Doughboy Jack & Handel's Messiah

Episode Transcript

Mark: Tell us about the context for this song, and its content.

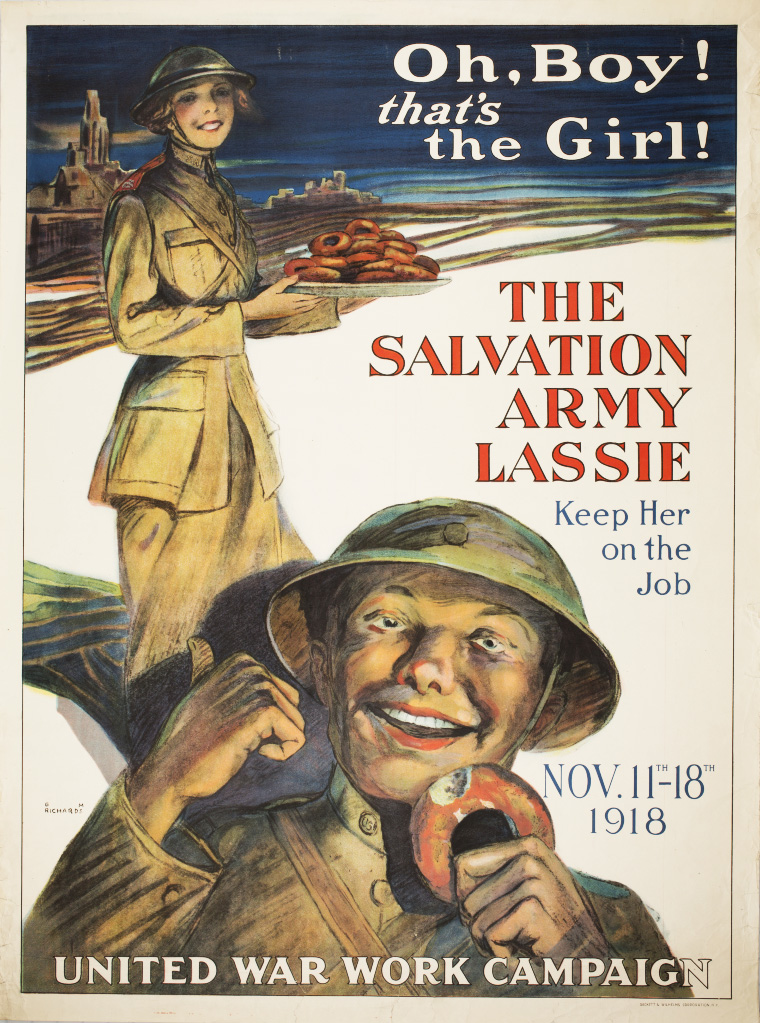

Rachelle: During World War I, the Salvation Army workers served coffee and doughnuts to soldiers in the trenches. Rations were poor so the doughnut idea was conceived as a means of bringing the soldiers cheer. These doughnuts were actually called doughboy donuts. As for the content, it’s the story of a chance encounter between a Salvation Army doughnut cook, Jill, who encounters a soldier, Jack, on the French front. It’s love at first sight for Jill and Jack; their love is so strong that everyone around them comments in the refrain: “Doughnut Jill loves Doughboy Jack /and just as soon as they get back/they’ll steal away on their wedding day/ to the little house that Jack has built for Jill/I say they will. So it’s a humorous love song from WWI that combines Salvation Army doughnut cooking with the nursery rhymes Jack and Jill and, as you can tell from the lyrics of the refrain, the cumulative English nursery rhyme This is the House that Jack Built. Quite a tour de force! Interestingly, the couplets are sung by O’Hara’s tenor voice to words that are obviously those of a woman, Jill.

Mark: Can you give us some information about the author of this popular humorous WWI song?

Rachelle: The song’s author is a fascinating character: Nova-Scotia born and Montreal-educated Gitz Rice. As a youth, he earned the nickname “Gitz” due to his limping gait, but this didn’t prevent him from enlisting in the army on the exact day Britain declared war on Germany in 1914. He began writing songs during training, mostly poking fun at the training procedures. He also organized the first World War I concert party for servicemen in France! Rice joined Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry Comedy Company as a piano player, and survived the war to become a prominent vaudeville musician. One of his clearest war memories was the time when he saved a piano from destruction, and this surely deserves to be recounted here: “I shall never forget, in one town, stealing a piano out of an old house that was being shelled. The piano would have been destroyed anyhow. We got a wagon, put the piano on the wagon, and drove down a road where thousands of infantry boys were lined along the sides. I couldn’t keep my fingers from the keys, and started to play as we went along. There were shouts, cheers, and singing, and one English soldier came up to me in all seriousness and said: ’What is the idea of the celebration? Has peace been declared?’ Of course, I had to answer the negative.”

Mark: How about the performers, tenor Geoffrey O’Hara and pianist Willie Eckstein?

Rachelle: Both were extremely popular, gifted performers, and also extremely successful. O’Hara hailed from Chatham, Ontario and enjoyed a long and academically successful career in the United States as a songwriter, composer, singer, teacher, lecturer, army singing instructor, ethnomusicologist, pianist and guild organizer. Montreal-born Willie Eckstein, also known as “The Boy Paderewsky” or simply “Mr. Fingers” was, to quote the Library and Archives Canada’s Virtual Gramophone website, so slight in stature that he could not serve in the army, but stood as a giant among Montréal’s popular-music pianists from the very earliest days of ragtime and jazz in Canada (from VG site). He was refused the opportunity to serve in the armed forces because of his height, which was under five feet (around 150 centimeters). Music became Eckstein’s contribution to the war effort; he composed songs such as “Goodbye Soldier Boy” (1917), and performed at war rallies.

Mark: Tell us a bit more about the recording itself.

Rachelle: Here, in short, we have a trio of supremely talented Canadian musicians whose work served the dual purpose of encouraging Canadian troops in the war effort, and enriching the early recording industry with their imaginative and highly popular contributions. For O’Hara and Eckstein this activity continued after the two world wars. The song Doughboy Jack and Doughnut Jill was recorded on the Montreal Berliner Gram-O-Phone company label around 1919. It is a 78 rpm, 10 inch monaural sound disc.

Mark: Any concluding remarks?

Rachelle: The First World War was a time of great international conflict but also the source of a great quantity of popular patriotic songs written by Canadians. In the face of hardship, it is often human nature to respond with humour and levity. A prime example of laughter, hope, and imagination in the midst of despair and adversity is the song Doughboy Jack and Doughnut Jill by Gitz Rice, performed by tenor Geoffrey O’Hara and pianist Willie Eckstein. The song also revives and interesting detail of the war effort, the Salvation Army doughnut campaign. It also references two nursery rhymes that must have been highly popular at the time and evidently, still are. This song can thus be taken as a witness of cultural context and wartime practices combined with a humorous narrative of hope and of better days ahead.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

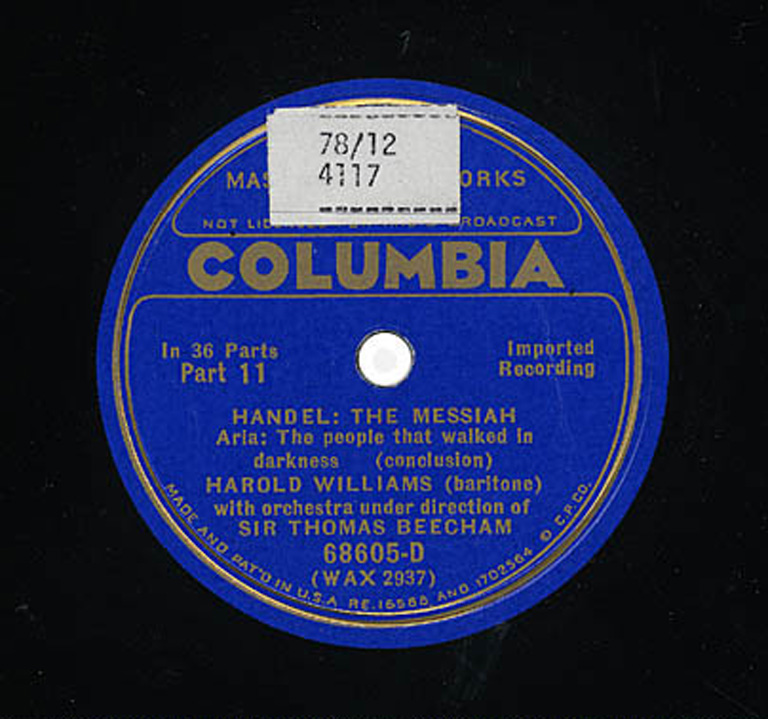

Mark: This is an interesting example of how a monumental work of the baroque era, George Frideric Handel’s Messiah was issued on 36 separate 78 rpm 12 inch discs, of which this aria is the 11th. Can you tell us more?

Rachelle: Yes, well that, and many other things about this recording are very interesting. The concluding section of this number from Handel’s Messiah (written in 1741) is part of a historic performance of the full oratorio by the BBC Symphony Orchestra and BBC Symphony Chorus conducted by Thomas Beecham. It was made in 1927 — during the period between the two great wars — but has enjoyed an astounding longevity and is still being reissued today. It crops up on everything from formal reissues on established record labels to other supports, such as Spotify or iTunes. Evidently, it was a gigantic hit and the fact that it endures to this day is a tribute to its artistic merits, especially in this day and age of historically-reconstructed performances of baroque music. Of course, today it is available on compact disc and mp3 files and other digital supports, whereas back in the 1920s you probably had to rent a cart and horse to carry the 36 discs home, to listen to Messiah in sections on your gramophone player! Listening to music could be rather an elaborate thing compared to today.

Mark: This excerpt is from a recording made in London, England, performed by a British orchestra and conductor, sung by an Australian baritone, and manufactured by the Columbia Phonograph Company in New York. Is there anything Canadian about it?

Rachelle: There are in fact many relationships between this recording and Canada. The first and most obvious relationship is that another soloist on the Messiah recording is the tenor Hubert Eisdell, who settled in Canada and enjoyed a huge success on the concert stage in both England and Canada. Second, one must understand that the classical music scene, and especially the scene involving opera and oratorio singers, was a global phenomenon. At the centre of classical music performance was Sir Thomas Beecham (of the powerful Beecham Pharmaceutical Company family) and Beecham was a great champion of Canadian-born singers, who in turn definitely made their mark on European classical music. Great Canadian singers Kathleen Ferrier, Lois Marshall, Pierrette Alarie, Raoul Jobin, Jon Vickers, and many others owe much to him. It is no wonder that Library and Archives Canada would have acquired this primary source as it must have been purchased by many Canadians who had a taste for this repertoire and the means to buy the set. This was an exceedingly popular performance of a hugely popular work. And Messiah is, of course, still an essential part of Canadians’ classical music experience.

Mark: Anything more to add about the performer, Harold Williams?

Rachelle: Like many gifted singers, both classical and popular in this period, Harold Williams’ singing talent was brought to public notice – perhaps paradoxically so – through the First World War effort. When Willilams sailed in the Argyllshire in May 1916 as a corporal in the 9th Field ambulance, he also entertained mates with vigorous ballads. He saw action in France and Belgium and along the way was transferred, no doubt because of his talent and charisma, to the Australian army entertainment unit, “Anzac Coves”. On leave in England in 1918, Williams sang at a private party at Sheffield and was noticed by a number of musical luminaries who were keen on encouraging him to embark upon a classical music career. He began formal music studies, entered numerous competitions, and made his début recital at Wigmore Hall, London. The rest is history. He lived until 1972.

Mark: Tell us a bit more about the recording itself.

Rachelle: The excerpt we will hear is take 4, side A of disc 11 in a 78 rpm, 12-set of 36 discs recording the complete Messiah by Handel and totalling 2 hours of play. The set was manufactured in October 1927 by the Columbia Phonograph Company of New York, the recording’s primary label. The master version was made on wax cylinder and recorded on July 1st (another Canadian connection!) 1927 in London, England featuring Sir Thomas Beecham conducting the BBC orchestra and choir, with soprano Dora Labbette, alto Muriel Brunskill, tenor Hubert Eisdell, and baritone Harold Williams. The excerpt is from the bass aria of Part 1, Scene 3, number 11 entitled “The People that Walked in Darkness Have Seen a Great light,” sung by Harold Williams.

Mark: Any concluding remarks?

Rachelle: The performance on this excerpt is a fine example of the aesthetic approach to Handel’s masterpiece in the earlier 20th century: the phrasing is seamless, the timbre, smooth and melifluous, the tempo, regular, and the balance between voice and orchestra definitely favouring the voice while showcasing the orchestra in tutti passages. The performance would have been considered as “cutting edge” at the time the recording was released, and given Messiah’s popularity, would have been the subject of much enthusiasm, debate, and interest in many middle to upper class Canadian households during the interwar period.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!