The Lonesome Death of an Alien Cloakmaker

On Friday afternoon, July 14, 1899, Alexander Reder loaded his pockets with stones and jumped into Lake Ontario. Alex Johnson, an elevator operator employed at Gooderham᾿s grain elevator; saw Reder leap and hastened to pull him out with a pike pole. Reder was still alive after he was brought to the surface but died about fifteen minutes later despite resuscitation efforts.

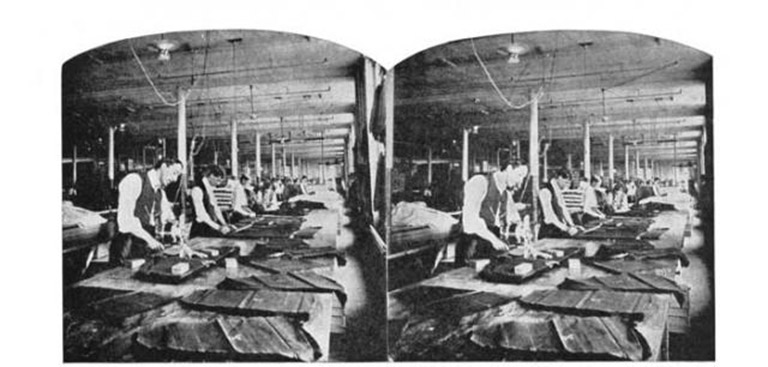

A cloakmaker by trade, Reder had just arrived in Toronto after signing a contract in New York City on July 10 with the T. Eaton Company. Sigmund Lubelski, a foreman in the cloakmaking department, had been dispatched to the U.S. to recruit new workers because earlier that month Eaton᾿s employees had gone on strike. According to the contract, Reder was to work as an operator for at least six months. Failure to do so would result in the cost of transportation from New York to Toronto being deducted from his wages.

At the July 17 coroner᾿s inquest, Jacob Machinist, one of the twenty-seven workers signed by Lubelski, testified that he and the other workers had been given assurances no strike was in progress between Eaton᾿s and its employees, which was contrary to an advertisement in a Hebrew-language newspaper published in New York warning of the very strike. When the men reached Toronto they learned the truth and refused to work. A number of the men, including Reder, confronted Lubelski, demanding that he pay their return fare. Lubelski refused. Another New York cloakmaker, Joseph Newman, testified that on Friday morning he had spoken with a despondent Reder, who said he would rather starve than work as a “scab.”

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Sigmund Lubelski also testified at the inquest. He openly admitted to signing Reder to a contract in New York City. Indeed, he produced the contract.

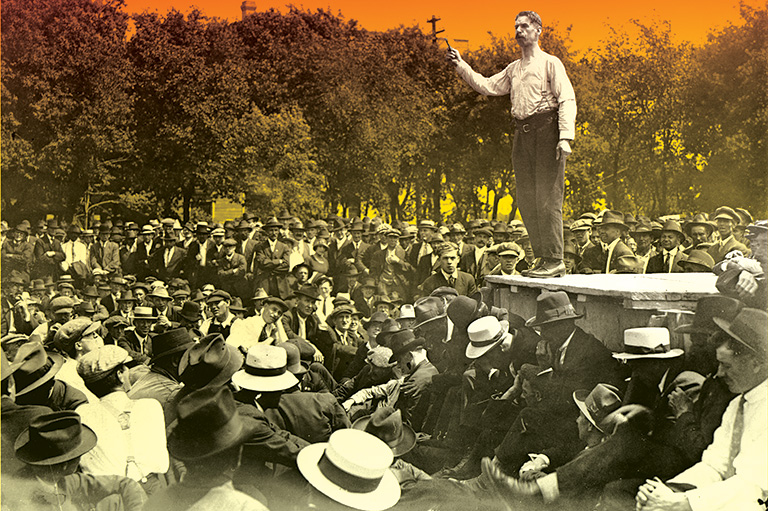

The inquest was attended by a large delegation of cloak-makers, and six police were dispatched to maintain order. The jury᾿s verdict pleased the crowd:

That Alexander Reder, who died on the 14th day of July, deliberately committed suicide by jumping into the bay. The cause of the act was despondency, the result of being brought to Toronto under false pretences by Sigmund Lubelski, acting for the T. Eaton Company.

The use of replacement workers during strikes was both commonplace and legal. There was, however, one exception. The Alien Labour Act of 1896 prohibited the importation of workers from some countries, including the United States, into Canada under contract, unless they fell within an exempted category, such as entertainers. Alexander Reder and the twenty-six other cloakmakers were not exempted under the law. Hence, Sigmund Lubelski's sworn testimony before the coroners jury, and his production of Reders contract of employment, amounted to a confession of illegally importing foreign workers.

Daniel J. O'Donoghue, a one-time member of the Ontario Legislative Assembly and a prominent trade unionist with strong ties to the Liberal party, wrote to Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier two days after the inquest appealing for action to be taken “against the criminals — murderers, morally at any rate — in this case.” His request fell on deaf ears. Sigmund Lubelski and the T. Eaton Company went unpunished for their violation of the law.

Advertisement

Reder᾿s suicide and its aftermath provides a window onto the processes through which organized labour and employers tried to mobilize state resources to shift the balance of power between them. Employers in the late nineteenth century strongly supported freedom-of-contract ideas when it came to their relations with workers. In their view, the role of the state was to define and protect property and contract rights. Employers should have the right to contract with anyone who was willing to work for the wages the employer was prepared to pay. Employees who found the terms on offer unacceptable were free to leave, but should not be allowed to interfere with other workers who were prepared to take their places.

For this kind of freedom of contract to work in the employers᾿ favour, however, there had to be a labour surplus. During much of the nineteenth century, labour shortages, not surpluses, prevailed, and so employers favoured policies that permitted the recruitment of foreign workers, largely from the British Isles.

By and large, the interests of employers were supported in labour law and state immigration policy. The law recognized that workers were permitted to join trade unions and strike, but it prohibited them from engaging in a wide range of activities that might interfere with the rights of employers and other workers who were not members of the union to contract freely with each other. In regard to immigration, there was nothing to stop employers from actively recruiting workers from outside the country. Indeed, government immigration agents assisted their efforts.

Unionized workers never accepted the legitimacy of strikebreakers. Then as now, strikebreaking was the leading cause of picket-line violence, and provided the most frequent occasion to call police and lay criminal charges against striking workers. As well, unionized workers campaigned unsuccessfully to restrict the recruitment activities of immigration agents, complaining that excess competition was driving wages below the level necessary to support a respectable standard of living for a working-man᾿s family.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

How, then, did the Alien Labour Act come to be enacted? Its roots go back to the 1880s, a decade in which organized labour in Ontario was beginning to develop a presence and an ability to influence politicians. For instance, organized labour successfully lobbied the Liberal government of Oliver Mowat to enact the 1886 Factories᾿ Act, one of the first statutes to provide minimum standards in employment. That same year, John Morison Gibson, a Liberal member from Hamilton, introduced Bill 46, which aimed to void contracts of employment entered into outside the province. This was required, Gibson explained, because Ontario workers needed “a sort of protection” against the practice of employers “to arrange with labour across the line to come in and neutralise the effects of the strike.”

Neither Mowat nor the opposition leader, William Meredith, disagreed with the intent of Gibson᾿s bill and it was referred to a select committee.

Inspired by the Foreign Contract Labor Act passed by the United States the previous year, the legislators modified Gibson᾿s bill by allowing workers — but not their employers — to enforce such foreign contracts, and by exempting certain workers — primarily cultural and professional workers and those whose skills were in short supply. The amended bill passed.

Despite the apparent legislative consensus that importation of labour under contract was undesirable, especially when used to break strikes, the law did little to stop the practice. It merely prevented the employer from enforcing contracts made in violation of the Act, but it did not prohibit the importation of foreign labour. An employer who imported contract labour faced no penalties or sanctions.

In time, the federal government enacted its own law. This was in response to the Americans more stringently enforcing their Foreign Contract Labor Act in the late 1880s. Canadian workers soon felt its pinch. For example, in 1889 between 250 and 300 residents of the border town of Gananoque complained employment had been denied them in the United States. The following year, their Tory member of Parliament, George Taylor, introduced a private member's bill copying the American act. Labour organizations and a few other members supported the bill, but both the Conservative government and the Liberal opposition rejected in principle such restrictions on labour mobility. Nevertheless, they were concerned about American actions against Canadian workers and used the opportunity to signal their displeasure. The bill was given second reading and referred to a select committee, which recommended that the matter be put over to the next session, to be acted upon only if no satisfactory arrangement was made with the United States.

In fact, the government was unable to negotiate a satisfactory resolution of its dispute with the United States over the application of the law to Canadian workers. Despite this, it still refused to support Taylor᾿s bill, reintroduced year after year. The minister of justice, John Thompson, justified his government᾿s stand on the ground that retaliatory action would be ineffective and that Taylor᾿s bill would impede the overriding goal of promoting immigration of working people into Canada.

The turning point came after the defeat of the Conservatives at the polls in 1896. Although the new prime minister, Wilfrid Laurier, had not been a supporter of retaliatory legislation in opposition, grievances were mounting over the application of the American law to Canadian citizens. Members from both parties were under pressure from their constituents to have some government action. Reluctantly, Laurier agreed that a symbolic response to American protectionism was necessary. Thus, the Alien Labour Act was passed in April 1897.

The act prohibited the importation of foreign labour into Canada under contract. All employment contracts made outside Canada were void, and persons who were convicted of violating the law were liable to a fine of $1,000. Further, immigrants unlawfully brought into the country could be removed at the expense of the person who had unlawfully brought them in under contract. So as not to harm legitimate recruitment activities, the act exempted various classes of workers, including skilled workers not available in Canada, from its application.

Advertisement

In fact, a number of customs officers were appointed by the government as enforcement agents, but by the beginning of the next session numerous complaints were voiced about the act᾿s ineffectiveness. This became abundantly apparent in May 1898 during two strikes in Toronto, one by boot and shoe workers at the J.D, King factory and the other by upholstery workers employed by the Gold Medal Furniture Company owned by W.J. McMurtry, an active member of the Canadian Manufacturers᾿ Association.

Both employers were alleged to have imported strikebreakers from the United States under contract. This led to picket-line confrontations and the arrest of eight striking workers at the J.D. King factory. E.A. Du Vernet, a rising star of the Toronto bar, was retained to represent these worker and to seek enforcement of the Alien Labour Act. Affidavits were secured from some defecting strikebreakers and sent to the minister of justice and, presumably, to two local Conservative members of Parliament, Edward Frederick Clarke and. Clarke Wallace, who raised the matter in the House. The government explained that the problem of nonenforcement stemmed from the fact that no agent had yet been appointed to administer the law for the Toronto area.

In response, the government appointed lawyer and former Toronto mayor William Barclay McMurrich to investigate. After several weeks, he declared that the evidence did not warrant application of the alien labour law. The strikes were subsequently settled, but only after another twenty-one workers had been arrested and charged for picket-line activities.

Later in June the strike at Gold Medal resumed when the American replacement workers were given preference over returning strikers. The union gathered additional evidence that Gold Medal and its manager, W.J. McMurtry, were violating the Alien Labour Act. This time the government commenced a prosecution against McMurtry and a November 1898 trial date was set. Before the matter proceeded, however, McMurrich was instructed by the Dominion government to desist.

There are two possible reasons for this turn of events. First, on August 25, McMurtry wrote to Laurier. He insisted the statutory declarations had been obtained when the American upholsterers were drunk. Moreover, he complained, the union had instigated the strike by demanding excessive wages. “We feel satisfied that the Government has no intention of aiding .... a notorious agitator [who is of]…. a certain class of men who expect to share in the proceeds of any firm and whose socialistic qualities give them delight in doing all the damage they can.”

But Laurier had larger concerns on his mind. He was scheduled to attend a November meeting in Washington, D.C., of the Anglo-American Joint High Commission, which had opened its sittings in Quebec City in August in an effort to resolve some long-standing disputes between Canada and the United States, including alien labour legislation.

Presumably Laurier did not want to risk souring the atmosphere by having the first prosecution under the Alien Labour Act conducted in the midst of these discussions. Indeed, E.L. Newcombe, the deputy minister of justice, wrote on November 8 that “at present the Attorney-General is not prepared to authorize any prosecutions under the Act.”

Canadian forbearance failed to produce a diplomatic solution with the Americans, nor, as the response to Reder᾿s July suicide and inquest suggests, did the Canadian government adopt a more vigorous enforcement policy.

The passivity of the government is even more remarkable given the correspondence with Eaton᾿s that preceded the department store᾿s actions. Anticipating a strike, Eaton᾿s wrote to McMurrich at the beginning of June 1899 seeking permission to import cloakmakers under contract on the ground that there was a shortage in Toronto. Not receiving a prompt response, Eaton᾿s pressed the matter further arguing that, unless they received permission to hire, they would be forced to import merchandise rather than produce it locally. McMurrich passed the information to the minister of justice who instructed him to advise Eaton᾿s that no prosecution would be authorized if the facts were as Eaton᾿s asserted.

The failure of Eaton᾿s to inform the government that its dispute with the cloakmakers᾿ union lay at the heart of its labour shortage should have been seen for what it was: a clear misrepresentation of the facts. This was apparent to McMurrich, even before Reder᾿s suicide. Imported workers had presented him with three statutory declarations alleging that they had been brought to Toronto under contract and under false pretences. McMurrich conveyed the information to the minister of labour and sought instructions. On July 17, the day of the inquest into Reder᾿s death, McMurrich received his reply: the matter was under consideration. And that is where it stayed.

The experience of Toronto workers with the Alien Labour Act was repeated elsewhere. There is no evidence that the federal government ever intended to aid striking workers, and even if the act had the potential to do so, the record shows the government was quite willing to see it nullified. A law on the books meant little without the political will to implement it. When it came to legislation favouring the interests of workers, this will was chronically lacking. In the fall of 1899 the Ontario executive of the Trades and Labour Congress noted in its report, “It has been the experience of every labour man that after the fight to get an Act passed has been made and it has been made law the trouble has only commenced, for you have got to keep hammering away all the time to make the Government put the law into force, and if the people who are opposed to the Act have any pull with the Party in power it is almost impossible to get any Act in the interest of labour enforced.”

The lonesome death of Alexander Reder, the alien cloakmaker, fully justified this pessimistic conclusion.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement