Hope and Heartbreak

For the sheer density of history that is packed in to a relatively small area, it’s hard to beat Newfoundland and Labrador’s gloriously rugged Bonavista Peninsula, where a drive of perhaps twenty-five kilometres transports visitors through centuries of events and stories that deserve to be much better known by the rest of Canada.

Case in point: Port Union, North America’s only purpose-built union town, which was founded by Sir William Ford Coaker and now includes a National Historic Site. Coaker is one of those rare people who deserves the title of visionary, and yet I’ll come clean: I’d never heard of him before this trip.

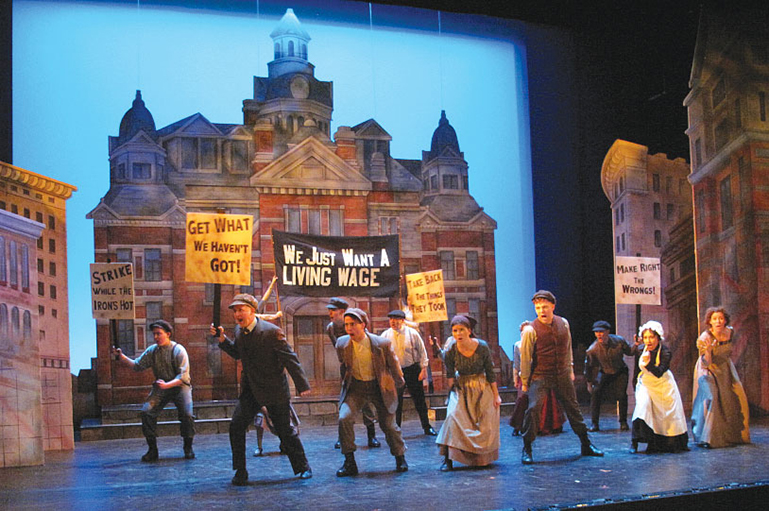

While working at various jobs that took him around the island, Coaker saw struggling, isolated fishermen at the mercy of wealthy merchants. He formed the Fishermen’s Protective Union in 1908 with nineteen members; by 1914 it represented twenty-one thousand members — about half of the fishermen in what was then still the British colony.

Built between 1916 and 1921, Port Union offered fair prices for fish and affordable housing for workers at the fish plant, not to mention unheard-of amenities such as electricity, the territory’s first elevators outside St. John’s, night classes at the community school, a movie theatre, a temperance-inspired soft-drink bottling facility, and a resident local nurse. The Fishermen’s Advocate newspaper, essential reading from its founding in 1910 to its demise in the mid-1980s, educated, stirred controversy, and fostered bonds among its far-flung readers.

Local guides, many of whom worked at the fish plant until its closure in 2010, lead tours of the restored factory building, which houses a wide range of items including the Advocate’s presses, back issues of the paper, examples of local products, and Coaker’s own effects.

A self-guided walking tour around the town culminates in a stop at Coaker’s commanding gravesite overlooking the largely quiet harbour. I left the area with a bittersweet sense of a place where life improved for so many but for such a short time.

The ocean air blew away the wistfulness as we continued our drive, thinking we’d make a quick photo stop about twenty minutes up the road in the village of Elliston. But, as with so much of Newfoundland’s story, humour and history ran right up against each other once again.

Sure, at the entrance to the village there’s a big sign declaring Elliston the “Root Cellar Capital of the World,” but just a few kilometres on we discovered a stunning cove with a tragic story to tell, where a huge granite slab lists the names of the 251 men of the Southern Cross and the Newfoundland who died in the 1914 sealing disaster. A haunting statue depicts a father and son from the village clutched in an embrace, awaiting death.

The peaceful location and brilliant sunshine somehow made the memorial scene even more devastating. A short walk away is the John C. Crosbie Sealers Interpretation Centre, which explores a way of life fraught with danger.

Sobered and sombre, we made the short drive on to Bonavista, which takes its name from the Italian O buon vista! (O happy sight!), words supposedly uttered by Giovanni Caboto (a.k.a. John Cabot) when he is said to have landed here in 1497. (The claim is disputed by residents of Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, among others.)

After taking in the famous red-and-white-striped lighthouse and visiting the statue of Cabot perched atop the jagged cliffs — there are no railings in sight, so if you’re from away, like us, and it’s windy, like it always is, do be sensible — there’s a full-sized replica of his ship, the Matthew, to explore in the town.

Not far away lies the Mockbeggar Plantation Provincial Historic Site, restored to its state in 1939, when F. Gordon Bradley, a passionate advocate of Confederation with Canada, lived there. (The name is said to refer to boggy wet soil that is treacherous for those on foot.) After working with Newfoundland Premier Joey Smallwood to negotiate the union with Canada, Bradley became the new province’s first representative in the federal cabinet.

I hope it doesn’t sound too clichéd to say I had “I’se the B’y” running through my head as I wandered around the nearby Ryan Premises National Historic Site — the traditional folk song throws some good-natured shade on the quality of Bonavista cod.

After a visit to the on-site Bonavista Museum, the importance of cod to this community and this province was crystal-clear, if once again imbued with some sadness at what’s been lost with the fishery’s collapse. The group of white clapboard buildings with neat red trim, once a thriving fish-processing site owned by the Ryan merchant family, now offers musical performances and art exhibitions alongside historical interpretation.

After a day spent rambling over one small piece of one peninsula on this vast island, it’s obvious that all that I or any visitor — especially one interested in Newfoundland’s history — can hope to do is to become aware of how much else there is to learn. It would take a lifetime to do justice to this amazing place — which sounds pretty terrific, come to think of it.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement