Travellers through Empire

A new book records the stories and experiences of some of the many Indigenous people who travelled to Britain and other parts of the world in the late eighteenth century and during the nineteenth century. Their trips were undertaken for various reasons, including missionary work, education, performing, and advocating on behalf of their communities.

On their voyages they were received with curiosity and often as celebrities, sometimes speaking before huge audiences and meeting with royalty and leading figures of the day. But their journeys took place at a time when humanitarian perspectives were mixed with colonial and assimilationist policies.

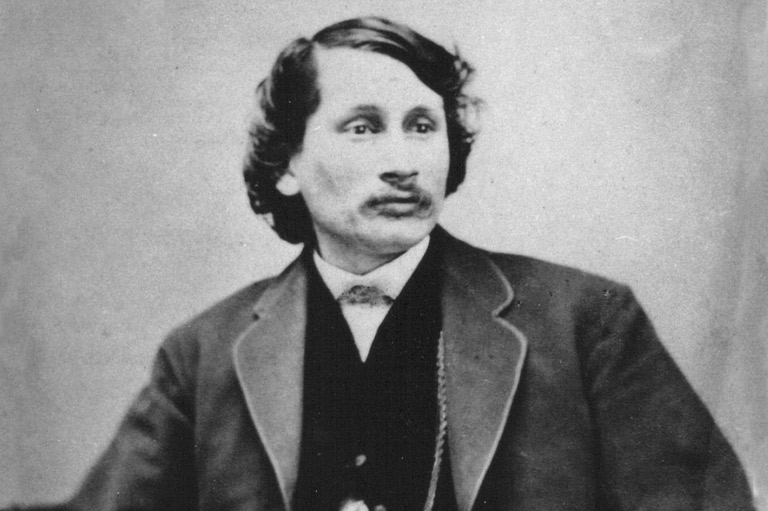

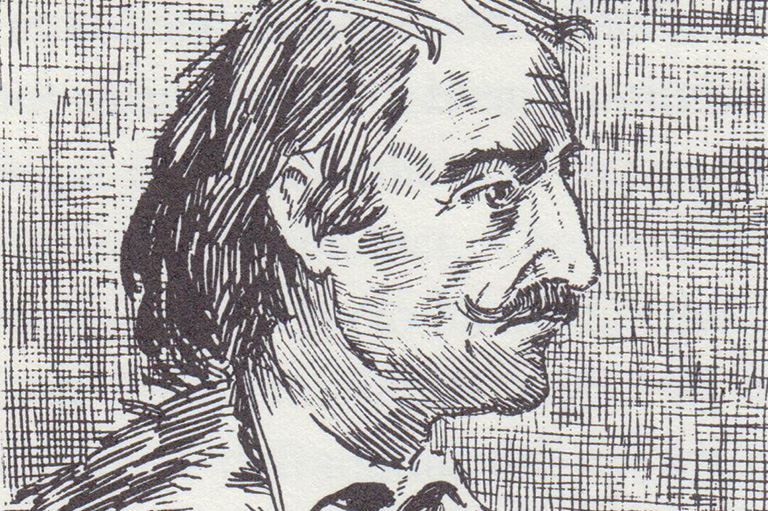

In Cecilia Morgan’s Travellers through Empire: Indigenous Voyages from Early Canada we find people such as Peter Jones (Kahkewaquonaby) and George Copway (Kahgegagabowh), members of the Mississauga people of Upper Canada who were also Methodist missionaries as part of a nineteenth-century global missionary movement.

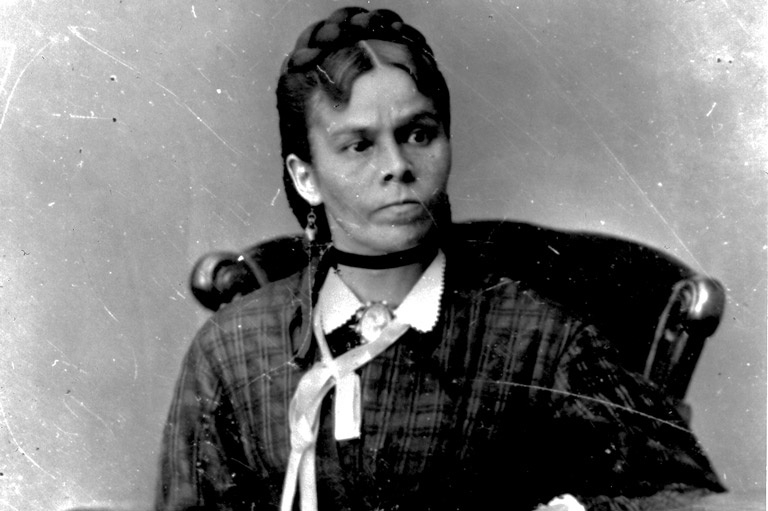

We also read about Jones’ niece Catherine Sutton (Nahneebahweequa). After several moves by her family and other Indigenous people, they were denied access to their lands. Sutton was selected to represent them by travelling to London — where she was received by Queen Victoria — and her family was eventually allowed to buy back their land.

Not only did these travellers lay claim to a more fluid, multi-layered performance of Indigeneity than that of the assimilated convert, they also assessed, commented on, and judged British society, highlighting both its assets and its foibles. While Peter Jones shaped the world of the Ojibwe for a variety of audiences, he also told his Upper Canadian audiences about England, reversing the customary pattern of the period’s travel literature and nascent ethnographies in which the colony was brought to the metropole. “I thought you would be glad to hear my remarks, as an Indian traveller, on the customs and manner of the English people,” he wrote to the Christian Guardian. He found the English generally a “noble, generous minded people — free to act, and free to think — they very much pride themselves in their civil and religious privileges, in their learning, generosity, manufacture, and commerce, and they think that no other nation is equal with them in respect to these things.” Jones found them very “open and friendly … ready to relieve the needs of the poor and needy when properly brought before them.”

He did, though, characterize the English as very fond of “novelties” — no nation, in fact, was as taken with new things. Here, Jones displayed an acute awareness that his appearances in Britain were performances staged and enacted before an audience, part of the theatre of both the missionary and the British colonial worlds. “They will gaze and look upon a foreigner as if he had just dropped down from the moon: and I have often been amused in seeing what a large number of people, a monkey riding upon a dog, will collect in the streets of London where such things may be seen almost everyday.” Jones went on to hint at the tensions he faced. “When my Indian name is announced to attend any public meeting, so great is their curiosity that the place is always sure to be filled; and it would be the same if notice was given that a man with his toes in his mouth would address a congregation in such a place, and on such a day, the place without fail would be filled with English hearers.” Jones’ causes might benefit from the attention paid to him as an “Indian,” but he was acutely aware that his audience might see him as both a celebrity and an exotic spectacle in a theatre of colonial attractions, one whose novelty might wear off as other, even more exciting, representatives of “otherness” appeared.

While appreciative of the English support for overseas missions and English philanthropy, Jones noted the hold that commercial capitalism had on his hosts. “Their close attention to business, I think, rather carries them too much to a worldly mindedness, and hence many forget to think about their souls and their God … ‘Money, money, get money — get rich and be a gentleman.’ With this sentiment they all fly about in every direction like a swarm of bees in search of that treasure which lies so near their hearts.” … Although he was, perhaps, too polite — or politically savvy — to mention it, it’s hard not to imagine that Jones knew there was a clear link between the metropolitan desire for “money, money” and settlers’ desire for his peoples’ traditional lands. …

Article continues below...

Their travels also provided them with the opportunity to do more than offer a critical ethnography of metropolitan society. Imperial travel might also provide wider audiences for subtle — and not-so-subtle — attacks on the wrongdoing of settler colonialism. Such attacks were common in the writings of Indigenous travellers. For Catherine Sutton, her entire trip was aimed at righting the wrongs settler officials had committed against her people, a strategy that involved deploying a range of stances and tropes. On the one hand, she frequently depicted herself as possessing a transparent persona, fixed, centred, and not contingent upon its context, telling her “American Friends” that they would be welcomed “at my humble forest home” and promising them they “will find Nahneebahweequa at New York and London to be Nahneebahweequa at Owen Sound.” However, Sutton’s creation of a public identity within the transatlantic world may have been a somewhat more complex process. In many of her public letters and addresses to the Quakers and to periodicals such as the Colonial Intelligencer; or Aborigines’ Friend, she alternated between the use of what may have been, according to some ethnohistorians, the Ojibwe “language of pity” (her constant use of the phrase “poor Indian”), appeals to Christian sentiment, and clear denunciations of colonial injustices. In a fairly typical letter to the “Friends of New York,” published in the Friends’ Intelligencer in 1861, “Nahneebahweequa” blesses them for taking in “an unprotected Indian woman, a lonely, solitary wanderer, a foreign pilgrim in a strange land … all of you did something in this great effort that was made by my poor, despised, downtrodden people.” …

While it may have been politically strategic, as well as integral to her Christian beliefs, for Sutton to perform as a supplicant who appealed to her audiences’ sympathies and sensibilities, hers was not a message delivered only in that idiom. Rather than accepting a subservient place in a colonial hierarchy skewed by distortions of gender and race, she pointed to the ways that Indigenous women in particular suffered from such deformations of the law. “All in a land where the poor slave can come and be a man and a citizen; while the poor Indian woman that is married to a white man can be driven from her home and taken for a white woman; but, when she offers to buy her own land, she is an Indian.” Nevertheless, despite the Indian Department’s imposed categories, she wrote, “I am an Indian; the blood of my forefathers runs in my veins, and I am not ashamed to own it; for my people were a noble race before the pale faces came to possess their lands and homes.” Yet despite having been well received by the Duke of Newcastle and the Queen, the duke had betrayed her. He had pretended that the Indian Department was innocent of any charges of wrongdoing. Instead, ignoring Sutton’s male fellow petitioners, Newcastle claimed that her marriage had turned her into an Englishwoman and that she had no claim to her lands. Nahneebahweequa disputed these charges, pointing out that she had been married since 1839 and only now been told of her changed status; she also argued that the numerous other Indigenous women who were married to non-Indigenous men had not suffered such discrimination. …

Far from being helpless, Sutton herself had been wronged and was determined to right that fact. Overseas travel, then, might mean the chance to defend rights to land and to call attention to the betrayals of colonial administrations, as well as giving Christian Indigenous people a platform from which they could demand humanitarian support and sympathy from their audiences. Emotional bonds might lead not to mourning but to political activism. ...

The International networks that brought these travellers to Britain also brought them into the orbit of prominent and well-known figures within British society, figures whose patronage helped shape their movements within metropolitan centres. A range of politicians, religious leaders, and prominent philanthropists — Daniel O’Connell, the politician John Bright, and the Queen’s cousin and leader in the Aborigines’ Protection Association, Sir Augustus d’Este — met with them. These meetings were publicized and promoted as proof of their visibility and the potential of increased assistance that they might receive from such contacts. In particular, an audience with Queen Victoria was a significant moment in their metropolitan tours. Eliza Jones noted that, on July 18, 1837, she began to help her husband prepare for his interview, which took place almost two months later, on September 14. To be sure, her description of the audience does not suggest a great deal of pomp or spectacle, except for Jones’ Indigenous dress, worn on the advice of his patrons. “When the folding doors were thrown open, we saw the Queen standing about the middle of the room, each advanced bowing several times till at last they met, when Peter went down on his knee holding up his right arm, on which the Queen placed her hand, he then rose and presenting the Petition said, he was much pleased to be introduced to Her Majesty, explained the nature of the petition and the wampum chain.” Victoria smiled and “appeared pleased to hear that the prayer of the petition had been granted.” Jones then told her that he thought she might like to keep the petition “as a curiosity,” which she accepted and, having asked about his visits to England, “she bowed to indicate the visit was over, he did the same, they then receded backwards, at length the little Queen turned her back, and the interview was over.”

Far from being helpless, Catherine Sutton had been wronged and was determined to right that fact.

A royal audience added a degree of lustre and prestige to the status of a colonial subject. Moreover, their position as a celebrated representative of their people also could be underscored by links to historical Indigenous individuals who had been attributed a semi-monarchical or regal status. Jones stated that he was part of a long line of Indigenous people, such as Pocahontas and King Philip, both of whom had enjoyed an elevated position within their own nations and had also been highly visible actors within metropolitan and colonial society. George Copway’s connections with particular members of English society, many of them committed to liberalism and reform causes (abolition and penal and educational reform, to name a few), are interwoven throughout his book Running Sketches, offered as proof that he was recognized as an important figure. While in Liverpool, he was entertained by Richard Rathbone and his brother, the former mayor of that city, along with the “chief magistrate” E. Rushton, who had previously accompanied Copway to watch Police Court proceedings. In London he actively sought out a number of English politicians. Copway dined at Fintan’s Hotel with Mr Brotherton, “the vegetarian MP”; breakfasted with Richard Cobden, whose “solid English look I very much admire” and who asked him a number of questions about his country and people; and went to dinner at Lord Brougham’s, where he met lords and a marquis, “a nobler set of Englishmen I never beheld.” The company also included Mr. Gambardilli, the “celebrated portrait painter.”

After leaving his lodgings from Randall’s Hotel in Cheapside in favour of Hanover Square’s much quieter (and likely more elite) George Street, Copway found “an abundance of cards on my table. O fie, fie: these English will spoil me.” Gambardilli, Dr. Wiseman (quite likely the Roman Catholic cardinal), E. Saunders the “celebrated dentist,” and Lady Franklin and her brother, Sir Simpkinson: all extended dinner invitations, which he was happy to accept (although he was left exhausted by them). Upon his return to London, Copway feared he would disappoint his many callers. He was running out of time in London and, as well as receiving numerous letters and cards, also had invitations from two committees who wanted him as a speaker.

While it is difficult to determine whether all these meetings took place, the political and social concerns of many of these individuals makes it quite plausible that they would be sympathetic to and curious about the “Ojibway chief” who was so concerned about the well-being and advancement of his people.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Our online store carries a variety of popular gifts for the history lover or Canadiana enthusiast in your life, including silk ties, dress socks, warm mitts and more!