Finding Reconciliation

In 1857 the province of Canada enacted a new law it called the Gradual Civilization Act. Who could be against civilization? But the Gradual Civilization Act was not intended to encourage the arts or to raise the cultural level of backwoods settlers. It was aimed at the Indigenous peoples of the province. “Civilization” meant assimilation.

The new law authorized the government to declare any Indigenous man “enfranchised” if he were educated and could read and write. Enfranchisement provided the vote, and also a little money and a little land — both of which would come from the First Nations band of which he had formerly been a member.

Above all, enfranchisement meant that he and his spouse and children would no longer be “Indians.” They would cease to be part of any Indigenous band, tribe, or nation. Enough enfranchisements, and there would be no “Indians” — and no First Nations left in Canada.

The Gradual Civilization Act had a long life. In 1876, with more measures for coercion and control added to it — including compulsory residential schooling — it became Canada’s Indian Act. In the 1920s, the federal government planned further amendments. Duncan Campbell Scott, the deputy minister at the Indian Department, declared that the Indian Act’s “whole object” was that every Indigenous person would be “absorbed into the body politic” and cease to be an “Indian” under the law.

In North America, “civilization” projects of this kind have had an unbroken record of failure for about five hundred years. Indigenous scholars and leaders have long identified the Indian Act — and the Confederation-era political leaders who created it — as tools and agents of cultural genocide. In recent years, John A. Macdonald, Canada’s first prime minister and the most prominent political leader of that era — and the one honoured with the most statues — has been singled out for particular criticism on this issue.

It’s worth remembering that some parts of the Indian Act came from Conservative governments, others from Liberal governments. In the years around Confederation, all Canadian politicians and all political parties endorsed the forced assimilation of Indigenous peoples.

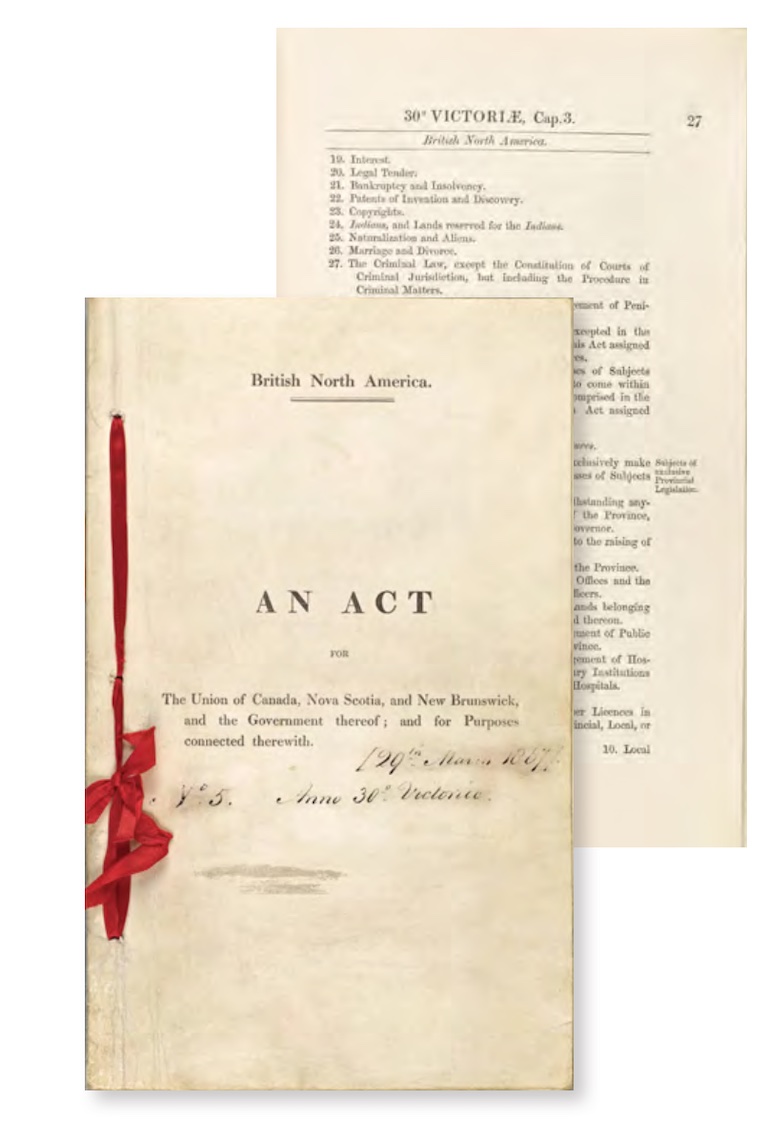

When they came to draft a constitution for Canada, however, that same generation of politicians, representing all parties, had endorsed an alternative model for relations between the Canadian state and the First Nations. When they made Confederation in 1867, the politicians who negotiated the terms of union put a Treaty-based relationship with First Nations permanently into Canada’s Constitution.

It is important for the future well-being of Native-newcomer relations, treaty implementation, and the social cohesion of Canada that everyone come to recognize that “we are all treaty people.” — J.R. Miller, Compact, Contract, Covenant

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

THE TREATY RELATIONSHIP

No one from the First Nations participated in framing the British North America Act of 1867, and there is only a single line about Indigenous peoples in it. That one line, however, made “Indians and lands reserved for Indians” a federal responsibility, and therefore embedded the Treaty-making obligation in Canada’s constitution.

Unlike the Indian Act, which was created and administered by the Canadian government alone, Treaties were agreements between two parties — Canada and the First Nations. Where the Indian Act offered only coercion, the Treaty process promised, at least in theory, a relationship between equals.

Treaty-based relationships are older than the British North America Act or the Indian Act, even older than British North America. Indigenous nations of North America had negotiated Treaties among themselves before Europeans ever reached the Americas. French, British, and Dutch colonizers all made Treaties with the First Nations — for trade, for military alliances, for the use of land.

When the British government displaced France in North America, it needed to build alliances with First Nations who had long been allies of New France. To hasten that process, Britain declared, in the Royal Proclamation of 1763, that land belonging to Indigenous nations of North America could never pass into the possession of British subjects except through Treaties between the Crown and the First Nations. Such Treaties had to be negotiated “at some public meeting or assembly of the said Indians to be held for that purpose by the governor or commander-in-chief of our colony.” The Crown was acknowledging that First Nations were self-governing powers holding territory and able to enter freely into this kind of diplomacy.

In 1764, many First Nations — old allies as well as former enemies of the British — gathered at Niagara in present-day Ontario and ratified a new alliance with the British Crown. The symbol of the Treaty of Niagara was the Two-Row Wampum, a traditional piece of beaded artwork that expressed the essence of the agreement. On the Two-Row Wampum, the allies — both newcomers and Indigenous peoples — were depicted as two canoes travelling in tandem along separate, parallel streams. That image — First Nations and colonial powers as independent allies bound by Treaty — was the tradition that was constitutionalized in the British North America Act’s brief reference to Indigenous peoples and their land. It bound the new federal government to negotiate with independent First Nations on land questions.

From Confederation, a fundamental tension existed in Canadian law and policy on Indigenous matters: on one hand, the coercive, assimilative program driven by the Indian Act and, on the other, the Treaty-based relationship with self-governing equals. That is the conflict with which Canada still struggles.

At least, it is a conflict if Treaties matter. But, from the time the Canadian government started making Treaties, it had another word for them: “surrenders.” Ottawa interpreted its Treaties to mean that, through them, First Nations’ land ownership was “extinguished.” In the Canadian government’s view, most of the work of a Treaty was done the moment it was signed, for it documented not a relationship but only a permanent transfer of authority. The numbered Treaties made by the new government of Canada, starting in 1871, cover territory from Hudson Bay to the Rockies and up to the Arctic. The printed text of each Treaty included a blunt declaration that the involved bands and tribes would “cede, yield, release, and surrender” their land to the Crown and to Canada.

For most of a hundred years from the 1870s, Canada’s assertion that Treaties were surrenders, in which Indigenous title was extinguished and the land became Canada’s to use as it pleased, meant that the Treaty process reinforced the Indian Act. “They have operated in tandem,” Hayden King of the Yellowhead Institute, an Indigenous research centre at Toronto’s Ryerson University, told me in 2020. “Look at the numbered Treaties of the Confederation era. The most draconian elements of the Indian Act were developed precisely in tandem with the Treaties of 1876 to 1920: the confinement to reserves, the economic harassment, the removal of children. I can’t help but think they were dual sides of the same process.” By 1927 the Indian Act even forbade Indian bands from hiring lawyers to assert their Treaty rights, a rule that lasted twenty-five years.

A NEW SENSE OF TREATY MAKING

Ever since the first Treaties were made, Indigenous leaders have insisted that the words in the printed texts do not tell the truth of the Treaties. They have asserted that the actual Treaty negotiations — at the “public meeting or assembly of the said Indians,” as required by the royal proclamation — were not land sales but genuine agreements about mutual assistance and about how First Nations and newcomers could share the land and its resources.

When I spoke in 2011 with Stan Louttit, then the grand chief of the Mushkegowuk Cree of northern Ontario, he knew why his grandfather had put his mark on the James Bay Treaty early in the twentieth century. “They were poor,” he said simply. By agreeing to share the resources of their land with Canada, they calculated that they might gain tools, and education, and medicine as well as protection from unregulated incursions by outsiders. But sharing was not surrender.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Early this year, Harold Johnson, a Cree writer and lawyer in La Ronge, Saskatchewan, told me how his great-grandfather observed the negotiation of Treaty 6 and understood that it meant “your family came here and asked to live with us on our territory and we agreed. We adopted you in a ceremony that your family and mine call a Treaty.”

John Borrows is Anishinaabe/Ojibway and a member of the Chippewas of the Nawash First Nation in Ontario as well as the Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Law at the University of Victoria.

He described how his great-grandfather helped to make a Treaty that covers six hundred thousand hectares in what is now southern Ontario: “He understood it as an invitation for settlers to come and live among us. I believe he understood the people would live peacefully and would share ideas — religious, economic, all kinds — and that the settlers would also learn and understand our laws about how to live.”

None among these Indigenous leaders, writers, and scholars believes that their ancestors “surrendered” their people’s homeland or agreed to the “extinguishment” of their rights. They never heard those words at the Treaty talks. But the Canadian government’s version of Treaty making as surrenders and extinguishments dominated the legal and historical record for a long time. In the century-long heyday of the Indian Act, Indigenous understandings of the Treaty process were derided and dismissed by governments, by courts, and by historians. An Ontario judge, William Riddell, declared in 1921 that, on this matter, “there are no troublesome subtleties in Canadian law.”

THE RETURN OF TREATIES

Since the 1970s, Indigenous advocacy for a different understanding of rights and Treaties has begun to make headway. In that decade, the Nisga’a of British Columbia and the Cree of Quebec convinced the Supreme Court of Canada to make landmark rulings confirming that Indigenous title was a legal reality.

In the last fifty years, Canadian courts have begun to rule that Treaties remain in force and have to be respected. In a 1990 judgment called the Sioui case, the Supreme Court declared that the Crown must interpret Treaties not for its own convenience but “in the sense in which they would naturally be understood by Indians.”

As Canada’s courts revived Treaty law, Canadian historians — both Indigenous and non-Indigenous — began to provide scholarly support for the long-standing Indigenous understanding of the Treaty relationship.

As historians looked more closely, they learned that First Nations often initiated Treaty making and were seeking aid such as agricultural assistance, territorial protection, and education. They employed traditional rituals of Treaty making and bargained hard for their interests. “We have a rich country; it is the Great Spirit who gave us this,” said Mawedopenais, one of the Ojibwa negotiators of Treaty 3 in 1873. “Where we stand upon is the Indians’ property.” Historical records confirmed the oral evidence: Canada’s Treaty commissioners were consistently obliged to make verbal commitments that the land was to remain with its people.

In 1899, when Treaty 8 was being made on the northern prairies, the chiefs declared their people unwilling to be cooped up on reserves, since this meant they would be unable to follow their seasonal rounds. The Treaty commissioners had to assure them “that the Treaty would not lead to any forced interference with their mode of life.”

In 1905, negotiating Treaty 9 in northern Ontario, commissioner Duncan Campbell Scott had to declare that reserves could never limit the people’s movements — they were only places where no white man could trouble them.

As to their concerns about losing their lands, he assured them, “The land will always be yours. You may hunt and fish forever.” On such assurances, chiefs put their marks on Treaty documents that were already printed with an entirely different set of understandings, including words like “surrender” and “extinguish.”

Summed up in studies like Canada’s First Nations (1992), by Métis historian Olive Dickason, and Compact, Contract, Covenant: Aboriginal Treaty Making in Canada (2009), by historian J.R. “Jim” Miller of the University of Saskatchewan, historians of the Treaty relationship began to express a new consensus that is one of the great achievements of recent Canadian historical scholarship.

As the subtitle of John Long’s history Treaty No. 9: Making the Agreement to Share the Land in Far Northern Ontario in 1905 (2010) declares, Treaties as negotiated were not surrenders but “agreements to share the land.”

A PATH TO RECONCILIATION?

Can a Treaty-based relationship, an agreement to share, now replace the coercive Indian Act as the basis of dealings between First Nations and Canada? Few non-Indigenous Canadians may have deeply considered the implications of “sharing the land,” but guidelines do exist in commission reports, legal studies, and proposals for discussion. For First Nations leaders, at least, the basic principles are clear.

The late Arthur Manuel of British Columbia’s Secwepemc Nation, sometimes called the “Nelson Mandela of Indigenous peoples” for his global perspective on rights issues, saw two clear requirements. The first was the recognition of First Nations governments “with powers and jurisdiction appropriate to a distinct order of government within the Canadian federation.” The second was a secure economic base, grounded in sharing the land and its resources, to make these Indigenous governments viable and self-supporting, not simply dependent on funds from Ottawa. (Manuel did not argue that First Nations should have these rights. He insisted that they already have them and that these rights are guaranteed by Treaties, by the Canadian Constitution, and by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.)

“Say we use the Treaty as the framework,” the Yellowhead Institute’s Hayden King said. “Look at Crown land in Ontario, for instance. Let us share jurisdiction, share resources, share revenues from that territory. All communities would have to be engaged. They would reach agreement on how to share: moose hides, gold mines, water, power resources. At the same time, we would also be better able to honour our obligation to the land, to the animals. That would be one manifestation of getting back to the Treaty relationship.”

Early in 2020, the crisis over the pipeline being constructed across Wet’suwet’en territory in British Columbia demonstrated how difficult the sharing concept remains for governments and corporations, and probably for most Canadians. Few denied the enduring Wet’suwet’en title to the land the pipeline being constructed would cross — there is no Treaty there — yet many Canadians seemed unable to conceive of a Wet’suwet’en right to say no to a megaproject endorsed by non-Indigenous governments.

Yet a relationship based on the Indian Act, where a cabinet minister in Ottawa must play the role of police chief, health and welfare director, school board chair, and development officer for every reserve community in Canada, offers no workable future. In recent years, Attawapiskat in northern Ontario’s Treaty 9 territory has become notorious as one of the country’s poorest and most deprived communities. Yet Attawapiskat has diamonds, among other resources, practically in its backyard, on land Ontario considers surrendered. Peoples who own and control diamonds are rarely poor. If we acknowledged Treaty 9 as an agreement to share the land, not as a surrender of it, a Treaty share of such resources could make the Cree and Ojibwa of Treaty 9, and other First Nations across Canada prosperous and secure, able to run their own schools, clinics, and police departments by their own policies and revenues.

Few enough Canadians are yet ready to concede the existence of an Indigenous right to share the Canadian land and to draw from it revenues that could secure and support a prosperous independence within the Canadian federation. Perhaps no Canadian government could yet propose such an agreement and survive future elections. Yet reconciliation depends on it.

Reconciliation based on sharing is what is proposed by the Treaty relationships that have endured through centuries of contact. The relationship based on the Indian Act has been a failure for a century and a half. The First Nations — and most of our historians, too — see a better future in the other, older way, the Treaty relationship that was embedded in the Canadian Constitution a century and a half ago.

Canada's History magazine was established in 1920 as The Beaver, a Journal of Progress. In its early years, the magazine focused on Canada's fur trade and life in Northern Canada. While Indigenous people were pictured in the magazine, they were rarely identified, and their stories were told by settlers. Today, Canada's History is raising the voices of First Nations, Métis and Inuit by sharing the stories of their past in their own words.

If you believe that stories of Canada’s Indigenous history should be more widely known, help us do more. Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share Indigenous stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement