The World's Oldest Multinational

What is the secret of corporate longevity? In 2004, an article in the Economist magazine came up with some answers, and, although its list was for family companies, the same ideas can probably be applied to corporations. The first factor was possession of a reservoir of trust, pride, and money; the second was an ability to evolve; and the third was a good grasp of the firm’s core competence. Without doubt there also has to be a little bit of serendipity or good old-fashioned luck.

On May 2, 2020, Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), the oldest continuously operating trading company in the world, turns 350. It has already outlived the Honourable East India Company by nearly a century. How did HBC survive so long? All three success factors have come into play over its storied history.

In the beginning, The Governor and Company of Adventurers of England trading into Hudson Bay had a corporate head office and customers in Great Britain and Europe and fur-trading operations in northern Canada. After two hundred years, as the fur trade declined, the Company shifted its business to a combination of retail and real estate in Canada. But it would take another century before the head office was moved from Britain to Canada in recognition of the Company’s tricentennial. Ownership shifted as well. In 2006 HBC was sold to Americans for the first time, but the corporate head office has remained in Canada. Retail and real estate have become North American businesses, rather than being limited to Canada.

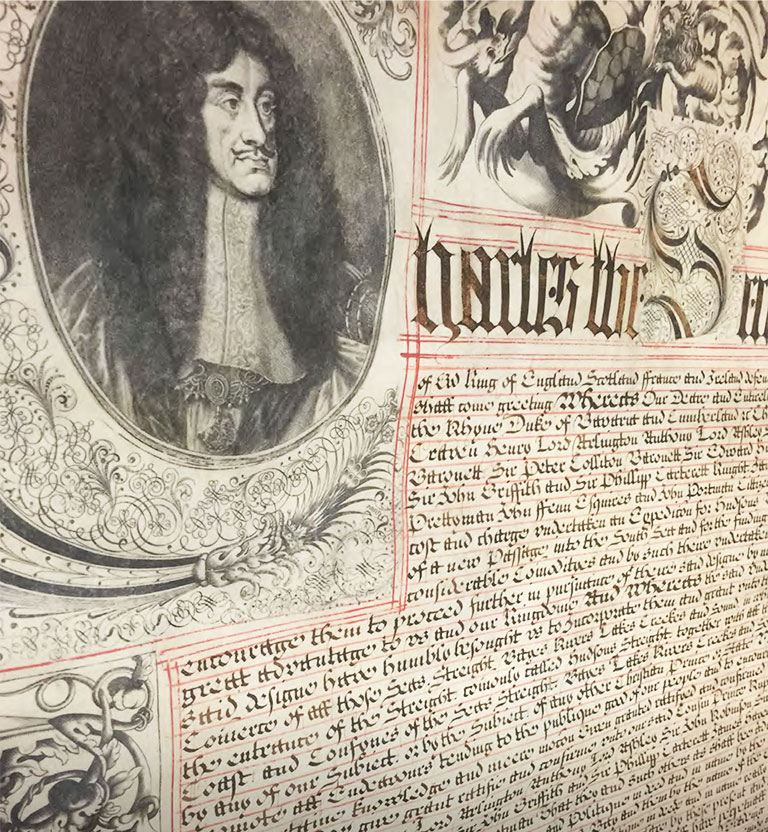

As every Canadian schoolchild once knew, Hudson’s Bay Company was created by a happy convergence of two disaffected French-Canadian coureurs de bois and a group of courtiers in the recently restored Stuart royal court of King Charles II. What fewer people know is that the company was a product of the prevailing economic theory of the day, mercantilism. According to mercantilist theory, nations had to be self-sufficient. This made colonies important as sources of raw resources to be exported back to the ruling country.

The key method of creating colonies was through royal chartered companies that had limited liability — an assurance that corporate losses would not exceed invested capital — and that had specific geographic areas in which to trade. This was true not only in Great Britain but also through- out Europe. Hudson’s Bay Company’s charter permitted HBC to explore for the Northwest Passage and to trade in furs. Its principal role was to provide goods for England, specifically beaver pelts for the hat-making industry and for re-export to continental European cities.

In its 350 years the Company has faced at least five major challenges that would likely have destroyed other companies: the threat from the Montreal “pedlars” of the North West Company in the late-eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries; the question of what to do with the money and land HBC received when it sold Rupert’s Land to the Dominion of Canada in 1870; the conflicted style of operation of Lord Strathcona, governor of the Company from 1889 to 1914; the economic downturn of the early 1980s; and the “clicks and mortar” debate of the twenty-first century.

In the Company’s first four-plus decades its major challenge came from the French. HBC’s response was to survive, but not at any cost.

With the French competition eliminated by the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, the next half century was both peaceful and profitable. The Company expected First Nations to bring their furs to its posts on Hudson and James bays, leading some to dismiss it as being “asleep by the frozen sea.” That complacent attitude changed when what first appeared as a blessing to the Company turned out to be an even bigger challenge than it had faced from the French.

After the British defeated the French in the Seven Years War (known in the United States as the French and Indian War), non-French — mostly Scottish — fur traders based in Montreal made their way west to trade with First Nations, obtaining furs before Indigenous traders could get to a Company post on Hudson Bay. These traders were dismissively called “pedlars,” but they created their own fur-trading companies, the strongest of which was the North West Company.

The Montreal traders were more entrepreneurial and aggressive than their HBC rivals — it seemed the Nor’Westers were always a few steps or posts ahead. In 1790, when HBC finally entered the Athabasca country a thousand kilometres north of what is now Churchill, Manitoba, it was not well-prepared.

The first two decades of the nineteenth century saw fur trade rivalry erupt into open warfare. If HBC was to survive, it had to change. Fortunately there were new voices on the Company’s governing committee. Lord Selkirk, a Scottish nobleman, and some of his allies, including his brother-in-law Andrew Wedderburn, started buying up HBC stock. By 1808 Wedderburn had a place on the governing committee and an impact on managerial decisions. Wedderburn submitted a plan to combat the Company’s financial problems. It included a dramatic change in personnel policies, moving away from hiring quiet Orkneymen toward the recruitment of Scottish highlanders and former Nor’Westers who were prepared to use force against force.

Serious clashes occurred. In 1816 alone, the number of fur traders and farmers killed by starvation or open battle was sufficient to cause Britain to issue a royal proclamation against “open warfare in the Indian territories.” Three years later, Lord Bathurst, Britain’s Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, sent a letter to the heads of the two companies demanding that the rivalry be ended and the peace be kept. In response, the two companies merged in 1821.

The merger was followed by years of good financial results under the executive leadership of George Simpson, one of the outstanding business executives in mid-nine-teenth-century Canada.

Yet by the 1860s the fur trade was in steep decline. In addition, there were attacks on the Company’s monopoly by Métis traders in the Red River region, as well as a growing desire for western expansion by George Brown and other politicians back east, who aimed to keep the country British. As a consequence, late in 1869 HBC signed a deed of surrender turning the Rupert’s Land territory over to Canada in exchange for £300,000, one twentieth of all the fertile land in Rupert’s Land, lands around each of HBC’s posts, and the right to continue to trade, albeit without a monopoly provision. In 1870 the agreement received royal assent.

Now HBC had a new challenge: what to do with the cash and land received from the sale. The Company could have gone into farming, ranching, lumbering, fishing, and mining, or it might even have built a railway. Initially the Company chose retail operations and land sales.

Why retail? Why choose to move from a monopoly-protected fur trade to what is probably the most competitive industry of all? Can a fur-trading post become a department store with just a few cosmetic changes, or would the transition require significant capital spending?

And why not build a railway? The Union Pacific Railroad had just been completed, and the Canadian Pacific Railway was only a gleam in one or two people’s eyes. Why didn’t HBC leadership in London see the opportunity? This is not an easy question to answer, but to start one must turn to Donald Smith, later Lord Strathcona.

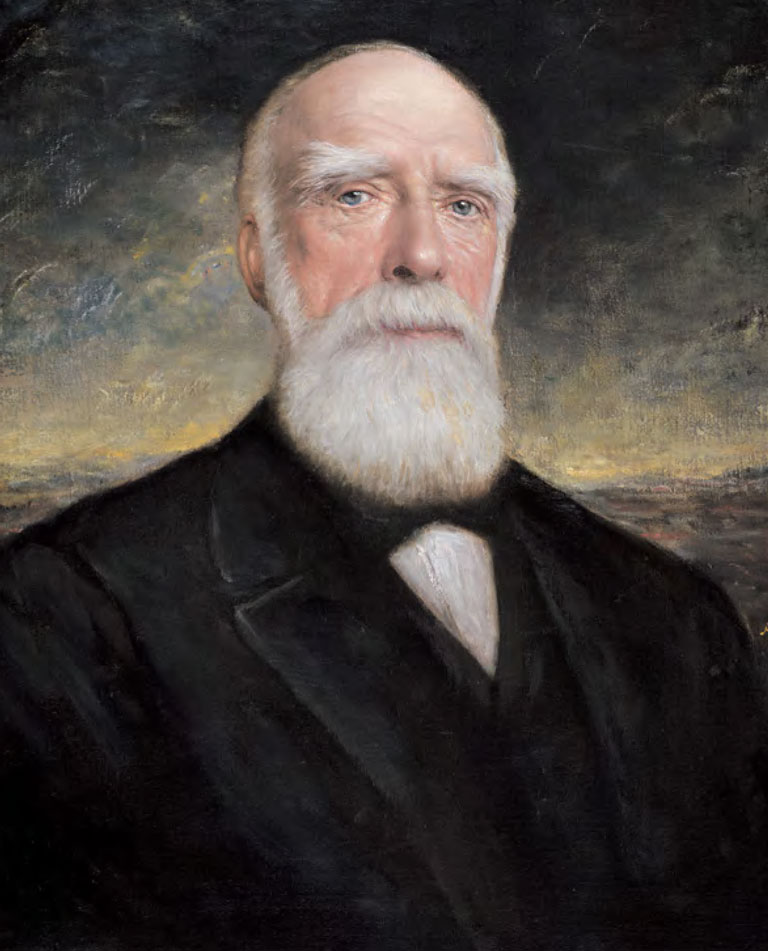

As a teenager, Smith came to Labrador at the bottom of the HBC hierarchy. He remained in Labrador for thirty years before moving to Montreal in 1868 as commissioner of the eastern region. In 1879 he resigned from HBC, but he continued to invest in Company stock as well as in the Bank of Montreal and, more importantly, in railways located in both Canada and the United States.

In 1889 Smith returned to Hudson’s Bay Company, this time as principal shareholder and the first Canadian governor, a position he held until his death in 1914. One of his successes was to restrain land sales until the twentieth century, when the Canadian wheat boom began and land prices skyrocketed. From 1905 to 1914, the Company’s annual dividends ranged from a low of twenty-nine per cent to a high of fifty per cent.

In spite of these achievements, Lord Strathcona presented a challenge to the Company because of his love for himself: That is, he placed his own ambitions ahead of those of the Company. New governing committee members took action to reorganize the Company’s retail operations, providing £1 million for capital investment in its stores, creating a Canadian advisory committee based in Winnipeg, and establishing modern department stores across Western Canada.

The Company did not move into eastern Canada until 1960, when it acquired Henry Morgan & Co., a well-established Montreal-based chain of department stores. During the 1960s, HBC increased its capital and paid excellent dividends, but the Company was losing ground in the Canadian retail sector. The British board was prepared to consider moving the head office from London to Winnipeg, but not until a competent retailer was running the show. The response from The Bay — as the department store chain was then known — was to lure Don McGiverin, an outstanding retailer, away from Eaton’s in 1969. The next year, on the three-hundredth anniversary of the incorporation of Hudson’s Bay Company, its head office was moved to Winnipeg.

McGiverin lit a fire under the organization, first moving the head office again, this time, in 1974, to the heart of corporate Canada in Toronto, where the Company built a thirty-five-storey office tower. Under McGiverin’s leadership The Bay went on the acquisition trail, acquiring Zellers, a discount chain, and Simpsons, a Toronto-based department store chain.

The 1970s were unbelievably good for HBC, financially speaking. At the end of the decade Ken Thomson, son of Lord Roy Thomson and Canada’s richest person, acquired seventy-five per cent of the Company.

-

A Hudson's Bay Company delivery man stands beside his team of horses in Vancouver in 1906.HBC Archives

A Hudson's Bay Company delivery man stands beside his team of horses in Vancouver in 1906.HBC Archives -

An HBC employee works the pharmacy counter at the Winnipeg store in 1937.HBC Archives

An HBC employee works the pharmacy counter at the Winnipeg store in 1937.HBC Archives -

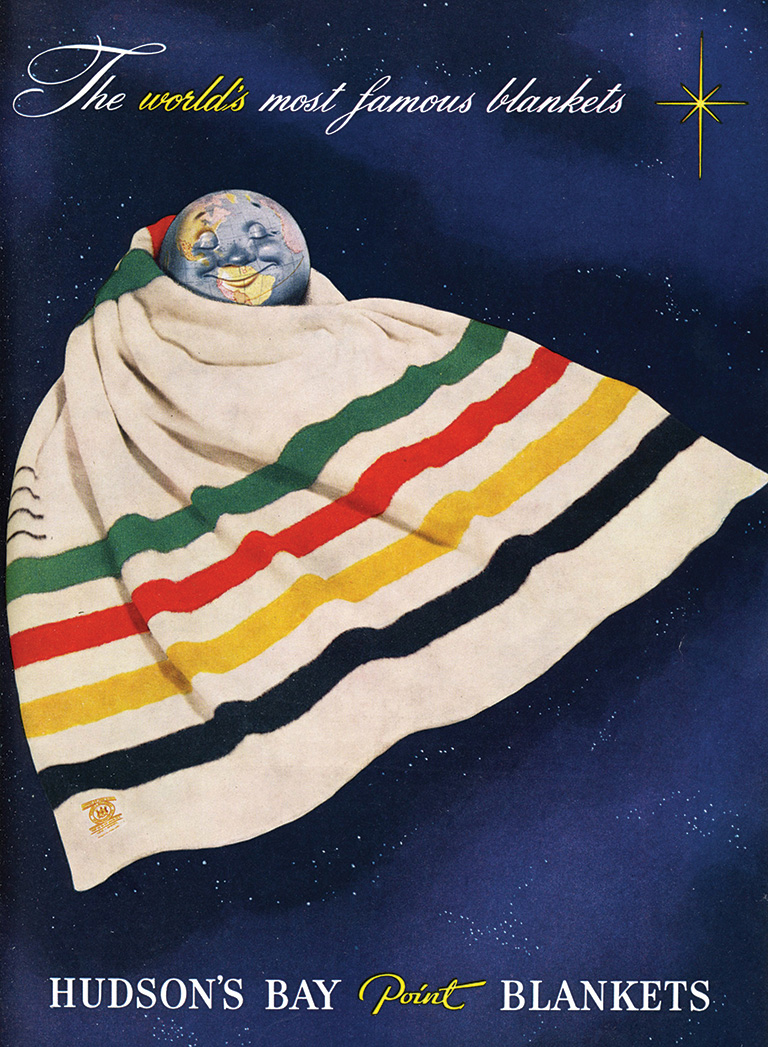

A 1939 brochure for Hudson's Bay blankets and blanket coats displays a selection of items including coats and mitts, hunting caps for men, and cadet caps for women.HBC Archives

A 1939 brochure for Hudson's Bay blankets and blanket coats displays a selection of items including coats and mitts, hunting caps for men, and cadet caps for women.HBC Archives -

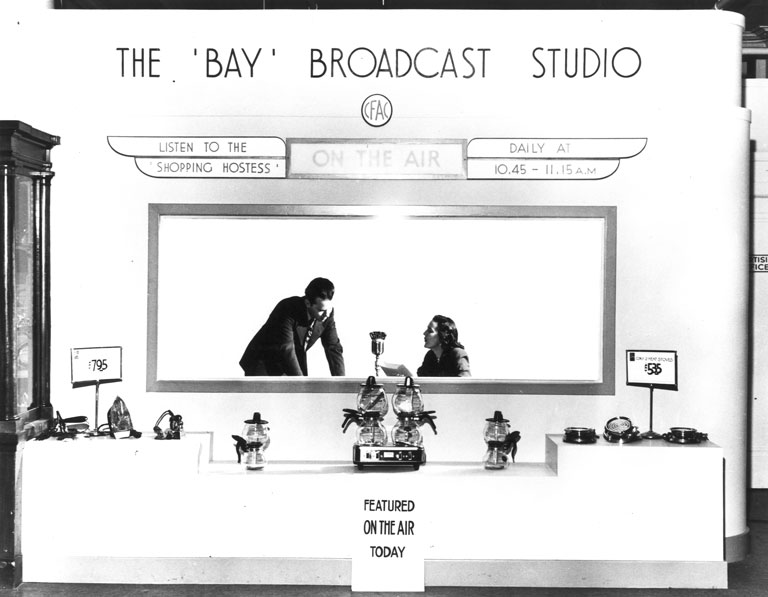

A sign alerts shoppers that HBC announcers are "on the air" during a 1940 broadcast from the Bay Broadcast Studio, located in the Calgary HBC store.HBC Archives

A sign alerts shoppers that HBC announcers are "on the air" during a 1940 broadcast from the Bay Broadcast Studio, located in the Calgary HBC store.HBC Archives -

This department store in downtown Calgary, shown in 2015, opened in 1913 as one of six flagship Hudson's Bay locations.HBC Archives

This department store in downtown Calgary, shown in 2015, opened in 1913 as one of six flagship Hudson's Bay locations.HBC Archives

Then came the challenging 1980s. In contrast to its previously conservative approach, the acquisition of other retailers left The Bay financially exposed. In 1984 Thomson ordered a drastic change in management direction. McGiverin resigned the next year but remained as governor. The new management sold off the fur-trading and wholesale divisions as well as the Northern Stores, HBC’s trading posts in northern Canada. The Company was rewarded in 1989 with the first profit it had seen in nearly ten years.

The twenty-first century brought “the creative-destructive power of capitalism” — the process by which business is constantly shedding the old and replacing it with the new — to the retail sector, particularly to large department stores. Not only did the Internet provide new challenges such as mega-retailer Amazon, but the model of the department store as anchor tenant in a shopping mall became passé as online shopping revolutionized the retail sector. It also became readily apparent that retail was no longer a domestic enterprise, as Walmart, Costco, Home Depot, and other retailers entered the Canadian market.

The 2000s saw ownership changes at HBC. In 2006, for the first time in 336 years, the Company was acquired by an American, Jerry Zucker, who took it private. Two years later, Zucker died, and the Company was purchased by NRDC Equity Partners, an American private-equity firm owned by the Baker family, who were also owners of Lord & Taylor, an American luxury department store.

After NRDC took the Company public again in 2012, it acquired American luxury retailer Saks, Inc., operator of luxury department store Saks Fifth Avenue and its discount Saks OFF 5TH franchise. As of press time, HBC is in the process of going private to allow it to regroup and to improve operations.

Hudson’s Bay Company has faced many challenges in its first 350 years. This article has identified five of the major ones. But the Company is now facing as significant a challenge as it has experienced since the demise of the fur-trading business in the latter part of the nineteenth century.

In 2020 the challenge is the decline of the department store, as online-first companies dominate the retail fray. Clicks and mortar, a combination of online and in-store shopping, is the new reality. As The Bay goes private it will have the opportunity to reflect on what should be the next direction for this 350-year-old Company of Adventurers.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Beautiful woven all-silk bow tie — burgundy with small silver beaver images throughout. This bow tie was inspired by Pierre Berton, inaugural winner of the Governor General's History Award for Popular Media: The Pierre Berton Award, presented by Canada's History Society. Self-tie with adjustments for neck size. Please note: these are not pre-tied.

Made exclusively for Canada's History.