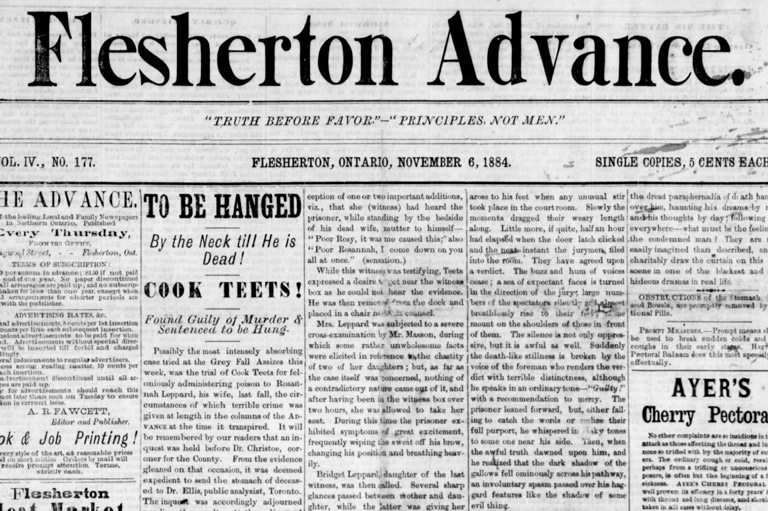

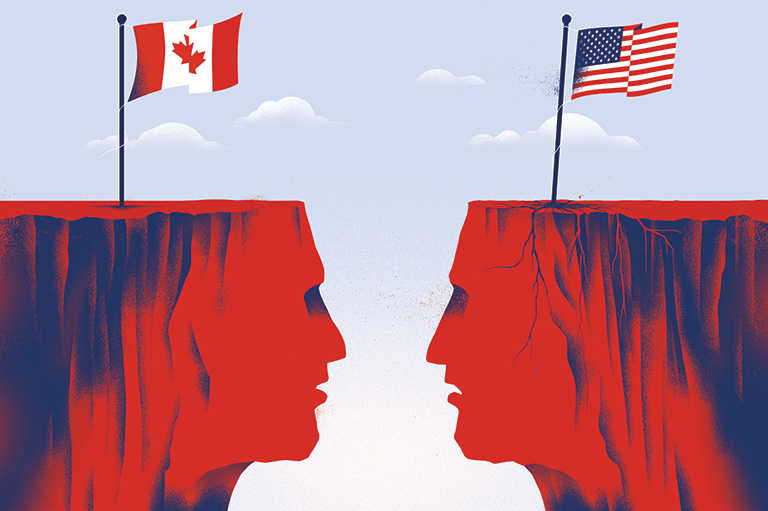

Friend or Foe?

“The Unanimous Voice of the Continent is Canada must be ours, Quebec must be taken.”

So declared John Adams, a future American founding father, in a February 1776 letter to James Warren, a fellow rebel from Massachusetts. At the time, an army from the American colonies occupied Montreal and Trois-Rivières and was laying siege to Quebec City. If they captured Quebec City, the seat of power in what was then a British colony, the rebels would be well on their way to satisfying a desire that the English in the Thirteen Colonies had held since their forebears first set foot in North America — control of the continent.

Adams did not realize when he wrote his letter that the nascent American republic’s attempt to liberate Canada from Britain was already all but lost. A desperate attack on Quebec City during a snowstorm on December 31, 1775, had failed miserably. The senior rebel general, Richard Montgomery, was mown down by grapeshot, causing his men to flee. His second-in-command, Benedict Arnold, was wounded while leading a separate attack. More than 300 of Arnold’s men were captured by the defending force of British regulars and French and English Canadians. The remaining American troops, poorly clothed for the harsh northern winter and riven with smallpox, held out until spring. The appearance on May 6 of British warships on the St. Lawrence River sent them scurrying for home, leaving food, weapons and wounded comrades behind.

It was not the first time, nor the last, that residents of the Thirteen Colonies sought to conquer Canada, a vaguely defined territory that first appeared on European maps in the mid-1500s. Its borders expanded and contracted depending on who was drawing the map and when, but the central core remained the area along the St. Lawrence River between Quebec City and Montreal.

Ever since France had begun sending colonists to Canada in the early 1600s to build New France, those colonists had come into conflict with the English settlers of the Thirteen Colonies — now the American eastern seaboard states of New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Two centuries of bloody warfare, of attack and counterattack, of burned settlements and slaughtered settlers ensued, continuing — after a slight pause — even after Canada passed from France to Britain in 1763. Both sides enlisted the First Nations as allies, exploiting pre-existing rivalries and creating new ones. The fighting finally ground to a halt after the War of 1812, leaving the two sides wary of each other. Planning for another American invasion continued on both sides of the border right up to the eve of the Second World War.

Canadians who have grown used to the relative calm of bilateral relations since then might be surprised by this history of antagonism. Several generations of politicians have assured us the Americans are our greatest friends and allies and reminded us that the two countries share the longest undefended border in the world. Lulled by this refrain, Canadians have been able to ignore the existential threat of living beside the more populous, powerful and periodically expansionist United States. The repeated threats by U.S. President Donald Trump to make Canada the 51st state brought this collective delusion to an abrupt end.

To prepare for an uncertain future, Canadians should look at past efforts by our southern neighbours to conquer Canada. There are lessons to be learned. Serious attempts fall into three overlapping categories: those inspired by global imperial rivalries; those motivated by the English colonists’ desire for more territory; and those where American leaders wanted to pursue what they regarded as their manifest destiny to occupy the continent and control the hemisphere.

In the earliest attacks, taking territory in North America was part of a larger, global conflict involving multiple players and places. European inhabitants generally identified as either English or French and followed the lead set in London or Versailles. If England and France were at war, so too were their colonists in North America.

The first recorded strike against French colonists occured in 1613, when a ship from the English colony of Virginia fired on a small group of men trying to build a settlement at St. Sauveur in what is now Maine. Each group brandished a royal charter from its respective king to back their conflicting claims to what were Indigenous lands. Neither recognized the legitimacy of the other’s claim. The Virginians captured the French, but eventually let them go with a warning that the entire East Coast, with its rich fisheries and fur trade, belonged to the English king.

The French regime in Canada could have ended in 1629 when an expedition led by British privateers David, Lewis and Thomas Kirke captured Quebec City and its founder, Samuel de Champlain. But King Charles I of England was in financial difficulties. The King decided in 1632 to hand back the captured territory in exchange for the second half of the dowry that the French King Louis XIII had promised when Charles wed his sister, Princess Henrietta Maria.

Determined assaults followed in 1690 and 1711, largely driven by English colonists who had grown weary of the brutal and bloody raids on frontier settlements in New York and Massachusetts by the French and their First Nations allies. William Phips, a future governor of the colony of Massachusetts Bay, sailed up the St. Lawrence River in 1690 intent on taking Quebec City. With him were 2,000 Massachusetts militia. He failed, but managed to capture Port Royal, a French settlement on the Bay of Fundy. A far larger operation in 1711, involving an estimated 4,000 British soldiers, sailors and colonial militia, ended in disaster when a storm drove the ships onto the rocks near Anticosti Island in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, killing more than 800. The English admiral of the fleet called off the attack and sailed for home.

English colonists registered a partial success in 1745, when a combined force of about 4,000 men from Connecticut, Massachusetts and New Hampshire took the French Fortress of Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island. Louisbourg was an important prize. It sat at the mouth of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, guarding the gateway to Canada, which would have been the next target. William Shirley, the governor of Massachusetts, had told his superiors in London that “reducing,” or capturing, Louisbourg would cut off French navigation to Canada and “would probably in a little time be attended with an easy Reduction of that Country.” Capturing Canada, said Shirley, “would give his Majesty’s subjects the whole Furr Trade, now chiefly in the possession of the French of Canada, and render ’em Masters of an entire Territory of about eighteen hundred miles extent upon the Sea Coast (reckoning from Georgia to Newfoundland inclusive).” He had to put his dream on hold when Britain handed Louisbourg back to France in a 1748 peace treaty.

The final act in the imperial struggle over Canada came during the Seven Years’ War, a global conflict involving five European countries and their overseas colonies. In 1760, a British-colonial force captured Montreal, making the demise of New France all but inevitable. Quebec City had fallen the year before at the famous Battle of the Plains of Abraham. At the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1763, France left North America with some relief. Its chief negotiator, Étienne François, duc de Choiseul, told Britain from the start of the peace talks it could have Canada — France preferred to keep the sugar-rich Caribbean island of Guadeloupe. Official France agreed with the writer Voltaire’s assessment that the northern colony was nothing more than “quelques arpents de neige” — a few acres of snow.

Advertisement

American happiness at having Canada as a fellow British colony was short-lived. The Quebec Act of 1774 made it clear that the conquered French territory would not resemble the Thirteen Colonies. It would retain its own religion and laws, as well as borders that replicated those of the French regime, when New France extended along the St. Lawrence River valley and included the land surrounding the Great Lakes.

Tolerating the practice of Catholicism was anathema to the largely Protestant English colonists. “Does not your blood run cold, to think that an English parliament should pass an act for the establishment of arbitrary power and popery in such an extensive country?” asked the young revolutionary Alexander Hamilton in A Full Vindication of the Measures of Congress, his 1774 pamphlet protesting British measures. They also found it hard to understand why French Canadians did not see the value in their governance and legal systems, including trial by jury and habeas corpus, meant to prevent illegal detention. The American desire that everyone copy their systems has deep roots.

But what really riled the land speculators and aspiring settlers was that Britain wanted the Thirteen Colonies restricted to the territory between the Atlantic Ocean and the Appalachian Mountains. Prior to the British conquest, the colonists had fought the French for the contested territory west of the Appalachians. Now, it seemed they would have to fight Britain. They added this to their growing list of grievances with the British government that would eventually spark their revolution.

In 1774, following the Quebec Act, delegates to a congress in Philadelphia issued a ham-fisted invitation to “the inhabitants of the Province of Quebec” to join them in their struggle against the British government. The invitation was part of a lengthy screed on the rights to which French Canadians were entitled as “English freemen” — rights they would obtain if they joined the American fight against the British government. “You are a small people, compared to those who with open arms invite you into a fellowship,” the letter said. It suggested they reflect on whether they wanted “all the rest of North America your unalterable friends, or your inveterate enemies.” If they knew what was good for them, they would allow themselves to be “conquered into liberty.”

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

When French Canadians, who accounted for more than 95 per cent of Canada’s non-Indigenous population, did not respond to this and to subsequent invitations, the Americans decided to invade Canada in the late summer of 1775. The pretext was that Britain was preparing to launch an attack on the U.S. from the north, using the Canadians and their First Nations allies. Britain might well have liked to do so, but as Guy Carleton, the British governor of the Province of Quebec, confided to his London superiors in June, “We are equally unprepared for Attack or Defence; Not six hundred Rank & File fit for Duty upon the whole Extent of this great River, not an armed Vessel, no Place of Strength; the ancient Provincial Force enervated and broke to Pieces.”

The 1775-76 invasion failed because of poor intelligence; a lack of funds, food and equipment; the opposition of the French-Canadian clergy; and an outbreak of smallpox. Plans for a rematch during the American Revolution never made it beyond the drawing board because the Americans were preoccupied with fending off British attacks closer to home. The 1783 Treaty of Paris, which ended the revolution, acknowledged American independence. But it did not award Canada, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland or St. John Island (present-day P.E.I.) to the United States, despite a last-minute bid by American negotiator Benjamin Franklin for the British colonies. Part of the Canada-U.S. border that Trump wants to erase — the bit between the Atlantic Ocean and the western extremity of Lake Superior — was agreed upon by American negotiators Franklin, John Jay and John Adams, along with British negotiator David Hartley, at those peace talks.

Historians debate whether the War of 1812, which has achieved mythical status in Canada as a victory for the Canadian militia, was truly intended as a war of conquest. Alexander Smyth, one of the invading generals, seemed to think so when he told his troops they would be entering a country “that is to be one of the United States.” British diplomats negotiating the peace deal in Ghent in 1814 clearly agreed. “[I]t is notorious to the whole world that the conquest of Canada and its permanent annexation to the United States was the declared object of the American Government,” they wrote to their American counterparts.

Yet others think that the American leaders were simply trying to force Britain to stop snatching former British sailors off American ships, and to start vacating military posts on what was now American territory south of the Great Lakes.

In his book The Picky Eagle: How Democracy and Xenophobia Limited U.S. Territorial Expansion, historian Richard Maass argues that the United States did not want to annex Canada or Mexico because that would mean sharing self-government with an alien race that would “corrupt the United States rather than improve it.” Such annexations would also upset the precarious balance between northern states that were anti-slavery and the southern, pro-slavery states. There are echoes of his argument about maintaining balance in the more recent assertion that adding Canada to the American mix would benefit the Democratic Party. The 1814 peace treaty left the prewar borders in place.

“Had we not had the strong arm of England over us, we should not now have had a separate existence.”

— Thomas D’arcy Mcgee, 1865

Regardless of American intent, the 1812 invasion left Canadian political leaders with a lingering fear that it was just a matter of time before the Americans tried again. There were repeated scares in its aftermath. The rebellions in Upper and Lower Canada in 1837 and 1838 provided an opening for American leaders to exploit what some saw as growing republicanism in Canada. There were scattered attacks along the border by members of American secret societies called Hunters’ Lodges, but none had official U.S. government sanction. Ultimately, the rebellions failed.

On the West Coast, the dispute with Britain over the Oregon Territory — the area between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains stretching from Mexico’s northern border to Russian Alaska’s southern border — provided another opening. Britain and the United States had agreed in 1818 to extend the northern border of the U.S. westward along the 49th parallel from Lake of the Woods, in present-day Ontario, to the Rocky Mountains. Beyond the mountains, however, the frontier remained undefined. John O’Sullivan, a journalist and a fan of annexation, summed up the popular mood in the United States when he wrote in 1845 that Oregon was American “by right of our manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions.” Fortunately for Canada, the Americans were preoccupied during the 1840s with adding Texas, as well as the Mexican territories between Texas and the Pacific Ocean, to their union. Instead of going to war, they negotiated a division of the Oregon Territory with Britain in 1846, creating the border that exists today.

The American Civil War, particularly its aftermath, brought on a new bout of jitters. Would heavily armed and battle-hardened American troops head north? Canada had handed them the perfect pretext by turning a blind eye to Confederates taking refuge in the British colony and using it as a base to launch ill-fated attacks on the U.S., including one on St. Albans, Vt., in 1864. The Fenian Brotherhood — composed of Irish-American radicals who wanted to conquer Canada either to divert British troops and facilitate an Irish uprising, or to hold it hostage until Britain freed Ireland — were active in this period. While some American political leaders expressed sympathy for the Fenian cause, they were more preoccupied with the hard work of mending their broken union and purchasing Alaska from Russia in 1867. The U.S. government was also reluctant to provoke confrontation with Britain, which might endanger their trade relationship.

The Red River Resistance in 1869-70 led to calls in some northern states to annex the Red River Settlement at Fort Garry (later Winnipeg). The Minnesota legislature passed a resolution in March 1868 expressing its regret that the territory between Minnesota and Alaska — granted to the Hudson’s Bay Company by the British Crown in 1670 without the consent of its Indigenous inhabitants — was about to become part of the Dominion of Canada. The legislators said they would “rejoice” if instead it became part of the U.S. Two years later, Zachariah Chandler, a senator from Michigan, urged Congress to open negotiations with Winnipeg on annexation. Those calls came to naught.

The last time Canada actively prepared for a war with the United States was in 1895 when an obscure dispute over the border between Venezuela and British Guiana led American President Grover Cleveland to threaten war. Canada, whose foreign policy was still decided in Britain, was the closest target. The Canadian government quickly ordered from Britain 40,000 rifles, 2,300 carbines, 24 field guns and some Maxim machine guns for the militia. Both sides backed down before shots were fired.

Still, as late as the 1940s, some Canadian political leaders were convinced that the United States was just biding its time. Prime Minister Mackenzie King confided to a friend after the Second World War that the secret aim of every American leader including Franklin Roosevelt, who served as president from 1933 to 1945, was to dominate Canada and ultimately to possess the country. If true, Trump is not an aberration, but part of a long-term strand in American political thought.

Canada survived American threats and invasions for reasons that could not easily be replicated today, with the possible exception of internal division in the United States. Royal whim and the politics among the European colonial powers were important factors in the early days; much later, Britain’s presence in Canada likely dampened American urges to make a grab for the colony at opportune moments.

“They coveted Florida, and seized it; they coveted Louisiana, and purchased it; they coveted Texas, and stole it; and then they picked a fight with Mexico, which ended by their getting California,” the Irish-Canadian parliamentarian Thomas D’Arcy McGee told the House of Commons in 1865 during the pre-Confederation debates. “They sometimes pretend to despise these colonies as prizes beneath their ambition; but had we not had the strong arm of England over us, we should not now have had a separate existence.”

A report by Russian military strategists in 1887 looked at the Canadian Pacific Railway in terms of its capacity to move British troops to the Pacific to confront the Russians, even though most British forces had left Canada in 1871. Two reviews of the military situation along the Canada-U.S. border, written in 1888 and 1890 by American military officers, also factored in the participation of the British navy and other military forces in any future confrontation.

American distraction also helped Canada to survive, as other goals often took precedence. The Americans sent a weak, poorly equipped force to Canada in 1775-76 because they needed most of their troops, money and equipment to protect the Thirteen Colonies. In the 1840s, Texas, Mexico and California exerted a stronger pull on their expansionary instincts. It was not that American leaders did not want to add Canada to their union, they just wanted other things more.

Problems at home, both real and anticipated, likely forestalled some annexation plans, especially after the Civil War when adding Canada to the Union had the potential to upset the delicate balance between northern and southern states. And finally, there is a strain of thought in the United States that Canadians would eventually see the light and join them without having to be coerced. This “fruitdrop theory of empire” emerged as early as the 1850s, historian Reginald Stuart wrote in his book, United States Expansionism and British North America, 1775-1871. Its adherents believe time is on their side.

The most important of these factors, the British presence in Canada, no longer holds true. Canada’s connection with Britain has weakened to the point where it is unclear whether Britain would have our back if Trump decided to use military force. Canada’s best hope is that one of the many fires Trump has been lighting will burst into a conflagration that will command all his attention. There are many to choose from, including the undermining of the American economy with tariffs and tariff threats; the destabilization of Europe with his scorn for Ukraine and praise for Russian President Vladimir Putin; and the possible collapse of the American government following the chaotic cuts to funding and staff.

Fear of creating a domestic imbalance, not between states but between Republicans and Democrats, might also stay Trump’s hand. Or — and this is not to be wished for — he may decide to go after Greenland or the Panama Canal first.

There remains the possibility, however remote it may seem in early 2025, that the unpredictable president with imperial ambitions may decide that adding Canada to the United States will cement his place in history. He seems confident, despite all evidence to the contrary, that Canadians want to become Americans. So, too, were the congressional delegates when they launched their first invasion in 1775. The words of Adams, a firm backer of that attempt, might serve as a warning to the current president. “Alas Canada,” he lamented to a friend after the invasion failed in 1776. “We have found Misfortune and disgrace in that Quarter.”

Notable Events in Canada-U.S. Relations

1775

An American force tries, and fails, to take Quebec City as part of a plan to annex Canada.

1812-1815

The United States attacks Canada as part of the War of 1812, which ends in a stalemate.

1837 & 1838

Despite rebellions in Upper and Lower Canada, republicanism fails to take hold in British North America.

1869-1870

The Red River Resistance leads to calls in some northern states to annex the Red River Settlement.

1938

The Thousand Islands Bridge across the St. Lawrence River opens, linking Canada to the United States.

1965

The Canada-U.S. Auto Pact leads to the integration of the auto industries in a shared market.

1994

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) comes into effect.

2025

U.S. President Donald Trump voices his desire to make Canada the “51st state.”

In today’s environment of misinformation and disinformation, it can be hard to know who to believe. At Canada’s History, we tell the true stories of Canada’s diverse past, sharing voices that may have been excluded previously. We hope you will help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past, highlighting our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages – award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts. Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement