Driving Change

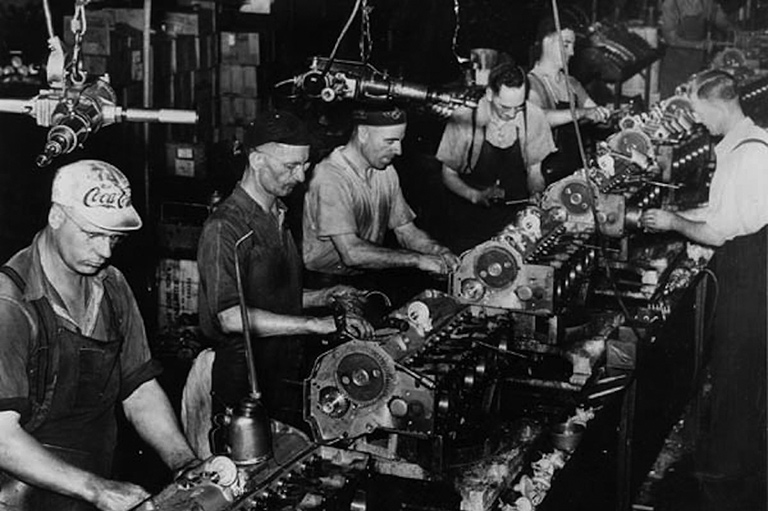

As the guns of war fell silent throughout the spring and summer of 1945, Canada’s workers looked into the face of upheaval. The wartime economy had been running full tilt, with women filling the gaps left when men took up arms. Now that the fighting was over, husbands, fathers and sons were coming home, and despite government plans to retrain veterans, many expected to pick up where they’d left off. With the diminished need for armaments and supplies, unemployment in wartime boom industries was inevitable, although increased demand for new consumer goods created additional employment.

Under the War Measures Act, home-front workers had forgone many of the rights they had achieved before the war: Unions weren’t allowed to negotiate wage increases since wages were frozen, work stoppages were severely curtailed and union membership drives were limited. Despite that, there were still hundreds of strikes during the war and union numbers doubled between 1939 and 1944, largely because labour shortages had led to new-found worker confidence in job security.

After the fighting had ceased, workers expected to be rewarded for their sacrifice, while unions wished to solidify their growing status. Some politicians, including Windsor Liberal MP Paul Martin Sr., believed it was time for a society in which workers shared in the making of decisions in partnership with government and corporations. Martin’s fellow cabinet minister C.D. Howe, on the other hand, pressed for business gains and was known to have sometimes labelled Martin a Communist.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

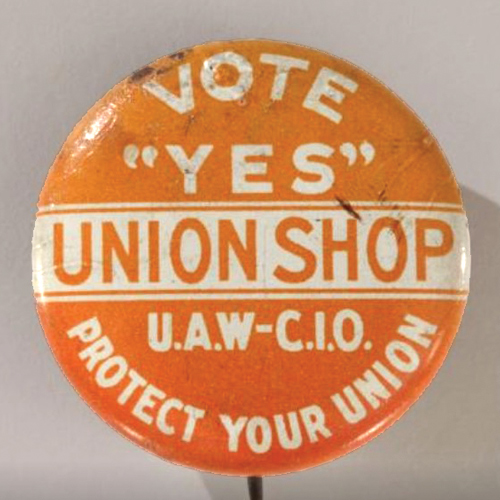

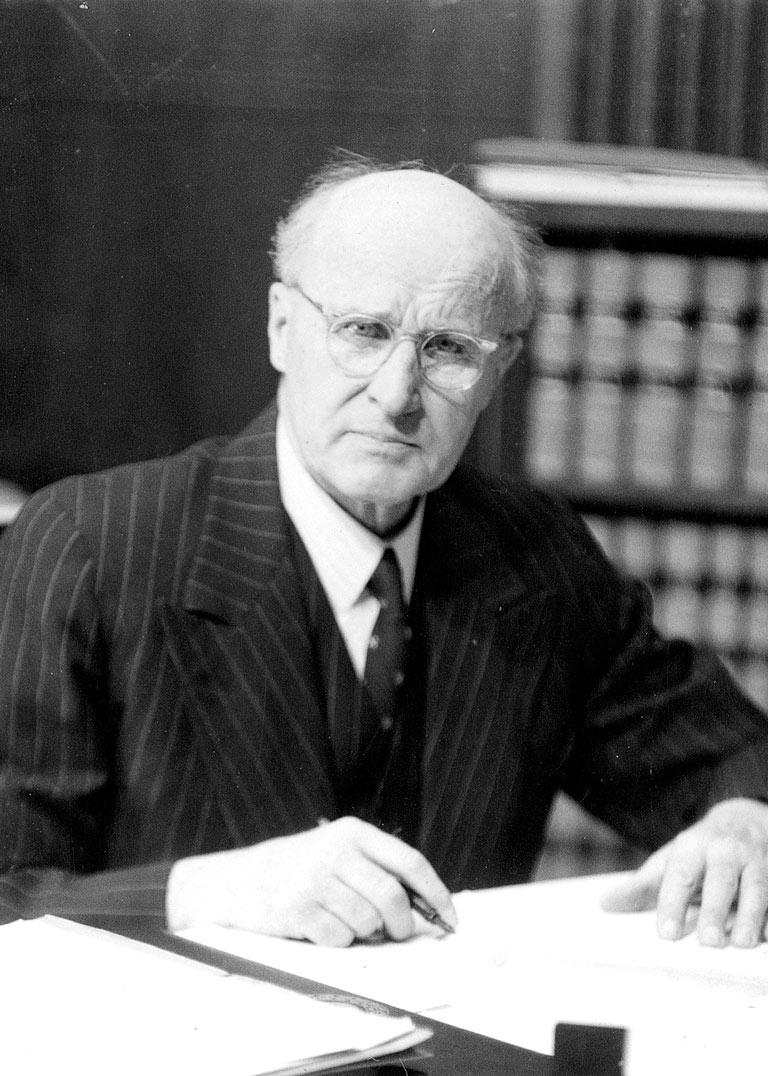

The clash of ideas over unions’ power came to a head 80 years ago during a job action at the Ford Motor Company of Canada in Windsor, Ont. It led to the adoption of the Rand Formula, named for Supreme Court Judge Ivan C. Rand and now recognized as a pillar of labour relations. The Rand Formula set the stage for postwar worker gains that have expanded the middle class and fuelled prosperity.

How did it come about?

On Aug. 31, 1945, Ford of Canada announced that, with lower postwar production needs, it was laying off 800 workers at its Windsor facility. Rumours spread of more to come, and in fact, that number was soon increased by about 1,650. Canada’s autoworkers were represented by George Burt, a former plumber and General Motors line worker at its Oshawa, Ont., plant, who served as Canadian director of the Detroit-based United Auto Workers (UAW) union. Burt knew he had to act, but he also knew that he needed to answer to his boss, Roland Jay Thomas, the UAW president in Detroit.

Thomas and his soon-to-be replacement, Walter Reuther, reflected the growing anti-Soviet and anti-Communist sentiment in the United States. They looked on at the growing labour militancy in Windsor and initially refused to authorize Burt’s call for a strike. Burt later said he believed he was being urged to tread softly because the Americans feared turning public opinion against a union seen by many as too radical.

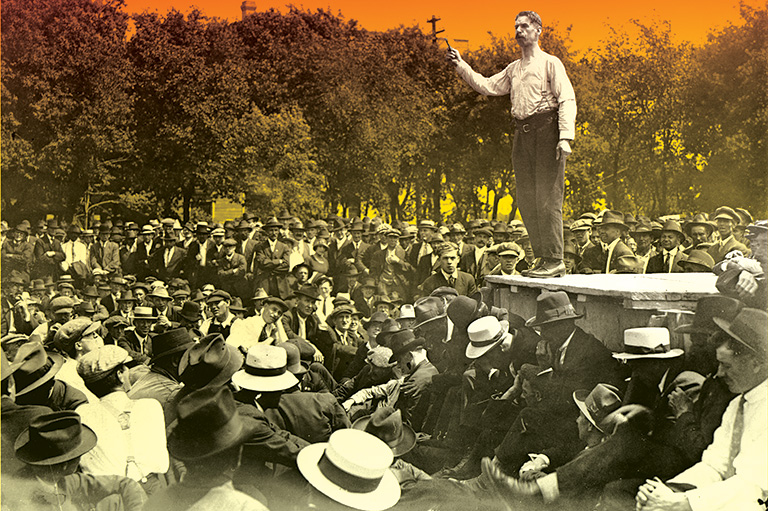

During the 1930s and ’40s, industrial organizations such as the United Auto Workers of America, the Steel Workers Organizing Committee and the Mine Workers Union of Canada often found their demands branded as “radical.” Those demands included calls for shorter hours, safer conditions and protection from dismissal for union-related activities. Labour didn’t plan to take its foot off the gas pedal and it was clear that labour relations would be in for a hard landing.

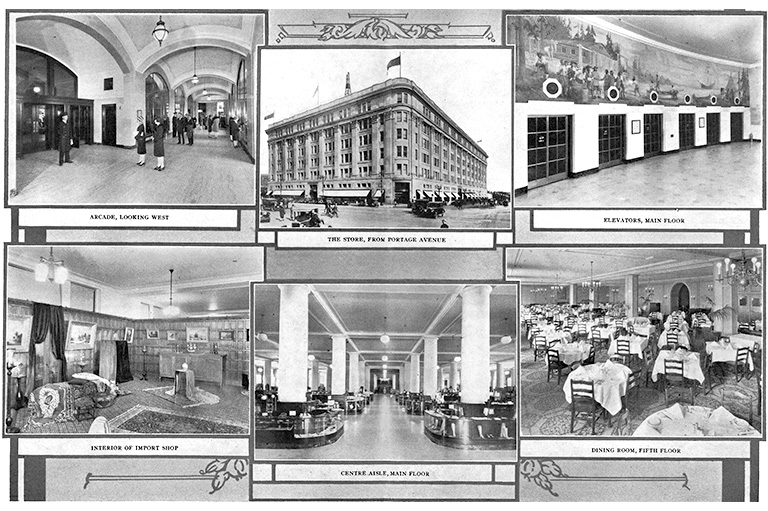

That landing hit no harder any place than in Windsor, a city that had been known since the First World War as the nation’s automotive capital — Canada’s “motoropolis.”

The year 1945 was an inflection point for Canadian labour. With the war over, labour was turning its attention not just to worker wages but also to the issue of union security — the right to exist and prosper. Unions wanted automatic dues checkoff, which would require employers to collect worker dues and hand the money to the duly chosen unions. That would provide the unions financial stability and let them devote their time to matters beyond regular union housekeeping.

Chief among their priorities was the pursuit of “social justice.” Taking their cue from those such as the American moderate Reuther, union leaders believed they had a role to play in improving society through broad social change, which included advocating for pensions and health-care benefits. No union was more vocal in its desire to demonstrate its social responsibility than the UAW.

But how quickly should they move? How far should they push? With Thomas’s initial refusal to support a strike at Ford Canada, Burt faced a dilemma. Torn between his own conscience and the head of his union, Burt consulted and weighed his options.

Burt knew he enjoyed the ear of left-leaning Liberal politicians, such as Martin and David Croll, a former Windsor mayor who was by then a Toronto MP, both of whom had courted labour’s support. Both had a pipeline to Liberal Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, a fact that added to Burt’s confidence in the decision he was about to make — one destined to resonate through Canadian labour to present day.

Burt pressed for a strike mandate and the workers responded with a big one. Seeing that strong worker support, American union leaders acquiesced to Burt’s views. Ford of Canada workers walked off the job on Sept. 12. Wages weren’t the issue — union security was. And the union believed that the matter of security could be resolved, in its favour.

The company rejected that route, with Ford of Canada president Wallace Campbell later telling the Canadian union leader he felt like a “guinea pig.” Burt said Campbell told him that if he — Campbell — showed weakness, he would be reviled by other industrial employers in Canada. If the government wanted automatic dues checkoff, Campbell said, it should legislate.

There was no doubt in George Burt’s mind how important this strike would be, not only to the Ford workers but also to Canadian labour, in general. “The outcome of the Ford situation, and the situation generally prevailing in Windsor, will affect not only the future of the UAW, but also it will set a pattern for postwar labour relations in the Dominion of Canada,” Burt told a conference of Canadian UAW leaders in June 1945.

Burt’s leadership marked a key moment in Canadian union independence. By acting without the initial support of his American boss, Burt was setting the stage for Bob White to lead Canadian automotive workers out of the UAW four decades later and create the Canadian Auto Workers union. (The fallout from the decision is still being felt, with the UAW thumbing its nose at Canadian workers earlier this year when it endorsed President Donald Trump’s automotive tariff plan.)

Burt might have understood the strike’s importance, but he couldn’t have known the job action the union was initiating would push federal politicians to the edge of calling out the troops, or that Ontario Premier George Drew would be moved to declare in a telephone conversation on Nov. 5 with acting prime minister J.L. Ilsley, “There is anarchy in Windsor.”

The strike dragged on for weeks. Many in the community rallied to the workers’ side. Farmers donated food, businesses made donations and a soup kitchen, staffed by the women’s auxiliary of Ford workers, was established.

Advertisement

In November, however, as winter’s chill began to set in, frustrations rose. Ford feared the shuttering of its on-site power plant by strikers would lead to cold-weather damage.

On Nov. 2, Ontario commanded that Windsor police escort maintenance workers into the power plant. Pickets held steady and police, outnumbered by strikers, withdrew. While confrontation had been averted for the moment, Ontario Attorney General Leslie Blackwell then dispatched 125 provincial policemen, with the Mounties sending an equal number to stand by in Windsor.

Support for the Ford strike at other Windsor workplaces appeared to surge on Nov. 5, when 20,000 workers, representing three-quarters of the city’s industrial workforce, failed to show up to work.

Burt, drawing inspiration from a similar action that had once taken place in Michigan, called for a vehicular blockade to bar police from entering the Ford complex. It proved to be one of the most dramatic moments in Canada’s labour history.

The blockade began slowly — initially with just employees’ vehicles — but soon, others joined. City buses entered the jam, and strikers began commandeering the vehicles of passersby. In its Nov. 5 final edition, the Windsor Daily Star reported: “Violence broke loose in Windsor this morning, when private citizens were the victims of strikers at the Ford Motor Company of Canada, Limited.… If any driver protested the seizure of his car, he was threatened with violence.”

The blockade made headlines across Canada and the United States. According to the Windsor Daily Star, city police reported 150 vehicles stolen by strikers. An insurance company representative told the newspaper that car owners wouldn’t be indemnified against damage. It was estimated that as many as 2,000 vehicles were involved in the blockade. A Detroit newspaper said the strikers demonstrated a “carnival spirit,” with a band and bagpiper, while union members and their families sang and danced in the streets.

At Queen’s Park in Toronto, Premier Drew kept in close telephone and telegraph contact with acting prime minister J.L. Ilsley, while Mackenzie King attended a Commonwealth conference in London. Drew said he feared a force of 2,000 “Communist” strikers was coming from Detroit.

If workers continued to be a threat to Ford’s property, Drew told Ilsley, “a highly trained force” of Canadian military should be sent. Ilsley said that while he wouldn’t support using the military at the moment, it remained an option. The Ontario and federal justice ministers also conferred on potential military intervention. Then, as onlookers’ vehicles were seized and 14 city blocks were shut down, Drew expressed his concern to Ilsley about the “anarchy.”

Drew saw two issues at play: the strike, and maintaining law and order. He would not advocate police or the military to settle a strike, only to maintain the law.

George Burt shuddered at what might come next. Bloodshed must be averted. Late in the day on Nov. 7, Burt appealed to workers to end the blockade. Make no mistake, he told them, if order was not restored, “the Canadian Army will be called in.” The workers heeded his warning, and the process of untangling the blockade began.

How close did the federal government come to calling in the troops? Transcripts suggest at one point that Ottawa was prepared to make it happen, and as Burt pleaded with his members to call it off, rumours spread that the military was prepared to move.

The strike continued after the blockade, but as Christmas approached, 99 days after it began, Ford of Canada agreed to binding arbitration and the workers agreed to return to their jobs. Federal Justice Minister Louis St. Laurent, urged on by Windsor’s Paul Martin, appointed Supreme Court Justice Ivan C. Rand as arbitrator. Rand concluded that full union dues checkoff was warranted. While Ford would not be deemed a “closed shop,” his decision had the same effect.

In short order, the Rand Formula began to be applied to many other union settlements, although it was far from universal.

At a conference of the Canadian UAW division in January 1946, Burt remarked: “…we have confidence that the weight of this strike has had the effect of shaking the government into a greater realization of the problems of organized labour and has awakened the Canadian people to the realization that the success of post-war rehabilitation depends a great deal upon the labour movement.”

With the Rand Formula spreading to other unions and the resulting guarantee of a steady flow of workers’ dues, those unions no longer needed to concern themselves with membership sign-ups and dues collection; they could turn their attention to worker benefits and broader social priorities, including health and safety, workplace diversity, pay equity and job security. Driven by union leaders such as George Burt and Walter Reuther, the era of social unionism had dawned. Gains made by union workers rippled through the economy to other worker groups and contributed to an expanding of the middle class and national prosperity.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

In the coming decades, the strike at Ford of Canada would take its place in the pages of worker history alongside the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike and the 1949 Asbestos Strike in Quebec. The Ford action has been labelled “Canada’s most underrated rebellion” by Vancouver-based labour economist Jim Stanford. It’s further endorsement of labour historian David Moulton’s contention that the historical view of Canada as “the peaceable kingdom” is a myth, one that disregards the bitter struggles workers endured to achieve the employment rights they enjoy today.

“Rand gave unions security to become permanent actors,” says Charles Smith, a labour expert at St. Thomas More College at the University of Saskatchewan. “It’s hard to imagine some of the big collective bargaining gains without Rand.”

But are those rights sacrosanct? Could modern-day governments strip away protections that workers fought to gain?

National labour leaders, including Canadian Labour Congress president Bea Bruske, have warned that workers aren’t safe from politicians who favour business over employees. “For years, we have faced governments weakening labour laws, making it harder to organize, and we’ve seen that it means a widening wealth gap in this country,” Bruske said last year.

As for the Rand Formula itself, Charles Smith says: “If a government felt threatened by the labour movement, I could definitely see a push for American-style right-to-work laws, for example. And that would destroy the legacy of Rand.”

Social Justice

Edwin Charles Garvey was a Basilian priest who began teaching at Windsor’s Assumption College in 1937. (It was renamed Assumption University of Windsor in 1956.) A strong labour union advocate who often spoke against radicals and Communists, Garvey defined social justice as “common action for the common good.” Following the lead of American trade union leader Walter Reuther, Canadian labour leaders believed that their role went beyond collective bargaining and settling grievances, and that it was their destiny to bring about broad social change to improve the condition of all people, not just union members.

Women in the Workplace

The Second World War was a watershed for workers’ rights in Canada. During that time, the National War Labour Board sided with unions in their fight for equal pay for women, although many employers resisted. When Ford of Canada was told that it had to pay women the same as male workers on the factory floor, the company refused to hire women for those jobs for many years.

The unions fought back. At Gotfredson Truck in Windsor, Ont., management argued that women didn’t perform equal work. The United Auto Workers took the matter to arbitration. Two loading-dock workers, a man and a woman, were called to testify. “Can you do the work of this man?” the woman was asked. She responded by picking the man up, turning and setting him down.

The arbitrator ruled that Gotfredson would have to pay men and women equally.

The war helped transform Canada’s workforce. Between the beginning and end of fighting, the number of female workers in Canada aged 14 and older nearly doubled, from 570,000 to about one million. A survey done for the government publication Canadian Affairs in 1945 found that only half of women expected to go back to “housekeeping chores” and only five per cent looked forward to it. Over the next quarter century, women’s participation in the workforce increased from 25 to 39 per cent. Today, that number is about 61 per cent for those aged 15 and above.

The Rand Formula

Named for Canadian Supreme Court Justice Ivan C. Rand, it requires employers to deduct union dues from all workers who are covered by a union contract. While it doesn’t force a “closed shop” — workers are still not required to belong to a union — it eliminates the workers’ right to withhold their dues while benefiting from the union’s work. In rare cases of personal belief, workers may direct their dues to a non-union recipient, such as a charity.

As a core pillar of the Canadian union movement, the Rand Formula imposes requirements on both labour and management. Strikes may legally occur only after an agreement expires. According to labour historian Jeremy Milloy, the Rand Formula “recognized and safeguarded nonradical unions. It created a framework for orderly, regulated union organizing and negotiations.”

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement