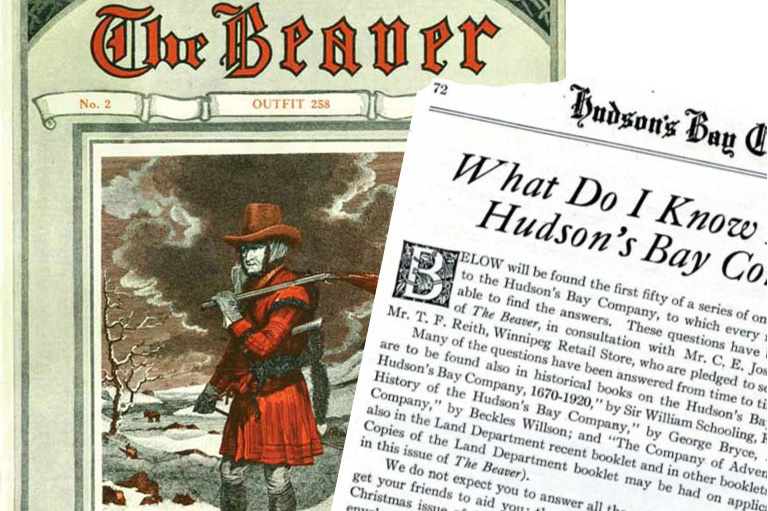

Charting a Course

The two men looked silently at each other and then embraced. Both Pierre-Esprit Radisson and his brother-in-law Médard Chouart, Sieur Des Groseilliers, knew that the mission upon which they were about to embark was fraught with danger.

It was June 5, 1668, and the pair of French fur traders were at the dockyards in London, England, making the final preparations for a months-long sea voyage. Their plan was to sail directly into the heart of North America via the mysterious “Inland Sea” visited in 1610 by the English explorer Henry Hudson. Once there, they hoped to launch a new fur-trading business based out of Hudson Bay that would circumvent the French fur traders who operated out of Montreal. At the time, New France dominated the fur trade in the region around the St. Lawrence River.

This would be no easy cruise down the River Thames. Crossing the Atlantic Ocean in the seventeenth century was a perilous undertaking filled with many threats, including ocean storms, disease outbreaks, and even pirates.

As the Frenchmen headed to their ships — Eaglet and Nonsuch — their minds likely wandered back to that moment, two years earlier, when they had arrived in England to pitch their plan to a gathering of wealthy investors and nobles.

There had been no guarantee that the investors would support their scheme. After all, Radisson and Des Groseilliers had already pitched the same plan to two other groups, one in France and one in New England, and on both occasions they were turned down. And now here they were — “Mr. Radishes and Mr. Gooseberries,” as they were known to their English backers — about to set sail on ships loaded with trade goods, heading west.

Unfortunately, almost as soon as their adventure began, disaster struck. Barely two months into their voyage, Eaglet, carrying Radisson, was beset by a terrible storm. “Wee went together 400 leagues from ye North of Ireland, where a sudden great storme did rise & put us asunder,” Radisson later wrote in his journal. “The sea was soe furious 6 or 7 hours after that it did almost overturne our ship, so that wee were forced to cut our masts.”

Eaglet limped back into port at Plymouth, on the south coast of England — a disastrous turn of events. The English investors, who included Prince Rupert of the Rhine, the cousin of King Charles II of England, demanded to know the status of the second ship, Nonsuch, which carried Des Groseilliers. All Radisson knew was that Nonsuch had escaped the storm and had kept going.

Months passed, filled with waiting and worry. Had Nonsuch sank in a storm? Was it trapped in sea ice? Was the crew shipwrecked and starving on the stark shores of Hudson Bay? A year and a half passed with no word. A pall of despair hung over the mission.

But in October 1669, sixteen months after Nonsuch’s departure, the ship was spied sailing up the River Thames into the heart of London. Riding low in the water, the ship was heavy with more than three thousand pounds of beaver pelts. The audacious plan had worked. Des Groseilliers and Radisson were celebrated as heroes. And from this initial triumph Hudson’s Bay Company was born.

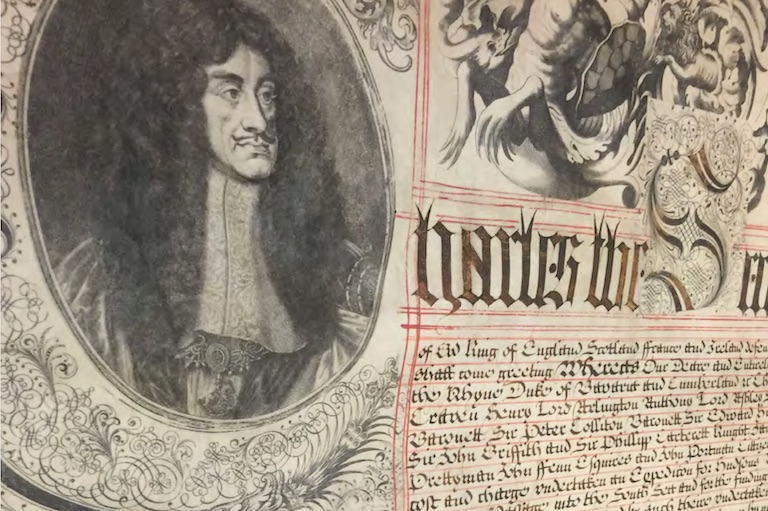

Thanks to the success of the Nonsuch expedition, on May 2, 1670, King Charles II granted HBC a Royal Charter that gave it exclusive trading rights over the huge territory named Rupert’s Land. “The Governor and Company of Adventurers of England trading into Hudson Bay” would go on to play a defining role in shaping North America.

THE ROYAL CHARTER

The Royal Charter gave “the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England trading into Hudson Bay” a trading monopoly over the Hudson Bay drainage basin.

Its clauses outline the rights and obligations of the Company of Adventurers over its new domain, including the right to exploit mineral resources and the obligation to search for the Northwest Passage.

The document also detailed how the Company would be governed. The King named his “dear and entirely beloved cousin” Prince Rupert as the Company’s first governor of the territory that would henceforth be known as “Rupert’s Land.”

Today, the original Royal Charter is preserved in HBC’s corporate office in Toronto.

The fur trade would also forever transform existing Indigenous trade relationships that had evolved over millennia. Long before the first Europeans set foot in the Americas, Indigenous peoples had developed cultures and traditions that suited the environments in which they lived. They created tools, honed their innovations, and then passed their skills and knowledge to their children and grandchildren. They also forged trade relationships with other Indigenous nations that were based on respect, mutual benefit, and honest communication.

Europeans also had complicated systems of trading, typically based on profit. And they placed high value on precious metals and minerals.

In North America, early European explorers hoped to strike it rich but were frustrated by their failure to find mountains of gold and jewels. It didn’t take long, however, for them to realize that North America abounded with natural resources, including furs, that could be sold for profit back home.

Indigenous and non-Indigenous people had different ways of thinking about furs. Indigenous peoples valued animal furs and hides for their use in making shelters and for clothing. For many Europeans, especially in the seventeenth century, fur was a fashion statement.

Beaver fur was especially prized, because it could be turned into high-quality felt and used to make expensive hats. Thanks to the popularity of beaver hats, the animal had been all but hunted to extinction in western Europe. When Europeans heard about the plentiful populations of beavers and other fur-bearing animals in North America, they felt they had found a virtual gold mine.

Prior to Nonsuch’s voyage to Hudson Bay, Des Groseilliers and Radisson spent time working as fur traders in New France — the historic French territory that was centred around Quebec. It was during this time that they learned of the rich furs in the Hudson Bay region. Thus, the mission to the bay was the culmination of a dream for Des Groseilliers.

After the storm forced Eaglet to turn back, Des Groseilliers continued aboard Nonsuch, retracing Henry Hudson’s steps through the frigid waters of the southern Arctic, down through Hudson Bay, and finally into James Bay.

Nonsuch was captained by Zachariah Gillam of Boston, who kept a detailed log of the voyage. In it he wrote of seeing icebergs (“20 Islands of Ice”) and polar bears and of going ashore at islands along the way only to find them deserted.

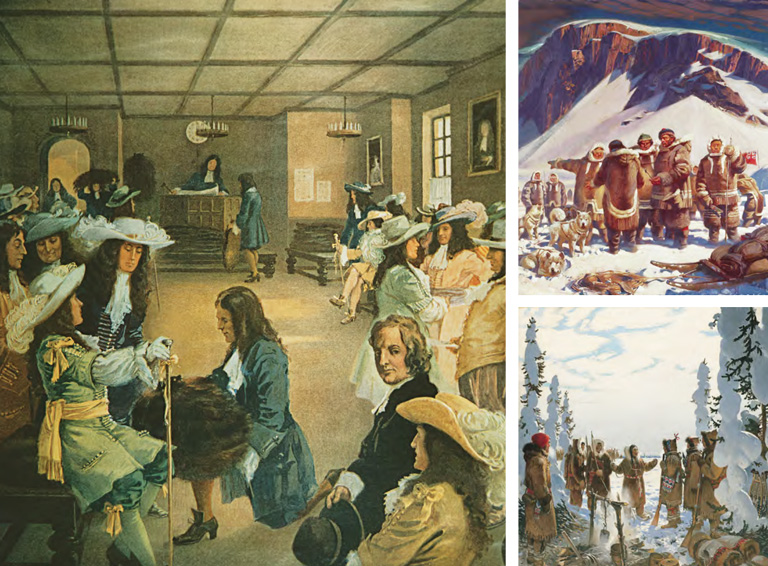

On September 22, 1668, he spotted smoke rising from the mainland. Ordering a crew member to fire a musket in the air as a salute, he brought Nonsuch to a halt and waited. Soon several Cree men appeared, and the two groups briefly traded. The Cree suggested that Gillam and his crew continue on to a nearby inlet, where a larger Cree community was located.

On September 29, with ice setting in and winter looming, the Europeans found a spot at the mouth of the Rupert River where they could build a place — Charles Fort — to spend the winter. They soon met more Cree people living near modern-day Waskaganish, Quebec. Des Groseilliers established a League of Friendship with the Cree, during which the Frenchman, according to Gillam, “formally purchased” the surrounding land.

Gillam later described the Cree community to the Royal Society in England: “The people ... using bows and arrows, living in tents, wch they remove from one place to another, according to the seasons of hunting, fowling, fishing. As for their meat, they live on venison, wild foule, as geese, partridges, and rabbats, wch both are as white as snow, and of wch there is great abundance.”

In the spring, about three hundred Cree travelled to Charles Fort to trade furs in exchange for European items such as kettles, metal tools, needles, beads, and blankets. Des Groseilliers was astounded at the high quality of the beaver pelts — the cold temperatures caused the furs to be especially lush and lustrous.

This first exchange between HBC and the Cree was the beginning of a commercial enterprise that would profoundly change the lives of Indigenous peoples throughout North America.

In 1670, two vessels, Prince Rupert and Wivenhoe, carried Radisson, Des Groseilliers, and a contingent of HBC traders back to Hudson Bay. The HBC traders exchanged items with the Cree and began building shelter for the winter. The Cree helped to supply the fort with meat and other provisions, but some of the Europeans nonetheless fell ill with scurvy.

In October 1671, the HBC traders returned to England with their ships filled with furs. And on January 24, 1672, HBC held its first public auction of furs, with Prince Rupert in attendance, at Garraway’s Coffee House in London.

Over the course of the next few years, HBC expanded its network of forts in the bay region. The Company’s business plan called for its traders to remain at forts built around the bay while their Indigenous trading partners headed inland to trap fur-bearing animals. In the spring the trappers would return to HBC forts to trade their pelts for European goods. While beaver fur was the most prized, Indigenous people also traded the pelts of otter, muskrat, mink, fox, raccoon, deer, moose, and bear. In addition to trapping, Indigenous men and women often worked around HBC’s forts, supplying provisions such as meat and fish and helping to haul furs.

One of the earliest women to play a leading role in the fur trade was Thanadelthur, a Dene-speaking Chipewyan woman. Thanadelthur was born sometime around 1697 in what is now northern Manitoba. In 1713, the Cree attacked the Chipewyans. Thanadelthur and a few others were subsequently captured. After spending a year in captivity, Thanadelthur escaped. Cold and hungry, she was discovered by hunters who worked at HBC’s York Factory. In late 1714, the hunting party arrived back at York Factory and introduced Thanadelthur to HBC Chief Factor James Knight.

Hostilities between the Cree and the Chipewyan peoples were bad for business, so Knight asked Thanadelthur to use her connections to try to end the fighting. In June 1715, Thanadelthur, accompanied by an HBC employee and 150 Cree from York Factory, set out to negotiate peace. After a journey filled with many hardships, she eventually guided the two groups to an agreement. The treaty between the Dene and the Cree paved the way for HBC’s northern expansion. For this accomplishment, Thanadelthur became known as the Ambassadress of Peace.

HBC wasn’t the only fur trader keen to capitalize on the rich pelts of the New World.

In New France — a French colony centred around the St. Lawrence River in modern-day Quebec — fur traders had, over the course of several decades, established trading relation- ships with the Huron, Cree, and Montagnais peoples, among others. When they learned of HBC’s arrival in Hudson Bay, they were furious, because HBC forts siphoned furs away from New France.

This bitter business rivalry quickly escalated into violence. In the 1680s, New France sent soldiers to Hudson Bay to capture HBC’s forts and to drive the Company from the fur trade.

Over the course of nearly twenty years, the two sides skirmished many times — both on land and on the sea. Sometimes the French would capture HBC’s forts, only to lose them in subsequent counterattacks. The sparring continued on and off for decades, until finally, in 1763, Britain defeated France in the Seven Years War.

The end of the war allowed HBC to focus its efforts on expansion, and for a while profits soared. But soon a new challenge emerged — and, yet again, it came from fur traders in Montreal. In 1779, a group of Montreal businessmen — led largely by Scottish immigrants — decided to challenge HBC’s fur-trading monopoly in the northwest. Founding the North West Company (NWC), the Montrealers planned to beat HBC by heading deep into the interior of North America to trade directly with Indigenous trappers. By doing this, they hoped, the NWC would get the best furs and cut off the supply lines to Hudson Bay.

Soon, the “Nor’Westers” were spreading out across the continent in search of pelts. Along the way, NWC employees such as Simon Fraser, former HBC trader David Thompson, and Alexander Mackenzie mapped vast swaths of North America, becoming the first Europeans to cross the prairies, explore the Rockies, and reach the Pacific Ocean by land.

Unfortunately, history began to repeat itself. The rivalry between the two companies grew increasingly violent — culminating in 1816 with the Battle of Seven Oaks, a deadly clash between NWC and HBC that saw twenty-one HBC traders killed, including Robert Semple, the governor of the Red River Colony in modern-day Manitoba.

Across the Atlantic in England, the government that ruled British North America was growing increasingly impatient. The constant fighting between HBC and the NWC was hurting profits for both companies. In 1821, Britain demanded that the two companies join forces. In return, the new, united company would receive an exclusive trading licence for territories outside of Rupert’s Land. Despite plenty of lingering animosity, the two companies merged under the HBC banner. And from the ashes of past conflicts emerged a reinvigorated company.

Trade Goods

As HBC pushed farther into the continent in search of new sources of furs, the Company’s employees kept careful records of their travels. Over decades, these explorers journeyed thousands of kilometres. It was not easy travelling in the wilderness, and the explorers faced many hardships, from extreme temperatures to injuries and illnesses.

These voyages have typically been described as journeys of discovery, but, of course, the lands these men “discovered” had actually been occupied for millennia by Indigenous peoples. Indeed, Indigenous peoples played a crucial role in guiding and supporting the European explorers, enabling the success of their missions.

The impacts of these explorations were far-ranging; the Europeans’ charts and maps, first-hand accounts, and official reports helped to redraw the maps of North America.

Among the most famous HBC explorers is David Thompson. Thompson was born in London into a poor family but did well in school, leading to an apprenticeship with HBC in the 1770s. He worked for the Company until 1797, when he joined the NWC. During his nearly three-decade career, he mapped almost half of North America. Accompanied by his wife, Charlotte Small, and their family, Thompson travelled more than 88,500 kilometres and surveyed 4.92 million square kilometres of wilderness, establishing trading routes across the Rockies, and along the Columbia River in British Columbia. Thompson’s map-making was so accurate that his work remained the basis of all maps of Western Canada for almost a century.

He also kept detailed journals of the wildlife and the people he encountered. Describing Inuit people, he wrote of the protective eyewear they wore to prevent snow blindness: “Being for eight months of the year exposed to the glare of the snow, their eyes become weak; ... They make neat goggles of wood with a narrow slit, which are placed on the eyes to lessen the light.”

Thompson got along very well with the First Nations people he met. His wife, Charlotte, undoubtedly played a key role in forging both personal and trading relationships with Indigenous peoples. As the Métis daughter of a European father and a Cree mother, she helped to build bridges between the Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities. “My lovely wife is of the blood of these people, speaking their language, and well educated in the English language, which gives me a great advantage,” Thompson said in 1848. Thompson learned to speak at least four Indigenous languages — Blackfoot, Kootenay, Chipewyan, and Mandan — and wrote dictionaries of Indigenous words. The Salish people of the west coast considered him a friend and gave Thompson the name Koo-koo-sint — “The Man Who Looks at Stars.”

Another HBC explorer who relied on Indigenous knowledge to find success was Samuel Hearne. Hearne completed three overland journeys to the “barren lands” west of Hudson Bay between 1769 and 1771. His third journey lasted nineteen months, during which he and his Chipewyan guide, Matonabbee, followed the Coppermine River all the way to the Arctic Ocean.

Matonabbee, the adopted son of an HBC chief factor and his Cree wife, worked for HBC at Prince of Wales Fort, near modern day Churchill, Manitoba, as an “ambassador and mediator” charged with building better relations with Indigenous peoples of the region. Hearne thought very highly of Matonabbee and praised his “personal courage and magnanimity,” adding that “in conversation, he was easy, lively and agreeable, but exceedingly modest.”

Their 5,600-kilometre odyssey to the Arctic Ocean is one of the most incredible overland journeys in North American history. Hearne is also credited with exploring Great Slave Lake and the Mackenzie River system. His legacy includes his memoir, a single portrait, and a poetic piece of graffiti: his own name, beautifully engraved on a large stone at the mouth of the Churchill River.

Another HBC explorer, John Rae, is today famous for solving a mystery that captivated the minds of Europeans for centuries — the location of the fabled Northwest Passage.

Beginning in 1846, Rae, a Scotsman, made four separate journeys into the Arctic in search of the passage. Unlike some European explorers, Rae admired and respected the Indigenous peoples he met. He learned their traditions and adopted their techniques of hunting and dress and their modes of travel.

In 1854, during his final voyage to the Arctic, Rae discovered the last few links in the Northwest Passage, thereby proving its existence. He also solved the mystery of what had happened to Sir John Franklin, a famous British sea explorer who disappeared while searching the Canadian Arctic in 1845 for a Northwest Passage to China.

On March 31, 1854, Rae met a group of Inuit who possessed a gold cap band from a European-style hat. An Inuk man told Rae he had found it nearly a twelve-days’ journey away, at a site where more than thirty “white men” had starved to death. This story was confirmed two months later, when Rae met another group of Inuit that showed him a silver plate with the words “Sir John Franklin, K.C.H.” engraved on the back.

By the 1850s, HBC had spread throughout the northwest, with forts and trading posts dotting the landscape from what is now Yukon Territory to the former Oregon Country (in the modern-day northwestern United States).

But with the dawn of the 1860s the Company felt increasing pressure to give up its control of Rupert’s Land. The pressure came from both the United States and the newly formed Dominion of Canada, which was created in 1867 with the union of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and the Province of Canada (Ontario and Quebec). It was no secret that the Americans wanted to take over the entire northwest part of North America; Canadian politicians realized that if they didn’t annex Rupert’s Land the Americans would.

HBC’s British investors decided to negotiate a deal with Canada to transfer Rupert’s Land in exchange for money and new land elsewhere in the West. In November 1869, HBC signed a Deed of Surrender that would forever transform the Company — and the country.

The Rupert’s Land transfer caused much upheaval for the people who lived in the region, and particularly for the Métis of the Red River Colony.

Large Métis populations lived around trading posts in Rupert’s Land, including in the Red River region of modern-day Manitoba. When news of the Rupert’s Land transfer reached the Red River Colony, it angered both the Métis and the non-Métis inhabitants. They had not been consulted about the deal, and they feared that the Canadian government would break up their farms and take their land.

The Red River Resistance of 1869–70, led by Métis leader Louis Riel, ultimately resulted in the creation of the province of Manitoba.

For HBC, the Rupert’s Land purchase marked the beginning of a new era. Under the terms of the deal, the government of Canada gave HBC £300,000 as well as one twentieth of all the land in the fertile belt stretching from Lake of the Woods in modern-day northwestern Ontario to the Rocky Mountains in Alberta. The Company also received an additional twenty thousand hectares of land surrounding its trading posts. The timing was perfect, because the fur trade as a business was starting to decline. Beaver hats were falling out of fashion, and fewer and fewer furs were being sold.

As thousands of new settlers flooded into Western Canada, HBC realized it had an opportunity not only to sell land to the newcomers but also to supply them with items they needed to establish their new homesteads. After nearly two centuries, the fur-trading era was ending, and the retail era was about to begin.

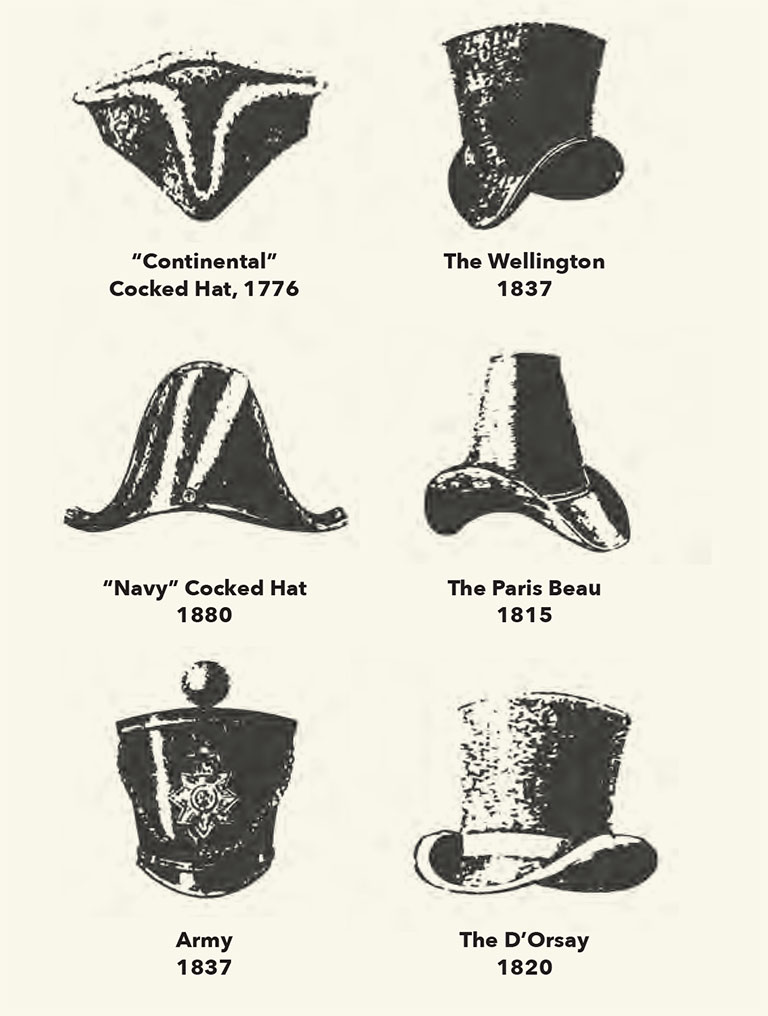

BEAVER HATS

From the late-sixteenth to mid-nineteenth centuries, beaver hats were an essential aspect of men’s fashion across much of Europe.

Not only were they extremely valuable, often treated as a family heirloom passed on from father to son, but a hat’s design also denoted an individual’s social status and occupation.

Hats were made of a variety of felt, but the best-quality and most-popular felt was made from beaver furs. The vogue for beaver felt declined in the mid-nineteenth century, when silk was found to be less expensive yet just as stylish.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Beautiful woven all-silk bow tie — burgundy with small silver beaver images throughout. This bow tie was inspired by Pierre Berton, inaugural winner of the Governor General's History Award for Popular Media: The Pierre Berton Award, presented by Canada's History Society. Self-tie with adjustments for neck size. Please note: these are not pre-tied.

Made exclusively for Canada's History.