Cold War Score

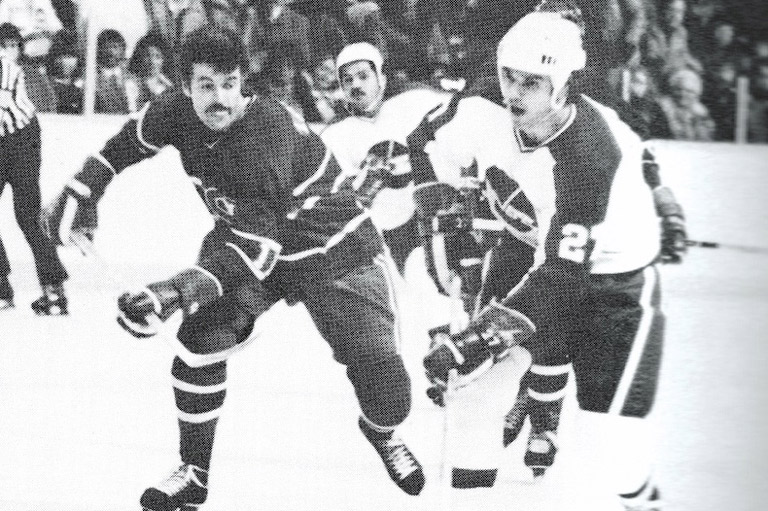

An eight-game series involving professionals from the National Hockey League and the Soviet Union’s “amateurs” started on September 2, 1972, in Montreal. Twenty-seven days later, the teams were in Moscow’s bedraggled Luzhniki Ice Palace — with the series tied at three wins, three losses, and one tie — awaiting the start of a Cold War-on-ice final game.

Team Canada had to win two straight games in Moscow to play the winner-take-all game eight on September 28. Three thousand Canadians travelled to Moscow for the final four games of the series. Millions more watched on television as Paul Henderson scored in the game’s final minute to complete the comeback 6–5 victory.

I don’t know what you were doing when it was all over — or how you felt — but you had to be in the ice palace to truly understand the moment. It was as emotional as it gets.

It was Team Canada players leaving the ice, forefingers pointed skyward, and Canadian fans — so many of them weeping — while breaking into an emotional “O Canada.” It was goaltender Ken Dryden skating frantically down the ice to join the entire team, which had fallen on Henderson in a beautiful tangle of love.

The most frequently used phrase right after this classic comeback was “off the floor.” “We came off the floor,” said assistant coach John Ferguson. The phrase still resonates today.

The Soviets had gone into the third period with a two-goal lead but seemed dazed after Phil Esposito scored his second goal to make it 5–4.

Suddenly there was a scramble in the Soviet goalmouth. In the thirteenth minute, Yvan Cournoyer scored one of the biggest goals of his life — but the red goal light didn’t go on. The referee had his arm raised to signal the goal, but not everybody saw it. Alan Eagleson, the executive director of the National Hockey League Players’ Association, was furious, thinking it would somehow be ruled “no goal.”

Eagleson barged forward from the stands but was stopped by a wall of Soviet police. One officer shoved Eagleson. He shoved back. In an instant, he was grasped firmly by a half dozen police and half-pushed, half-dragged to the closest exit.

Noticing Eagleson’s plight, several Team Canada players scrambled to free Eagleson, pulling him over the boards and onto the ice to escort him to the Canadian bench. It was then that the doors opened at each end of the arena to allow dozens more police to enter, rifles slung over their shoulders. Within a few minutes, the Soviet police stood shoulder-to-shoulder in a tight, menacing ring around the entire group.

There is no way of knowing if this incident had any effect on the players, but I suspect it did. After two periods of struggling to stay alive, after starting the third period down two goals, Team Canada found the inspiration to play as it never had before.

Henderson had scored the winning goals in games six and seven. In the final minute, he found himself in front of the Soviet goalie, Vladislav Tretiak. He shot ... and there was a rebound. He jumped on it and shot again. The light wasn’t on, but the players raised their sticks. Dryden skated down the ice, and the players spilled over the boards. Canadians in the crowd were on their feet, staring at each other in disbelief. Strangers hugged one another among a red sea of Canadian flags.

This Summit Series finale wasn’t the best-played game ever. Emotions “and elbows” were high throughout the match. At one point, Canadian players threw chairs on the ice over a disputed penalty, and Canadians in the crowd rose to their feet, chanting: “Let’s go home! Let’s go home!”

So, what made this victory so special?

At the time, I had been covering major sports events for nearly twenty years. Involvement was something I avoided then and always have since. A team wins, a team loses; hockey is only a game. But, I must admit, I was on my feet with the rest of the Canadians following the Henderson goal. Some of the shrill cries were my own. The Canadians who were there, and those who weren’t, still remember it as the greatest goal ever scored.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement