Full of Hope and Promise

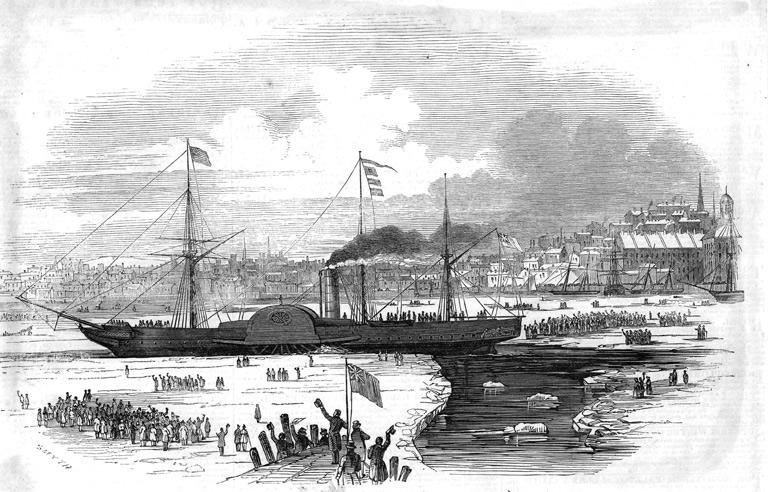

Charles Dickens was afraid to turn in. That morning in Liverpool, he and his wife, Catherine, had boarded the steam packet Britannia, bound for Boston, and now, despite the general air of festivity on board, Dickens viewed the upcoming 12-day run across the North Atlantic with dread. He crept below deck at midnight and found his wife already in “silent agonies.” The writer soon felt a chill — the beginnings of the seasickness that confined him to the cabin for the duration of the voyage. It was early January 1842; the couple had just celebrated Christmas in London with their four young children and would be away from home for almost six months while they toured America.

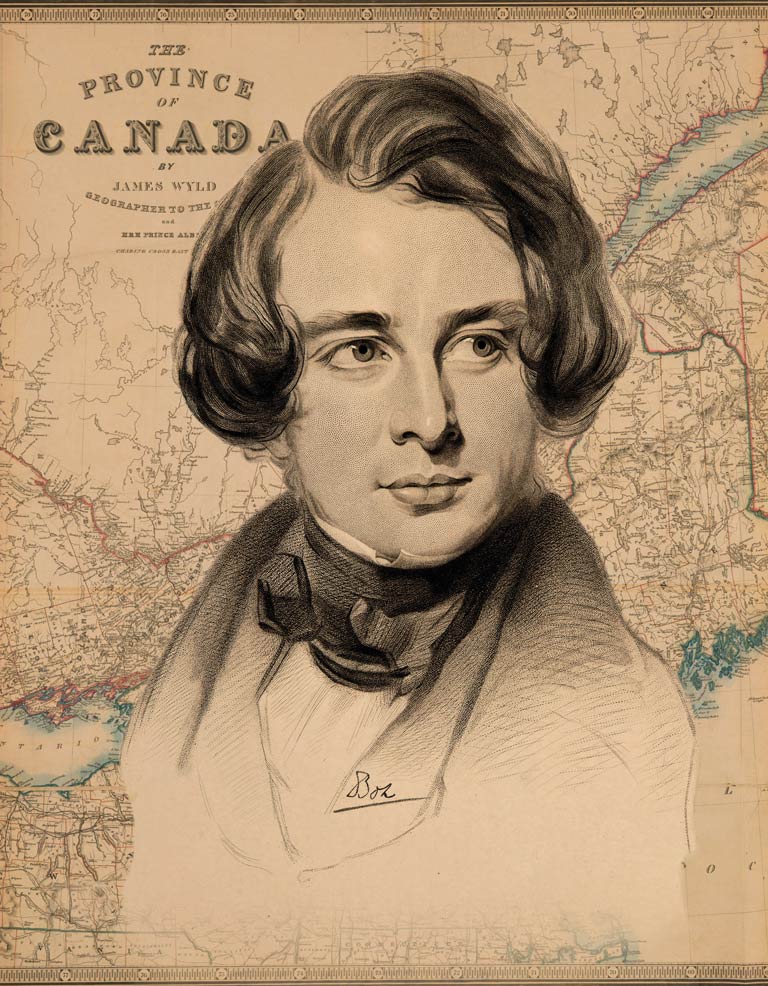

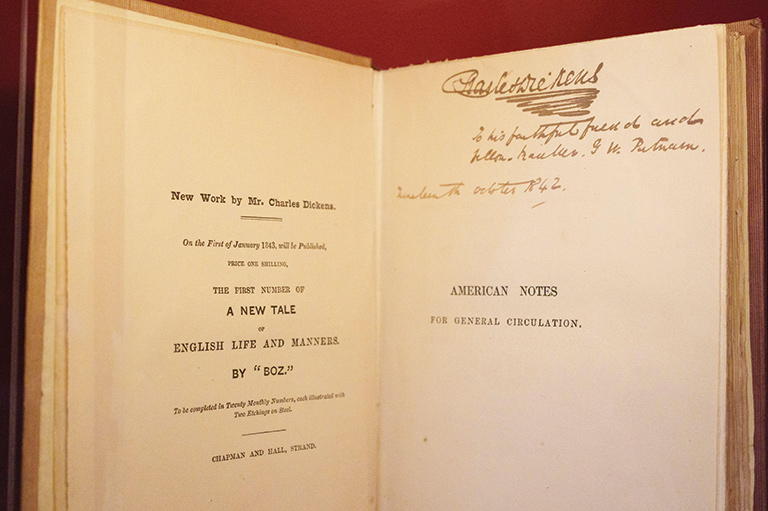

Dickens was just shy of 30 when they embarked, and it had been six years since he’d published his first book, Sketches by Boz, a collection of essays, short stories and sketches that came out under the pen name “Boz.” Dickens soon turned his hand to longer fiction, and by the time he went to America, he’d authored five novels, including The Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist and Nicholas Nickleby. Now, he felt, it was time to write something in a different genre.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

For almost a year, he’d toyed with the idea of visiting the U.S. to produce a travel narrative. Bookshops did brisk business in volumes of Englishmen’s impressions of America, and he was eager to tour the young republic and add his story to shelves. His reportage and fiction were animated by a deep interest in social inequality, legal systems and political institutions, as well as a desire to remedy abuses, and he foresaw that the U.S. would offer him a fertile field for these preoccupations. Dickens was right; American Notes for General Circulation, the resulting narrative, instantly became a classic of the genre.

Less well known is that Dickens’ visit to America included a substantial Canadian sojourn. The portion of the trip that took him north of the border has always been overshadowed by his time in the U.S., both in the published travel narrative itself and in subsequent writing about the author. Although Charles and Catherine spent about six weeks in Canada, the colony is described in a mere half chapter of the 18-chapter American Notes (a “brisk account of some Canadian cities,” as Sacheverell Sitwell writes in his introduction to a modern edition of the book), and the episode merits a scant three pages in Peter Ackroyd’s magisterial 1,000-page biography, Dickens.

But the Canadian visit was a significant episode, both for Dickens personally, as it served as a respite and counterpoint to his grand public tour of the U.S., and as a historical testament to the state of the colony in a pivotal period in its development. In fact, Dickens set foot in British North America even before he arrived in the U.S., when the Britannia slipped into Halifax to deliver and pick up mail. On Jan. 19, as the steamship approached the Eastern Passage, it ran aground on a bank of mud. Dickens recounts how an officer piloted a boat to the shore and returned with “a tolerably tall young tree, which he had plucked up by the roots” to prove that land had been reached.

The next morning, the ship steamed into Halifax Harbour, and Dickens soon received a taste of the adulation that would await him in the United States. Joseph Howe, speaker of the Nova Scotia House of Assembly and future premier, jumped aboard, calling Dickens’ name and hauling him off to the city. Referring to himself with one of his favourite nicknames, Dickens later writes to his close friend (and later biographer) John Forster, “I wish you could have seen the crowds cheering the inimitable in the streets … judges, law-officers, bishops, and law-makers welcoming the inimitable.” The writer attended the opening of Nova Scotia’s Assembly in Province House and remarked on the affinity between British North America and his mother country, noting that the British Parliament’s forms were followed so closely “that it was like looking at Westminster through the wrong end of a telescope.”

After a seven-hour layover, Dickens continued on to the main purpose of his trip. He began with a tour of the Eastern Seaboard, making his way through Boston, New York City, Philadelphia and Washington, D.C., to great acclaim, and satisfying his interest in public institutions, industrial development and forms of government. In Washington, Dickens made a key change in his travel plans; to avoid the “contemplation of slavery,” he reoriented himself west, rather than south. The couple travelled by canal boat and paddle steamer to Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, St. Louis and the Illinois prairie, where they saw the rapid opening of the midwestern states. But they grew increasingly weary and homesick, and by mid-April, it was time to turn back east and make their way to British North America. Tellingly, as Dickens recounts that decision, he states, “we were moving towards Niagara and home.”

Dickens excused himself from drawing any comparisons between the U.S. and the British colonies in Canada, stating in American Notes, “I shall confine myself to a very brief account of our journeyings in the latter territory.” He gives the impression of a man exhausted by his travels, disillusioned by what he had seen, and seeking rest and respite. Paradoxically, as he travelled by train to what he called the “English side” of Niagara Falls, he entered a land that was being transformed.

Advertisement

Five years before Dickens came to British North America, Upper Canada and Lower Canada had endured violent rebellions against the Tory political order. In their aftermath, an Act of Union brought the Canadas together as the United Province of Canada, and the inaugural election for the colony’s new legislature was held the year before the couple’s visit. A network of British Army garrisons maintained order and Dickens noted that “British officers … form a large portion of the society of every town.” As he and Catherine travelled through Canada, they moved in the orbit of these posts, often hosted and feted by their officers. French Canadians were seen from a distance, and Indigenous Peoples not at all.

Niagara was Dickens’ base for 10 days, time spent in contemplation of the falls, which he viewed from different locations and in a variety of weather conditions. In the roaring shadow of the great cataract, Dickens found calm and tranquillity and recovered a sense of his inner life. For the weary author, Niagara was “Enchanted Ground,” where, according to Ackroyd, he regained “that peace of wonder and self-communing that had been snatched from him in America.”

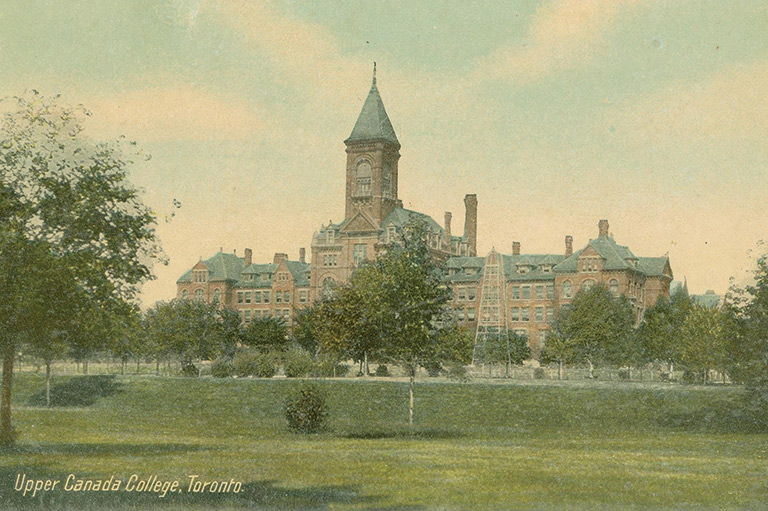

From Niagara, the couple proceeded downstream to Queenston, Ont., where they saw the ruined Brock’s Monument, which a disgruntled former rebel had recently blown up. A steamboat took them across Lake Ontario to Toronto. Dickens found the city “full of life and motion, bustle, business and improvement,” and compared it to a thriving English country town. He commented approvingly on Upper Canada College, the “good stone prison” and newly opened University Avenue, and was the guest of honour at a banquet thrown by John Beverley Robinson, chief justice of Canada West and key member of the Family Compact.

But Dickens also lamented Toronto’s rampant political and religious sectarianism, as Tory faced off against Reformer, and Protestant against Catholic. In a letter to Forster, Dickens confides, “The wild and rabid Toryism of Toronto is, I speak seriously, appalling.” In American Notes, he recounts an incident that had occurred during the inaugural election for Canada’s Legislative Assembly in 1841. Toronto’s two Tory candidates had been defeated by a pair of Reformers, and during the victors’ celebratory parade on King Street, shots had been fired into the crowd from the Coleraine Inn, killing a man. The murder was unsolved, and Dickens alludes to the allegiance of the assailant with an oblique reference to the flag that had shielded him from being apprehended: “Of all the colours in the rainbow, there is but one which could be so employed; I need not say that the flag was orange.”

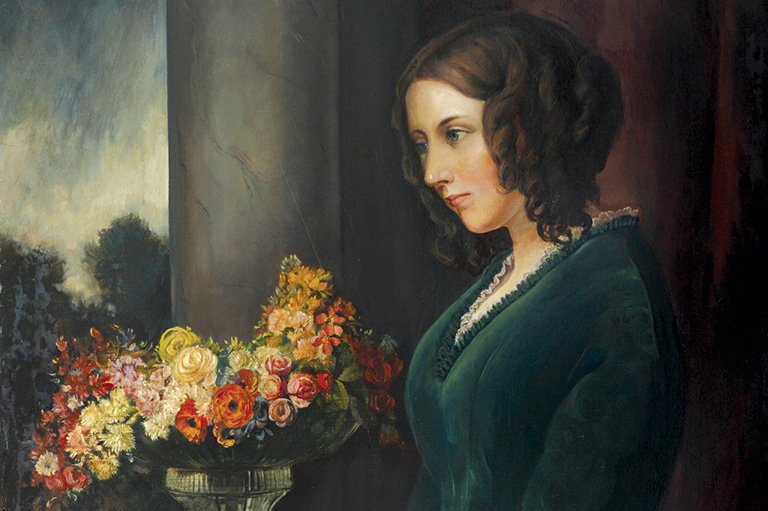

Dickens fed his interest in criminal justice during their next stop: Kingston, Ont., the new capital of the Province of Canada. He visited the penitentiary, where he met with a young female rebel who had been imprisoned for horse theft during the rebellion. The novelist was clearly taken with this figure with “quite a lovely face” who, often disguised as a boy, had borne secret messages across the Niagara River and who now looked out at him through her prison bars with “a lurking devil in her bright eye.”

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Travelling via steamboat and stagecoach, the couple then made their way down the St. Lawrence to Montreal. As he approached the city, Dickens looked out upon a “pleasant and well-cultivated country, perfectly French in every respect,” noticing French signs, wayside shrines and crucifixes, clergy in the streets, and the bright-red sashes of the men and widebrimmed straw hats of the women. He and his wife spent almost three weeks in what was then Canada’s largest city, lodging at Rasco’s Hotel (still operating as Maison Rasco), but Montreal leaves little trace in American Notes. Dickens admired Notre-Dame Basilica, then under construction, with “two tall spires, of which one is yet unfinished,” and noted that immigrants grouped by the hundreds on the public wharves, but his attention was soon drawn beyond sightseeing, as he rekindled his love of the theatre. The author threw himself heartily into the life of the Garrison Amateurs, a troupe made up of officers of the British military post at Montreal. Dickens not only served as director, prop manager and set designer but also took the stage himself. A set of three plays was performed on two nights — two light comedies, A Roland for an Oliver and Past Two O’Clock in the Morning, and a farce, Deaf as a Post, in which Catherine Dickens took on a minor role.

Their Montreal stay was broken by a brief excursion to Quebec City, where Dickens was “charmed by its interest and beauty.” As he toured the old city, cliffs and Plains of Abraham, he recalled the events of the 1759 battle and was especially taken by the Wolfe-Montcalm Monument, “[w]hich perpetuates the memory of both brave generals.” In American Notes, the visit to Quebec concludes with a picturesque description of the countryside along the St. Lawrence, viewed from the former Parliament Building of Lower Canada, and this “brightest and most enchanting picture” serves as a fitting bookend to the view of Niagara with which the Canadian tour had begun.

Leaving Montreal at the end of May, Dickens and his wife took Canada’s first railway to St-Jean-sur-Richelieu. There, the British officers of the local garrison saw them off, before they travelled by steamboat down the Richelieu River and into Vermont. As he steams across the boundary, Dickens concludes with a paean to the rising country, lauding a nation “advancing quietly; old differences settling down, and being fast forgotten; public feeling and private enterprise alike in a sound and wholesome state; nothing of flush and fever in its system, but health and vigour throbbing in its steady pulse; it is full of hope and promise.”

Canada had brought health and vigour back to Dickens himself and provided the writer and his wife with an interlude of much-needed relief from the trials of American travel. By the end of June, they were back home in London, reunited with family and friends. At Dickens’ insistence, they travelled home under sail, rather than by steam.

A Final Note

Dickens’ travel narrative, American Notes for General Circulation, with its criticisms of slavery, mob rule, violence and vulgarity, was published in October 1842. He followed that with his sixth novel, Martin Chuzzlewit, which began to appear in serial form in December. Even more than American Notes, this work, with its unflattering portrait of American frontier society, led to deep and lasting resentment in the U.S. By 1867, the year of Canadian Confederation, feelings in the U.S. had softened enough that Dickens was able to return for a second, triumphant tour of northeastern cities. Aside from a brief excursion from Buffalo to Niagara Falls, Canada was not included on the itinerary.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Related

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement