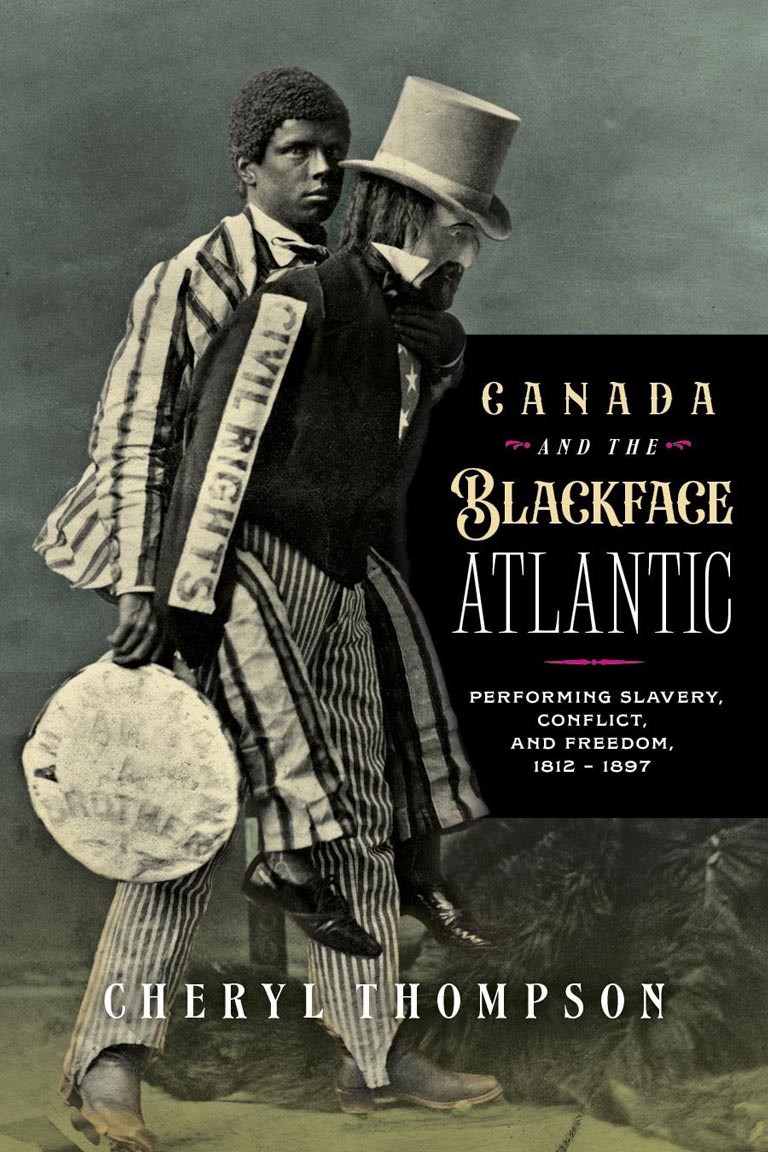

Canada and the Blackface Atlantic

Canada and the Blackface Atlantic: Performing Slavery, Conflict, and Freedom, 1812-1897

by Cheryl Thompson

Wilfrid Laurier University Press

302 pages, $49.99

What if Canada’s national anthem were shaped by blackface? In Canada and the Blackface Atlantic, Cheryl Thompson uncovers a story most Canadians have forgotten (or never knew): Calixa Lavallée, composer of “O Canada,” once toured in the United States as a blackface minstrel with the Union Army as it fought in the Civil War. Thompson’s book makes clear that blackface was never just an American pastime; in the 19th century, it was a staple of Canadian popular culture. In a country that celebrated the Underground Railroad, Canadians romanticized the plantation South.

Drawing on a remarkable archive, including more than 1,100 newspaper articles and 168 images, Thompson documents blackface in Canada across theatres, schools and even churches. She builds on sociologist Paul Gilroy’s concept of “the Black Atlantic” (tracing the movements of Blackness across geographies of space and place) — and scholar Robert Nowatzki’s term “the Blackface Atlantic” — to demonstrate that caricatures themselves circulated as commodities, traded, sold and exchanged for white amusement. From its inception, blackface was entangled with the lasting impact of slavery, Thompson argues. It borrowed from the British stage, Irish tradition, the songs and movements of Africans (enslaved and free) and culture that was born across the scattered landscapes of transatlantic slavery.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Blackface emerged in the American South through figures such as Thomas Dartmouth Rice (often remembered as the father of minstrelsy) and his act “Jump Jim Crow.” It soon migrated north, taking root in Canada through such productions as Uncle Tom’s Cabin and popular performers like Colin “Cool” Burgess and the aforementioned Lavall.e. By the mid-1800s, the southern plantation was reframed, if unintentionally, as nostalgic, helping blackface minstrelsy evolve into its racially charged progeny. It also reasserted colonial hierarchies and stripped its Black subjects — especially within the Canadian context — of nationhood, citizenship and agency, as caricatures of African Americans shaped how Blackness was defined.

This isn’t simply a story of subjugation, though, as Thompson centres Black autonomy within her book. She highlights Toronto’s Black community, which unsuccessfully petitioned the city to revoke licences from circuses and menageries staging “certain acts, and songs” that depicted “Negro Characters” as early as the 1840s. Concert singers like Elizabeth Greenfield forced white audiences to reckon with their biased perceptions of Blackness by blending the African American experience with European-trained operatic mastery. Thompson, an associate professor at Toronto Metropolitan University’s School of Performance, also traces a Black theatrical circuit that gave Black men a performative measure of agency, which nonetheless provided some financial stability.

“To learn about blackface,” writes Thompson, “is to (re)learn the story of the Atlantic world and Canada’s place within it.” That is the book’s achievement; it reframes Canadian history through a practice most would prefer to ignore. By showing how caricature and culture were deeply bound to slavery, race and resistance, Thompson leads readers to conclude that blackface did not merely happen in Canada, it helped create both the “elusive structure of racism that [binds us all]” and, more disturbingly, our nation itself.

Thanks to Section 25 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Canada became the first country in the world to recognize multiculturalism in its Constitution. With your help, we can continue to share voices from the past that were previously silenced or ignored.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement