Lost Generations

-

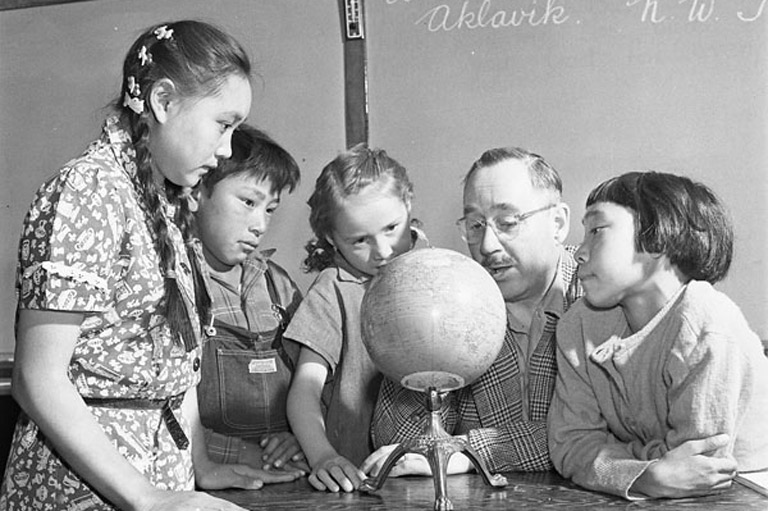

Mary Carpenter, far left, and her fellow students at All Saints Anglican School in Aklavik, Northwest Territories, receive a geography lesson in 1953.George Hunter/National Film Board of Canada. Photothèque/Library and Archives Canada/PA-180737

Mary Carpenter, far left, and her fellow students at All Saints Anglican School in Aklavik, Northwest Territories, receive a geography lesson in 1953.George Hunter/National Film Board of Canada. Photothèque/Library and Archives Canada/PA-180737 -

Mary Carpenter removes baked goods from an oven at All-Saints School, Aklavik, Northwest Territories, circa 1950s.Courtesy of Mary Carpenter / Library and Archives Canada

Mary Carpenter removes baked goods from an oven at All-Saints School, Aklavik, Northwest Territories, circa 1950s.Courtesy of Mary Carpenter / Library and Archives Canada -

Frank Carpenter (bent over), Mary's brother, and Merle, his adopted son, at Sachs Harbour, Banks Island, N.W.T.Courtesy of Mary Carpenter / Library and Archives Canada

Frank Carpenter (bent over), Mary's brother, and Merle, his adopted son, at Sachs Harbour, Banks Island, N.W.T.Courtesy of Mary Carpenter / Library and Archives Canada -

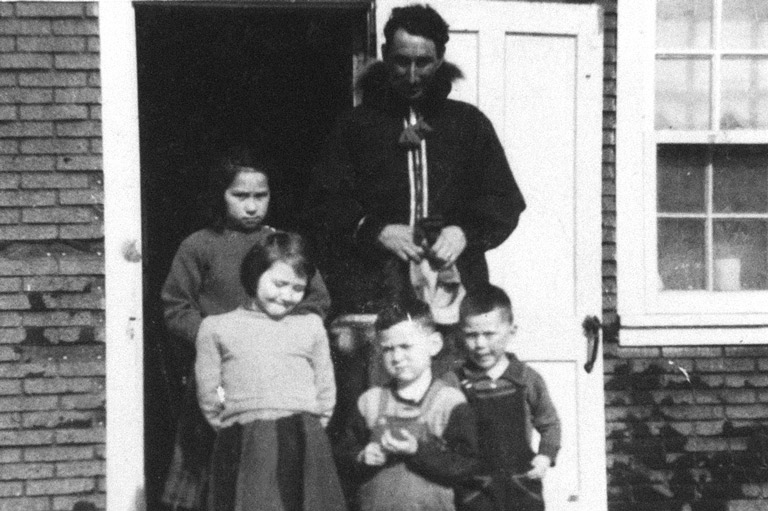

Fred Carpenter with his children, including Mary, who is wearing a skirt and light-coloured shirt.Courtesy of Mary Carpenter

Fred Carpenter with his children, including Mary, who is wearing a skirt and light-coloured shirt.Courtesy of Mary Carpenter -

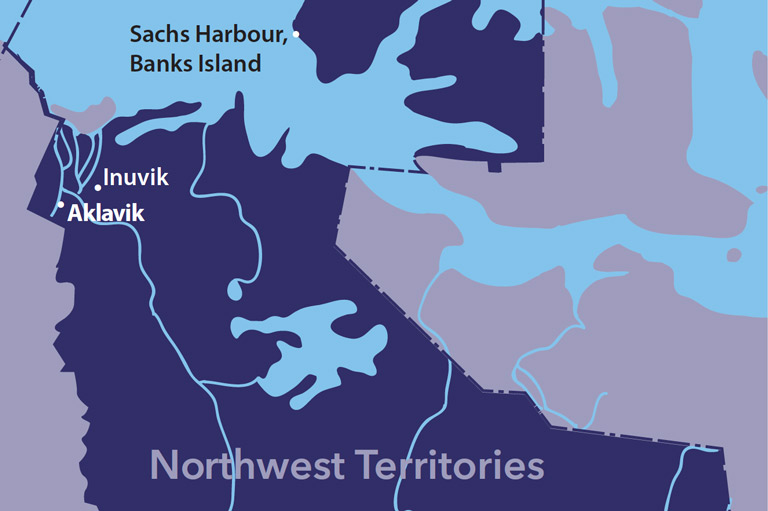

A map of the Northwest Territories shows the distance — about 555 kilometres — between the Carpenter family's home at Sachs Harbour on Banks Island and Aklavik, where Mary and her siblings attended residential school.Canada's History

A map of the Northwest Territories shows the distance — about 555 kilometres — between the Carpenter family's home at Sachs Harbour on Banks Island and Aklavik, where Mary and her siblings attended residential school.Canada's History -

Aklavik Roman Catholic school and hospital, circa 1943.Northwest Territories Archives

Aklavik Roman Catholic school and hospital, circa 1943.Northwest Territories Archives -

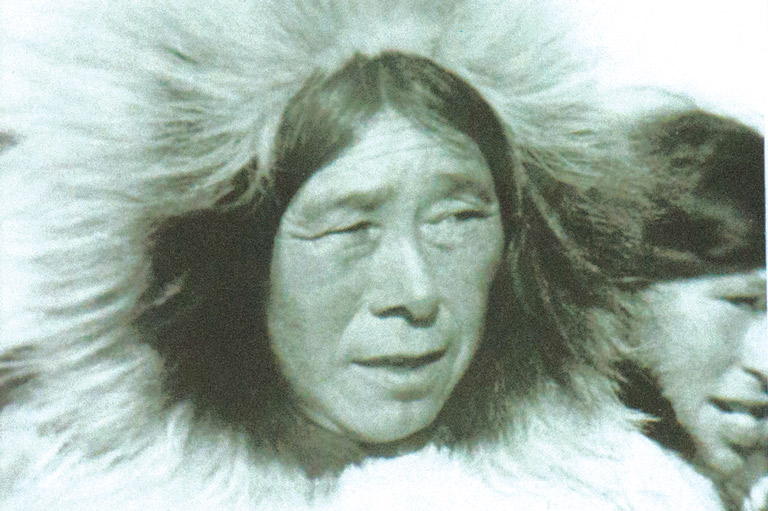

Dahwana, Mary Carpenter's paternal grandmother, date unknown.Courtesy of Mary Carpenter

Dahwana, Mary Carpenter's paternal grandmother, date unknown.Courtesy of Mary Carpenter -

Fred Carpenter's schooner, the North Star of Herschel Island.Courtesy of Mary Carpenter

Fred Carpenter's schooner, the North Star of Herschel Island.Courtesy of Mary Carpenter -

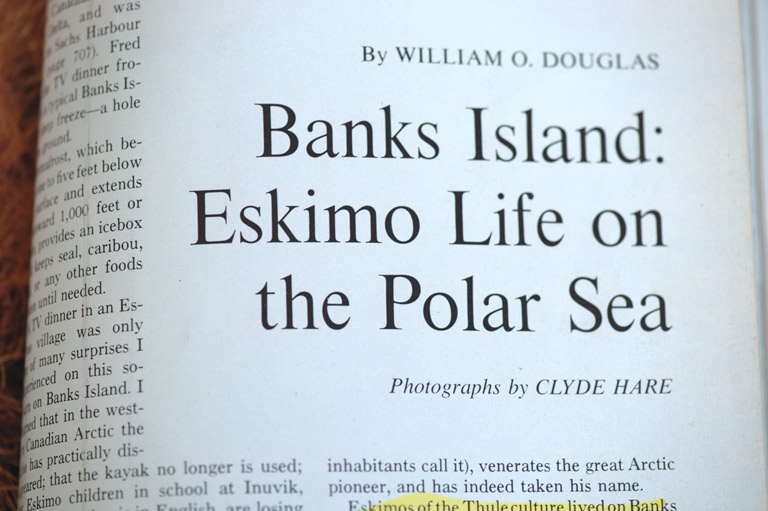

A 1964 National Geographic article featuring the Carpenter family.Courtesy of Mary Carpenter

A 1964 National Geographic article featuring the Carpenter family.Courtesy of Mary Carpenter -

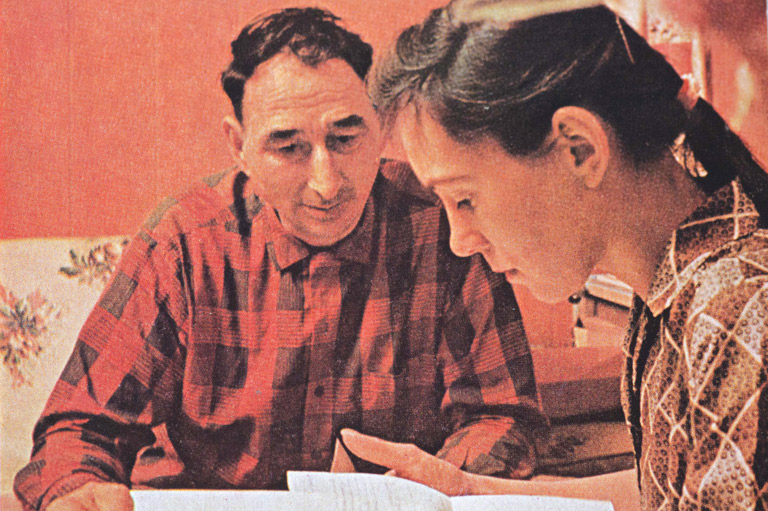

Mary Carpenter and her father Fred in 1964.Courtesy of Mary Carpenter

Mary Carpenter and her father Fred in 1964.Courtesy of Mary Carpenter -

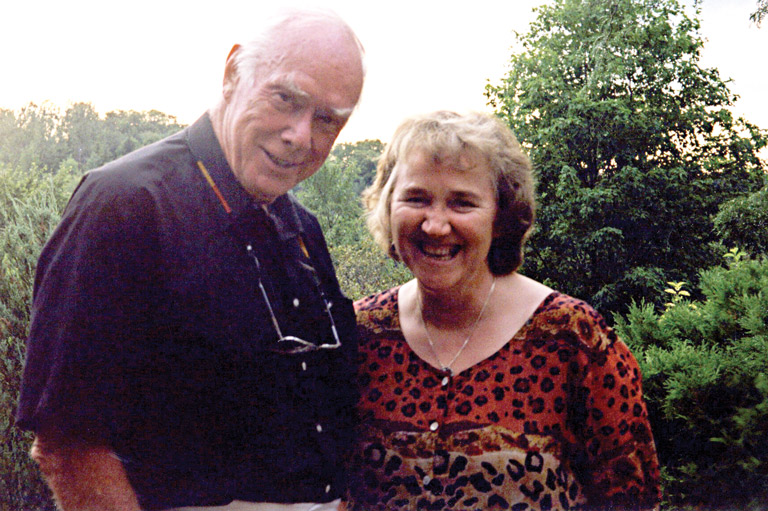

Carpenter with author Pierre Berton, circa 1990s.Courtesy of Mary Carpenter

Carpenter with author Pierre Berton, circa 1990s.Courtesy of Mary Carpenter -

Ada Gruben, Mary Carpenter's mother, in Tuktoyaktuk, Northwest Territories, circa 1930s. Gruben died in 1956 at age 38.Courtesy of Mary Carpenter

Ada Gruben, Mary Carpenter's mother, in Tuktoyaktuk, Northwest Territories, circa 1930s. Gruben died in 1956 at age 38.Courtesy of Mary Carpenter -

Mary Carpenter in her home in Ottawa, January 2017.Courtesy of Mary Carpenter

Mary Carpenter in her home in Ottawa, January 2017.Courtesy of Mary Carpenter

In 1966, Mary Carpenter appeared on national television and shattered the myth of residential schools as the “saviours” of Indigenous children. As a guest of The Pierre Berton Show, the twenty-three–year-old Inuk from Sachs Harbour, Northwest Territories, wept as she spoke of the physical and mental abuse she suffered. It was a shock for thousands of viewers, who had for generations been fed a lie: that forced assimilation was the answer to Canada’s “Indian question.”

Today, Carpenter is an award-winning writer and poet. She holds degrees from Rutgers, Western, and Carleton universities. She is a mother and a grandmother. She is also a residential school survivor. This is her story.

In 1939, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled, unilaterally, that Eskimos — today known as Inuit — were “Indians,” and as Indians they were wards of the Crown. The Canadian government authorized various religious organizations, with aid from the police, to herd Eskimo children into residential schools — as they had been doing to Indian children in southern Canada.

Eskimo children were taken away by airplane from their parents and clan groups, and all familial ties were severed. That is what happened to me. At a very young age, I, being an Eskimo child, became one of these residential school inhabitants.

Before contact with southerners, I had lived my life as the cherished daughter of a wealthy, cosmopolitan father who was the acknowledged leader of two strong Inuvialuit clans. We did not need Canada or its schools and hospitals to survive. We were an entity unto ourselves. The quality of my life with my clan was exceptionally high. Contact with colonial Canada diminished my life and uprooted my clan. We are still struggling to recover.

Officially, the primary purpose of residential school was to Europeanize Indigenous peoples and to uproot us from our former “inferior” cultures. The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples has described these schools as “internment camps for Indian children.” We, as interns, experienced mechanisms of control. I, as well as others, believe that residential schools, run as institutions, prepared us better for jail than for life in white society.

I entered the residential school system in 1948, when my father reluctantly handed me over to the missionaries at the Immaculate Conception Roman Catholic Missionary School in Aklavik, Northwest Territories. Until that moment, I had never seen a white woman, or a two-storey building. The school smelled of strange chemicals that I would come to learn were kept under the kitchen sink for cleaning.

I witnessed with trepidation the transition of parental power when my beloved father handed me over to the Grey Nuns and Oblate fathers. When my father left and the door closed behind him, these alien creatures usurped my Inuvialuit life. I was to stay at the school for one year, before being transferred with my three siblings — Margaret, Noah, and Joey — to the All Saints Anglican Missionary School, also in Aklavik.

At school we found ourselves isolated, not only from our family and homelands but also from our friends and siblings. This isolation made us more vulnerable to the massive brainwashing inflicted on us in order to replace our “pagan superstitions” with Christianity. Relentless labour and routine replaced our former free and easy life.

The nuns harshly punished any expressions of individuality or Aboriginal culture. As we entered the school, the nuns shaved off our traditional long hair and assigned each of us a number. Mine was W3-244. The nuns took away my Native name, Tungoyuq, and replaced it with “Mary,” a name from their Bible. If I dared to utter one word of my Native language, Inuvialuktun, the nuns severely punished me. One of the punishments was standing on one leg in the hallway for all to see with a bar of soap in one’s mouth.

My induction into residential school alienated me from my former life and my identity: what I came to know, who I came to love, what was important to me as a human being. This experience took away my world.

The only contact I had with my father came once a year, and only for two days duration. Each summer, my father would arrive at Aklavik aboard his fabled schooner, North Star of Herschel Island, to trade his yearly catch of white fox furs. I cherished those two days spent with my family, but the women of my clan seemed alarmed at my behaviour because I had become a “bedwetter” and a “clinger.” I was so starved for attention. And when my father’s trading was finished, his departure was heart-rending.

When I finally returned home to Sachs Harbour for good, I was fourteen years old and filled with so much sadness and anger. By this time I was writing seething poetry that alarmed my family. My behaviour, fuelled by resentment and anger, confused them.

Why did my hunter father consent to my incarceration? I needed to know. And so, within hearing distance of my entire clan, I confronted my father with these calculated words: “You are a polar bear hunter, and you know the mother bear either kills or is killed defending her cubs. Why didn’t you do that for me!?”

My father never answered — and my clan never forgave me for these harsh words. They echo back and fuel the despair.

Residential schools shared many similarities with prisons. We were like inmates, our days ruled by routine. Every morning, the bells rang throughout the dormitories, and we lined up for the bathroom, then put on our uniforms, and sleepily and silently walked in a straight line to the cavernous chapel. The Oblate priests, dressed in black robes, chanted from elevated altars and served wine and wafers only to those confirmed into the Roman Catholic Church. The nuns were there to serve the priests and to keep their young charges in line. It was a regimented environment where we soon learned to line up for everything in our daily lives. The white people had all the power. Many children never saw their parents or homelands again.

Residential school became our cultural landscape. Inexorably, we lost our cultural roots. We did not become white, but we were no longer brown. We became lost generations.

Residential schools were driven by a policy that voiced an agenda to “kill the Indian” and “save the man.” The cultural and political extinction of Aboriginal peoples as self-determining nations was integrated as an objective of a school system that was still in place decades after the development of the welfare state.

The volume and intensity of Native testimony about the cultural oppression that characterized the schools make it clear that the official agenda of attempted assimilation was a cause of severe pain and lasting damage.

The layout of the residential schools tells us much about how the white masters controlled the children. Everything about residential school was about severance and barriers. We Inuit children came from a place with no walls, where life unfolded in front of us without any physical or emotional barriers. Therefore, the layout of the residential school and the personnel who administered them were fundamental to reshaping our understanding of space and the purpose of that space.

In my Inuvialuk world, there were no gender differences in names, and our clan system was inclusive. Everyone co-operated. There were no walls, and we all slept and ate in the same space. As children, we learned to live and to thrive in a sensory world. We learned with our five senses. By contrast, the physical space of the school had many walls. We had a defined space to sleep, to eat, to play. We sat rigidly at a desk, facing the teacher. We sat in long wooden pews watching and listening to priests and nuns as they instructed us from a strange, big, black book with a gold-embossed “BIBLE” emblazoned on the cover. In residential school, the Bible was often used to justify the ill treatment of innocent children.

As the weeks turned into months and then years, we learned to line up in order to eat, and to march to class, to chapel, to the dormitory. We learned to respond to and listen for the bells, which dictated our lives. We learned to survive in a regimented world. We learned to bury our senses. Quickly we learned automatic, perfunctory motions such as making the sign of the cross over our bodies, to stand erect like motionless, lifeless, ceramic statues, and to sit erect, like tree stumps, on hard pews. We learned to survive in a world of no laughter and no sound except barking commandments.

At school, the nuns taught us to despise the traditions and accomplishments of our people, to reject the values and spirituality that had always given meaning to the lives of our people, to distrust the knowledge and the ways of life of our families and kin. When the school released us and we returned to our villages, many of us had grown to despise ourselves. We all became damaged goods.

There is no remedy for the severed ties from mother, father, grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins. There will be no “overcome” for me. But writing stories, articles, and poems has given me courage to face my fears, despite being afraid of what I may recall. And I am buoyed by the other Inuvialuit authors who have explored the dark legacy of residential schools.

Magic Weapons: Aboriginal Writers Remaking Community after Residential School, by Queen’s University Indigenous literature scholar Sam McKegney, introduces readers to the writings of several Inuvialuit authors, including Anthony Apakark Thrasher and Alice French. Apakark wrote Skid Row Eskimo in the early 1970s while incarcerated in Calgary. When one considers the theft of land, dispossession, and discriminatory legislation that have historically defined Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal relations, one wonders who the true criminals are and what true justice is.

Alice French’s story My Name is Masak was published in 1977 and focuses on her Inuvialuk name. In her book, she signals to the world that she is reclaiming her identity as an Inuvialuk woman despite her years in residential school and the enforced familial disconnection.

Stories such as those written by Apakark and Masak are the sparks that will ignite the formation of Inuit circumpolar identity and imagination. My Inuvialuit ancestors were imaginative people! This writing will also expose the capacity for Indigenous strength in light of Euro-Canadian assumptions about our supposedly inherent weakness.

Many residential school survivors have died without forgiving their parents, the government, or the churches. They died thinking that it was impossible to escape the terrible heritage imposed on their lives. Our common tendency was, as legal “wards of the Crown,” to self-destruct from inherited paranoia and inefficiency. The educators drilled into me that white people came to the North American continent solely from their sense of duty to their God. They told us we should be grateful for their forced assimilation.

None of my ancestors invited them. I owe them nothing.

Being a residential school survivor, I understand how political manipulation works. I had fourteen years of incarcerated lessons on genocide! Taima! (Enough!).

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

Awakening to womanhood

I remember when I was a young girl

And I was at the Yellowknife airport

I noticed a man and a woman

Who seemed very much in love?

But they were not wrapped

up in each other

with their eyes

or their bodies

I could just observe

That they were different

They desired each other

It was intoxicating

“Don’t stare so, it’s rude!”

That was the Akaitcho Hall supervisor

I stated that those two

Sure looked ripe

She smiled and informed me

They had only met a few days ago

and their marriage was

the talk of the town

As Supervisor was distracted

I slowly eased closer

to get a better look?

I somehow thought

They were wonderful

He had a refined voice

I thought the woman lucky

Someone mentioned she taught skating

I blushed and startled

As I met the sky-blue eyes

Which seemed amused by my

Youthful curiosity

I straightened as tall as Juneau

While he sat

And I told him with my mind

That one day I would be a poet

And men would fall with desire at my feet

And that there would be no blue skies for me

Only golden men with eyes

The color of earth…

— Mary Carpenter, 1967

Northwest Territories

O arched northland of tensed wonders

Your ice-eyed beauty

Captures the strong hearted

With the privilege

of nesting in your hearth

O tender land, uniquely north

Your fate is much discussed

By distant men who sit

And watch your primal lovers

slowly dying…

Who sit and build

Invisible, governing walls

Suborning your chosen without consent

You hum disgust

But your crowning skies forgive

granting oppressors safe journey south

O might land strike now

Show your true heart

bear fruit again and mother us

Granny capital* has heard your pleas

From men who sincerely dishonour you

Deceiving your innocent fire-watchers

How long will you allow it?

the tenders despair…

O great-land, you are leached by white lies

lip-serviced, not loved!

*Ottawa

Mary Carpenter

Tuktoyaktuk, NT. 1967.