Lore and Legends

Lake Leviathans

Drive northwest from Winnipeg on Provincial Trunk Highway 6, and you’ll enter a channel of land running between huge bodies of water: Lake Winnipeg to your right and lakes Manitoba and Winnipegosis to your left. Get used to it, because the next four hours (assuming you drive the speed limit) are going to be spent between them. These lakes are important culturally, economically, and — possibly — cryptozoologically. That’s because Lake Manitoba and Lake Winnipegosis might hold more than just prize sturgeon.

The stories of Indigenous people and settlers alike describe sightings of a strange creature: a long, snaky figure, often with a horse-like or diamond-shaped head, making its way through the waves. In the 1960s, land inspector Tom Locke coined the terms Manipogo and Winnipogo, depending on whether the beast was spotted in Lake Manitoba or Lake Winnipegosis.

What makes the stories convincing is the remarkably normal behaviour of this reported sea snake. Aside from its long, serpentine shape and the shrieking sound it makes on surfacing, it does not glow, fly, or recite dire prophecies. In fact, it acts pretty much like any other marine animal — leading believers to suggest that Manipogo and Winnipogo are members of an as-yet-undiscovered species. Skeptics counter that these stories reflect mistaken sightings of moose (to explain the horse-like head) or large sturgeon (which can grow up to 2.5 metres long). Just in case, don’t stop to fish — stick to Winnipeg’s famous pecan-and-caramel schmoo torte instead.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Chenu: The Ice-Hearted Monster

A long time ago, according to a traditional story recounted by Mi’kmaw poet Julie Pellissier-Lush, a kind, beautiful Mi’kmaw woman refused to marry an evil man. Stewing in anger, the man created a powerful medicine that would transform the woman into a monster with a heart made of ice.

When the medicine took effect, the woman begged her family to kill her before her heart froze. Her family obeyed her. The woman’s sacrifice protected her family, but the medicine that cursed her changed the world forever.

Maybe the medicine took on a life of its own. Maybe its power was too great to be hidden. But one way or another, more monsters with frozen hearts began to appear in the world. The Mi’kmaq called these frozen-hearted monsters chenu.

When a person transforms into a chenu, the first thing to change is the heart: It freezes into a block of ice. A chenu keeps its intelligence but loses everything that makes it truly human. Gradually, the body of the chenu shrivels as its blood stops moving, and it becomes a walking mummy, prowling the night to eat unsuspecting travellers, or massing with others to attack and devour whole villages.

The time-honoured way to subdue a chenu is to chop it into pieces and melt its icy heart in the heat of three strong fires. But there is at least one other way to survive a chenu encounter: Use your brains and not your brawn. A long time ago, according to legend, a woman was spotted by a chenu. Unable to fight, she decided to gamble on her brains. “Grandfather! It’s so good to see you!” she shouted. She embraced the monster, which made it too confused to eat her. The woman kept treating the monster as her own grandfather until the charade took on a life of its own. The chenu developed a fatherly love for the woman, her husband, and her child — a heartwarming ending to a chilling tale.

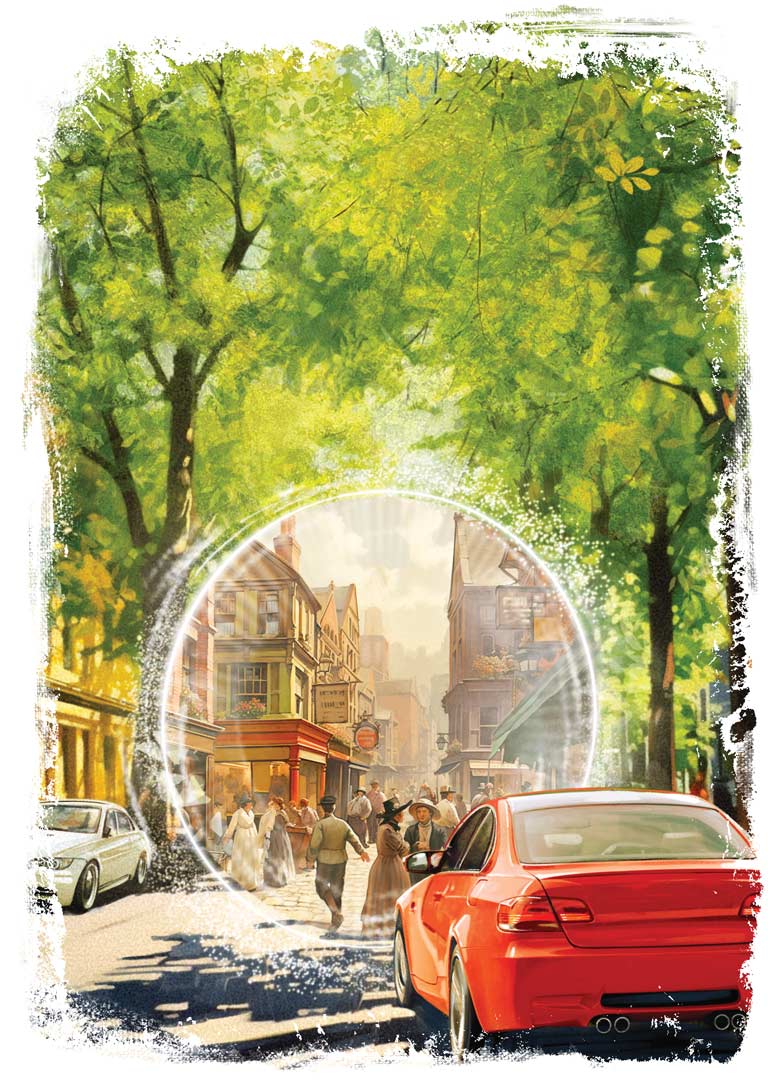

The Shelbourne Street Time Warp

Victoria’s Shelbourne Street runs seven kilometers south from Begbie Green to Mount Douglas Park. But there’s more to this street than parks, homes, and shopping malls. The street has history — literally. Shelbourne Street purportedly holds a time vortex.

According to local legend, drivers and pedestrians travelling down Shelbourne Street have suddenly found themselves on a dark, rural road lined with antique homesteads. Nearby residents have also been troubled by strange dreams of an ancient village. The popular explanation? A fissure in time. Believers contend that these travellers have temporarily crossed into a more rural Victoria of the 1800s.

To investigate the phenomenon, walk or drive along Shelbourne Street between Pearl Street and Ryan Street on an October night between 2:00 and 3:00 a.m., when legend says the time warp will appear. Unfortunately, journalists who have attempted to enter the time warp have found no success yet. However, that’s no reason to give up. Until time machines are invented, the Shelbourne Street time warp remains your best chance of breaking into the B.C. housing market.

The Toronto Tunnel Monster

Canada’s most-populous city is built on ravines, rivers, and creeks. As the town of York became the City of Toronto in the early nineteenth century, more and more land had to be claimed from the water to provide space for people to live. The city built an elaborate set of tunnels — complete with vaulted roofs, stone walkways, and artistic masonry — to divert the many creeks and streams into the sewer system, where they could drain into Lake Ontario.

In 1979, a fifty-one-year-old man named Ernest was looking for a missing kitten. He descended a fire escape on the side of his Parliament Street apartment building. At the bottom of the fire escape lay the entrance to a narrow passageway that led into one of Toronto’s hidden tunnels. As he crept through the tunnel by the light of his flashlight, Ernest saw something that wasn’t a kitten. The creature stood a metre tall, with long, skinny limbs. It was covered with grey fur and glared at him with red eyes.

“Go away!” The creature hissed. It bolted down the tunnel, away from Ernest. Ernest took the being’s advice and left the tunnel as fast as he could.

Since this sighting, the creature has never been seen again — at least not by anyone willing to share their story. However, Ernest’s 1979 encounter might not be the first time someone has witnessed this creature. Tunnel-monster enthusiasts have suggested that, given the buried streams flowing beneath the city, this sewer-dwelling sprite might be an urban version of a memegwesi: a small, hairy river spirit found in Ojibwe folklore.

Advertisement

The Burning Ship of Northumberland Strait

Northumberland Strait divided Prince Edward Island from the mainland of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. Its banks hold natural wonders like New Brunswick’s Kouchibouguac National Park, historic communities like Charlottetown, and culinary curiosities like Nova Scotia’s famous Pictou County brown-sauce pizza.

The strait is also the home of stories, told in all three provinces, of a mysterious maritime manifestation. The stories begin with a strange glow over the strait. Across the dark expanse of the sea, the terrifying source of the light gradually becomes clear: A sailing ship, completely ablaze, ploughs through the water at an incredible speed. The ship then either disappears, sails off, or sinks beneath the waves.

The flaming ghost ship of Northumberland Strait has been sighted for generations. While no one agrees on the origin of the burning ship, long-time residents of the Maritime provinces speak matter-of-factly of its existence.

The ship’s appearance is so widespread that skeptics have sought to demystify it since 1904, when William Francis Ganong posited a scientific explanation. According to Ganong, the apparition was caused by St. Elmo’s fire — a weather phenomenon in which glowing plasma is created by an electrical discharge from a rod-like object, such as a ship’s mast, in an electrically charged atmospheric field. Under the right conditions — such as a thunderstorm — any ship travelling through the strait could appear as a burning phantom ship. This would also explain why the burning ship sometimes appears with three masts, at other times with four, and — in one account — even appears as a steamship.

The Rougarou

Hearing a wolf howl at night is chilling. But that nocturnal call might come from something even scarier than a wolf: a creature known as a rougarou.

Rougarou, also spelled rugaru or roogaroo, is a Michif word originating from the French loup-garou, or werewolf. As the Métis people blended their Indigenous and European traditions, they also blended stories. French tales of werewolves melded with Métis shape-changing legends, leading to the figure of the rougarou.

While Métis stories are filled with humans changing into bears or other animals, rougarous are different. They are cursed to live as humans by day and as wolves by night. In some stories rougarous have become monsters for offending God, while in others they’re just born dark.

It’s hard to tell if a neighbour, friend, or loved one is a rougarou: In their human form, these shape-shifters can be male or female, tall or short, friendly or cruel. A rougarou is often discovered when a witness spots it in both forms and realizes the connection: In one story, a rougarou in its wolf form attacks a woman, who later finds a thread from her torn dress between a man’s teeth. In another story, a man accidentally hits a wolf with his car and notices his neighbour bruised and limping the next day.

Your best bet to identify a rougarou is by looking at its eyes: Some stories say that a rougarou’s human eyes are yellow and slanted, like a wolf’s. According to another story, these wily wolf men love playing poker. So, until you vet your friends, maybe avoid the next card game.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

The Chasse-Galerie

On Year’s Eve, most people scan the sky for fireworks. In Quebec, you might spot something else: a birchbark canoe tearing through the air, filled with bearded lumberjacks screaming in exhilaration — or is it terror?

The lumberjacks are on the legendary journey known as the chasse-galerie. The legend has roots in ancient French folk tales in which the souls of the damned go chasing through the night air. The specific name “chasse-galerie” may have come from a story of a nobleman named Gallery, doomed to flee through the sky after hunting on a Sunday instead of attending mass. In Quebec, Gallery’s chase, or la chassegalerie, merged with Indigenous myths of flying canoes to become a uniquely Québécois story.

According to the legend, any canoe can obtain the power to fly through a blasphemous ride-share scheme with the Devil. The riders simply make a deal for Satan to enchant their canoe, using their souls as collateral. The Devil, of course, has a catch: If the riders mention God, make the sign of the cross, or touch a church steeple, the canoe will fly them to Hell.

In Québécois tales, lumberjacks generally fly the canoe from their isolated work camps to their home villages for drinks and dancing. But trouble invariably follows on the return trip. Inevitably, the navigator of the vessel (sometimes the Devil himself in disguise) breaks, or comes close to breaking, one of the three rules, and the paddlers are put in peril of eternal damnation.

In Honoré Beaugrand’s 1900 book La chasse-galerie, légendes canadiennes, anyone who wants to try their luck on the flying canoe simply says the magic words, “Acabris, Acabras, Acabram! Fais nous voyager par-dessus les montagnes!” — or, presuming the charm also works in English, “Acabri, Acabra, Acabram! Make us travel over top of the mountains!”

The Fairies of Newfoundland

When British and Irish colonists arrived in Newfoundland, they brought with them stories of a folk they called “Them”— also known as the fairies.

No one knows if the colonists found new fairies when they arrived, or if the fairies came along with them. Regardless, Newfoundland’s fairies have an edge. They can appear as people, as animals, or, sometimes, not at all — manifesting as a gust of wind or an uneasy feeling. Angry fairies have been said to strike children with invisible whips. When children fall sick after such a whipping, folk tales say that doctors with scalpels have found fish bones, fabric, and straws of grass beneath their skin.

One recurring legend describes a unique form of identity theft: Fairies abduct a victim and send a look-alike home in his or her place. While the victim’s family is relieved at first at the loved one’s return, the doppelganger seldom speaks and never, ever eats. Invariably, a wise man or woman recognizes the fake for what it is and drowns or burns the imposter, allowing the real person to return home.

Some storytellers on the Rock say that fairies dislike electricity, which is why they don’t bother people as much in modern times as they did in the past. So, if you venture into the woods, make sure to bring aling your gadgets.

Advertisement

The St. Louis Light

The village of St. Louis, Saskatchewan, hugs a picturesque bend of the South Saskatchewan River. While the town of four hundred mostly stays out of the news today, its historical roots run deep: The Northwest Resistance of 1885 was fought only a few kilometres away, and the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway ran through the town, crossing the river on an iconic rail bridge. Some say the history of the Grand Trunk never left St. Louis.

Even though the rail line was discontinued in 1988 (after being taken over by Canadian National in 1923), residents have spotted a phantom light travelling down the tracks north of St. Louis for decades. Some say it’s the ghostly headlight of a long-ago train that killed an unfortunate conductor who was inspecting the tracks. Bafflingly, the light has continued to appear, even after the tracks along that section were removed.

While skeptics believe the mystery is caused by the diffraction of car headlights from a distant roadway, believers point out that the phantom light has been reported since at least the 1920s, when few people had cars in northern Saskatchewan. If you’re really, really sure that the St. Louis light is just an illusion, you can put your certainty (or bravery) to the test: An unwritten rule of the St. Louis light is to never stand or park a car in its path. Doing so prompts strange electrical malfunctions in nearby vehicles and devices.

Sasquatch

The hairy hominid from the west coast needs no introduction. Its shaggy frame has (allegedly) been captured on film, described in breathless stories, and sought through binoculars, telescopes, and videocamera lenses across the foggy mountain forests of the Pacific Northwest. Early settlers knew it as Bigfoot, but in modern times we call it sasquatch.

The word “sasquatch” is an English rendering of various words found in the Salishan language family, including sasq’ets in Halkomelem, Ts’emekwes in Xwlemi Chosen, and sc̓wanáytm in Nsyilxcən. Across the many First Nations of the Pacific Northwest, the being that settlers identify as sasquatch figured as a more-or-less-benign wild man, sometimes wielding supernatural powers or bearing spiritual significance. When settlers heard these stories, they adopted their own beliefs about this reclusive forest dweller, suggesting it might be a descendant of Neanderthals or a previously unidentified giant ape.

Sasquatch’s popularity in the Western imagination exploded after Americans Roger Patterson and Robert Gimlin released a short film clip in 1967 that showed what appeared to be a large, hairy primate strutting through the California forest. Inspired by the film and by reported sightings of a tall, bellowing creature in the woods, entire subcultures developed that persist to this day, dedicated to proving the creature’s existence.

Which leads to the question: When a creature’s likeness has appeared in more than sixty movies, several video games, and countless amateur videos; when a creature has caused thousands of people to take up “squatching” to hunt for proof of its existence; and when the word “sasquatch” immediately conjures a mental image in a listener’s mind, does it really matter whether the flesh-and-blood-and-shaggy-hair being actually exists?

All legends come, in part, from the human imagination’s grappling with the unknown. They are an ancient vehicle for human discovery, and they can take us to surprising places and accomplish amazing things. Some, like the stories of the chasse-galerie and the rugarou, come from the crashing together of different cultures; their existence might provide a common language that two communities need to become one new community. Others, like the tale of the chenu, distill moral lessons that can provide guidance to those who hear them. The legend of sasquatch — and all the others recounted here — shape our cultures and our behaviours. Measured by their impact on the world, that makes these legendary beasts, beings, and phenomena more real than most people — even the exceptionally hairy ones.

We hope you will help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement