Controlling Customs

Bundling: Premarital Permission

We tend to generalize nineteenth-century sexual mores as being pathologically straight-laced. While on the surface this may have been true, a little-known courtship ritual from the Canadian backwoods serves to challenge this popular perception. This custom, particular to the labouring poor, was known as “bundling.”

An Upper Canadian journalist cautiously attempted to describe it in 1824 in the Colonial Advocate: “Common in some parts of the Canadas … A young man visits a young woman to court her for marriage and is allowed to sleep with her, each keeping on a part of their clothes.” Indeed, bundling actually took place in the young woman’s house, with her parents’ permission.

In an era when courtship was a closely monitored public display, bundling offered the betrothed couple a modicum of privacy that they would otherwise not have enjoyed. Such privacy permitted young couples to develop a personal intimacy and experiment with sexual compatibility. It was firmly expected, however, that erotic contact would halt prior to intercourse.

Constance Backhouse argues in Petticoats and Prejudice that bundling provided a measure of protection to young women. “When sexual intimacy took place in her parents’ house, with her parents’ knowledge, a young man could be held accountable for his actions.”

Thus, if a couple bundled out of control and pregnancy resulted, mom and dad could conveniently rush the betrothed pair into an emergency wedding. The genius of bundling is that it remained private. Even in the atypical scenario when it got out of hand, couples and their families could keep face in their communities without anyone being the wiser.

However, two bundling scandals in Upper Canada in the mid-1820s created an outraged public sensation. Both cases, which went to trial, involved young men who had abused their bundling privileges, impregnated their female suitors, and then refused to marry them.

During the Niagara bundling fiasco of 1824, a court reporter for the Colonial Advocate denounced bundling as “a disgrace to the country.”

If only the girl and her probundling family had “lived where an evangelized priest was made manifest, I am convinced that the disclosures she made … would never have shocked the ears of a Niagara audience.”

By the mid-1820s, however, it appears that bundling was in decline.

Though another bundling debacle would disgrace Upper Canada again the following year, the press alleged in 1824 that “the custom is, very deservedly, fast passing away.” Backhouse attributes this ostensive shift to the mounting pressures of evangelical reformers, lending substance to the Colonial Advocate’s contention.

Religion notwithstanding, we must consider that, given the decidedly private nature of bundling, it would be difficult to accurately trace the custom’s demise.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Charivari: Postmarital Censure

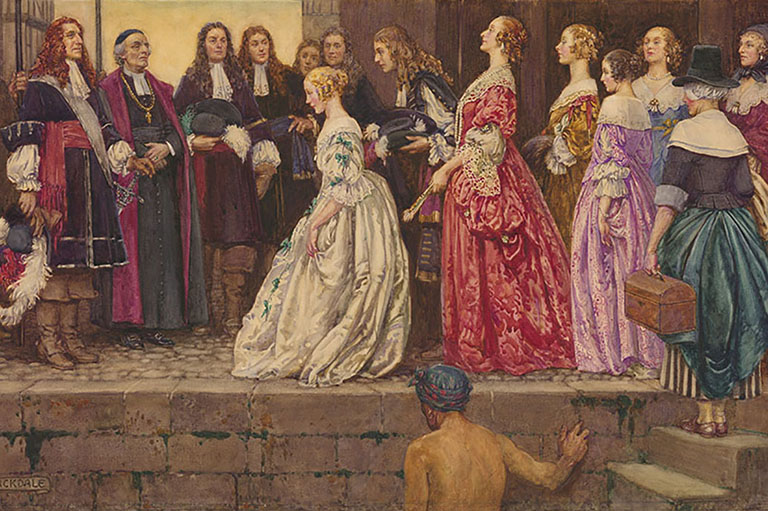

If a marriage offended public opinion, from the early days of New France well into the twentieth century, Canadians voiced their disapproval through the obstreperous and humiliating ritual of the charivari.

Charivaris were generally aimed at specific matrimonial faux pas: the widow who remarries only a few weeks after her late husband’s funeral; the octogenarian who takes a youthful bride; the fresh-faced opportunist who marries himself into the fortune of an aging spinster.

While it may never have been against the law to be a dirty old man or an avaricious social climber, such behaviour gravely offended the unwritten laws of acceptable social conduct. It was thus up to the boisterous participants of the charivari to wield the gavel of popular justice and put the guilty parties in their place.

The ritual itself possessed a marked element of the carnivalesque. Blowing on horns, sawing cracked fiddles, clattering skillet lids together, and banging out vicious tattoos on tin pots and copper kettles, the whole of the outraged citizenry would assemble in a nocturnal display before the newlyweds’ house.

If the noise-bombarded couple dared to peer out through the bedroom curtains, they would have beheld a most frightful spectacle.

As Susanna Moodie described it in 1852 in Roughing It in the Bush, the torch-lit antagonists disguised themselves in strange, ritualistic costumes, “putting their clothes on the hind part before, … wearing horrible masks, with grotesque caps on their heads, adorned with cocks’ feathers and bells.”

The crowd would then bang fiercely on the door, insisting that the couple pay the price of a peaceful honeymoon by furnishing the crowd with whisky, entertainment, or a sum of money for charity—sometimes as much as £100.

Once the fee was paid, the humbled newlyweds were pardoned of their improprieties and the charivari was finished. But if the couple refused to pay, the crowd would return again and again every night until the fee was extorted.

Indeed, if charivari victims chose to resist the demands of the crowd, they were often met with varying degrees of violence. Queen’s University social historian Bryan D. Palmer writes, for example, about an adulterous Ontario lawyer who, trying to flee the popular justice of his neighbours in 1868, was seized, manhandled, and hurled over a fence.

Furthermore, when a remarried Montreal widower, one Mr. Holt, defiantly called in the authorities to oppress his charivari of 1823, the crowd smashed all his windows and ransacked his house.

Worse still, out on the Ontario timber frontier in 1890, a gang of drink-sozzled lumberjacks charivaried the shanty of William Misner, who, they charged, had stolen another man’s wife. Tearing the shingles off his roof and breaking down his door, the woodsmen shot Misner to death when he tried to resist.

It appears, however, that most targets of the charivari wisely chose to swallow their pride and capitulate to the dictates of the crowd.

While that old British North America Act chestnut of “peace, order, and good government” typically characterizes Canadian political culture, the charivari suggests that when it came to asserting moral standards for marriage, only the politics of rowdiness would do.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!