Confederation or Bust

Imagine Prince Edward Island, if you are not an Islander, you may think: What a charming place for a vacation! Trim farmhouses amid green fields, that famous red earth, and the shimmering blue sea beyond. That — and not just politics — is what the Toronto politician George Brown, one of Canada’s Fathers of Confederation, noticed on his first visit in 1864: “As pretty a country as you ever put your eye on,” he wrote. He rhapsodized about dining on “oysters, lobsters, and champagne” and “walking, driving, or boating as the mood was on us” amid the “most beautiful scenery.”

Brown was there to promote Confederation to the great political conference held from September 1 to 9 at Province House in Charlottetown. The conference brought together delegates from the Province of Canada (now parts of Ontario and Quebec), Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and P.E.I. to discuss the possible union of the British North American colonies. But Brown wrote about the island in just the same way as all the tourists who have travelled there since.

So it’s easy to imagine a pleasant, sleepy little colony that missed out on Confederation in 1867 just because no one got around to seizing the opportunity. Farmers and fishermen living in happy isolation — what would they know about constitutional proposals and nation-building ambitions? Anyway, the island was set apart from the mainland. Eighty per cent of Islanders had been born there. Maybe they just never really got the memo. Is that the explanation for why Prince Edward Island didn’t join Canada until 1873, making this year its one hundred and fiftieth anniversary of Confederation?

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

That’s not it at all. In the 1860s, Prince Edward Island had a lively political culture and a well-informed citizenry. Its citizens were the first British North Americans to have universal free public education, and they had the widest electoral franchise: In P.E.I. all adult males could vote, although women were still excluded. Opinionated local newspaper editors kept citizens well-informed, and news from British North America and the world was widely available. Members of the legislature knew that their constituents watched them closely and their seats were never safe. The issue of Confederation was not neglected. It was furiously debated in the colony from the moment the proposal for union was launched, early in 1864.

Before Confederation became an issue, Islanders battled over schooling policies, over the rivalries that divided the Protestant majority and the Roman Catholic minority, and — this was the big one — about who owned the land. Islanders had a land problem unlike any other part of British North America.

The land question bled into every other political issue and seemed to make them all insoluble: No government could satisfy P.E.I. voters for long. Thirteen different governments, headed by eight different premiers, struggled with the land question in the quarter-century from 1851 to 1876; a premier’s time in office averaged barely two years.

No one knew the challenges of the island’s politics better than George Coles. He was island-born, a farmer’s son who had become a successful businessman. He ran a retail store, a mill, a brewery, and a distillery. His neighbours were his customers. The better off they were, the more his businesses thrived. He and his British-born wife, Mercy, raised twelve children in their Charlottetown home. George Brown met their daughters at the 1864 Confederation conference and described them as “well educated, well informed, and sharp as needles.”

Like Premier Joseph Howe in Nova Scotia, like co-premiers Robert Baldwin and Louis-Hippolyte LaFontaine in the Province of Canada, George Coles had been an architect of self-government in his province. In 1851, when the autocratic governors sent out from Britain yielded their authority to elected representatives, Coles was the premier who took over the reins of power. Premier Coles made the most of the opportunity. His government brought in that wide electoral franchise. It was Coles who ensured that the P.E.I. government provided universal free public education to girls and boys alike. That little country schoolhouse Lucy Maud Montgomery wrote about in Anne of Green Gables? It was there for the fictional Anne and for real girls because of Coles’ schooling policies. But the system of land ownership was what really drove George Coles — a system that had been established a century earlier, following the Seven Years’ War between Britain and France.

At the end of the war in 1763, Britain replaced France as the colonial power on Prince Edward Island, having already expelled most of the island’s French-speaking Acadian settlers. As part of the process of making the island into a British colony, surveyors drew long diagonal lines across the island’s map, marking out sixty-seven great estates of about eight thousand hectares (twenty thousand acres) each. Those estates were handed out to well-connected British aristocrats, prominent military officers, and other good friends of the King and the British government. Since there were few inhabitants other than the Acadians and the Mi’kmaq when the estates were granted, and no local government that could resist the new order, there was no one who could effectively contest the suddenly acquired privileges of the new owners of the island.

The Acadian settlers who remained — and those who returned after the peace — were declared tenants of the new owners. No Acadian would sit in the island’s legislature until 1854 — and the one who finally did had to change his name from Stanislaus Poirier to Stanislaus Perry to make himself acceptable. The Mi’kmaq made treaties with the British Crown that guaranteed their hunting and fishing rights, but the great land survey ignored their presence entirely.

Most of the new landlords of Prince Edward Island never left Britain. They used local agents to manage their properties, and anyone who came to settle on Prince Edward Island was obliged to pay them rent forever. On a continent where all farmers felt entitled to own the piece of land they farmed, Prince Edward Island was an anomaly. There, a settler’s descendants could farm his rented lot for a thousand years and never own a handful of it themselves, nor would they benefit as its value increased. Most of those who became tenant farmers were impoverished emigrants from Ireland and the Scottish Highlands, who had been tenants back home and were unaware, when they settled on P.E.I., that nearly everywhere else in North America hard-working settlers could acquire land without having to pay a landlord.

As premier, George Coles could see that the tenancy system drained wealth from the colony, discouraged immigration and settlement, and hindered economic development. So he fought to end what Islanders called the “landocracy.” And he lost. The absentee proprietors had the law of property on their side; and the British government; and the island’s governors; and all the lawyers, land agents, and estate managers who made a nice living serving the proprietors while securing themselves seats in the P.E.I. legislature to resist reformers like Coles. The tenants had helped to make Coles premier because he promised to free them from what he denounced as “the baneful influence of the proprietors.” But the island government had too little money to buy out the landlords. Britain would neither advance the money nor allow the island government to attempt expropriation, even of neglected estates. Nothing happened. The tenants lost patience in Coles’ promises, and, when religious tensions divided the tenants’ votes, his party was defeated.

Advertisement

The landlords were still in control — and George Coles was still a member of the legislature — when the Confederation proposal took flight in 1864. The idea did not appeal to him much. He was an Islander; the problems of the Province of Canada, or even nearby Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, did not concern him the way those of his homeland did. Coles saw that many, perhaps most, Islanders thought Confederation would swallow them up and then ignore them, and he could find little reason to annoy his constituents again, just to please the other colonies. “We have universal manhood suffrage and an elected legislative council, but they have neither,” he said disdainfully about the other colonies of British North America. And it was true.

Unless … maybe the new Canadian nation could stand up to the property owners and their British backers more effectively than little Prince Edward Island? More important, maybe Canada would put up the money needed to buy out the landlords. Confederation itself was not popular among Islanders, but one anti-Confederation newspaper admitted that, if it could get rid of landlordism, “the Islanders almost to a man will hold up both hands for the union.” If Confederation could put an end to the landocracy, George Coles would give it a second look.

A generous offer that recognized and addressed the land problem could have won him over. It might have appealed to the long-suffering tenants, and even to the landlords, who would see the writing on the wall and be glad of a generous buyout. But when they went from Charlottetown to Quebec for the second Confederation conference from October 10 to 27, 1864, the Prince Edward Island delegates found that their proposal to fund the end of landlordism had dwindled to a vague possibility. The other provinces’ delegates seemed not to grasp how central the issue was to them — not even those from Lower Canada, which had abolished its ancient seigneurial landholding system barely a decade before. George Coles could not even get the issue put on the Confederation conference’s agenda.

Coles quickly concluded that Confederation would make the island’s situation worse instead of better. Before Confederation, every British North American province levied its own tariffs on everything it imported and exported. Long before there were income taxes and sales taxes, governments funded themselves with these tariff revenues. But under Confederation provincial tariff revenues would vanish. The new federal government would collect all the customs duties and tariffs at Canada’s new borders. Other provinces could still generate money from their Crown lands, whether by selling land or by collecting fees from resource industries. But the island’s land belonged to the landlords, not to the Crown. The P.E.I. government would have neither tariff revenues nor land revenues to support itself once it became part of Confederation. “See the pitiable state to which this island would be reduced under Confederation,” Coles declared soon after the Quebec Conference. “Our revenues taken away, scarcely enough allowed us to work the machinery of the local government.”

George Coles returned home from the Quebec Conference in November 1864 dead set against Confederation. He campaigned for re-election on an anti-Confederation platform. On that issue, many of his long-time Tory rivals, the defenders of the landlords, agreed with him. The anti-Confederates declared that the island would be swallowed up in Confederation, only to have huge new taxes imposed on its people. They argued that P.E.I. deserved special financial terms. Despite the Confederation principle of representation by population in the eventual federal government, they also insisted that their people must have extra representation in the Commons: six seats instead of the five to which its population entitled it.

And the land question would not go away. In 1864 a new force, the Tenant League, launched a rent strike against the landlords and began organizing angry farm families into crowds that forcibly prevented bailiffs from collecting rents or seizing farms for non-payment. George Coles supported the league’s aspirations, but, as a law-abiding public figure, he shrank from endorsing its methods. The Tenant League could not break the landocracy, though its popularity among the tenants convinced a few landlords to start selling their land. Yet the passions that fuelled the Tenant League agitation showed that, if Confederation had no solution to offer on the vital issue with which the island had struggled for decades, it was not going to win hearts and minds among local voters.

Even when New Brunswick and Nova Scotia committed themselves to Confederation, Islanders remained opposed. Confederation’s advocates in the other British North American colonies that were involved in the negotiations began to regret Prince Edward Island’s absence and improved the terms they offered, but to no avail. In 1866 the P.E.I. legislature, led by Premier James Pope, declared there were “no terms” under which Prince Edward Island would become part of Canada.

In the summer of 1867, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick united with the Province of Canada to form the new Dominion of Canada. Prince Edward Island was out. (So was Newfoundland, which had its own reasons to be skeptical of Confederation.) Meanwhile, George Coles, staunchly anti-Confederation, returned to the premier’s office for the third time. The island would resist Confederation for six more years.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Left to fend for itself outside of Confederation — and newly liable to Canadian tariffs when it traded with the provinces across Northumberland Strait — Prince Edward Island did not waver. Its government sought a trade treaty with the United States, offering American fishing fleets access to its coastal waters in exchange for trade preferences. This alarmed both the Canadians, who had their own trade issues to sort out with the Americans, and the British, who disapproved of an outpost of barely ninety thousand people acting so independently in world affairs. There were rumours that P.E.I. might be annexed to the United States. Some Confederation supporters even discussed whether Britain should simply impose Confederation on Prince Edward Island, like it or not.

By 1871, however, Islanders had something to talk about other than Confederation and the land question. The new topic was railroads. In 1864, when the other provinces had made co-operation on railroads one of their vital reasons for unity, Islanders had been dismissive. Why should they pay taxes to support the Intercolonial Railway that would bind Ontario and Quebec to New Brunswick and Nova Scotia but do nothing for them?

But by the 1870s railroads had become an irresistible force, transporting goods and people throughout North America. Any community that still depended on dirt roads and horse-and-buggy transport would be a backwater, its agriculture and industry doomed to inefficiency. “No country could possibly keep pace with the times without her railways,” declared James Pope, who by then had been returned to the premier’s office. Every member of the island’s legislature was demanding either part of the main line or a branch line for his constituency. So universal was agreement on the need for a railroad that Premier Pope’s government signed the building contracts without even holding an election. As Prince Edward Islanders eagerly jumped aboard, the railroad carried them — faster than a speeding locomotive — straight toward Confederation.

Construction began in 1871. But the cost! Even before the line was complete, citizens suddenly faced the grim fact that the railroad was just too expensive for them to afford. The railroad was going to overwhelm the island’s budget and create an unsupportable tax burden. With the money already committed, there was no choice: Premier Pope had to renew talks with Canada.

Even under the threat of bankruptcy, the island drove a hard bargain. Political leaders fought over who could bargain hardest and who could seal the best deal. Since Canada was eager to add another province to Confederation, the Islanders did well in the negotiations. Canada took over the railroad and its debt burden. In defiance of the principle of representation by population, the island got its extra seat in the House of Commons. It got a promise of year-round ferry communication with the mainland, and Canada agreed to fund such basic provincial responsibilities as the law courts of the province. Even the land question would be solved. Canada agreed to loan the new province $800,000, the equivalent of tens of millions of dollars today, to buy out the landlords. At last the deal was done: Prince Edward Island became the seventh province of Canada one hundred and fifty years ago, on July 1, 1873.

1875 the provincial government passed the Land Purchase Act, which mandated the compulsory sale to the province of all estates over five hundred acres (about two hundred hectares), at a price set by the Land Purchase Commission. Two big landlords sued, but the Supreme Court of Canada rejected their claims, declaring that if the land issue remained unsettled it would “affect the peace as well as the prosperity of the Island.” By 1880 the province had used Canada’s loan to purchase more than eight hundred thousand acres (about three hundred and fifty thousand hectares) of land, reselling most of it to its former tenants and holding the rest to build up a reserve of Crown land for future development.

When Governor General Dufferin visited the province in 1873, he observed that Islanders were “quite under the impression that it is the Dominion that has been annexed to Prince Edward Island, and in alluding to the subject I have adopted the same tone.” Dufferin himself was a great landlord, supported by thousands of poor tenant farmers in Ireland. He did not much like the expropriation of his fellow landlords. But, on the land question, the British government would not interfere with a Canadian decision the way it had previously interfered with the island’s efforts to solve the problem.

Advertisement

Island patriots, including some fine historians, have sometimes suggested that the iron horse was a Trojan horse. As premier in 1866, James Pope, who later launched the railroad project, had campaigned against Confederation. He had even introduced the “no terms” resolution. But his brother William Pope had been the island’s strongest advocate for Confederation. After P.E.I. joined Canada, James Pope was accused of having opposed Confederation only to get elected, while secretly being in favour of it all along. For a hundred and fifty years, P.E.I. patriots have suspected that Pope offered people a railroad simply to trick them into Confederation. Had the island really made a free and informed choice?

But the forces confronting Prince Edward Island in 1873 suggest persuasively why Confederation had become the right choice. Within Canada, Prince Edward Island’s two pressing problems withered away: With its much larger population and greater resources, Canada took care of both the railroad debt crisis and the landlords. Within a few years of Confederation, at a comparatively small cost to the federal treasury, the farmers of Prince Edward Island were owners of their own properties. And the railroad, solvent again thanks to federal support, made itself central to island life for generations. It ran from Tignish in the northwest to Elmira in the east and was said to have one station for every four kilometres of track. For generations, much of the province’s produce was shipped to market via the train ferry at Borden. Highways gradually replaced rail, however, and the Prince Edward Island railway finally closed in 1989. The tracks are gone now, but the Confederation Trail on its right-of-way provides a beautiful route for hikers and cyclists.

George Coles did not participate in the island’s decision for Confederation. He did not even get to declare whether he would have supported it in the changed circumstances of the 1870s. A year into his third term of office that began in 1867, Coles started to suffer from a devastating mental illness. Soon he was compelled to retire from the premiership, and then from both politics and business. Guardians appointed by the courts had to sell his businesses to support the Coles family, and eventually he was confined, first to his own home and then to two successive asylums, one in Charlottetown, the other in New Brunswick. “Deserted by God and man, the miserable and unfortunate Hon. George Coles,” he described himself in a note scribbled down in the year his province joined Confederation, when he lay locked in a bedroom in his own home. He died two years later, in 1875.

Today George Coles is remembered as Prince Edward Island’s first premier and one of its most effective. His home, Old Stone Farm, is preserved, and in central Charlottetown an imposing public building, the George Coles Building, bears his name. In recent years, while Charlottetown’s Province House has been closed for renovations, this building — named to honour an anti-Confederation statesman who was a great Prince Edward Islander — has housed the provincial legislature as well as federal-government offices.

Prince Edward Island remains the smallest province of Canada in both size and population, though its 174,000 people make it the most densely populated province. It continues to benefit from federal investment and support and to contribute everything from potatoes to musicians to Canada and the world. In recent years immigration has diversified the population, and both Acadians and the First Nations have become well organized and visible. Fears of the island’s culture being extinguished by Confederation and of citizens being dispossessed of a voice in their own affairs have never been fulfilled. It’s the promise of the island’s unique attractions and its cultural distinctiveness, after all, that draws millions of us from across Canada and around the world to visit Prince Edward Island.

Crossing the Strait

Ice Boats

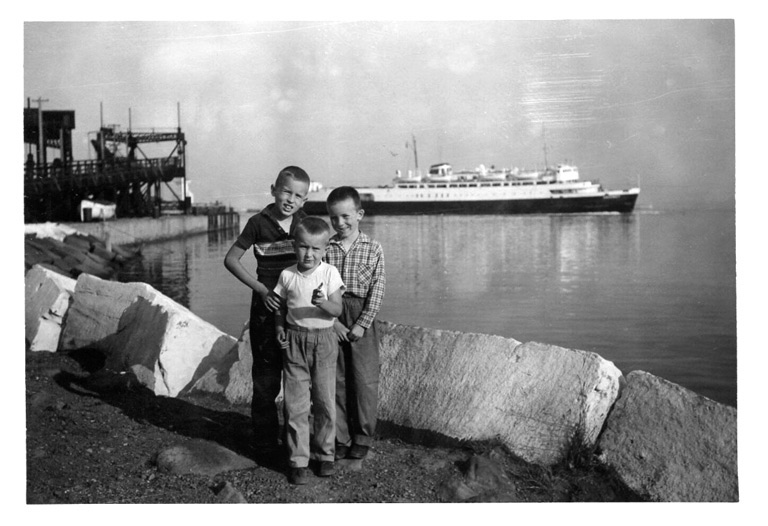

During the nineteenth century, small boats fitted with runners to travel over ice transported mail and passengers across the Northumberland Strait from P.E.I. to New Brunswick. Under the terms of P.E.I.’s entry into Confederation, the federal government promised efficient, year-round transportation of goods and people to and from the island. However, this didn’t happen until the advent of ice-breaking ferries in the early twentieth century. Watch a 1-minute video about Ice Boats

Ferry

Ferry service started in 1917, when SS Prince Edward Island began crossing from Port Borden, P.E.I., to Cape Tormentine, New Brunswick. The icebreaker carried railway cars, cargo, automobiles, and pedestrians. In 1941, a second ferry was added between Wood Islands, P.E.I., and Pictou, Nova Scotia. The ferry to Nova Scotia continues to run seasonally from May to December. Watch a 1-minute video about ferries propelled by horses

Confederation Bridge

The Confederation Bridge opened on May 31, 1997, replacing the ferry between P.E.I. and New Brunswick. Spanning 12.9 kilometres, it is the world’s longest bridge over ice-covered water. Although debate over social and environmental effects surrounded its construction, 59.5 per cent of Islanders voted in favour of the bridge, and about six thousand cars cross it daily.

We hope you will help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement