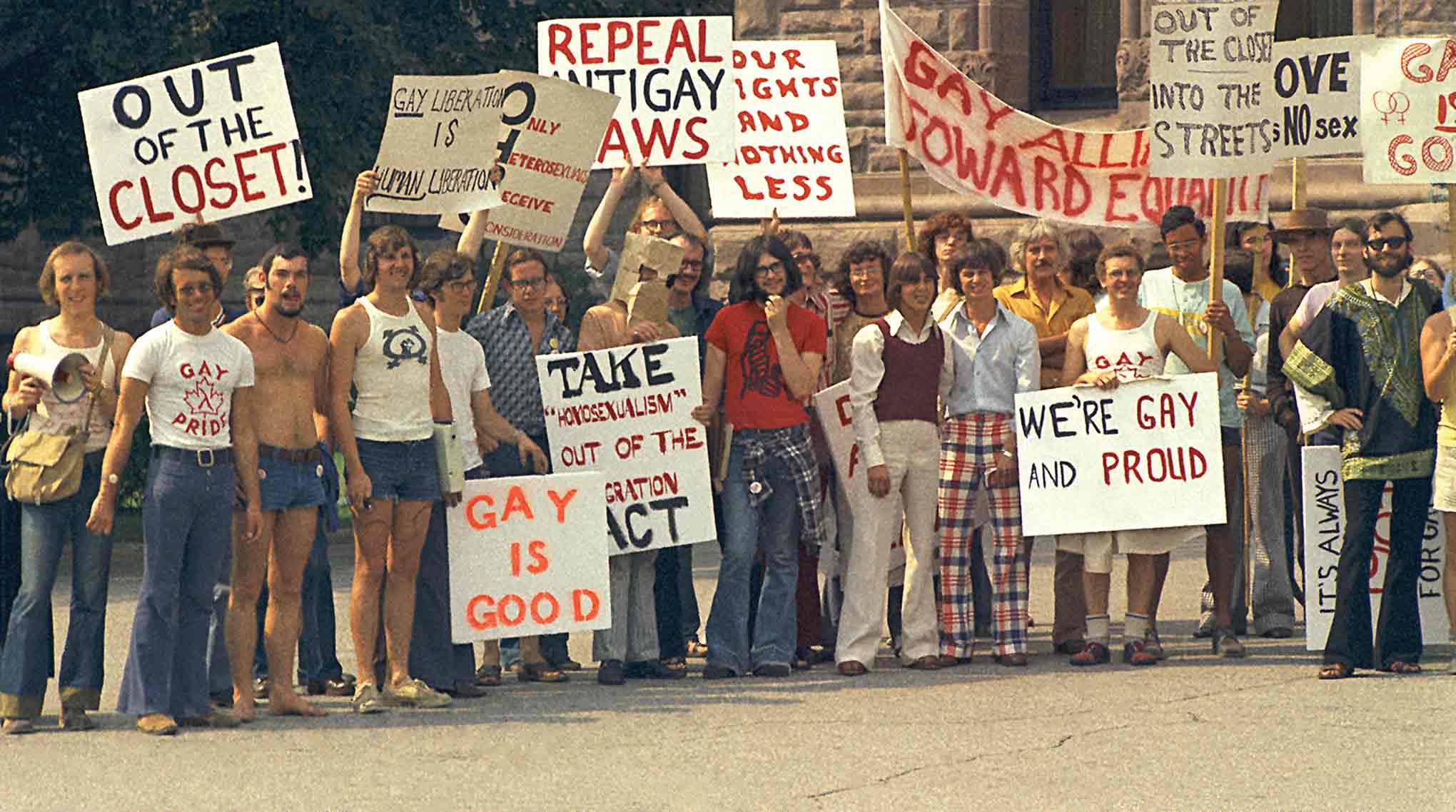

It would have taken courage for Moore to tell his employers in 1991 that he was gay. Homosexuality had been decriminalized in 1969 in Canada, but legal and social equality was still a long way away. In Toronto, massive police raids on gay bathhouses in 1981 sparked protests, galvanizing the LGBTQ+ community to become more active and organized. Pride parades sprang up in various Canadian cities, but often faced social backlash.

The AIDS epidemic, which arrived in North America in 1981 and raged until the 1990s, hit sexually active gay men especially hard, and made same-sex relationships a matter of emotionally charged public debate. The ravages of the disease elicited compassion among many, especially as popular figures like actor Rock Hudson, ballet dancer Rudolf Nureyev, rock-and-roll singer Freddy Mercury and pianist Liberace succumbed to the deadly virus.

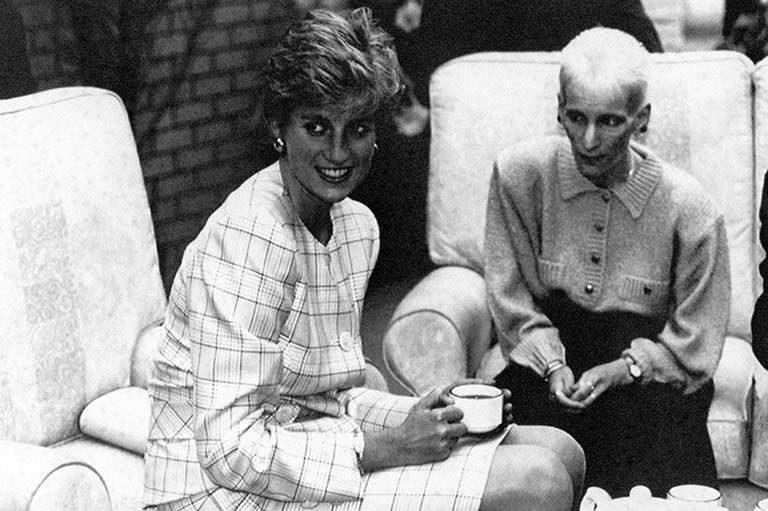

The United Kingdom’s Diana, Princess of Wales, made international news in 1987 when she opened an HIV/AIDS ward in London Middlesex Hospital and shook the hand of an HIV-positive patient in front of television cameras. When Robinson, the Member of Parliament for Burnaby, B.C., came out in 1988, he became the first openly gay parliamentarian in Canadian history.

But the epidemic also added fuel to the fire of social conservatives, especially Christian evangelists who preached that homosexuality was sinful. Popular American preachers like Billy Graham suggested that the AIDS epidemic was God’s punishment for homosexuality. In Canada, the Alberta-based Reform Party, founded in 1987, opposed gay rights, and party founder Preston Manning, an evangelical Christian, was against homosexuality on religious grounds. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, various Catholic and evangelical Christian groups continued to fight against equal rights for gays and lesbians.

Moore was 44 years old and had been living with Soucy for two years when he was deployed to Canada’s embassy in Indonesia for a two-year posting as a counsellor for development and economics. Soucy, then 42, took a leave of absence from his job in the federal public service to accompany him.

Before the couple left for Jakarta, Moore spoke to an official with External Affairs and International Trade Canada (now Global Affairs Canada) about spousal benefits. He was taken aback by what he heard. “He was exasperated by my insistence that Pierre’s expenses should be covered and finally said to me, ‘You really should be happy that we’re even allowing your type to go abroad,’” says Moore.

While the couple was in Indonesia, the collective agreement between the Treasury Board and the Professional Association of Foreign Service Officers was modified to include a clause stating that there would be no discrimination based on sexual orientation. So, Moore reached out to officials at External Affairs and requested coverage for Soucy under the Foreign Service Directives, including his relocation expenses and health-care costs.

“We were told that was not the intent of the clause,” recalls Soucy. He says that he and Moore then asked External Affairs what the intent was. “We never got a response. That got our dander up.”

Says Moore: “I think Treasury Board simply saw it as a statement of goodwill, but not as an obligation — and were probably startled when they realized there were implications in it.”

On the advice of his professional association, Moore filed a complaint with the Canadian Human Rights Commission in 1992. When it was rejected, he filed a second and then a third. “Most people would have given up at this point,” says Moore. “But in my case, it just did not make sense that I would be rejected.”

In 1994, the commission decided to refer Moore’s case to the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal, while combining it with the case of another federal public servant, Dale Akerstrom, who had also been denied benefits for his same-sex spouse, Alexander Dias.

Akerstrom wanted to change his benefits status under the Public Service Health Care Plan from “single” to “family” to include his partner. But his request for the change in coverage was rejected because “spouse,” under the terms of the plan, was defined as a person of the opposite gender.

“Ours was the test case,” says Moore.

Advertisement

As Moore’s case made its way through the legal process, things were changing in Canada’s judicial and political landscape. In October 1993, Jean Chrétien’s Liberals won the federal election, putting an end to nine years of Conservative rule. In the riding of Vancouver Centre, physician Hedy Fry defeated Prime Minister Kim Campbell to take the seat for the Grits.

Fry, who is now 83 and still serving in the House of Commons, says she became acutely aware of the discrimination facing members of the LGBTQ+ community when she treated AIDS patients in the 1980s. “I would be there with these young men in their 20s, holding their hands as they died, and was appalled at the fact that they had no rights at all.”

“A heterosexual common-law spouse could come into the hospital and make decisions about funeral arrangements and medication for their spouse. Gay couples did not have that ability. Parents who had abandoned their sons or daughters because of their sexual orientation came in and made medical decisions, which probably wasn’t what the person wanted. That, for me, was a very hurtful thing,” recalls Fry, who went on to serve in Chrétien’s cabinet as secretary of state for multiculturalism and the status of women and is the longest-serving female MP in Canadian history. “These were human beings who were being denied the ability to be equal under the law.”

She says she told Chrétien that she wanted the Canadian Human Rights Act amended to add sexual orientation as a prohibited ground of discrimination. “It was what I ran on in 1993,” she says. “He said he could do that — gave it to me in writing — and we did.”

Meanwhile, in the first half of the 1990s, a number of cases were being argued in court that concerned the question of whether discriminating against someone based on their sexual orientation should be considered to be prohibited under the Canadian Human Rights Act and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Although sexual orientation was not explicitly included in either of these acts, lawyers successfully argued that it should be “read in” to the law because it was analogous to other prohibited grounds of discrimination like sex, race and religion.

The Canadian Human Rights Tribunal finally heard Moore’s case — combined with Akerstrom’s — in 1995, and released its decision a year later. Relying on recent court rulings, the Tribunal found that “sexual orientation is now a prohibited grounds of discrimination” under both the Canadian Human Rights Act and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and that “a definition of ‘spouse’ which excludes same-sex partners ... constitutes a discrimination prohibited by both [acts].”

The Tribunal ordered the government to pay compensation to both Moore and Akerstrom, and to amend several federal laws related to income taxes and employment benefits so that the definition of “spouse” was changed to include same-sex partners. The ruling, upheld by the Federal Court in 1998, was an important win for Moore. He says that he “never wanted a separate category just for gays, without using the word ‘spouse’” — he only wanted gay couples to be “treated as common-law spouses.”

In 1996, the Liberal government under Prime Minister Chrétien amended the Canadian Human Rights Act to prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. Then, in 1999, the Supreme Court of Canada issued a landmark family-law ruling in a case that involved two lesbian women who split up after living together for 10 years. In that case — known after the women’s first initials as M. v. H. — the country’s top court ruled that one of the women owed spousal support to the other after they separated, just the same as if they had been a heterosexual common-law couple.

In its ruling, the court declared the definition of “spouse” in Ontario’s Family Law Act unconstitutional, since it only included couples made up of a man and a woman. “The exclusion of same-sex partners from the benefits of the spousal-support scheme implies that they are judged to be incapable of forming intimate relationships of economic interdependence, without regard to their actual circumstances,” the court held. “Such exclusion perpetuates the disadvantages suffered by individuals in same sex relationships and contributes to the erasure of their existence.”

Less than a year after that decision — on February 11, 2000 — the Liberal government introduced Bill C-23, the Modernization of Benefits and Obligations Act, into the House of Commons. But although the government was willing to expand the legal definition of “spouse” to include same-sex common-law partners, there was one bridge that it was not willing to cross: changing the traditional definition of the word “marriage.”

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

On June 8, 1999, Members of Parliament had voted 216-55, in favour of a motion by the Official Opposition Reform Party of Canada to preserve the legal definition of marriage as “the lawful union of one man and one woman to the exclusion of others.” The governing Liberals, including Justice Minister Anne McLellan, surprised many and angered some by voting in favour of the motion. McLellan said the government had “no intention of changing the definition of marriage or legislating same-sex marriage.” In March 2000, a month after she introduced Bill C-23 in Parliament, McLellan added an amendment to the bill to reaffirm the traditional definition of marriage. Fry was the only cabinet minister who voted against it.

And so the Modernization of Benefits and Obligations Act drew a fine line — including same-sex couples in the definition of common-law spouses but excluding them from the definition of marriage. It wouldn’t be long before this conundrum landed once again in the courts and in Parliament.

On July 12, 2002, Ontario’s Divisional Court released a ruling in a case that involved several same-sex couples who had tried to obtain marriage licences from the Clerk of the City of Toronto. Halpern v. Canada (Attorney General) was the first court decision in Canada that found preventing “gays and lesbians from entering into the societal institution of marriage” was a violation of their equality rights under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The court ruled that the legal definition of marriage should be changed to the union of “two persons to the exclusion of all others.” Courts in Quebec and British Columbia soon made similar rulings.

On February 13 of the following year, Robinson introduced a private member’s bill that would legalize same-sex marriages. It was his third attempt since 1998, and, like the others, the bill failed. However just four months later, on June 10, 2003, the Ontario Court of Appeal upheld the lower court’s decision in the Halpern case. Seven days later, the Liberal government announced that it would unveil legislation to legalize same-sex marriage. By July, the government had prepared a draft bill and sent it to the Supreme Court for legal vetting.

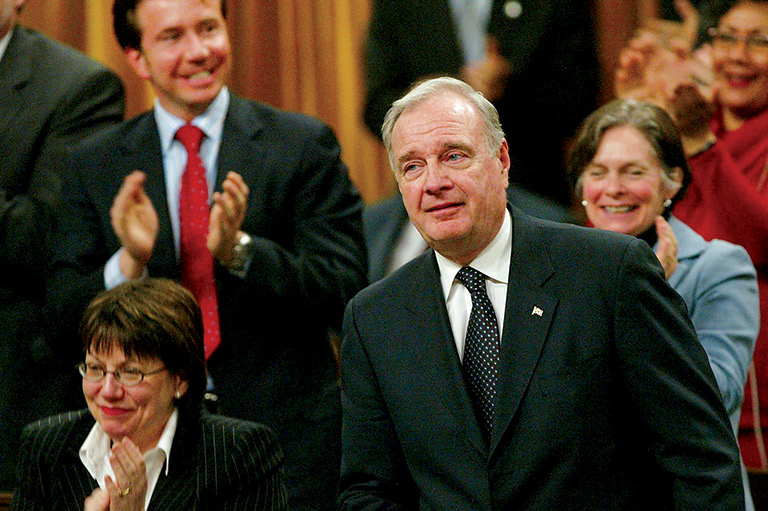

On February 1, 2005, Prime Minister Paul Martin, the successor to Chrétien, introduced Bill C-38, the Civil Marriage Act. It passed by a 158-133 vote in the House of Commons and received royal assent on July 20. Same-sex marriage was officially legal across Canada.

Moore and Soucy got married in 2004 and now live in Vancouver. Looking back, Moore says they feel “honoured and proud that our court case was instrumental in advancing the gay agenda,” and they hope that their story “will inspire champions of today and tomorrow to continue to push forward toward a vision of fuller societal and judicial acceptance.”

However, he cautions that “the hard work of generations can be undone in a flash, as witnessed by the rapid growth of regressive attitudes and policies south of the border.” Moore adds that, as the late South African Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, “reminded us, ‘The price of freedom is eternal vigilance.’”

In today’s environment of misinformation and disinformation, it can be hard to know who to believe. At Canada’s History, we tell the true stories of Canada’s diverse past, sharing voices that may have been excluded previously. We hope you will help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past, highlighting our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages – award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts. Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement