Exploration and Empire

As the end of the eighteenth century approached, the interior of the northwest coast of North America remained terra incognitato European science and knowledge. Indigenous peoples who lived there and harvested its abundant resources to their prosperity, profit, and political power — backed by trading relationships and, sometimes, warfare — were fully conversant with its geographical dimensions. These were cordilleran lands where the Kootenai, Shuswap, Blackfoot, and others had crossed mountain passes for generations. When fur trader and trade visionary Alexander Mackenzie transited through these lands in 1793 on his famed crossing from Fort Chipewyan, on Lake Athabasca, to the Pacific Ocean, he had no way of knowing whether the Indigenous people he met would greet him as a friend or take up arms against him to defend their territory from incursion.

In the event, Indigenous peoples were vital to Mackenzie’s proceedings. In particular, they gave critical advice in pointing a way to the continent’s western rim and in doing so directed him away from a perilous passage down the Fraser River, which would have been the end of his voyage and might well have ended in death for himself and members of his party.

Make no mistake: Thanks to Indigenous advice, Mackenzie was the first person in recorded history to cross the continent north of Mexico. All the same, the scheme was devised by him alone, and he led it to a successful conclusion. His explorations, recounted in his classic travel narrative published in 1801 and entitled Voyages from Montreal on the River St. Lawrence through the Continent of North America to the Frozen and Pacific Oceans in the Years 1789 and 1793, disclosed the secrets of northwestern North America to British, European, and American publics. The results gave new impetus to ambitions of trans-Pacific trade and British trade expansion on the Pacific coast and adjacent seas. All of this foreshadowed the prospect of Canada as a country spanning the North American continent from coast to coast.

Aged thirty-one when he undertook his journey, Mackenzie possessed exceptional characteristics: He was enterprising, self-sufficient, prescient, able to endure unimaginable hardships and to lead from the front. His passage to the western edge of the continent reveals how difficult were the geographical circumstances faced by him and his party; furthermore, how complex and demanding were the relations posed by the Indigenous peoples (of various nations and groups) in the course of his passage to and from Pacific tidewater.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

We situate Mackenzie and his party in time. It was the spring of 1793. Preparations for the coming adventure were well underway at Fort Fork, a rustic collection of wooden buildings on the banks of the Peace River, some eight hundred kilometres upriver from Fort Chipewyan, a key North West Company establishment on Lake Athabasca. After leaving Fort Chipewyan the previous autumn, Mackenzie and his men had built Fort Fork and spent the winter there, using it as an advance base for their planned trek to the Pacific Ocean. As soon as the ice on the river broke up in May, Mackenzie intended to make a fast dash to the Pacific Ocean and then back to Fort Chipewyan in a single summer. The journey across formidable landscapes of rivers, portages, and plateaus, with no map and no known path to follow, would prove arduous and dangerous in the extreme.

Mackenzie’s purpose in attempting this journey was three-fold: first, to determine the distance from Fort Chipewyan to the Pacific coast and thus to establish the breadth of North America in the latitude of approximately fifty-five degrees north; second, to discover the nature of the mountains, valleys, and rivers of the far west in those latitudes; third, and not least, to open trade in furs with the Russians, who had already established trading posts at Cook Inlet, Alaska, and elsewhere on the Pacific coast. By bringing furs from the North American interior to Pacific trading posts, and thence into the markets of China and Japan, Mackenzie aimed to change the concept of British North America from a colony focused on supplying the markets of the east coast from the hinterland of the West to a continent-wide keystone of the British Empire, trading equally adeptly out of its Pacific and Atlantic ports.

The waters and shoreline of the northwest coast were already well known to Spanish, Russian, British, French, and American merchant mariners and official explorers who plied the waters of the Pacific and traded along its coast. The missing piece remained the fabled Northwest Passage through the continent that would link the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Armchair geographers in Europe, the United States, and eastern Canada dreamed of finding a navigable passage between these two oceans. Attempts to find an entrance to the passage had been made from both the east coast and the west coast — “the backside of America,” as one Elizabethan called it — going back to the late sixteenth century.

While mariners explored the coastal waters, overland came the fur-trading explorers. In 1775, Peter Pond, one of the founders and organizational masterminds of the North West Company, imagined a riverine route from Great Slave Lake, in present-day Northwest Territories, to Cook Inlet in the Gulf of Alaska — though, in the end, the route proved non-existent. In sum, the northwest coast remained, as the editor of a book by the French navigator Jean-François de Galaup, Comte de Laperouse, called it, “the theatre of all the geographical fictions.” A route between the oceans, if found, would unlock the fabled markets of the Orient. On the northwest coast — where options to find an entrance to the elusive Northwest Passage were narrowing — the British Admiralty ordered an exploratory expedition. In the summer of 1793, having left Portsmouth, England, two years previously, Captain George Vancouver was examining every inlet and sound on the high-latitude coast of what is now British Columbia, his rain-soaked boat parties from the sloop of war Discovery and the brig Chatham working with precision towards the Skeena River.

Now came the magic — even supreme — moment, for the long tentacles of British sea power were about to touch the outstretched hand of British overland exploration, personified in Mackenzie’s extraordinary journey. A pincer movement, so to speak, was at work. It closed on a highly complex Indigenous world of many peoples and many languages and dialects, a world in which rivalries were vibrant and warfare not unknown, a world, too, awakening to the material reality of the industrial age. This was one of the most populous parts of Indigenous North America. On the cusp of change, the New World was being reordered. The Indigenous nations and peoples meant to be part of the changes, and they entertained the strangers that came from far away, proud and confident as they were of their own power, prestige, and future.

Mackenzie was born in 1762 in Stornoway, on Scotland’s Isle of Lewis. His father was a property manager who also commanded the local militia. Arriving as a young scholar in the British colony of New York at age twelve, he was sent for further education to Montreal, where he learned accounting in a firm that formed one of the partnerships in the North West Company. The rival Hudson’s Bay Company had possessed a charter from the British Crown since 1670 giving it exclusive rights of trade in the 3.9 million square kilometres of lands drained by all the rivers flowing into Hudson Bay and known as Rupert’s Land. The North West Company had no such charter and necessarily worked along the margins of HBC territory. In Mackenzie’s time it outflanked the HBC in a broad semi-circular sweep of lands that drained northwest and west of Rupert’s Land, including the Athabasca River watershed. Mackenzie had keen business abilities and sharp instincts. International trade was of compelling interest to him. Sent west by principals in the firm who realized his immense promise, Mackenzie was a rising star in the company.

At Fort Chipewyan, Peter Pond’s geopolitical thinking and mastery of long-distance land trading enraptured the younger Mackenzie. Pond had intended to pursue the possible trails to Cook Inlet — a 350-kilometre-long inlet in the Gulf of Alaska that was thought, at the time, to be the mouth of a great river flowing east to west across the continent. But Pond had been obliged, by company demand, to withdraw from the wilderness — a cloud over his head because of an alleged murder committed against a rival trader.

Mackenzie seized the day; he embraced Pond’s abandoned project. In 1789 he went in search of “Cook’s River.” Yet, after travelling for many weeks on a river the Dene called Deh-Cho, or Great River, he was disappointed to reach the discharge of those waters into the Arctic Ocean. The Rocky Mountains barred his way to the Pacific and to the Russian trading posts on the west coast of Alaska. Mackenzie’s river voyage — five thousand kilometres in that long summer of 102 days — is a harrowing tale. Privately, to his cousin Roderick, he called Deh-Cho “the River Disappointment.”

His objective remained: to stand on the shores of the Pacific Ocean by going west in northern latitudes. Returned to Fort Chipewyan, he knew he did not have the scientific knowledge to record longitude by anything other than unreliable dead reckoning. To remedy this deficiency, he went to London on furlough. There he mastered the arts of navigation and surveying. He learned to use the sextant to measure the angle between the Earth’s horizon and heavenly bodies, such as the sun or moon, and how to use this measurement to calculate latitude. He learned how to sight the moons of Jupiter, which, in their predictable orbit around that planet, form a kind of astronomical clock. He learned how to cross-reference his sightings with the data gathered in the Nautical Almanac and there by determine his longitude. With this knowledge, he could place on a blank chart his exact geographic location. Scientific method could now replace geographical speculation: Mackenzie was armed for the supreme challenge of finding and determining the position of the continent’s western shore.

In early May 1793, as the ice broke up on the Peace River, Mackenzie made the final preparations for his voyage. His Athapaskan interpreter feared the worst. “My winter interpreter,” wrote Mackenzie when about to leave Fort Fork, “with another person whom I left here to take care of the fort and supply the natives with ammunition during the summer, shed tears on the reflection of those dangers which we might encounter in our expedition, while our own people offered up their prayers that we might return in safety from it.”

On May 9, 1793, Mackenzie and his men set out on their journey. The exploring party consisted of ten people — Mackenzie, his kinsman Alexander MacKay (or McKay), six Canadian voyageurs, two Athapaskan hunter-interpreters — and a dog. In a birchbark canoe 7.6 metres in length and built to his specifications, Mackenzie shipped provisions, presents for the Indigenous people he would meet, arms, ammunition, navigational instruments, and baggage – a total of a tonne and a half of cargo.

When the river ice broke up, he began his way upstream. His party faced strong headwinds and swift currents. The men progressed upriver through the grassy country, past herds of buffalo attending their young. The ground rose to a considerable height — a vast, magnificent theatre of nature, with groves of poplars and other softwoods. After several days the river narrowed and the distant mountains came into view. Grizzly bears were seen — and avoided. Mackenzie’s voyageurs worked tirelessly, often in fear of their lives as they manoeuvred their canoe around boulders amid the raging current.

His voyage up and through the ramparts of the Rockies was hazardous. If the canoe were to be wrecked or capsized, the men would lose their provisions, ammunition, trade items, gifts, dried food, rum, and navigational instruments. The afternoon of May 20 found them towing their canoe upriver, battling a current so fierce they could not paddle against it. “The agitation of the water was so great, that a wave striking on the bow of the canoe broke the [tow rope], and filled us with inexpressible dismay, as it appeared impossible that the vessel could escape from being dashed to pieces and those who were in her from perishing,” Mackenzie wrote. “Another wave, however, more propitious than the former, drove her out of the tumbling water, so that the men were enabled to bring her ashore.” Ahead of them, the river formed “one white sheet of foaming water.” It was time to rest for the night.

As they continued to ascend the mountains toward the Continental Divide, the difficulties, discouragements, and dangers of the enterprise led Mackenzie to decide to travel overland. Over the following days, they cut a trail through the woods, about four hundred metres from the river. Looping their tow ropes for leverage around the tree stumps that lined their newly cut road, they hauled their canoe up the slope, “so that we may be said, with strict truth, to have warped the canoe up the mountain ... by general and most laborious exertion,” Mackenzie wrote. He broke out the rum keg at the evening meal.

On May 24 they arrived at a river, allowing them to continue their voyage by canoe. But this river, like the others on which they had travelled, flowed west to east; they had not yet crossed the Continental Divide. Based on previous conversations with Indigenous traders and hunters, Mackenzie believed that a river flowing east to west, into the Pacific Ocean, must lie nearby. However, his efforts to find it were fruitless.

In the afternoon of June 9, Mackenzie met a party of thirteen or fourteen Sekani. After conversing with them for several hours, giving them gifts and sharing his provisions, eventually he was told of “a large river that runs towards the midday sun” and that could be reached by crossing three lakes and descending a small river. The Sekani also told him of the people who lived beside the “Stinking Lake” — which Mackenzie interpreted as meaning the Pacific Ocean — and whose territory could be reached by travelling “during a moon.” They added that the coastal people “trade with people like us [Europeans] that come there in vessels as big as islands.”

Accompanied for the following week by a Sekani guide, Mackenzie continued his journey with renewed vigour. Sometime in mid-June, the party of explorers crossed the Continental Divide, for on June 17 Mackenzie wrote: “At length we enjoyed, after all our toil and anxiety, the inexpressible satisfaction of finding ourselves on the bank of a navigable river, on the West side of the first great range of mountains.”

"It appeared impossible that the vessel could escape from being dashed to pieces.”

Advertisement

The river was wide and deep, the current very slack, but as they proceeded southwards the river narrowed and the land rose high on either side. Near the end of June they came to a small settlement, where Mackenzie asked the Indigenous people for information about the river ahead of them. Throughout his journey, Mackenzie had taken meticulous compass bearings, estimated the distance travelled each day by dead reckoning, and — when conditions allowed — taken “horizon” measurements to ascertain his latitude. He therefore had a fair idea of his geographical location, despite having no knowledge of the terrain ahead. The Indigenous people told him he was travelling on a river they called Tatouche Tesse. Based on their description, and on his own geographical calculations, he considered that Tatouche Tesse could be a branch of the Columbia River, which emptied into the Pacific Ocean at about forty-six degrees north latitude, much farther south than his intended route. Although he was mistaken about this, he would have proceeded down Tatouche Tesse (later named the Fraser River) had he not calculated that he could not make that voyage to the Pacific and back to Fort Chipewyan in one season; the extra distance involved in the detour south would add too many days to the journey. In addition, the Indigenous people warned that going down-river on the wild and furious Tatouche Tesse would lead to certain death. Here and elsewhere his western route was determined on the basis of Indigenous advice.

But forsaking the journey down Tatouche Tesse meant returning to a point upriver where an overland trail, described to him by the local people, would lead to another river that discharged into the Pacific. In his diary on June 23, Mackenzie wrote: “I now called those of my people about me, who had not been present at my consultation with the natives; and after passing a warm eulogium on their fortitude, patience, and perseverance, I stated the difficulties that threatened our continuing to navigate the [Tatouche Tesse] river, the length of time it would require, and the scanty provision we had for such a voyage. I then proceeded for the foregoing reasons to propose a shorter route, by trying the over-land road to the sea. ... At all events, I declared, in the most solemn manner, that I would not abandon my design of reaching the sea, if I made the attempt alone, and that I did not despair of returning in safety to my friends. ... This proposition met with the most zealous return, and they unanimously assured me, that they were as willing now as they had ever been, to abide by my resolutions, whatever they might be, and to follow me wherever I should go.”

Returning upriver to a point near present-day Quesnel, B.C., he and his party pressed west, against the current of a stream he called West Road River. Storing the canoe and caching supplies to await their return, he and his companions took to the trails. They sought out and found a track known as the Nuxalk-Carrier Grease Trail, so-called because the Nuxalk and Carrier people used the track as a trading route, and it was marked by the oil of the eulachon, or “candle fish,” which dripped from the boxes carried by the traders. A major trade artery of both Indigenous and, by Mackenzie’s time, European goods, the trail linked Tatouche Tesse in the east with the village of Bella Coola in the west.

Mackenzie and his party passed north of the ancestral lands of the Tsilhqot’in. They were guided by one family and then the next. They climbed to a high plateau, then pressed westwards through “a sea of mountains.” Although it was July, the weather was as cruel as any they had encountered. On many days they were drenched by rain. On July 17, in biting winds, they came to the welcome lee of what Mackenzie aptly called Stupendous Mountain, rising 2,672 metres. Then, having crossed the last ridge, they came to the rim of the Bella Coola Gorge. Mackenzie and his men quickly descended a steep and wooded hill, a drop of about nine hundred metres in one afternoon. They came to a waterway he named Burnt Bridge Creek. They were now in a region heavily populated by the Nuxalk. To pursue their explorations and discoveries, both courage and tact would be required in the face of an uncertain reception from the local inhabitants.

The village Mackenzie arrived at on the evening of July 17 lay two hundred metres above the fast-flowing Bella Coola River. The inhabitants called it Nutleax, meaning “place without a waterfall,” for the stream on which it lay drained into the Bella Coola River by means of a large, placid delta. Mackenzie called it Friendly Village, for he and his men were generously treated there. “We had not been long seated round it [a fire prepared for them], when we received a large dish of salmon roes, pounded fine and beat up with water so as to have the appearance of a cream.” The people of the village made it clear that they wanted no venison to be carried downstream, nor iron to be used to fish for salmon — these they regarded as detrimental to a good salmon catch.

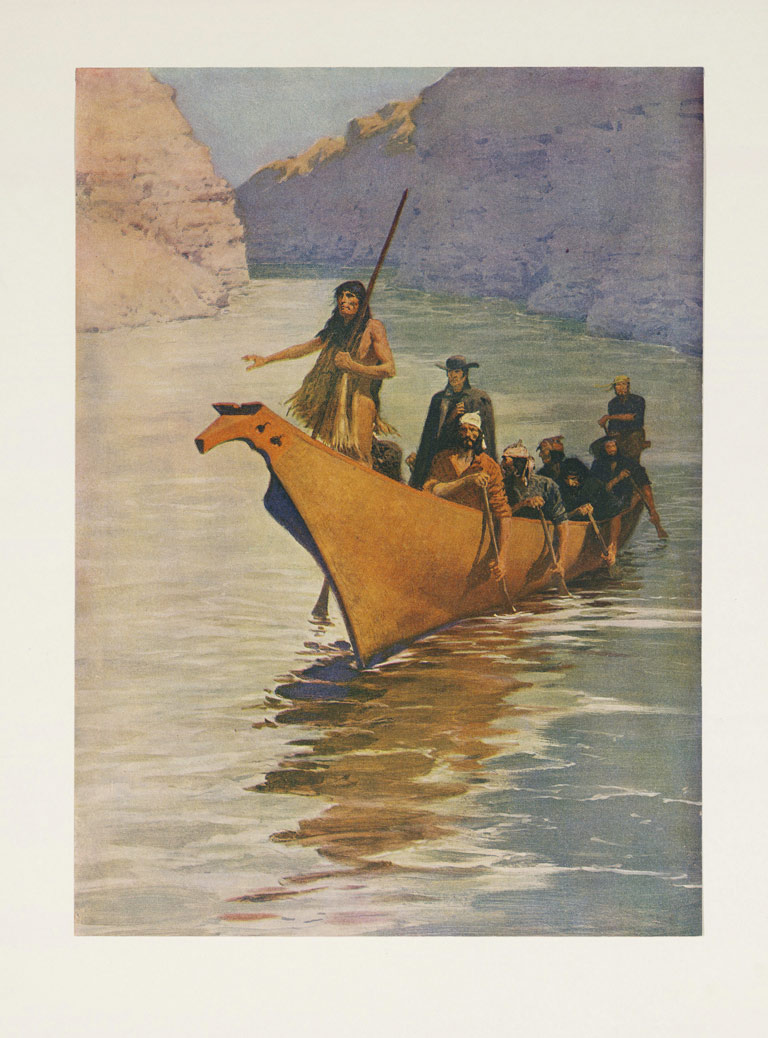

On July 18 Mackenzie’s part made its way day the Bella Coola River in canoes loaned to them by the inhabitants of Friendly Village. “At one in the afternoon we embarked, with our small baggage, in two canoes accompanied by seven of the natives. The stream was rapid, and ran upwards of six miles an hour. We came to a weir ... where the natives landed us, and shot over it without taking a drop of water. They then received us on board again and we continued our voyage, passing many canoes on the river,” Mackenzie wrote. “I had imagined that the Canadians who accompanied me were the most expert canoe-men in the world, but they are very inferior to these people, as they themselves acknowledged, in conducting those vessels.”

In their exhilarating course downstream, Mackenzie and his men came to Noosgulch, or Nooskultst. This was the Great Village on the north side of the Bella Coola River. There were sixty-one village sites. It was a world of diversity and of community under chiefly power. As they landed their canoes and made their way toward the village, Mackenzie wrote, “some of the Indians ran before us, to announce our approach, when we took our bundles and followed. We had walked along a well-beaten path, through a kind of coppice, when we were informed of the arrival of our couriers at the houses, by the loud and confused talking of the inhabitants.... When we came in sight of the village, we saw them running from house to house, some armed with bows and arrows, others with spears, and many with axes, as if in a state of alarm. This very unpleasant unexpected circumstance, I attributed to our sudden arrival. At all events, I had but one line of conduct to pursue, which was to walk resolutely up to them, without manifesting any signs of apprehension at their hostile appearance. This resolution produced the desire effect, for as we approached the houses, the greater part of the people laid down their weapons, and came forward to meet us. I was, however, soon obliged to stop from the number of them that surrounded me.”

All anxiety ended in a disarming bear hug given by the chief — a flattering reception. The chief’s son — whom Mackenzie later referred to in his journal as the “young chief” — gave Mackenzie a fine sea otter skin. It is charming to think that this was likely the same one Mackenzie proudly showed to Upper Canada’s Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe when the two men met in Upper Canada more than a year later on September 8, 1794. Elizabeth Gwillim Simcoe, the lieutenant-governor’s wife, recorded in her journal: “The otter skins are sold at a great price, by those who trade on the coast, to the Chinese.”

"As we approached, the people laid down their weapons and came forward to meet us.”

Mackenzie repaid the gift of the robe with presents to the chief and his son of a blanket, “several other articles,” and a pair of scissors, with which, the explorer explained, the chief could cut his beard — which he did. Here Mackenzie was shown some blue cloth decorated with buttons, possibly Spanish, he thought, and also a magnificent fifteen-metre cedar canoe, capable of carrying forty persons. Mackenzie never missed a trick in his search for authentic detail. For instance, he stated adamantly that the people of the northwest coast decorated their canoes not with human teeth, as the British mariner Captain James Cook had recounted in his narrative, but rather, as he observed, with the teeth of sea otters.

The chief said that about ten years previously he had taken a voyage toward the midday sun, where he had seen two large vessels full of men like Mackenzie — that is, Europeans — by whom he had been kindly received. These were the first Europeans seen by the people of Noosgulch. Mackenzie concluded that these had been Cook’s vessels and that the location must have been Nootka Sound, for Cook’s course had kept him otherwise offshore. Or perhaps they were the ships of the Scottish maritime fur trader James Strange trading near Cape Scott, on the northernmost tip of Vancouver Island.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

The warm initial response from the locals changed, and seemingly became more complex, the closer Mackenzie got to the open Pacific Ocean. The prevalence of mortality owing to disease may have explained the harsh response to the visitors when they entered the more westerly inlets and channels. Smallpox and other infectious diseases had passed this way and would do so again at later times. Marine life here was different, too, for this was the coastal environment of the precious sea otter.

Mackenzie continued his passage westwards, accompanied by the young chief who had given him the otter skin, to another village, which he named “Rascal’s Village.” This was Qomq’ts, now called Bella Coola. From here, he could see where the river on which he had been travelling ended, discharging itself into a narrow arm of the sea. This arm, at the head of Burke Channel, had been named North Bentinck Arm earlier that year by Vancouver. A ship’s boat from Vancouver’s expedition had visited the same village on June 1, 1793.

On the morning of July 20, Mackenzie and his company, borrowing a leaky canoe from the village inhabitants and taking two volunteers with them as guides, paddled down the river and into the salt sea. They were seventy-two days out of Fort Fork, which lay some 1,445 kilometres behind them. Success lay within Mackenzie’s grasp, but the ultimate challenge remained before he could start his return passage: He needed to determine his exact latitude and longitude, so that ships’ captains plying the Pacific coast could find the outlet of the river that had led him to the sea, and so that future fur traders could use the compass bearings and distance estimates that he had noted down during his overland trek to retrace his steps back to Fort Chipewyan on Lake Athabasca.

On July 21 Mackenzie and his men continued westward through the maze-like channels, searching for the best place to take an unimpeded astrological observation. That day they encountered fifteen Indigenous men in three canoes who, Mackenzie wrote, “examined every thing we had in our canoe with an air of indifference and disdain.” A past grievance surfaced. One of the men, in a manner Mackenzie classified as “insolent,” told Mackenzie that “a large canoe had lately been in the bay, with people in her like me, and that one of them, whom he called Macubah, had fired on him and his friends, and that Bensins had struck him on the back, with the flat part of his sword.” When they landed at a village in Elcho Bay later that day, an unwelcoming villager told Mackenzie that “he had been shot at by people of my colour” and that Macubah — Vancouver — had come there in his large canoe.

This oral evidence of alleged wrongdoing by Vancouver and his shipmate is unsupported by other documentation. Vancouver, who had been in this area in ships’ boats in early June, made no references to any difficulties with the Indigenous people he met. It’s also unclear whom the name Bensins was meant to designate. The ship’s surgeon and naturalist Archibald Menzies — whose name might have been misheard as Bensins — was not recorded to be part of any boat expedition. If by Bensins the complainant meant Master James Johnstone, then perhaps there was reason for his grievance: Johnstone, the leader of a ship’s boat, admitted to forcing entrance to a seaside dwelling. In any case, at the time Mackenzie reached the same locale, Vancouver was surveying the far-off waters that divide present-day British Columbia from Alaska.

Advertisement

The rock near Elcho Harbour where Mackenzie and his men landed on July 21 is comparatively level ground when observed against the steep shores nearby. The travellers were glad to find this spot where they could take up a defensive position in case hostilities developed with the local inhabitants. Here, among the most important outcrops in human history, the explorer and his party felt vulnerable to unknown dangers. However, the local people arrived that evening not to attack but to trade. The Indigenous people brought a “very fine sea-otter skin” and a “beautifully white” goat skin to barter, demanding in exchange Mackenzie’s short sword, or hanger. But Mackenzie refused the bargain. Nevertheless, some trade was accomplished. Eventually, the traders left. Mackenzie instructed his men to keep watch by two in turn. Then he went to sleep for the night.

At eight o’clock the next morning, July 22, a clear sky happily presented itself. Now the supreme moment had arrived for eighteenth-century science. Mackenzie took out his instruments to begin the process of determining his exact location. He took five altitudes for time and, after making calculations, concluded that his chronometer was slow by one hour, twenty-one minutes, and forty-four seconds. He was then able to make adjustments for his previous mapping.

While Mackenzie was taking these astronomical measurements, two canoes arrived “with several men,” including the young chief who had accompanied Mackenzie since the Friendly Village but had briefly left the party to visit with local villagers. As the men set about bartering with Mackenzie’s voyageurs, MacKay, Mackenzie’s lieutenant, retrieved his burning-glass from his instruments bag. Before long he had lit a fire in the lid of his tobacco box. This so surprised the Indigenous observers that they traded their best sea-otter skin for the glass.

At this point the young chief, Mackenzie’s close acquaintance, urged him to leave, warning of enemies who “were as numerous as musquitoes, and of a very malignant character.” But Mackenzie had not yet completed the measurements necessary to pinpoint his latitude and longitude. “I was determined not to leave this place, except I was absolutely compelled to it, till I had ascertained its situation,” he wrote. He patiently took a meridian to verify his position. He needed to be sure he had the facts right.

While he was doing this, two “well-manned” canoes appeared. The young chief “renewed his entreaties for our departure, as they would soon come to shoot their arrows and hurl their spears at us.” Mackenzie declined to stir from his astronomical duties until he had accomplished his object. But he ordered his men to get their possessions into their canoe in preparation for speedy withdrawal. He calculated the latitude of the rocky islet as being close to what we now know it to be: fifty-two degrees, twenty-two minutes, thirty seconds north.

The two canoes approached and landed, but, instead of a party of warriors, “five men, with their families, landed very quietly from them,” Mackenzie wrote. “My instruments being exposed, they examined them with much apparent admiration and astonishment.”

With absolute determination Mackenzie completed his task. What he did next was an act of forethought. “I now mixed up some vermilion in melted grease, and inscribed, in large characters, on the South-East face of the rock on which we had slept last night, this brief memorial: “Alexander Mackenzie, from Canada, by land, the twenty-second of July, one thousand seven hundred and ninety-three.” Did anyone ever write such a pallid, laconic statement of accomplishment? It was merely a record of who, when, and where. The how and the why are absent from this statement of monumental attainment, whose significance echoes down through the years.

When Mackenzie came to write the account of his voyage, he explained the ever-so-brief window of opportunity he was afforded in achieving his scientific goal: “I had now determined my situation, which is the most fortunate circumstance of my long, painful, and perilous journey, as a few cloudy days would have prevented me from ascertaining the final longitude of it.” Now he had the geographical coordinates of the Pacific shore — handsome details indeed to include in his own copyrighted chart that appeared with his voyage account; handsome details, too, for the English cartographer Aaron Arrowsmith to include in his 1802 map of North America. In 1926 Canada’s Historic Sites and Monuments Board erected a monument and tablet to mark the terminus of the explorer’s passage. The famous inscription was carved in the rock and filled in with red concrete. Mackenzie’s rock is now the central feature of the Sir Alexander Mackenzie Provincial Park, which is accessible only by boat.

The return trip was physically and mentally exhausting. On Saturday, August 24, the party finally arrived at Fort Fork. “We threw out our flag, and accompanied it with a general discharge of our fire-arms; while the men were in such spirits, and made such an active use of their paddles, that we arrived before the two men whom we left here in the spring could recover their senses to answer us,” he wrote. “Here my voyages of discovery terminate. Their toils and their dangers, their solicitudes and sufferings, have not been exaggerated in my description. On the contrary, in many instances, language has failed me in the attempt to describe them. I received, however, the reward of my labours, for they were crowned with success.... I have now resumed the character of a trader.” Later that summer Mackenzie rejoined his Chipewyan wife, The Catt, and their young family at Fort Chipewyan. But he was fatigued and in ill health.

Mackenzie spent one more winter in the interior, cursing it. Then, with his star in the ascendant, he headed to Upper Canada to pay respects to Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe. He became an agent for many other traders, and Athabasca country became the new Eldorado of northwest North America, with its forests full of fur-bearing creatures. In later years Mackenzie became an articulate voice for Canadian commerce on the Pacific coast and across to China. He urged the British government to secure the inland trade for British subjects, for if it failed to do so, others would come and take it, and the national advantage gained by exploration would be lost. He never tired of bringing to the attention of government the necessity to nurture and protect trade, the lifeblood of empire, of profit and power. However, the path he traced from Fort Chipewyan to Elcho Bay was never developed into a commercial fur-trading route. Facing difficulties with the awkward transportation links in the north-central interior of what is now British Columbia, the North West Company reverted to its customary, less expensive ways of exporting furs, via Montreal and New York. Not until the Hudson’s Bay Company, three decades later, mastered the interior routes by using pack horses to circumvent the Fraser River rapids did the Canadian trade on the Pacific flourish and grow.

On reflection, we see how character and circumstance combine to make history. Mackenzie’s explorations were self-driven and were made possible by the grudging consent of his business partners, most of whom saw little advantage in geographical pursuits that did not yield financial reward. He expressed impatience with idleness, and he disliked solitude. An enthusiast for economic diversification, fishing, and whaling, Mackenzie was far ahead of his time in thinking about the possible evolution of western North America and of a Canadian gateway to the Pacific Ocean. He could see how the regions of Canada — the Pacific cordillera, the prairie basin, the Winnipeg nexus, the Great Lakes, and the St. Lawrence River — could be linked by trade. This was achieved in a different fashion by the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1885. Industrial technology of the age of rail and of steam navigation overcame the geographical obstacles that Mackenzie had faced and vividly described.

Mackenzie’s Voyages from Montreal on the River St. Lawrence through the Continent of North America to the Frozen and Pacific Oceans in the Years 1789 and 1793 was published in 1801. Why did it take seven years to get the work into print? In consequence of his arduous travels, Mackenzie suffered depression, major illness, and mental derangement. Dreams and visions kept him from completing his text; so did political interference. Aided by an editor, his work eventually reached the bookstalls and was an instant success. It has since become a classic of travel literature. As to the original journals upon which the book is based, only the record of Mackenzie’s voyage to the Arctic has survived in manuscript form.

We leave Mackenzie now, a bit breathless from the exhausting efforts of the passage he, his party, and their guides made through and over the mountains of the West. He never required more of his men than he did of himself; he led from the front. None of his party deserted. The outward journey from Fort Fork to the Pacific Ocean amounted to some 1,511 kilometres over seventy-four days. The return was more trying for a number of reasons, but he brought his whole expedition party safely and speedily home. His voyages of discovery foreshadowed a Canadian presence on the northwest coast, a rise that limited Russian progression southwards from Alaska, removed Spanish imperial ambitions and activities northwards from Mexico and California, and, in 1846, checked U.S. expansion by sea and land north of the forty-ninth parallel, leaving Vancouver Island in British, and later Canadian, hands and the continental realm under the same control.

We hope you will help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement