Patriotes Down Under

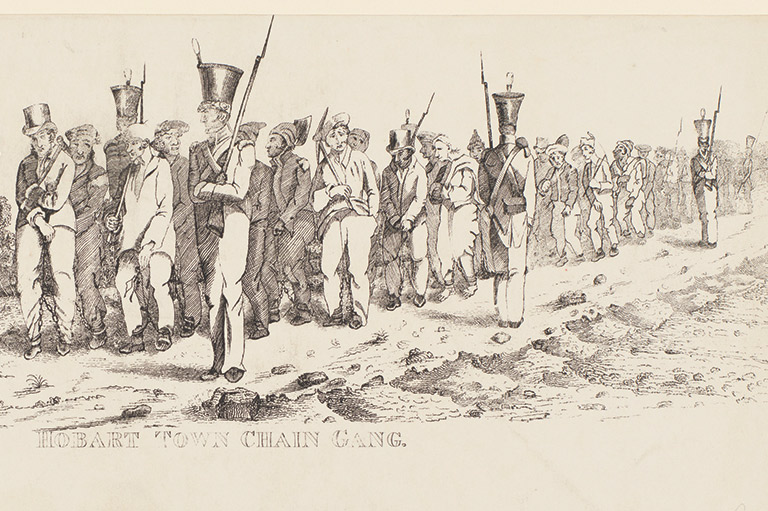

In February 26,1840, Louis-Léandre Ducharme stood on the deck of the sailing ship HMS Buffalo and gazed at a gang of prisoners working onshore. “Looking down from the deck we saw miserable wretches harnessed to carts, engaged in dragging blocks of stone for some Public Buildings; others were unloading them,” he wrote in his memoirs. “The sight of this brought us many sad thoughts, for we believed that within a few days we, too, would be employed exactly as they were.”

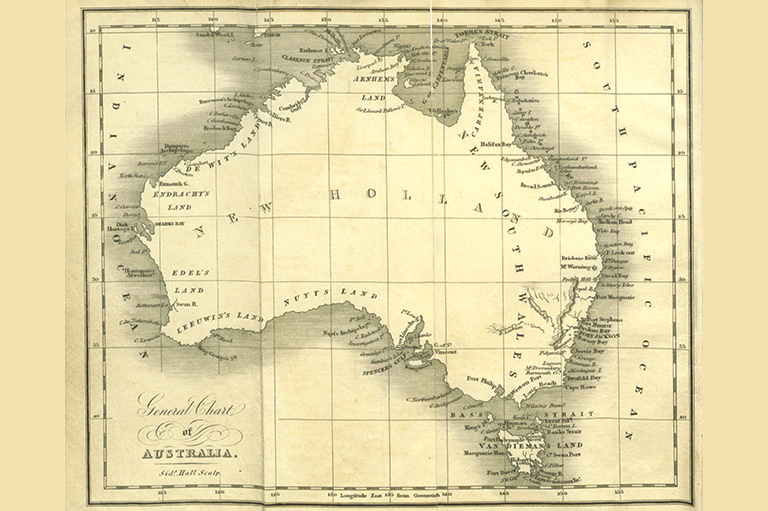

Ducharme and his fifty-seven shipmates had just arrived at Port Jackson in Sydney, New South Wales, after enduring a five-month voyage from Montreal to this far-flung penal colony on the Australian continent. Although they were prisoners, Ducharme and his companions were no common criminals. They were Patriotes — Lower Canadian revolutionaries who had taken up arms to fight for democracy against autocratic British colonial rule.

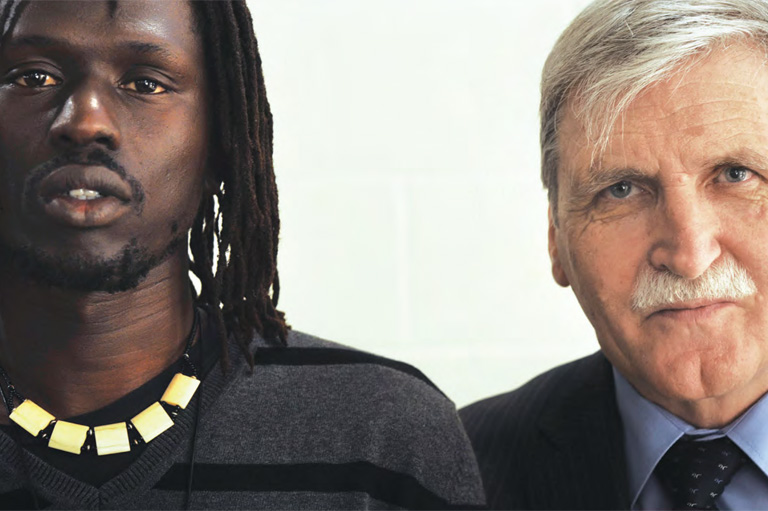

Then as today, the Patriotes were widely revered as heroes in their homeland. Although they did not gain the same recognition elsewhere, their actions had consequences that extended far beyond Canada. “By the sacrifices they made by fighting bravely for their ideals, these French-Canadian Patriotes … helped build responsible government and democracy both in Canada and Australia,” Australian historian Tony Moore, author of Death or Liberty: Rebel Exiles in Australia 1788–1868, said in an interview. “For in Australia we did not need that revolution to get responsible government because of what had happened in Canada. So, in a way these people are Australian patriots, too.”

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the world experienced a revolutionary fever. The United States and France became republics in the late 1700s, while the Spanish and Portuguese colonies in continental South America gained independence early in the following century. The people in the Canadian colonies took note.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Under the provisions of the Constitution Act of 1791, Lower Canada and Upper Canada were each ruled by a clique of unelected, mainly British officials. At the top of the hierarchy stood the Lieutenant-Governor, who was appointed by the British Crown. The Lieutenant-Governor was advised by an executive council, which he appointed. Laws were made by a legislative council, whose members the Lieutenant-Governor also appointed — for life. The people of each colony were represented by an elected legislative assembly, but the Lieutenant- Governor could veto any bill passed by the elected assembly and could dissolve the assembly “whenever he shall judge it necessary or expedient.”

The chasm between the rulers and the ruled was especially wide in Lower Canada, where the French-Canadian citizens, many of whom had lived on their land for generations, were subjugated to English-speaking imperialists who rarely had their best interests at heart. Beginning in the early 1800s, French-Canadian politicians, led by lawyer, seigneur, and founder of the Parti Patriote Louis-Joseph Papineau, attempted to achieve reform through peaceful, parliamentary means. But the colonial rulers rejected these attempts.

Finally, in 1834, Papineau and the Parti Patriote presented a manifesto known as the Ninety-Two Resolutions — first to the legislative assembly of Lower Canada and later to the British Parliament in London, England. The Ninety-Two Resolutions called for a reform of government that would take power away from unelected officials and place it instead in the hands of a democratically elected parliament.

“It is a … vicious form of government that makes the happiness or unhappiness of a country dependant on an executive over which it has no influence, and with which it has no common or permanent interest,” resolution twenty-eight stated. “[T]he extension of the elective principal is the only refuge that provides for a future of equal and sufficient protection for all inhabitants of this province.”

When the British government categorically rejected the Ninety-Two Resolutions, the people of Lower Canada were incensed. Throughout the spring and summer of 1837, the Parti Patriote, led by Papineau, held a series of public assemblies in communities up and down the St. Lawrence River Valley that culminated in a two-day assembly at Saint- Charles-sur-Richelieu on October 23 and 24, 1837. This pivotal meeting brought together five thousand people from six counties along with thirteen Patriote members of the legislative assembly, including Papineau himself.

At the end of the assembly, the delegates adopted a formal declaration — which many historians attribute to Papineau, although he did not sign it — known as the “Address of the Confederation of the Six Counties of Saint-Hyacinthe, L’Acadie, Rouville, Richelieu, Verchères and Chambly to their fellow citizens of Lower Canada.”

“Fellow citizens! Brothers of a common affliction! All of you, whatever origin, language, or religion you may be, to whom equitable laws and the rights of man are dear; whose hearts beat with indignation at the sight of the innumerable insults that your communal homeland has had to bear; and who have so often felt a justified alarm, when contemplating in your souls the dark future that mismanagement and corruption forebode for this province and for your children,” the declaration stated. “In the name of your homeland and of the next generation, whose hopes rest only on you, we urge you, by systematic organization of your parishes and townships, to adopt the only possible stance that can win respect for yourselves and the success of your demands.”

It went on to urge citizens to elect their own local magistrates and to organize militias to defend their rights and property against the British colonial government and its armed forces.

Building on years of pent-up grievances, the declaration propelled the Patriotes into an armed insurrection against the British Empire that came to be known as the Rebellion of Lower Canada. In 1837–38, militants took up arms against the British in a series of short, sometimes bloody battles. But, with the might of British army detachments and local loyalist volunteers, the colonial government easily put down the insurrection. The government also quelled a parallel rebellion in Upper Canada, which involved both Upper Canadian militants and American sympathizers. In the end, many of those who fought for change, including Papineau, took refuge in the United States. Hundreds of others were killed or captured, and British forces burned to the ground the homes of many Patriotes.

The memoirist Louis-Léandre Ducharme, a twenty-two-year-old clerk, was arrested on November 7, 1838, for participating in an uprising in Châteauguay, southwest of Montreal, during which the Patriotes captured and held prisoner several English landowners. Ducharme and his compatriots were imprisoned, along with other insurrectionists, in Montreal’s Pied-du-Courant prison.

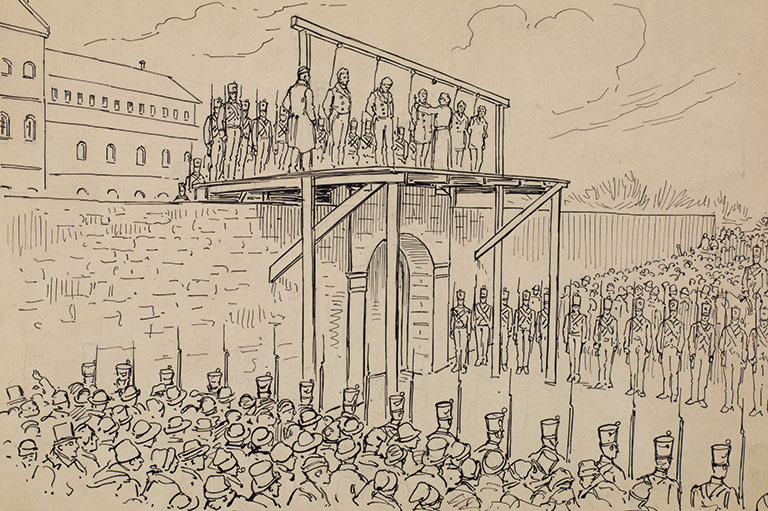

After trials in military courts, ninety-nine Lower Canadian Patriotes, including Ducharme, were condemned to death. The first two to be hanged, on December 21, 1838, were Joseph-Narcisse Cardinal and Joseph Duquette, the leaders of the Châteauguay Patriotes. Cardinal and Duquette had been captured in November 1838 while leading an expedition to obtain weapons from the Mohawk community of Kahnawà:ke, south of Montreal. The Patriotes had intended to use the arms in their fight against the British, but Mohawk warriors surrounded them, took them prisoner, and delivered them to colonial authorities.

Ten more executions followed over the ensuing weeks, while Ducharme huddled in his cell, dreading the gallows. “We stayed for thirty days in solitary cells without being let out, either by day or by night; we slept on the bare floor with only a blanket for both a mattress and a cover, during that season when frost blanketed the inside walls of our cells,” he wrote.

Advertisement

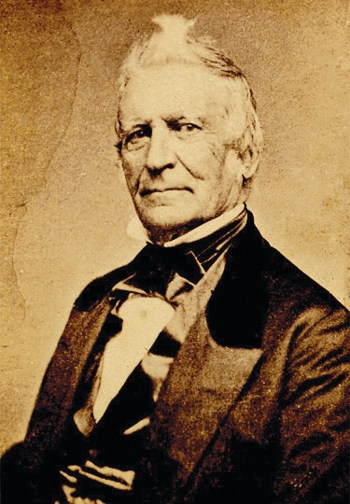

After twelve executions, the colonial authorities grew concerned over the prospect of carrying out the remaining death sentences. Hanging the condemned men would make them martyrs in the eyes of French Canadians and might provoke further violence, while liberating them could spark resentment among those in the English population who wanted no clemency toward the men they saw as traitors. The British colonial secretary, Lord Glenelg, intervened to request that executions cease. Conditional pardons were granted to some prisoners. But fifty-eight prisoners remained in Lower Canada, while ninety-two captives — the majority of whom were Americans — were still incarcerated in Upper Canada. It was Upper Canada Lieutenant-Governor George Arthur who proposed a course of action for dealing with them.

Prior to taking up his post in Upper Canada in March 1838, Arthur had ruled for thirteen years as Lieutenant-Governor of the notorious penal colony of Van Diemen’s Land (now the Australian state of Tasmania). There he had left a dark legacy, instituting the harsh methods that gave Van Diemen’s Land the reputation of being the worst penal colony in the British Empire. During his time in office, he had executed some 250 captives for offences committed while in the colony. At the time, the Australian penal colonies formed a dumping ground not only for criminals but also for political prisoners from all across the British Empire. Arthur saw these colonies as the solution to his problem. On September 25, 1839, Ducharme and the other prisoners were given the word: Instead of being hanged, they were condemned to deportation to a penal colony and lifetime exile on the Australian continent.

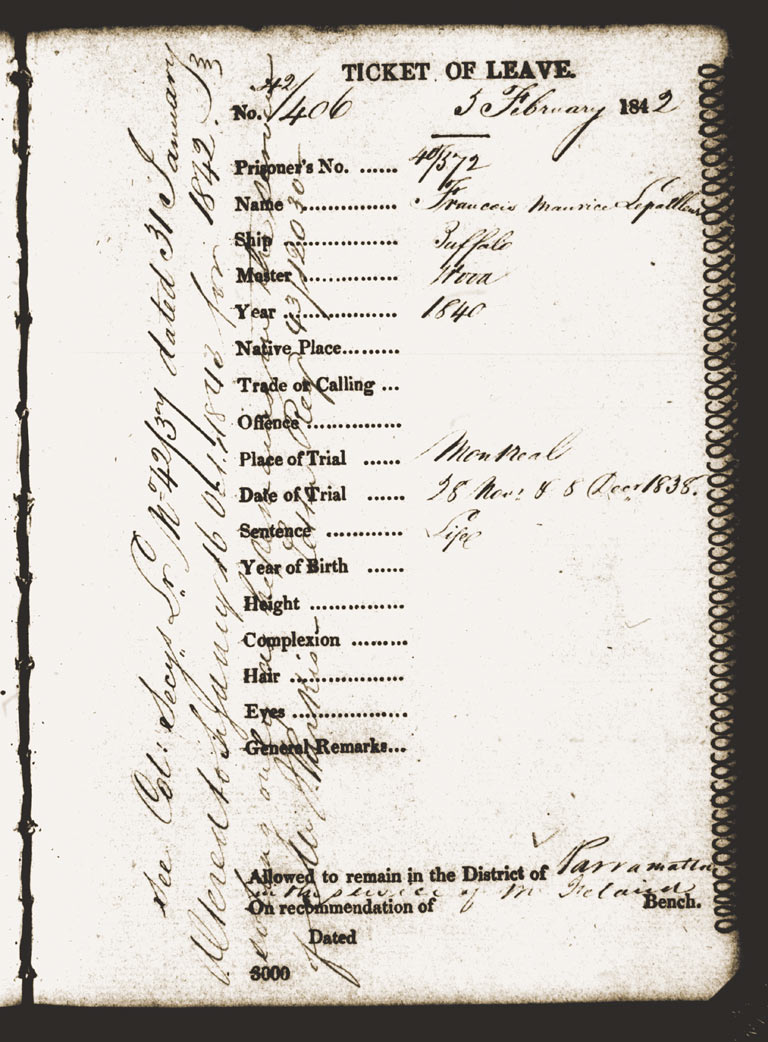

That very day, Ducharme’s friend and fellow inmate François-Maurice Lepailleur — a thirty-two-year-old bailiff and father of two who had been captured during the raid on Kahnawà:ke — began keeping a secret diary that he hoped someday to share with his family. “There is no greater sorrow for a man than to become a prisoner and an exile, not knowing if he will ever recover his liberty,” Lepailleur wrote. “Oh! What sad reflections, for a father who leaves behind a dear wife and two darling little children, who are the subjects of my dearest thoughts.”

After transport to Quebec City, the prisoners from Lower Canada, later joined by those from Upper Canada, were herded aboard HMS Buffalo — the same ship that had brought the first settlers to South Australia in 1836. The thirty-seven-metre-long, three-masted, wooden sailing ship left Quebec and commenced its journey to the South Pacific on September 28, 1839. The prisoners were confined below decks day and night, except for a daily two-hour exercise break. They were lodged in a dark, hot, and crowded hold where light penetrated only through the grilles that covered the hatches. Their food consisted of oatmeal porridge served in buckets that fed twelve men each, pea soup, ship’s biscuit, and salt beef. “Our daily allowance of water was one pint each, a ration quite insufficient to quench the burning thirst brought about by the salty provisions,” Ducharme wrote.

After rumours of a mutiny circulated, shipboard authorities cracked down even harder on the prisoners. “From that day on, we had to go to bed at precisely eight o’clock and not get up before six o’clock in the morning, except in case of urgent need,” Ducharme wrote. “We were so strictly prohibited from speaking with each other that the sentinel had orders to shoot anyone who said a word.”

The voyage to Australia lasted five gruelling months. Lepailleur, tormented by dreams of his wife and children, found solace in reading the Bible and reciting Sunday prayers. Some of the other men spent their time aboard the ship learning to read, he noted. The heat in the tropics was torturous. On deck, pigs and sheep were penned into flat-bottomed boats, where water accumulated after rainfalls. “The sailors bottled this water, so infused with manure that it was rust-coloured, and sold the bottles to us in exchange for a shirt or a pair of pants, and such was the violence of our thirst that the water seemed to us like honey,” Ducharme wrote.

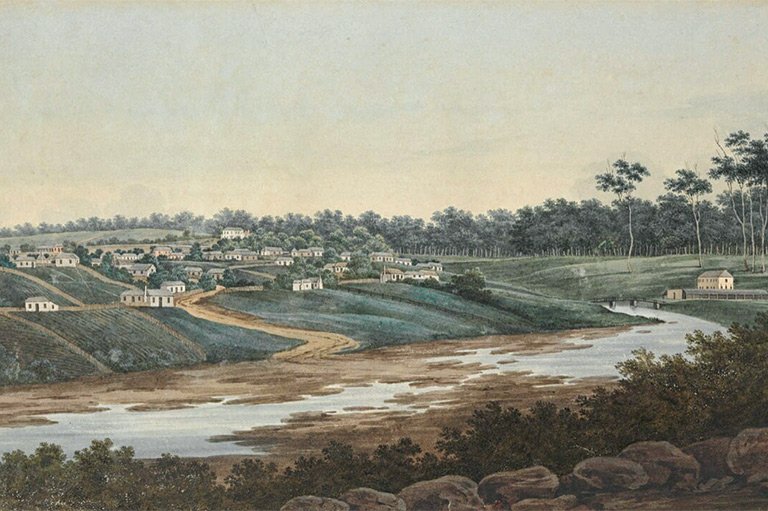

At last, on February 13, 1840, the Buffalo reached Hobart Town, Van Diemen’s Land, where the Upper Canadians and Americans were herded off the ship. According to the memoirs of American prisoner Robert Marsh, after hearing that the vast majority of the prisoners from Upper Canada were Americans, the island’s Lieutenant-Governor, John Franklin — nephew of the American revolutionary Benjamin Franklin — exclaimed: “So much the worse. You Yankee sympathizers must expect to be punished. I do not consider the simple Canadians, especially the French in Lower Canada, so much to blame, as they have been excited to rebellion by you Yankees.”

Given political-prisoner status, the Upper Canadians and Americans were set to work building roads at Sandy Bay in Hobart Town. Meanwhile, the Buffalo continued to Sydney, New South Wales, delivering the Lower Canadians there on February 25. Once the arrival of the prisoners became public knowledge, hysteria gripped the town. Citizens questioned the common sense of the British government’s decision to send the French-Canadian rebels into their vicinity. “Unfortunately, word had reached the press from Canada about the French-Canadian patriots, that they were pirates and cutthroats, basically in rhetoric that today we would associate with terrorist organizations like ISIS or al Qaeda,” Australian historian Tony Moore said.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

During this period, influential people in the city advocated for the prisoners to be transported further away to Norfolk Island, a hellish penal colony in the South Pacific Ocean some 1,675 kilometres northeast of Sydney. The island was actually home to two penal colonies — the first ran from 1788 to 1813, while the second opened in 1825. Intended for the worst of the convicts — those who attempted mutiny or who committed a crime while in a penal colony — Norfolk Island was a harsh and a degrading place where prisoners were subject to frequent floggings by guards and to the risk of rape at the hands of fellow prisoners.

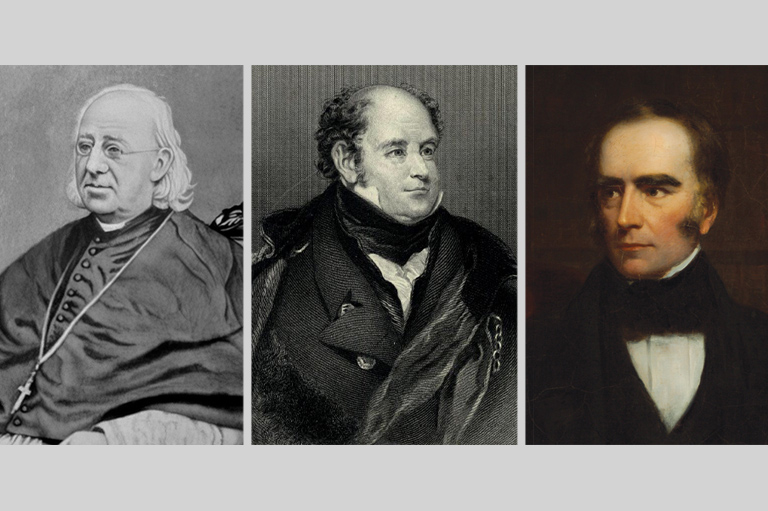

As bad as things appeared to be for the Patriotes, salvation came unexpectedly on February 27, when they received a visit from Catholic Bishop John Bede Polding. Polding, who later became the archbishop of Sydney, spoke perfect French and was therefore able to hear the prisoners’ confessions. After listening to the details of their harrowing experiences aboard the Buffalo, he went to see the governor of New South Wales, Sir George Gipps, who had served in the 1836 Gosford Commission in Lower Canada, studying the Patriotes’ grievances before the insurrection broke out. As a result of this, the governor listed the Lower Canadians as political prisoners, meaning they would not be shackled, and decided against transporting them to Norfolk Island.

The Lower Canadians left the Buffalo for the first time in nearly six months on March 11, 1840. Shortly after their arrival, the transportation of convicts to New South Wales ended, making them some of the last prisoners to be sent to that colony. As for the Buffalo, the ship met its fate on July 28, 1840, when it crashed ashore during a storm at Mercury Bay in New Zealand. Later, when discovering this news, Lepailleur rejoiced: “What cruelties did we endure aboard that miserable ship! I shall remember it all my life. God has given them what they deserve.”

After leaving the Buffalo, the Patriote prisoners were transported by barge up the Parramatta River to the Longbottom Stockade. Established in 1792, the stockade was located along the Parramatta Road, approximately halfway between Sydney in the east and the inland town of Parramatta in the west. The road was commonly used to transport convicts destined for Parramatta, and the stockade had formerly served as an overnight way station for those convicts. In 1840, this area was deemed hazardous due to the presence of thieves and escaped convicts. As well, there were groups of Aborigines who were resisting the British colonization of their land.

Ducharme described the stockade as “a sort of barracks or prison, which formed a square: there were several small, detached buildings, such as a kitchen, a toolshed, etc.” Here the Patriotes were confined in huts measuring three metres by five metres, each hut housing between fifteen and eighteen men. Ducharme noted how the sergeant in command of the platoon of British soldiers stationed at the stockade warned the new prisoners of the punishments that awaited them if they failed to toe the line: “He told us that if we broke the prescribed bounds we would be liable to fifty lashes, and that we were forbidden, under penalty of severe punishment, to wander about the interior of the settlement without permission, and that for neglect of our set tasks we would be punished with the lash. For disobedience or lack of respect to our superiors and for various other infractions of little consequence we would be rigorously punished.”

Two days after their arrival, the Patriotes were ordered to undertake the repair and widening of the Parramatta Road — work they would continue to perform during the entire term of their imprisonment. Equipped with wheelbarrows, shovels, and hammers, they unloaded stone from a wharf on the Parramatta River, broke the stone into small pieces, and transported it by ox cart to the road site, where they set about their construction duties. For lunch they were given coarse bread and meat, which had often spoiled in the heat of day. “We were never given dinner,” Ducharme wrote. “After working for the entire day, we were locked up for the night, exhausted and hungry, at around five-thirty or six o’clock.”

Advertisement

As the weeks passed and it became apparent that the Canadians were not a threat, Governor Gipps removed the soldiers and instead installed a superintendent, Henry Baddeley (or Baddely), to oversee the stockade. Baddeley was Irish and spoke perfect French. According to Lepailleur’s diary, he was also a notorious womanizer and an alcoholic who suffered from syphilis. Although he at first seemed sympathetic to the Canadians, speaking to them in their native French, he later grew tyrannical and erratic. Lepailleur wrote that flogging was a common punishment, and he gave the example of one prisoner who crossed the Longbottom Stockade quadrangle without permission and received one hundred lashes.

On numerous occasions Baddeley threatened his personal assistant — the Patriote Joseph Marceau, from the village of Saint Cyprien-de-Napierville — with physical violence. “He was a veritable tyrant, a man without character, one given to abusing his power in order to ill treat us every time he could find an opportunity of doing so,” Ducharme wrote.

Baddeley set up a hierarchical system in the stockade, appointing certain prisoners as overseers to supervise and to control the others. This created resentment, particularly toward the prisoner appointed as clerk and head overseer, Louis Bourdon. Bourdon had previously been a merchant, justice of the peace, and school commissioner in Saint- Césaire, Lower Canada. Lepailleur — who was reassigned in May 1840 from road construction duty to the position of gate sentry at the stockade — watched as morale disintegrated. Fights broke out between the exiles following the theft of food or goods, and the powerful solidarity that bound the men together weakened day by day.

On June 7, 1840, Lepailleur wrote bitterly of the divisions that arose between prisoners one Sunday, as they walked to the town of Parramatta to attend church: “We had to wear the government-issued prison uniforms, including caps, and that is what is most degrading…. Bourdon did not wear a single item of government-issued clothing; he was exempted by the commander…. He and the other overseers didn’t have to stand in ranks, but all the rest of us had to march three-by-three, like soldiers … and we didn’t have the right to talk too loudly, nor to walk too fast…. And we were all led by our dear Bourdon, who treated us worse than if he’d been a perfect stranger.”

The Patriotes were not forgotten by their fellow Canadians. In 1842 university student Antoine Gérin-Lajoie wrote the song “Un Canadien errant,” a tribute to the Patriotes’ estrangement from their homeland and the pain of exile. Adherents to the Patriote cause formed the Association de la Délivrance, with chapters in Montreal, Quebec City, and many smaller communities. Its goals were to lobby for the prisoners’ release and to raise money for their eventual return home. Meanwhile, American politicians engaged in serious lobbying with British ministers for the return of the American prisoners, whom they believed were being held illegally in Van Diemen’s Land.

In New South Wales, the Patriotes also had supporters. Catholic priests advocated on their behalf and Bishop Polding, while on a trip to Europe, presented a petition from the Lower Canadian prisoners to the British colonial secretary. An article in the July 25, 1840, issue of the Colonist, a Sydney newspaper, stated: “Some of our contemporaries are quarrelling whether or not Government ought to treat these Canadians with more lenity than they now experience. We urged upon the Government, when these men first arrived, the expediency of treating them in a different manner from other prisoners, if they did not receive conditional pardons or tickets of leave.”

A first step toward freedom came to the prisoners between 1841 and 1843, as, one by one, they were issued tickets of leave by the colonial government. Under this system, each prisoner was assigned to a private employer, who paid him wages and gave him room and board. No longer confined to the stockade, the Patriotes were dispersed to different parts of the colony. Ducharme was assigned to work as a clerk for a furniture maker in Sydney. Lepailleur was also sent to Sydney, to work for a justice of the peace. Although their lives improved, they were still not permitted to leave New South Wales or to return to Canada.

Bourdon and another Lower Canadian exile, François- Xavier Prieur, were offered a chance to abscond from New South Wales when, as they were fetching supplies for their employer near the Sydney harbour, French merchantmen offered them a passage to North America. Prieur considered the offer seriously but decided to turn it down, knowing that without a pardon he could not return to Canada. “In the case of complete success, I could see nothing better in the final result than the obligation to live and to die outside of my native land,” he wrote. “I communicated to my friend, Mr. Bourdon, the result of my meditations.… I told him that there was every reason to hope for a general pardon, and that, in these circumstances, our escape would be equivalent to perpetual banishment.” Bourdon, by contrast, seized the opportunity and embarked on the French vessel that took him to New York State.

Finally, in 1844, Prieur’s prediction came true: After strong international condemnation for keeping political prisoners as convicts, Britain’s Queen Victoria granted pardons to the Australian exiles of the rebellions in Upper Canada and Lower Canada. On July 10, 1844, the first thirty-eight Canadians — including Lepailleur and Ducharme — sailed out of Sydney on the Achilles. In his diary, Lepailleur wrote: “By God’s grace we are leaving our land of exile. Adieu a thousand and a thousand times, land of exile! Land of slavery! Land of a thousand sorrows.”

The majority of the exiles returned to Canada and the United States between 1844 and 1848, although the last one arrived home in 1860. Some took longer than others due to bureaucratic delays and the need to save or to raise money for the voyages. Lepailleur arrived in Canada in January 1845, whereupon he reunited with his beloved wife. His diary was published posthumously under the title Journal d’un patriote exilé en Australie 1839–1845. Ducharme published his Journal d’un exile politique aux terres australes in 1845.

Prieur arrived in Montreal in September 1846. Ironically, in 1875, he became Canada’s superintendent of prisons. Bourdon, who had escaped to the United States, returned to Canada after the general amnesty. In 1855 he was elected mayor of the town of Farnham in Canada East (present-day Quebec). Prieur and Lepailleur stayed in touch until the end of their lives and died within a month of each other in 1891. Along with Leandre Ducharme, who died in 1897, they now rest at the foot of the Patriote obelisk that was erected in 1858 in Montreal’s Notre-Dame-des-Neiges Cemetery.

Two of the Lower Canadians, Louis Dumouchel and Ignace-Gabriel Chèvrefils, died in captivity at the Longbottom Stockade. A few of the Americans and one Lower Canadian, Joseph Marceau, chose to stay behind in Australia. Marceau, who had been Baddeley’s personal assistant in the Longbottom Stockade, married an Australian woman. The couple settled in the town of Dapto, ninety-five kilometres south of Sydney, where they raised vegetables, owned a grocery store, and had eleven children.

Baddely died of syphilis on March 2, 1842. Franklin, who ended his term as Lieutenant-Governor of Van Diemen’s Land in 1843, died a frigid death in the Canadian Arctic in 1847 while leading a doomed expedition in search of the Northwest Passage.

Due to pressure by Canadian politicians and by the public, the Province of Canada gradually achieved responsible government in the 1840s, and it was formally granted in 1848. Nova Scotia and the Province of Canada were the first British colonies to receive responsible government — a result of the grievances that had motivated the Lower Canadian Patriotes and their Upper Canadian counterparts in their rebellions years before. It was not long until, in the mid-1850s, the colonies of New South Wales, Tasmania (formerly Van Diemen’s Land), and New Zealand received responsible government without a shot having been fired — another testament to the Patriote legacy.

“Britain’s ready acquiescence in granting a significant degree of democratic self-government in its Australian colonies in the 1850s and ’60s owes something to her experience in Canada, both of rebellion, but also the peaceful, piecemeal transition to responsible government under the post- Durham constitution in the 1840s,” Moore wrote in Death or Liberty. “In the end, the hardships endured by the patriot convicts had not been in vain.”

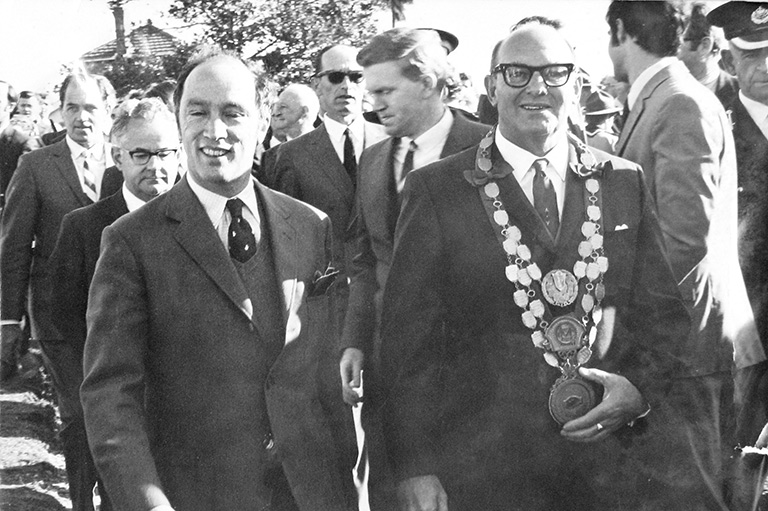

On May 18, 1970, Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau visited Australia to unveil that country’s first memorial dedicated to the fifty-eight French-Canadian exiles. Joseph Marceau’s descendents attended the event. This memorial, located close to where the Patriotes landed, ensures, along with other monuments and commemorations, that the legacy of the Canadian exiles in Australia will not soon be forgotten.

In today’s environment of misinformation and disinformation, it can be hard to know who to believe. At Canada’s History, we tell the true stories of Canada’s diverse past, sharing voices that may have been excluded previously. We hope you will help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past, highlighting our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages – award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts. Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement