The Founding of Fort Severn

In the subarctic tundra six kilometres from the shores of Hudson Bay stands the Mushkego Cree village of Fort Severn, Ontario’s most northern community and one of its oldest continuously occupied settlements. Established before the 1763 Treaty of Paris, which transferred the French colony of New France to the British Crown, it is one of only a small handful of such early communities that remain in Ontario. The others include Kingston, established in 1673 as the French Fort Cataraqui; Moose Factory and Fort Albany, established as Hudson’s Bay Company posts in 1673 and 1679 respectively; and Windsor, which began as a French farming community in 1749 at Pointe de Montréal.

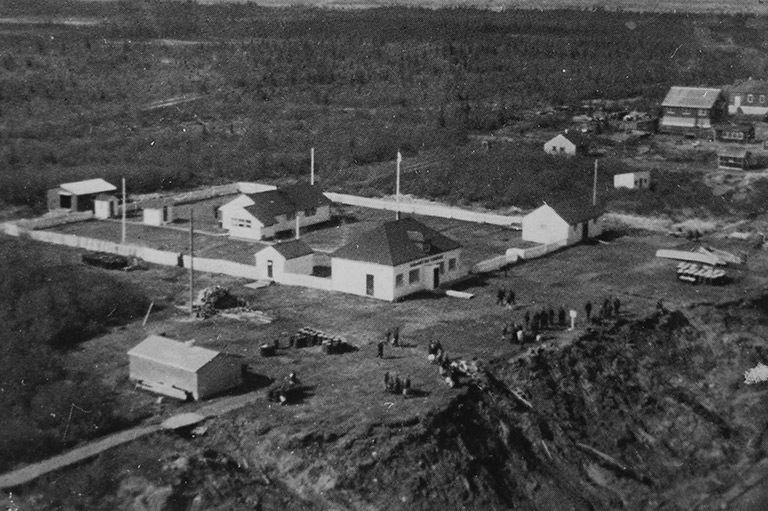

Today the vibrant community of Fort Severn Washaho First Nation has a population of some four hundred people with an elementary school and an online high school; a permanently staffed nursing station; an all-weather airport with scheduled air service five days a week; satellite phone and Internet access; and electricity, water, and sanitary services in each home (household comforts that were not widespread in many northern communities as recently as the 1980s). Its single retail outlet, the Northern Store, has been present in the community since its establishment as a Hudson’s Bay Company trading post in 1759. The store’s name only changed in the late 1980s when the HBC’s Northern Stores Division was sold to the North West Company.

Fort Severn — or Washaho in the Mushkego Cree language — has been known by a variety of names throughout its history. The HBC originally intended to call it Fort James, but that was quickly changed to Severn House, and through the years the place was often simply referred to as Severn. At some point in the mid-nineteenth century, for reasons that are still not clear, mapmakers began giving it the name Fort Severn, while official HBC correspondence continued to use Severn House for decades afterwards.

The Severn House HBC post journals — particularly the 1759–60 journal of the first factor, Humphrey Marten — contain some unique glimpses into Fort Severn’s roots. Along with Mushkego Cree oral history, these distant echoes of a place and people still reverberate, describing important events in the creation of that community, of Ontario, and, indeed, of Canada.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

The story of Fort Severn begins well before there ever was the idea of Canada. Some eight thousand years ago, following the end of the last great ice age, the glaciers had finally melted, and the salt waters of the sea had rushed in to take their place in a much-expanded Hudson Bay basin. Ever since, and still to this day, the slowly rebounding land has pushed the boundary of that inland sea further north, exposing new land to the warmth of the sun and offering new places for plants, animals, and people to live and flourish.

Ontario’s seashore has always been a unique place, and the people who lived there thousands of years ago developed an equally unique way of life that was based on an intimate knowledge of the seasonal cycles and availabilities of plants and animals. While they harvested all that the land had to offer, caribou were a key resource around which their way of life was crafted. At the end of winter, thousands of caribou leave the Subarctic boreal forest and travel to the treeless coastal areas, where they give birth and spend the summer with their newborns in the cool winds that blow off Hudson Bay. Hunters and their families would move to the coastal regions to hunt caribou but also to harvest the vast flocks of ducks and geese during their spring and fall migrations, to take fish from the rich rivers and streams, to trap small mammals, and to gather plants and medicines. Summer was the best of times.

In the fall, caribou gather into large herds and leave the coast, seeking lichen-rich wintering areas in the southern interior boreal forest of the Hudson Bay Lowlands. Hunters and their families would also relocate into these same regions, seeking out the wintering caribou herds and taking advantage of fall-spawning fish, small game, and beaver. But winters were challenging, and hardships could be expected. With the warming rays of spring, the cycle would begin anew; knowledge of the land and of how to live with it passed from generation to generation.

While pre-contact artifacts have not yet been discovered within the modern-day community of Fort Severn, such objects occur throughout the region and span many centuries, even millennia. According to Fort Severn Elders, the immediate Fort Severn area was at a crossroads of travel networks where “foot highways” — trails that followed ancient coastal beach ridges — met the banks of the inland-reaching Severn River. Undoubtedly, the people living in the region in ancient times made short stops in the immediate vicinity of Fort Severn. The area was certainly part of the Mushkego Cree traditional territory three centuries ago, at a time when the flag of France flew over the St. Lawrence Valley and the rivalries between European nations were keenly felt in these distant lands surrounding Hudson Bay.

Advertisement

At the end of the seventeenth century, newcomers from Europe appeared with an insatiable appetite for the rich furs of these northern latitudes. In 1670, the British King Charles II granted the Hudson’s Bay Company a commercial monopoly over the entire Hudson Bay watershed, albeit without the consent of the land’s inhabitants. The English called this vast territory Rupert’s Land. The company’s motto — then as today — was pro pelle cutem, roughly translated as “a pelt for a skin,” perhaps a play on words to suggest how difficult it was for the Bay men to live in this distant land and to obtain the coveted furs for the wealthy merchants back in England.

In 1685, the Hudson’s Bay Company built Fort Churchill, which soon became known as New Severn Post, on the right bank of the Severn River about five kilometres upstream from today’s Fort Severn. The area was under threat from the French, who wanted to wrest control of the Hudson Bay fur trade from their English enemies. Five years earlier, HBC Governor John Nixon had noted, “Tis probable sudden attempts may be made upon it [the trade], and we judge in no part of the Bay so likely as Port Nelson or new Severn.” In 1690, New Severn Post was in fact destroyed during an expedition into Hudson Bay by the soldier and adventurer Pierre Lemoyne d’Iberville. For the next seventy years, Mushkego Cree hunters from the Severn River region had to travel three hundred kilometres west to York Factory or six hundred kilometres east to Fort Albany if they wished to trade furs with the HBC — or they had to depend on intermediaries to do it for them.

Tensions between France and England were once again running high in 1759 — the Seven Years War was raging — and inland peddlers from Montreal were intercepting trade that would otherwise have flowed to the HBC’s bayside posts. In May of that year, the HBC’s Humphrey Marten, writing from the company’s main trading post at York Factory on the shore of Hudson Bay in present-day Manitoba, noted: “If that there is not Speedily Some Method taken to Secure Severn River from the Encroachments of the French, a very Great Loss in trade must necessarily follow.”

Marten was tasked with building a post on the Severn River. On September 4, 1759, he and nine men left York Factory aboard a small ship commanded by John Garbut and sailed “for Severn North America in Order to Erect a Settlement at that place for the Hon’ble Hudsons Bay Company.” They carried with them instructions, trade goods, tools, materials, and supplies. On September 20, exactly one week after the French defeat in the Battle of the Plains of Abraham at Quebec City, Marten recorded his first sighting of the place where he would settle: “Saw the Bluffs of Severn River,” he wrote. “Our Boat came on Board all well the Shallop at Anchore in the River.”

Two days later, Marten and his men were sought out by local Mushkego Cree hunters, who welcomed them with gifts of food, in keeping with their traditional hospitality towards travellers. “At 1/2 past one came to an Anchore in said [Severn] River,” Marten noted on September 22. “An Indian brought some dryed Meat.” A unique and mutually beneficial relationship between Severn River hunters and HBC personnel started then and there. Living in the coastal area, the Mushkego Cree hunters had access to vast quantities of migratory waterfowl and caribou. With the long winter ahead, Marten and his men required food to supplement their meagre provisions, which included oft-mentioned oatmeal and dried peas. That autumn, and for many autumns to come, the Mushkego Cree hunters brought the HBC men hundreds of geese, which they salted to preserve the meat over the winter. In exchange, the hunters received the trade goods they needed, such as axes, knives, cloth, beads, blankets, tobacco, clay pipes, muskets, powder, balls, and shot.

Marten’s orders had foreseen that the ship that brought him and his men to Severn would “be furnished with necessarys for a Log Tent.” Once all their goods and materials had been unloaded from the sloop, they set about “clearing a place to pitch a Tent” and began “making a kind of House.” This was an urgent task. The first snows arrive early in southern Hudson Bay, and Marten and his men had little time to locate adequate lumber sources and erect a permanent dwelling before the long winter set in.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

On September 25, Marten wrote to his friend James Isham, the factor at York Factory: “The Place I have pitched upon for a Fort is about 6 miles from the North Enterance of the River, the Banks are Steep, the Flood at Spring Tides rises about 9 feet.” This last statement was a great underestimation of reality, a point that would be clearly underscored in just a few months time. Marten rounded out his letter by describing the difficulties he had encountered during the trip from York Factory — both while on Hudson Bay as well as in the river — and by assuring Isham that he and his men had arrived safely. He likely dispatched the letter to his friend by means of a local person who was travelling to York Factory either on foot or by canoe.

The letter arrived at York Factory on October 4, and Isham replied on November 26 with a letter that contained some local gossip as well as information on staffing changes and goods that would be shipped in the spring. “Hope to hear some little progress in Trade, and will be a Satisfaction to hear how you now like the Situation of the River,” Isham wrote. “If Opportunity serves shall send in March or Aprill, till then rest, wishing success may attend [you].” Probably the most important aspect of the letter was that it was a link between friends. It certainly must have made the small group of HBC men at the new post feel just a bit less isolated in their far-off world at the bottom of Hudson Bay, where they were spending their first winter in tight and miserable quarters.

The haste with which the men had erected their dwelling meant that the timber had not had time to dry. “All green Logs is very damp, we are obliged to be extremely careful less they should be damag’d,” Marten wrote in his journal. Later, he took note of “the frost during the Winter having split most of the Logs.” This might have been tolerable if at least the men had been warm. But, in spite of having constructed a fireplace, in December Marten lamented: “So Cold can hardly put pen to paper, tho close to the fire.”

Marten and some of his men suffered from a number of ailments during that first winter, such as colds, gout, and rheumatism. “What I use as Medicines are Spirit Wine Camphorated, Sope, Basilicon, & Sweet Oil,” Marten noted. However, he complained: “I have not one thing Specified in the Catalouge of Medicines as a proper remedie for either a Burn or scald, which ought to have been sent in the Room of so much Flour Brimston [sulphur powder] having enough of that to set up all the match-makers of London for a Century.”

The need for a burn treatment became acute when a Mushkego Cree family came to Marten seeking help. In the ninety years since the Hudson’s Bay Company had begun establishing posts along the James Bay and Hudson Bay coasts — starting with Charles Fort on the Rupert River in 1668 — local people had become aware of the medicines that the Bay men had with them. They sometimes came to the posts in medical emergencies if they were not able to adequately treat themselves. On Christmas Day 1759 Marten recorded: “An Indian & his family came to the House the Man and one Child are most miserably scalded all over the head and neck, and almost starved with Hunger.” Marten cared for them with what little he had on hand, and toward the end of January he described them as doing “quite well.”

January is known to people in Fort Severn as the “eye of winter”— a time when temperatures regularly fall below minus thirty degrees Celsius. That month, Marten wrote: “Extreem cold can keep nothing thaw’d tho close to the Fire.” Matters were made even worse by the incredible quantities of snow that fell. In February, Marten noted: “The men all employ’d in geting the Snow from about the House we are almost Buried Alive with it.” Sprinkled throughout his journals are frequent references to hunters bringing in caribou meat or hunting migrating geese or ptarmigan for the post — no doubt a welcome reprieve from the penury of winter.

After many months, winter gradually turned to spring, and the ice began to break up on the Severn River. In the Severn — as in all of the major rivers flowing into southern Hudson Bay — ice breakup occurs earlier in the headwater region, located far to the south, than it does at the mouth of the river. This leads to large quantities of water moving down the river toward the still-frozen estuary, often causing immense ice jams to form and raising the river to dangerous flood levels in a matter of a few short hours.

Marten would have been well acquainted with this characteristic of the river when he prudently built his winter dwelling on high ground, and he would likely have watched with anxiety as the water levels rose. On May 21, 1760, Marten observed: “At 2 this morning a Large body of Ice came down the River Which fill’d it from Side to Side, after which the Water and Ice came within 3 Feet of the Top of the Bank at which hight it continued till noon when it broke a passage to the S:E:ward, & we had clear water, but before night all was fast and as full of Ice as ever.” Breakup was then, and is today, very much a wait-and-see event: Some years the ice-laden water will come very close to spilling over the riverbanks, while other years it is much less of a threat. It was likely a cause of much anxiety for not only the Bay men but for anyone living near the shores of the Severn River at that time of the year.

In the spring of 1760 Marten and his men began working on a more permanent structure, but permafrost — which occurs as a narrow band all along Northern Ontario’s Hudson Bay coastline — hampered the digging of a foundation. Marten noted: “Clearing a place for a Foundation can make but poor hand on’t, not yet thaw’d enough to get the Trees up by the roots.” In later years, entries in the post journal noted shifting of constructions and flooding of cellars, all due to the melting and destabilization of the permafrost that resulted from the elimination of the natural vegetation and the construction of buildings in the new clearing.

Along with the warming rays of spring came the herds of caribou moving into the area and incredible flocks of migrating geese and ducks. Post servants and local hunters employed by the HBC were sent out with the hope of breaking the monotonous diet. Trappers began coming in from their traplines with the winter harvests of furs. That first year saw a modest harvest of nearly 3,300 skins traded, of which there were 1,529 marten skins and 1,384 beaver skins. In addition to the lucrative furs and the promise of fresh meat came the clouds of blood-seeking insects — mostly mosquitoes and blackflies. At the end of June 1760, Marten noted: “Musketoes, as thick as they can Swarm.” Since the Bay men were already quite familiar with these pests, this journal entry must have been intended to underscore the hardships the men had to endure for the company.

The Bay men tried setting nets in the Severn River to supply themselves with fish, but these never seemed very productive. They faced stiff competition from seals and beluga whales, which fed on the same fish stocks the Bay men were after. (Until the widespread use of snowmobiles, beluga were hunted by Fort Severn residents and used to feed their dog teams.) A frustrated Marten noted in June 1760: “We cant get a Single Fish for the Dam’d Whale, they Break the Netts, and have carryed one entirely a Way.”

Another way Marten tried to increase the post’s self-sufficiency was to grow vegetables. Since Fort Severn is located at fifty-six degrees north latitude, days are quite long in the summer — on the longest day of the year, June 21, there are more than 17.5 hours of daylight. But there was one element that worked against them: permafrost, just a few centimetres below the surface. The challenge was well understood by Marten, who noted on June 10, 1760: “sow’d a few seeds, the ground thaw’d about 6 Inches.” Yields, at least during the first year at Fort Severn, were not much to write home about — in fact Marten did not record them at all in his journal. In future years, in spite of poor yields and some catastrophic ends to the gardens, vegetable plots were repeatedly planted.

Humphrey Marten stayed another year at Severn House before being appointed acting chief trader at York Factory following the death of his friend James Isham. He would later be named chief trader at Fort Albany, and later still at York Factory. He eventually retired in 1786 and is thought to have died sometime before 1792.

Advertisement

The relationship between the Mushkego Cree people and the location now called Fort Severn has evolved over the centuries since it emerged from the waters of Hudson Bay, and especially over the two and a half centuries since the human landscape was altered by the permanent presence of European traders. For nearly two centuries, provisioning the Hudson’s Bay Company post with game of all kinds became an integral part of this relationship. Without these provisions, the already challenging life of the HBC men would have been incredibly more demanding. Indeed, without these resources it is difficult to imagine that the post could have been maintained. In 1792, John Ballenden, master of Severn House, indicated, “Severn House depends entirely for provisions from the Homeguard Natives as I have never received from England more than ninety days annually of Provisions for Eighteen men.”

During the first decades of the existence of Severn House, the journals tell of small numbers of unnamed local people who spent time near the post, sometimes tending caribou snares, hunting “partridges,” or setting nets to provide fish for the HBC men. By the late nineteenth century, dwellings were constructed a short distance from the post, where people would stay when coming to trade or to spend part of the warm summer months. A stay at Fort Severn was eventually inserted into the annual cycle of fur and food harvesting.

In the mid-twentieth century, the Catholic Church established a mission, for which it required a sawmill to produce lumber to meet its building needs. This mill was also used by local people to construct permanent dwellings in the area where Fort Severn’s school is now located.

For some, the moments recorded by Humphrey Marten are fur-trader history. After all, they deal with events that took place at an English trading establishment and the hardships that he and his men endured on behalf of the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England Trading into Hudson’s Bay. At the same time, however, Marten recorded a multitude of interactions and exchanges with unnamed local people on whose lands he had erected his stockaded trading post. Their contributions to the success of Marten’s enterprise went beyond simply providing animal pelts. They literally kept the traders alive. This relationship was the core around which a community developed — a community that is still thriving more than 260 years after the first Mushkego Cree hunters shared their meat with a sloop full of English fur traders.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement