Savouring Stillness

Gregorian chants fill the church at the Abbey of Saint-Benoit-du-Lac, 150 kilometres southeast of Montreal. More than a dozen Benedictine monks face one another in the choir stalls — some in black habits, others in white, a few with jewel-toned stoles marking the ordained. It’s 11 a.m., eucharist, the day’s high point, and the prayer is monophonic Latin plainsong — the centuries-old voice of Roman Catholic worship. A cantor begins; a small choir replies. The sound rises and falls in slow, gentle swells and feels spare yet intimate, like a shared heartbeat. This is prayer as the small community has known it for generations — steady enough to carry them from their 1912 founding to this morning’s mass, where anyone, believer or not, can slip into a gallery seat, listen and feel the room go still.

I’m here with my husband and our two daughters, nine and 11. We hadn’t planned on the chanting; we came for the cheese. Our family has travelled to Quebec’s Eastern Townships to sample the region’s 14-stop fromagerie circuit, and our elder daughter is set on visiting the province’s last cheese-making monks — the makers of her favourite Swiss-style Frere Jacques.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

But once we arrive, it’s clear that cheese is only a small slice of the story. Beyond the award-winning fromagerie is a living monastery whose roots stretch from St. Benedict in the fifth century through post-Revolution France to a modern architectural landmark. Our visit also gives us something unexpected: a moment of calm in an otherwise-packed family itinerary.

My picture of monastic life is fuzzy and imported — more Buddhist than Benedictine. Our guide, the abbey’s communications coordinator David Morel, says that’s common. We start with the basics: who St. Benedict was (an Italian monk from Norcia who lived from CE 480 to CE 547), what a day at the abbey actually looks like, the architecture and the businesses that keep it running.

Exile and tragedy

The story goes back to exiled monks from the abbey of Saint-Wandrille in Normandy in 1901. Driven out by the French Republic’s anti-religion laws, they found temporary refuge in Belgium before settling in Quebec to live the Rule of St. Benedict — prayer, work, life in community — in peace. With the blessing of the bishop in Sherbrooke, Dom Paul Vannier bought land and an old farmhouse on the west shore of Lake Memphremagog in 1912. The start was shaky. Though five more French monks arrived just before the First World War, in the fall of 1914, a motorboat that Vannier was travelling in with Brother Charles Collot struck ice and sank in the lake; both men were drowned. The war cut the community off from its founding abbey; money and labour were thin, and closure was on the table — until Canadian postulants stepped forward and the monastery was saved.

Modern landmark

Saint-Benoit-du-Lac isn’t Canada’s oldest monastery, but it’s one of Quebec’s best known — thanks to the Benedictine name, the setting on Lake Memphremagog and architecture that keeps drawing journalists, filmmakers and day-trippers alike. By the mid-1930s, the community had outgrown the farmhouse; in 1935, it became an autonomous monastic community, and in 1939, Quebec recognized it as its own tiny municipality — a hamlet of monks on the lakeshore.

They turned to Dom Paul Bellot, a French monk and architect celebrated for his parabolic arches and polychrome brickwork. By 1941, two stone wings were up — including the much-photographed corridor of geometric-patterned floors, brick ribs and natural light. From the 1940s to the ’60s, Dom Claude-Marie Cote, inspired by Bellot, added the chapel, guest wing, crypt and tall bell tower. In 1952, the monastery became an abbey with 60 monks, led by Very Rev. Dom Odule Sylvain.

The monastery’s contemporary era arrived with the design of the new church, completed in 1994, by Romanian-Canadian architect Dan Hanganu. Outside, a smaller bell tower connects to the old one by a slim bridge on the granite facade. Inside, metal columns extending from the original masonry arches frame a paredback space where daylight spills in a vertical shaft into the sanctuary. The raised altar sits before a wall cut with tall, narrow slits that filter blue sky, and from one special spot in the church, a glimpse toward Lake Memphremagog and Owl’s Head Mountain.

Advertisement

Self-sustaining life

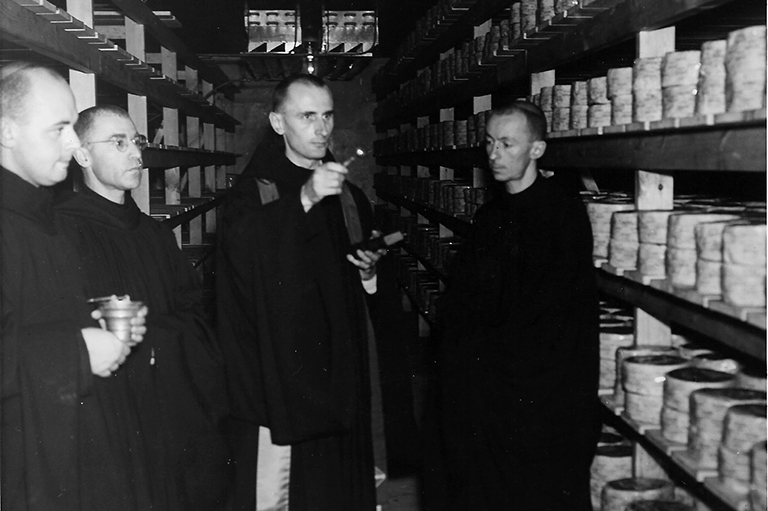

“Pray and work” is Benedictine shorthand for a balanced day — and their “work” happens to be delicious. The monks began making cheese in 1943, producing Quebec’s first blue, Ermite; a biochemistry-trained brother later helped expand the lineup, which today includes a dozen varieties.

Among the cheese-factory founders was Brother Anselme Gravelle, who passed away in late 2025 at age 103. Until late in his life, he attended daily prayers and did light chores. On his 100th birthday, Gravelle recalled wanting to be a priest after elementary school but realizing he wasn’t suited for it. Instead, he turned to the abbey — and never left. Despite being, in his own words, “afraid of animals,” he worked in the dairy and on the farm, laying the foundation for an enduring cheese-making tradition. Saint-Benoit-du-Lac is the oldest running fromagerie in Quebec.

Today, 24 monks oversee a modern fromagerie run by lay workers. The output has climbed from thousands of kilos in the 1940s to hundreds of thousands. “It takes patience and dedication,” says Morel. “You can’t enjoy it right away. It’s a labour of love.” Thousands of apple trees help round out the monks’ livelihood with ciders, compotes and preserves and fall apple-picking open to the public.

We finish where most visits end: the shop, its shelves packed with the monks’ handiwork, including those award-winning cheeses. We leave the shop with our arms full of wedges. One slips off our elder daughter’s pile and thumps to the ground. A passing monk pauses, grins and — breaking his own silence for a beat — says, “Don’t toss that. It’s still good.” A small joke, and a fitting reminder that even a life of devotion leaves room for a little indulgence.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

IF YOU GO

EXPLORE: Tucked between Appalachian foothills and the Vermont, Maine and New Hampshire borders, Quebec’s Eastern Townships have welcomed travellers since 1850, with alpine charm, history and local flavour in every direction.

PLAY: In Sutton, hike Mont Sutton or ride Canada’s steepest zipline, then unwind on Magog’s Marais boardwalk amid wetlands and birdsong.

EAT: Cycle the 235-kilometre Véloroute Gourmande past cider mills and vineyards, and don’t miss Compton’s prizewinning Fromagerie La StationorGranby’s Michelin-recommended spot.

STAY: Rest at the luxury Manoir Hovey or Ripplecove Hôtel & Spa on Lake Massawippi, or find rustic serenity at Huttopia Sutton. If you prefer, the abbey’s guest house provides a taste of monastic peace.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement