Golden Opportunity

What drew you and Arn to devote so many years to researching Giant Mine?

We both started out looking at abandoned mines more broadly. Arn had studied uranium mining in Saskatchewan, and I had lived in the Northwest Territories. Giant Mine stood out because of its scale: enough arsenic trioxide left behind to poison the planet four times over. It’s arguably Canada’s most contaminated site, and we felt someone had to tell the history of this place.

You foreground Yellowknives Dene voices in the book. How did you approach that history?

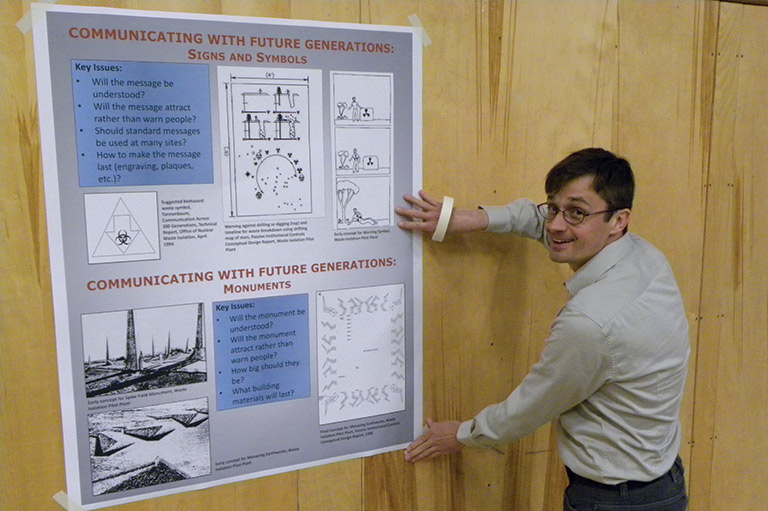

With community partners, we documented areas affected by arsenicpollution, supported mapping projects with Dene Elders, collaborated on a documentary [Guardians of Eternity] and worked with the community to think about how to communicate toxic hazards to future generations. The book reflects those relationships while also acknowledging that Indigenous communities are not just victims — they have consistently shaped the debate and resisted.

Were there any perspectives that challenged your thinking as historians?

At first, some mining heritage advocates were skeptical of our work. Over time, dialogue grew and we realized the story of Giant Mine couldn’t erase the pride many workers felt in building Yellowknife.

Mining communities often hold two truths: the industry caused harm, yet people remain proud of their skills and labour. What’s remarkable at Giant Mine is how unions and Indigenous activists found common cause, recognizing that both workers and communities were on the front lines of pollution.

What was your research process like?

The process stretched over nearly 15 years. We dug into territorial and federal archives, newspapers and government water board records. Oral histories were invaluable, as were collections from local activists like Kevin O’Reilly, who had amassed thousands of documents. Taking the time to let sources surface meant we uncovered overlooked perspectives, including transcripts of public hearings where Indigenous and settler residents spoke powerfully about pollution and accountability.

What do Canadians misunderstand about the Giant Mine hazard?

Many people know something about Giant Mine, but the moral dimension is often overlooked. It forces us to confront the costs of short-term thinking. The cleanup alone is projected at $4.3 billion — more money than the mine ever made. And that’s just the start; maintaining frozen arsenic trioxide underground for centuries or developing new technology to remove it will cost much more. Giant Mine reminds us that what looks like nation-building today can become an enormous liability tomorrow.

In your book, you look beyond the environmental disaster. Are there moments of resistance and recovery that stood out to you?

By the 1970s, the Dene were voicing strong anti-colonial critiques, publishing their own studies and joining forces with labour unions. Their activism brought national attention to the arsenic crisis and forced improvements in pollution controls. That resistance has continued: when the federal government proposed a “freeze it forever” plan, local leaders demanded a full environmental assessment. The result was a binding agreement that committed Ottawa to eventually removing the arsenic trioxide and created an independent oversight board to hold the project accountable.

Do you see the book as a cautionary tale?

Absolutely. Giant Mine shows the dangers of producing hyper-abundant materials without considering the long-term costs. Gold, ironically, isn’t even essential — yet, its pursuit left behind staggering environmental damage.

The lesson is that development projects must plan for their aftermath, not leave future generations to shoulder the burden.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement