Sorcery in New France

In the 1660s, New France was a frightening place. Its tiny population of about 3,200 French settlers lived in constant terror of raids carried out by the fearsome Iroquois League. Jesuit missionaries were taken captive, tortured, and killed. Deadly epidemics raged. And everywhere, it seemed, there were omens of more calamities to come.

“The earthquake that happened last winter in Montreal made the settlers tremble in advance, causing them to dread the misfortunes which followed that baleful omen,” said the 1660–61 edition of the Jesuit Relations.

“The lamenting voices that were heard in the air over Trois-Rivières might have been the echo of the poor captives carried away by the Iroquois; and the canoes that seemed to be flying in the air, all on fire, around Quebec, were only a feeble presage of the enemies’ canoes.”

At around the same time, the Ursuline nun Marie de L’Incarnation also wrote of disturbing voices heard in the air and a fiery canoe in the sky, as well as other strange phenomena.

“What’s more,” L’Incarnation wrote in a letter to her son, “it was discovered that there are sorcerers and magicians in this country.”

L’Incarnation observed that the strange events started happening after the arrival in 1660 of a ship carrying new colonists. Among the passengers was sixteen-year-old Barbe Hallé (also known as Halé, Hallay, or Haly) and a man named Daniel Vuil, a Protestant-born Frenchman who had seemingly converted to Catholicism during the voyage.

According to L’Incarnation, during the overseas journey Vuil had tried to seduce Hallé but was refused. After settling in Beauport, near Quebec City, Vuil carried on his trade as a miller, and Hallé went to work as a servant in a manor house.

In December of that year the manor house suddenly fell prey to strange phenomena. According to Jesuit missionary Paul Ragueneau, “the girl’s home was so infested that stones were flying from all sides, thrown by invisible hands, hurting no one, though they flew through twenty persons or so, with a noise and a force as great as if they had been launched by a mighty arm.”

The young servant soon experienced demonic visions: “Only the possessed girl saw the demons who appeared to her under various shapes of men, women, children, beasts and hellish spectres, and, at last spoke through her mouth … without seemingly using the possessed girl’s voice,” wrote Ragueneau.

First, local people thought that the house was haunted. Hallé was moved to another place, but to no avail. The case came to the attention of François de Laval, the bishop of New France, who ordered an exorcism. When the local priest had no luck expelling the demons, Laval came in person to try exorcising them himself. The bishop was no more successful. Stones continued to fly.

Hallé was finally moved to the colony’s hospital, l’Hôtel-Dieu de Québec, which was run by a convent that housed Catherine de Saint-Augustin. Mother Catherine knew something of demons. Widely revered as the holiest woman in New France, she had allegedly been “obsessed with the devil” since the 1650s. Demonic obsession, as opposed to possession, meant that she was a victim of attacks by demons but remained in control of herself.

According to Ragueneau, “various figures, either to fool her, either to scare her; sometimes they would shake her bed during the night; other times they would act on her tongue or other parts of her body to keep her from praying aloud, confessing, receive communion, take holy water or make the sign of the cross.”

In trying to heal Hallé, Catherine de Saint-Augustin reportedly invoked the wrath of the girl’s evil spirits. “Those unhappy demons, unable to intimidate her with all their threats, tried to surprise [de Saint-Augustin] by changing themselves into angels of light, in order to delude her,” wrote Ragueneau.

In the meantime, the colony’s authorities came to the conclusion that Hallé’s demons had been brought on by her fellow traveller on the ship from France — Daniel Vuil, her would-be suitor. They took as proof the fact that the girl said he had started appearing to her. Though nobody could see the spectre except Hallé, Vuil was nonetheless arrested.

In Marie de l’Incarnation’s view, the man was a wizard. Facing the girl’s refusal of his advances, Vuil would then have decided “to achieve his ends through the ruses of his diabolical art,” she wrote. Witchcraft was not the only reason authorities had for arresting Vuil.

Bishop Laval had travelled on the same ship as Vuil and Hallé and was convinced that he had converted Vuil to Catholicism during the crossing. Yet, once in Canada, it was discovered that Vuil was still a Huguenot. In the eyes of the Catholic Church, that made him a “relapse,” a very grave offence punishable by death in those days of religious intolerance.

Yet another reason for fingering Vuil was that he was accused of selling liquor to local First Nations people. This contravened an edict then recently adopted by the governor and rigidly enforced by Bishop Laval, who excommunicated those who indulged in the traffic. Protestant, accused of being a relapse, an alcohol trafficker, and a witch — things really did not look good for Daniel Vuil.

Indeed, Vuil was “arquebused” (shot) on October 7, 1661, in Quebec City. In the absence of documents related to his trial, the exact reason for his execution is unclear and remains a topic of debate for historians.

The usual punishment for witchcraft in New France was banishment, not death.

Historian André Vachon said the real reason for his execution was that he sold alcohol to Aboriginal people. At the time, the colony traded with the Algonquins, Montagnais, Huron, and other groups. Others have argued that liquor trafficking was not at that time an offence punishable by death; but religious offences such as blasphemy and profanation were.

According to historian Vincent Grégoire, he was mostly likely shot for returning to the Protestant faith after his alleged conversion to Catholicism by Bishop Laval. In any event, he was not buried in a Catholic cemetery, and his exact resting place is unknown.

After Vuil’s death, Hallé continued to be plagued by demons for some time. Finally, in 1662, Catherine de Saint-Augustin found a novel way to protect the youth from demon attacks — she had her sewn into a bag. Whatever the rationale, this, combined with the allegedly miraculous intercession of the spirit of Jesuit martyr Jean de Brébeuf, seemed to have worked. Hallé eventually recovered her health.

She left the convent and led a normal life afterward, marrying a man named Jean Carrier in 1670 and dying in 1696 at age fifty-two, a respectable lifespan for the time. The incident involving Vuil and Hallé stands out for being relatively uncommon in New France.

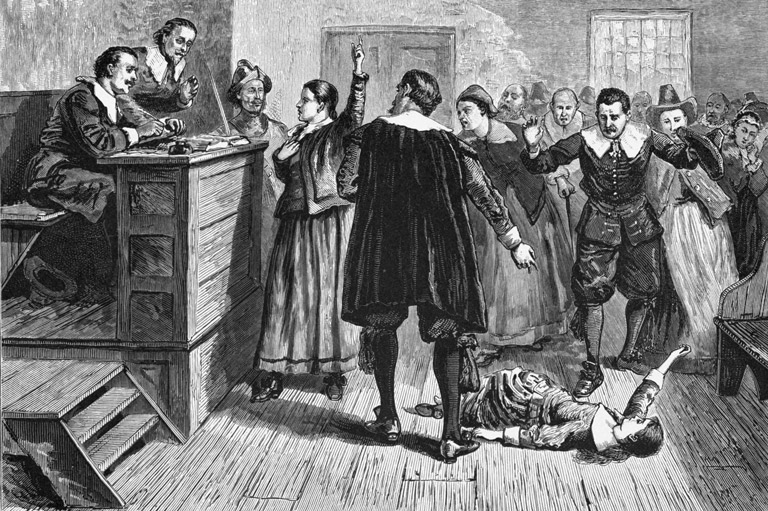

Three decades later, in neighbouring New England, witchcraft hysteria culminated in the Salem witch trials of 1692. A total of two hundred people, most of them women, were put on trial in Salem, Massachusetts, and twenty were executed.

Witch hunts never reached this level in New France. Cases in which people were accused of being in league with the devil were few and far between. One incident involved Montreal innkeeper Anne Lamarque, who was formally accused of witchcraft in 1682.

Witnesses testified that she possessed a book of magic and spells. In her defence, Lamarque stated that it was a treatise on herbs and medicine. Protected by high-placed friends, she was acquitted, barely escaping the sentence of banishment.

In New France, where men greatly outnumbered women, there was more than one case in which a man was accused of putting a curse on a woman who had spurned his marriage proposal.

In 1657, René Besnard dit Bourjoly was convicted of placing a sterility spell on both the woman who had turned him down and her new husband. The couple was unable to have children, and their marriage was eventually annulled due to “perpetual impotence caused by magic.” Bourjoly’s punishment was banishment from the colony.

As for Catherine de Saint-Augustin, she remained in poor health and was reportedly besieged by demons of all sorts until her death in 1668. After she died, Ragueneau published her biography, making public the saintly woman’s struggles with demons.

However, the reaction of the church was lukewarm. This kind of mysticism had started to go out of fashion, thanks in part to a new kind of rational thinking, influenced by philosopher René Descartes and others, that was then shaking up Europe.

In 1682, a French royal ordinance laid the groundwork for decriminalizing witchcraft; it mentioned “alleged witches” and considered them blasphemers or charlatans but made no reference to their supernatural powers. The last execution of a witch in France took place in 1718.

In the whole Western world the witch-hunting craze that had claimed thousands of lives since the early 1500s was receding. Even the Salem affair of 1692 stands out as an exceptionally late case. New France had been relatively spared of it — but not completely, as the case of Barb Hallé and Daniel Vuil shows.

Enchanted Flying Canoes

From the very beginning of settlement in New France, tales of bewitched canoes flying through the air were part of folklore. Their origin was a combination of an Indigenous legend about a flying canoe and a folk tale from France about a hunter condemned to be chased through the night skies for eternity because he went hunting on a Sunday during High Mass.

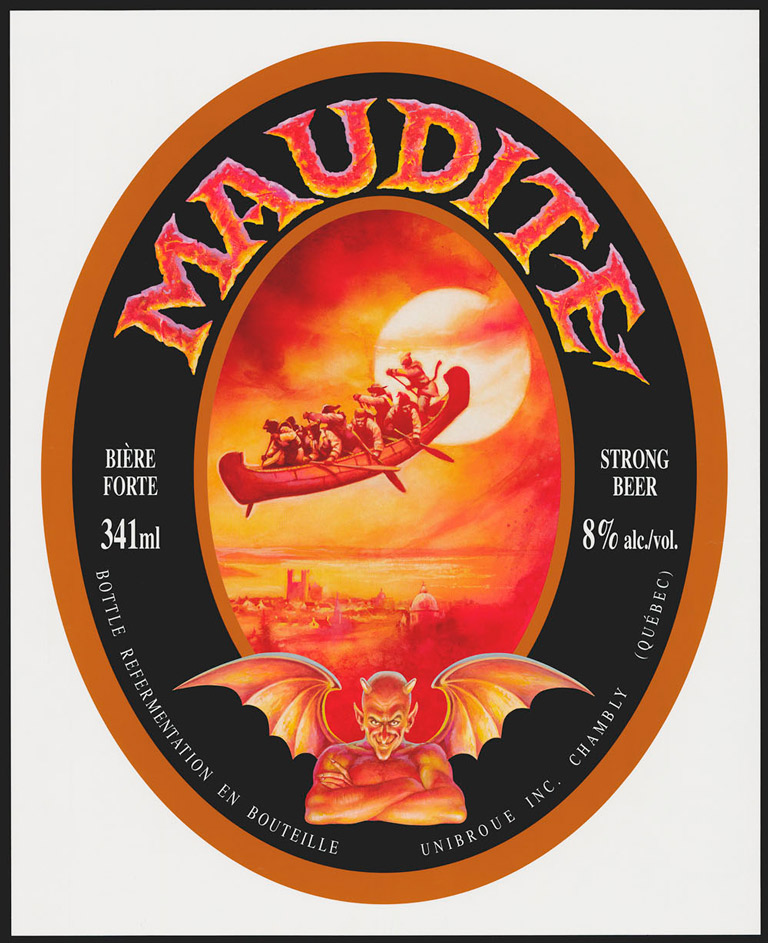

Over time, homesick coureurs de bois and voyageurs adapted the tale to suit their needs. A well-known version known as “La Chasse-galerie” was written by Honoré Beaugrand in 1892. In this story, woodcutters make a deal with the devil to quickly fly home to their sweethearts on New Year’s Eve. But if they mention God’s name or touch a church steeple, the devil will possess their souls.

The men arrive home and attend a party, dancing all night long. The next morning, while flying back in their magic canoe, the drunk navigator just misses a church steeple and swears. Fearing they will lose their souls, the others tie the drunkard up. Meanwhile, the canoe crashes into a tree and its occupants are knocked cold. They eventually wake up in their beds, unhurt.

Today, the story lives on in the label of a brand of strong dark beer from Quebec. Maudite (damned) beer from Unibroue was launched in 1992. The brewery used the image from “la Chasse-galerie” to convey the idea of a deal with the devil, because it was the first strong beer (eight per cent alcohol content) to be sold in Quebec supermarkets.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!