The Quickening Flavour

In the 1790s, the Hudson’s Bay Company faced a dilemma. Independent traders had circumvented the bayside trade and had set up posts on Lake Athabasca, some nine hundred kilometres inland from the coast of Hudson Bay, claiming the richest fur territory on the continent. To compete, the HBC would have to restructure its operations and move inland, finding new methods to address the logistics and costs of transporting trade items into the northwest interior and furs to the coast.

In preparing for this change, nothing was overlooked, including the question of how to preserve food. Salted meat and fowl formed a large part of the traders’ diet while the company was still based on the shores of Hudson Bay. Traders would receive their salt annually on supply ships from Britain. But, once the HBC decided to move inland, provisioning the company’s outposts with salt, an essential preservative, became more problematic.

Salt was heavy and bulky. Transporting it inland, whether by canoe or on foot, was economically inefficient in conditions where space and weight were at a premium. It therefore became essential for the fur traders to find local sources of salt, among many other resources, to supply their trading posts and to supplement the small amounts that could be transported inland from the bay. Fortunately, salt plains — saline environments fed by underground springs — are a natural phenomenon in the karst landscape surrounding Lake Athabasca and the nearby Slave River, in what is now northeastern Alberta. The springs carry the mineral from subterranean deposits. At the surface, the water pools and evaporates, leaving behind an accumulation of salt.

The earliest recorded reference to salt deposits in the Slave River area is the Moses Norton map of 1760. From 1762 to 1773 Norton was the Chief Factor at the HBC’s Prince of Wales Fort on Hudson Bay near present-day Churchill, Manitoba. He based his map on information from Dene traders who had travelled a thousand kilometres overland from the Slave River area to the fort. Norton’s map is a gathering of information about a very distant land, including a reference to salt in the Lake Athabasca area.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

It wasn’t until nearly thirty years later that explorers visited and noted the salt deposits in this area. The salt deposit near Darough Creek, a tributary of the Slave River, is the first one known to have been seen by Canadians of European descent and appears on a map in Alexander Mackenzie’s published journal of his 1789 trip to the Arctic Ocean and his 1793 overland trek to the Pacific coast. Mackenzie was a fur trader employed by the North West Company and was based on Lake Athabasca. Mackenzie’s map identifies “Salt Springs” on the west side of the Slave River, near a set of rapids.

Mackenzie wrote that salt was present in the country and that it was used as an article of trade by Indigenous traders. Bemoaning the staple diet of whitefish and pemmican for North West Company traders on Lake Athabasca, Mackenzie wrote: “Thus do the voyageurs live, year after year, entirely upon fish, without even the quickening flavour of salt, or the variety of any farinaceous root or vegetable. Salt, however, if their habits had not rendered it unnecessary, might be obtained in this country to the Westward of the Peace River, where it loses its name in that of the Slave River, from the numerous salt-ponds and springs to be found there, which will supply in any quantity, in a state of concretion, and perfectly white and clean. When the Indians pass that way they bring a small quantity to the fort, with other articles of traffic.”

From 1790 to 1792, HBC surveyor Philip Turnor and map-maker and fur trader Peter Fidler travelled to Lake Athabasca to assess the work of independent traders and the potential for an HBC trading post. Fidler returned to Lake Athabasca in 1802 to establish a presence for the Hudson’s Bay Company. He founded Nottingham House before leaving the area in 1806. Turnor and Fidler’s arrival provides historians with the first detailed documenting of salt and its use in the Lake Athabasca trade.

Fidler visited the Darough Creek deposit on a trip down the Slave River in July 1791. This, he noted, was “where the Indians get the Salt from that is to be had in such quantities and in a very pure state about 6 miles up the Creek.” His journal continued: “They find it in hillocks and they say that when they have taken a good quantity from the top of one of these hillocks & made a kind of an hollow the next year it will again be quite filled up with as pure fine white Salt as before.”

Advertisement

Other than as an item of trade, little is yet known of the particular uses of salt by Indigenous peoples. We do know that salt was used by fur traders as a condiment and for preserving some foods. Turnor wrote in his journal on July 6, 1791, that he had “used of it and have eat meat cured with it and think it very good.” This is the first reference we have to the use of salt for preserving meat in the Athabasca region.

In his final journal entries before leaving Lake Athabasca, Turnor summarized the existing resource potential to support the Athabasca trade. Among other things, Turnor noted, “this lake is an exceeding fine place for Geese in the fall of the year at which time great numbers might be cured for the winter as they are then killed setting as they come to the sands at the rate of two or three at a shot. And they keep flying backwards and forwards the whole day as there is no tide to cover the sands. And that material article salt is very plenty at this place, the Indians bringing great quantities of it which they trade at a very easy rate.”

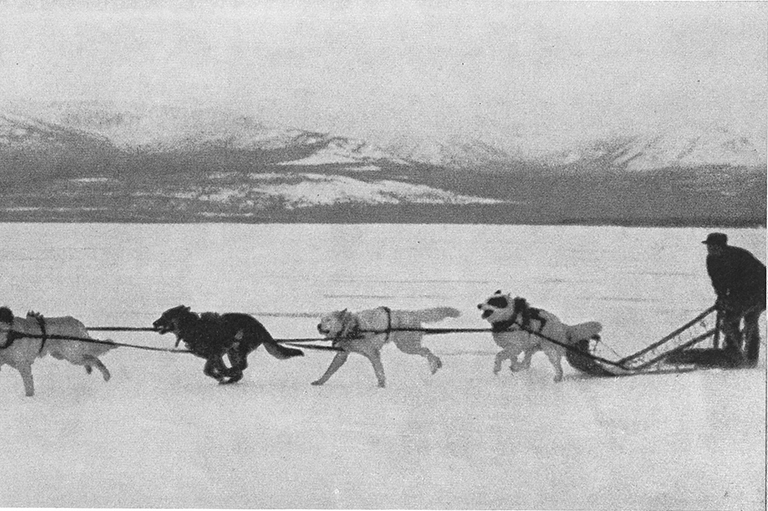

We get further information about the use of salt from Fidler’s 1803–05 Nottingham House post journals. Fidler was in charge of the post, which was the first official trading venture of the Hudson’s Bay Company on Lake Athabasca. He clarified that the HBC traders did not rely entirely on trade to provide them with salt; they also collected salt to supplement the small supply they brought inland from the HBC post on Hudson Bay. On Tuesday, October 23, 1804, Fidler wrote: “William Henry & Courtney went away down Slave river in 2 Canoes to where the Salt is found above the rapids.”

As a preservative, salt was primarily used for salting ducks and geese. There are several references in Fidler’s journal to “salting a keg of geese.” Salted fowl appears to have been a treat, as on December 28, 1803, it was recorded that the men posted at the fishing nets received, along with some rum and turnips, “1 ½ Salt Geese and a bit of fresh and a bit of dry meat.” For a New Year’s treat in 1804, the fisherman received “3 Salt geese — 2 ducks 30 lbs of Dry Meat 1 bladder of fatt 15 lb of fresh meat — ¼ Chocolate & ½ of Tea — 1.2 of Spices — 6 rabbits, 6 partridges & 2 lb of bacon also about 4 [gallons] of turnip & Potatoes 1 Quart high spirit & 1 pint of rum & 1 quart of butter.”

Red meat — or fresh meat, as it is called in the journals — was primarily moose or bison and was not commonly salted. It would be kept frozen if procured during the winter, although, being unsalted, there was always the chance of it going bad. “1803 November 1. Washed the little fresh meat we have as it was become mouldy,” Fidler’s journal recorded. The fact that Fidler made only one reference to salted red meat suggested that it was more a delicacy than a staple part of the diet: “1804, September 27, Thursday.... Salted a keg of Moosemeat. Ribs. Belly Piece — and the meat of the rump.” Red meat was most commonly dried or beaten and mixed into pemmican, both of which were more effective means of preservation and reduced the weight of the meat for travel when it was being supplied by Indigenous traders.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Fidler’s Nottingham House journal provides a glimpse into the HBC’s adaptation to a business model based on inland trading posts. Procuring the resources necessary to support the post — through trade and through the efforts of post employees — and limiting the amount and cost of provisions to be imported would be key to the company’s economic success. Unfortunately, inland trade initially proved too competitive for the Hudson’s Bay Company, and it wasn’t until its amalgamation with the North West Company in 1821 that the HBC was able to exert control over Lake Athabasca and expand its reach further north into the Mackenzie region.

A prelude to this expansion is a sketch on the end board of Fidler’s 1803–05 Nottingham House journal. The drawing shows an extensive salt deposit on the Salt River, downriver from the rapids on the Slave River. These deposits were known to Indigenous peoples. Oral history tells us the Dene would travel three hundred kilometres from Yellowknife to collect salt, then return six hundred kilometres north to Contwoyto Lake in modern-day Nunavut, where they would trade it with the Inuit. These deposits later became the primary salt source for northern trade and early settlement, control being transferred by the HBC to the Métis patriarch François Beaulieu in the 1840s when he established the community of Salt River, in what is now the Northwest Territories. The valuable deposits later became part of the Roman Catholic mission operations based in Fort Smith, Northwest Territories.

Late nineteenth-century efforts by the Canadian government to increase settlement on the prairies led to the development of industrial salt mining in the south that proved, ultimately, a more economical and productive way to serve the Western Canadian market. Transportation infrastructure eventually developed to supply the southern product to settlements in the North. The deposits on the Slave River, once again on the periphery of the nation’s consciousness, reverted to their status as geological anomalies in what is now Wood Buffalo National Park.

Advertisement

Rock of Ages

There is an old folk tale in which a king asks his three daughters how much they love him. The two eldest reply, “as much as bread” and “as much as wine.” The youngest replies, “as much as salt.” She is banished for her rudeness — that is, until later in the story, when the king is given a saltless meal. Despising the bland food, he finally recognizes the value of his youngest daughter’s love.

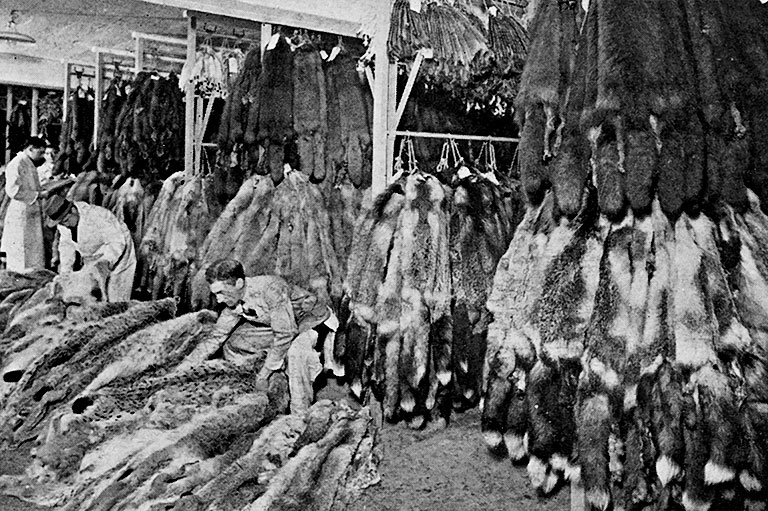

Humans need salt to survive. Throughout history salt has been a medicine and a condiment, and it may also have served spiritual purposes. With the emergence of sedentary populations and the advent of animal husbandry and agriculture, salt acquired a renewed purpose as a preservative for meats, fish, cheese, and vegetables.

When raw meat is coated with coarse salt, the salt draws the moisture out of the meat, leaving it dehydrated and limiting the environment in which harmful bacteria can grow. Because salted meat can be stored for future use, it created food surpluses that became the foundation of powerful empires. From the twelfth through the fourteenth centuries, Venice built an international economy based on a monopoly on the production and trade of salt throughout the Mediterranean.

In the fifteenth century, European fishermen began fishing for cod in the waters surrounding Newfoundland. They salted the fish to preserve it for transport and for sale in Europe. The salt-cod fishery remained a mainstay of the island’s economy through the nineteenth century.

When the British ruled India, the Salt Act of 1882 prohibited Indians from collecting or selling salt, instead forcing them to buy it from their British rulers and imposing an onerous salt tax. In an act of civil disobedience in 1930, Mohandas Gandhi led thousands of Indians on a march to the coastal town of Dandi on the Arabian Sea to collect salt from sea water, defying the British law and fanning the flames of the Indian independence movement. — Patrick Carroll.

We hope you will help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement