Suffragist Francis Beynon: Not Just an Historical Footnote

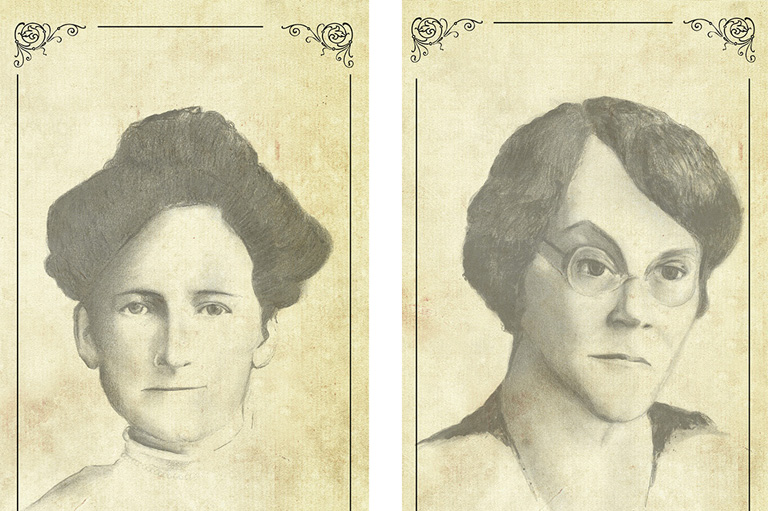

Nellie McClung is perhaps the most famous early 20th-century feminist, and is largely credited with securing Manitoba women with the right to vote in 1916. Numerous books, articles, and memorials have recounted her life and legacy. However, in 2012 I attended a play in Winnipeg (Fighting Days by Wendy Lill) where a lesser-known women’s rights advocate took her rightful place in the spotlight.

Francis Beynon was born in Streetsville, Ontario and grew up on a farm in Manitoba after moving there as a young girl. In 1912, she became the first, full-time female editor of the Grain Growers’ Guide, a popular journal published for Western farmers. The Guide served as a way to connect farmers with each other and the outside world, with readers frequently sharing information and opinions through their letters to the editor.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

It was in the pages of her column “The Country Homemakers,” where Beynon concentrated her fight to advance women’s rights. Amid answering questions about stain removal and child care, Beynon discussed a number of women’s rights and issues — among them education, enfranchisement, equality, and independence. “The Country Homemakers” became a space where women expressed ideas, thoughts, and opinions, and different notions of women’s rights were shared and popularized.

When the Great War broke out in 1914, Beynon began to distinguish herself as a radical feminist. Most suffragists — many of whom had loved ones in the war — were ardent supporters of the war. They were pro-British, nationalistic, and their desire to win the war began to overshadow the women’s cause. They supported conscription as a means to win the war quickly, and were leery of “foreign-born women” (i.e., non-British) who did not share their patriotic zeal.

Beynon, on the other hand, was a pacifist and continued to advocate for women’s suffrage on the basis of equality. She fought for enfranchisement for all women, not just for Canadian or British women, like some of her counterparts. Her radical views were unpopular among many and, in 1917 she resigned from The Guide and moved to New York. There, she joined her sister and brother-in-law who were also forced to leave Winnipeg because of their pacifism.

Despite being front and centre of the suffrage movement, Francis Beynon drifted into obscurity and has been largely omitted from the historical record. As the director of Fighting Days wrote in the program notes, she became “a mere historical footnote.”

If you believe that stories of women’s history should be more widely known, help us do more.

Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share women’s stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement