Victoria's Johnson Street Bridge

The Johnson Street Bridge in Victoria, British Columbia is one of the city’s iconic landmarks. In 2010, after years of debate, the City of Victoria chose to replace the bridge, and a new structure is projected to open at the site before the end of 2018.

While many Victorians lament the passing of the cherished “Blue Bridge,” they seldom remember the earlier bridges that crossed the harbour at the same location. The first bridge was a low-level wagon bridge built 1854–55 and dismantled in 1862.

Reflecting on the short history of the first Johnson Street Bridge draws attention to other overlooked parts of Victoria’s history: the Old Songhees Reserve in Victoria West, racial curfews, and policies of segregation enacted to remove Indigenous peoples from the city limits.

With a fourth bridge at the site currently under construction amidst much debate, now is an apt time to remember the controversy that attended the first Johnson Street crossing.

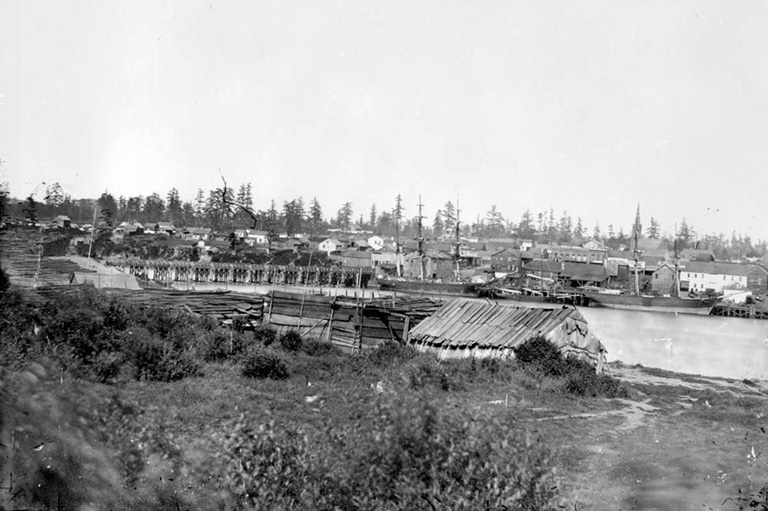

To understand what it meant to bridge the harbour in 1854, one has to understand what lay on either side the structure. In 1843, the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) established Fort Victoria in the historic territory of the Lekwungen people. On the opposite side of the harbour was a village inhabited by the Lekwungen-speaking Songhees people.

In 1850, representatives of the Songhees signed a treaty with HBC Chief Factor James Douglas which guaranteed that their village sites and enclosed fields “be kept for our own use, for the use of our children, and for those that may follow after us.”

The terms of that treaty resulted in the establishment of the forty-eight hectare Songhees Reserve across from Fort Victoria in what is now Victoria West.

In 1854, the first crossing over the harbour was built at the present site of the Johnson Street Bridge. Known as the Victoria Bridge, the crossing helped to connect Fort Victoria to the farms and British naval operations located around nearby Esquimalt Harbour.

It also bridged two relatively distinct cultural spaces—that of the HBC traders in Fort Victoria, and that of the Lekwungen people on the Songhees Reserve.

Victoria expanded dramatically in the wake of the 1858 Fraser River Gold Rush, and newly arrived European settlers brought with them racially charged ideas about what a “civilized” city should look like.

Soon prominent Victorians began to call for the removal of Indigenous peoples from the city and the adjacent reserve. In the spring of 1860, an article in the British Colonist reported a posse of policemen pulling down the last of the “Indian tents and shanties” in the northern section of the city (between Bastion Square and Johnson Street), forcing families to flee across the harbour to the Songhees Reserve.

Historian Renisa Mawani suggests that the Victoria Bridge enabled local authorities to divide the city by racial and spatial differences. A racial curfew was established in 1861, and police received orders to forcibly drive all Indigenous people across the bridge each evening.

Any Indigenous person found in the city after 10 p.m. could be searched and detained. Other segregationist policies were enacted that specifically targeted women. In 1862, the city council enacted a bylaw declaring it illegal to harbour Indigenous women within the city limits, unless they were married or employed by a resident.

The councillor that proposed the bylaw argued that all Indigenous women “might be considered prostitutes and that was sufficient grounds for ejection.” While the Johnson Street crossing connected two cultural spaces, it also allowed local authorities to impose racial segregation between them.

Like those residing within or near the city, Indigenous people on the Songhees Reserve became associated with sexual immorality, disease, and uncleanliness in the minds of white settlers.

In 1859, Councillor Joseph Pemberton asked that the Legislative Assembly either relocate the reserve or remove the bridge and “thus at once isolate the Indians.” Calls for the bridge’s removal continued into 1860s. Beyond linking Victoria to the Songhees Reserve, the bridge was in a rapidly deteriorating condition, and it prevented marine traffic from entering the upper harbour.

Those advocating for the bridge’s removal frequently suggested that harbour improvements be paid for through the sale of the Songhees Reserve. Finally, in May 1862, the Daily Colonist reported that “the last pile that formed a portion of the Old Bridge… was drawn yesterday, and nothing now remains to mark the spot.”

The “Old Bridge” was a focal point for debates charged by racist attitudes and colonial anxieties. It connected Victoria to the Songhees Reserve, but also helped settlers to draw a racial boundary between themselves and their Indigenous neighbours.

While the structure continues to undergo change, the Johnson Street crossing provides an excellent vantage point for thinking through a critical, if largely forgotten, part of Victoria’s past.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement