A Father’s Grief

On September 13th 1918, Captain Robert Bartholomew suffered a sudden nervous breakdown after reading his son’s name in a newspaper casualty list. His only child, nineteen-year old Private Verne Lyle Bartholomew, had been killed in action at Hangard Wood on August 8th 1918. Unable to carry on with his administrative duties in England, the elder Bartholomew fell into a malaise and was hospitalized with neurasthenia one month later. A medical board recorded, “He is suffering from severe depression following the mental shock of the news.”1

Although many historical studies of the First World War have detailed the psychological stress and trauma endured by frontline soldiers, more research is also needed into the mental and emotional effect of the war on those on the home front in England and Canada. To what extent did deaths of sons shape the ways in which the older generation of fathers interpreted the conflict? How did these reactions affect notions of masculinity, duty and patriotism for men too old to see active service themselves? For fathers who had enthusiastically championed the war, the death of a son exposed an underlying tension between public rhetoric and private grief.

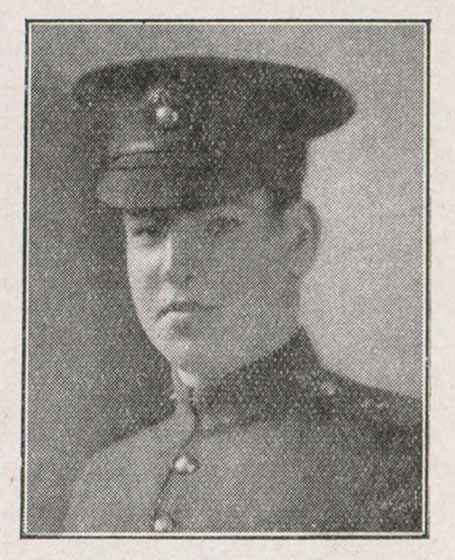

Robert Bartholomew was a forty-seven year old editor of the Conservative Cookshire Chronicle when he enlisted with the 117th (Eastern Townships) Battalion as paymaster in December 1915. The Quebec-born widower’s son had already enlisted, and transferred into his father’s unit. After the breakup of the battalion in England in early 1917, father and son were separated; the former joined the Canadian Army Pay Corps in England while the latter went to the 14th Battalion in France. Due to his newspaper publishing experience in civilian life, the elder Bartholomew became editor of the Canadian Hospital News magazine in May 1917. In each weekly issue, Cpt. Bartholomew’s editorial commentary usually interpreted the war as a defence of civilization against Germany, “the most hypocritical and brutal monster known to history.”2

In the Christmas 1917 edition of the Hospital News, Bartholomew explained that fathers and mothers of dead soldiers, “notwithstanding their sorrow and pain, will be able to look back with a feeling of pride and say: ‘They died for God, for King and Country.’”3 Seven months later, Bartholomew’s views were tested when he learned his own teenaged boy was now “sleeping beneath the soil of France.” 4 On reading the death notice, Bartholomew collapsed. Doctors later attributed the debilitating shock to continuous overwork over the course of two years. Many of his symptoms including, “loss of concentration, loss of memory, general nervousness and marked depression,” paralleled the symptoms of shell-shocked soldiers on the front.5

One week later, the September 21st Hospital News editorial, entitled “When the News Comes,” considered the emotional toll military death notices had on families at home. Despite “continually trying to school ourselves in order to be prepared to meet the worst,” the writer admitted, “It gives us such a shock that we can scarcely realize it in time.” Written either by Bartholomew himself or, given his shaken state, by his new assistant editor Corporal T. W. McCafferty, the article nevertheless reassured readers that the deaths had not been in vain. The editorial quickly shifted away from pessimism to strike a jingoistic tone. It declared Canada’s “sons have died by thousands and will continue to die by thousands if necessary, until victory is assured.” The writer called for not just the conquest of Germany but also for total retribution against the “hordes of savages.”6

In contrast to the patriotic certainty contained in the editorial, medical reports of Bartholomew’s condition depicted a shattered man. Doctors noted, “He is very uncertain of his actions, wandering about from place to place with no particular object in view and forgetting what he started to do.”7 Months earlier, as the Hospital News editor, Bartholomew had emphasized the crucial importance of relentless cheerfulness to winning the war, writing, “we must bury our individual troubles and keep smiling all the time.”8 “In other editions, he had called on readers not to be pessimistic lest they discourage those whose “nerves strained to the highest tension” were awaiting news from a family member in uniform.9 Unable to live up to his own optimistic, cheerful ideal in the wake of his son’s death, Bartholomew was admitted to the Granville Canadian Special Hospital at Buxton on October 10th 1918. Two weeks later, the Canadian Hospital News ceased publication. The final edition summed up the fate of the magazine “in three words, ‘Killed in Action.’”10 Invalided to Canada after the armistice, Bartholomew continued to be treated in hospital until 1920. His emotional suffering had also produced physical ailments and bodily pains.

The experience of Captain Bartholomew illustrates the conflicted feelings of a father struggling to find meaning in a war that cost him his only son. As the Hospital News editor, Bartholomew articulated the popular mythology of the war as a noble crusade, and prescribed the appropriate behaviour and temperament for men on the home front and behind the lines. Supporting the war effort was the priority. Fathers needed to project enthusiasm and cheerfulness despite anxiety or personal tragedy. But when confronted with the loss of his son, Bartholomew fell into depression and indicated the fragility of this type of patriotic and masculine rhetoric. What comfort Bartholomew drew from the slogan, “They died for God, for King and Country” is unknown, but his nervous breakdown suggests that genuine patriotic zeal was no match for the profundity of personal loss.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement