Lone Adventuress

To set out on a six thousand mile trek with no more outfit than a stout iron bar and a few dollars requires determination and courage of an unusual sort. Lillian Alling had plenty of both. Alone among the millions of New York City, this little Russian immigrant felt that she could not stand the loneliness and the nostalgia any longer.

Quietly and efficiently she laid her plans as she darted along the crowded streets, an inconspicuous little figure in her rough clothes and heavy shawl. Impossible to save enough money, from the pittance she earned at housework, to buy a steamer ticket. Then she must walk.

She was young, strong and used to hard work. It would be simple. Carefully she studied maps and chose her route. Siberia was her objective. Once there, among her own people, it would be easy to arrange passage from Vladivostok to her beloved steppes. She could almost hear the deep-toned laughs of the peasants at the market place and the tinkle of the music for the dance.

Carefully she hoarded her savings. The day came. She headed for Chicago, turning down all offers of lifts and marching smartly along the long concrete highways. Her small, lithe figure, knapsack on her back, was noticed at Minneapolis and at St. Paul and then at Winnipeg.

She was next heard of on the Yukon Telegraph trail in the northern part of B.C. The linesman, at the second cabin on the trail, stared in amazement at the slight figure of a woman, her clothes almost in rags, who gazed solemnly at him from the doorway. Travellers were rare in that remote district even in the good weather. Here it was late fall and a woman appeared.

Constable G. A. Wyman of the B.C. Provincial Police at Hazelton listened to the report of the linesman over the telephone.

“She sure is travelling light. Too light for this time of year. Her shoes are just ordinary running shoes. Her pack didn’t look any too heavy to me either,” the husky “wire-snapper” told the officer. “She left here just a while ago and it looks bad over the “hump” already.”

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Wyman thanked the man and turned to a calendar on the wall. September, 1927. Already the tops of the mountains were enshrouded in mists that crept lower every day. To venture into that uncharted wilderness as if setting off for a few hours’ hike was nothing short of suicidal.

Better to go after her now and pursuade her to return than to lead a search party through the wilds in the depths of winter, reflected Wyman as he made his preparations for the trail.

Back at Hazelton with his charge, Constable Wyman turned her over to Sergt. W. J. Service, the N.C.O. in charge of the detachment. The pathetic little figure stood before the desk, her dark, tragic eyes watching every move of this grizzled veteran of the north country.

“Sit down, Miss Alling,” said the Sergeant kindly. “Where are you headed for?”

“Siberia,” was the laconic reply.

“Isn’t it a little late to start out on such a trip,” remarked Service mildly as he glanced out of the window.

The Russian girl broke into a stream of pleading, her accent becoming more pronounced as she became more excited.

“You must not stop me. I have done nothing wrong. I am strong and can walk many miles before the snow comes. You cannot keep me back now.” Her tone was one of desperation.

Service interrupted the flow of words.

“When did you eat last?”

“I have money,” replied the girl proudly, her dark eyes flashing.

The officer made up his mind. To let this girl start out on a trail that hardy men regarded as “tough going” was impossible. Her nervous manner, her very frailty convinced him that he was right. Once, during her pleadings, he almost weakened, but a glance at the tree-covered hills and their threat of snow and bitter weather strengthened his resolve again.

Committed on a charge of vagrancy, Lillian Alling was unable to pay the fine imposed. Her total wealth consisted of $10. Her outfit, a knapsack and a few personal articles and a stout iron bar. "Protection against men,” she said when asked what it was for.

The magistrate ordered her taken to Oakalla gaol, in New Westminster. There, for the next two months, the Russian hiker obtained shelter and good food. On her release, work was found for her and once again she was able to build up a small sum in savings.

Neither the kindness of her employers nor the time spent in gaol dampened her ardour or lessened her determination to return to Russia.

Near the end of June 1928, she started off on her pilgrimage again. Sergeant A. Fairbairn, then in charge of the detachment at Smithers, was warned that she had left for his district. On the nineteenth of July she arrived at Smithers.

This is a remarkable feat. It meant that she had covered between thirty and forty miles a day.

“Did you get any rides on your trip here?” asked the Sergeant.

“I walked all the way,” replied the girl.

“You are a good traveller,” the Sergeant commented.

“But do you know anything of the country into which you are going?’’

“I am not afraid. I have come a great distance now and I must go on. I must.”

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

The Sergeant explained the dangers that would beset her trail, increasing as she moved north. The girl was undaunted. It was impossible to stop such a zealot. To reach Siberia had become an obsession with her. It was the only topic about herself that she would mention. Questioned as to her past she refused to say anything. This had been noticeable in her first attempt to go through. She was reticent in the extreme.

“I will consent to your continuing your journey on one condition.” Sergeant Fairbairn finally said.

“I will agree to anything. Just let me go on,” replied the girl.

“I want you to report to each of the cabins along the Telegraph Trail. You will have that much supervision anyway. I will know that you will be safe for a time. We will help you all we can, because we have your own safety to think of.”

The young Russian girl readily agreed to this arrangement. Every twenty miles or so along that slender strand of wire strung through the wilderness, are maintenance cabins. The linesmen stationed in these cabins were more than willing to help the wayfarer. They suggested meeting the girl half way between the stops and escorting her in. In this way she would not lack companionship on most of the trip.

Word of her progress was flashed back to Smithers. Her ability to walk was astounding. Motivated by some urge that brooked no delay, she tramped ahead at an amazing and tireless pace. Cabin after cabin reported her arrival and her quick departure.

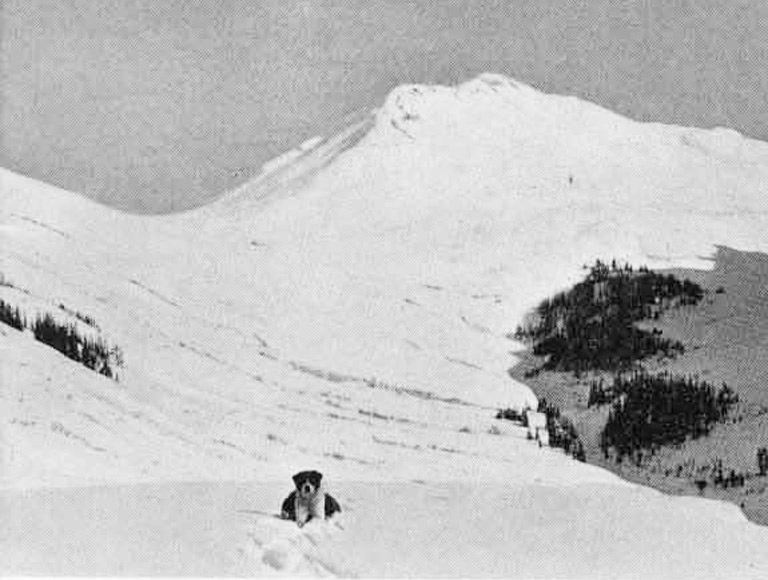

As one of the boys put it, “She sure ain’t one to talk.” Lillian did not tarry along the trail but by the time she had reached Cabin Seven the weather had turned cold. The cloudy skies and biting winds marked the approach of winter and the closing of travel. The mountainous heights of the district were often lost in fogs that blotted out the familiar landmarks and rendered travel very difficult.

A bitter wind howled around the little group of cabins and shacks that made up Post Number Eight on the trail. Jim Christie and Charlie Janze patrolled the rugged hills of this sector.

They had separate cabins and each worked a territory. Charlie was just thinking about going to his own cabin and turning in when a knock sounded at the door. Jim Christie opened the door and stepped back in amazement. There stood a woman.

“Come on in,” he stammered.

Charlie looked up from his mending job and gaped.

“You must be that girl we were told was heading this way. How did you get here so fast?” he asked.

Lillian Alling smiled fleetingly as she slung her pack to the floor and dropped into a chair beside the stove. She was about all in. The wire-snappers quickly got a meal ready for her. As the traveller ate, the men studied her furtively. Her clothing had taken some rough usage; tattered and torn, it was not much use for the trail.

Charlie gave up his cabin for the visitor’s use. He fixed up bathing facilities and even rustled a pair of boots for her. Then the pair of linesmen turned dressmakers and modistes. Out of old shirts of their own they fashioned new shirts for the traveller.

Discarded work pants were ripped, washed, patched and remade into hiking pants. The dark eyes of the Russian girl were eloquent in their thanks. For three days Lillian was the guest of the hospitable linesmen.

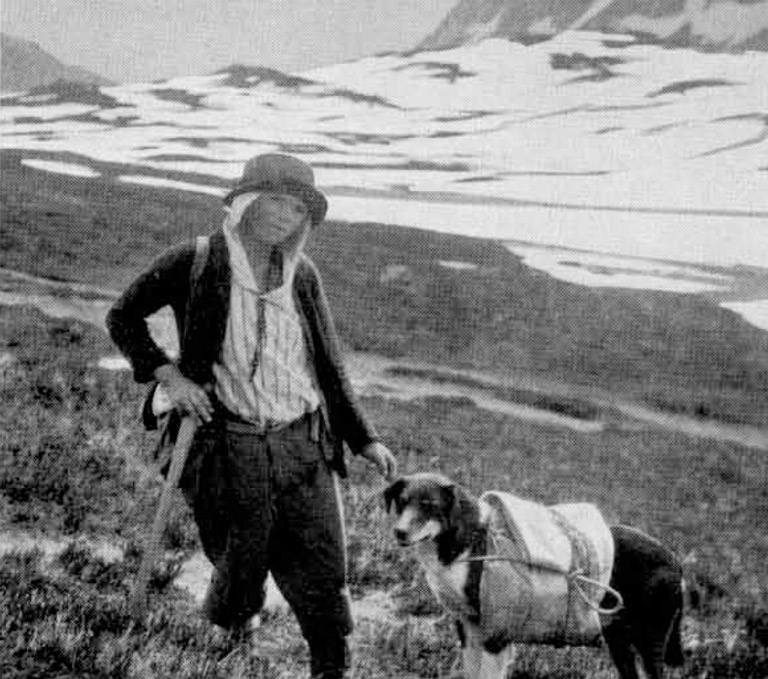

When she announced her decision of leaving, Charlie sprang his surprise. He appeared at the cabin door with a black and white mongrel dog. A sturdy little animal, he would be a great help carrying two little rucksacks slung on his back like paniers.

“It must get kind of lonely sluggin’ through the hills by yourself all the time,” he remarked rather diffidently. “This fellow will be someone to talk to anyway.”

Trouble developed on the line somewhere between Cabin Plight and Echo Lake. Charlie set out to locate it, accompanying Lillian as far as Cabin Nine. He left her there while he set off to test the wire.

At the same time, the linesmen from Echo Lake, advised of the trouble and of the departure of the hiker, had sent out a patrol. There were two men at the station, Scotty Ogilvie and Cyril Tooley, expert woodsmen, both. Scotty had elected to take this jaunt and had set off in the pouring rain singing one of the Scottish ballads for which he was famous in the north.

The going was tough. The drenching downpour made it very slippery underfoot: each shrub and tree soaked the traveller with a swishing deluge as he passed. The little Ningunsaw river had turned into a turbulent, boiling torrent. Scotty whistled when he saw the sagging curve of the hand cable at the ford.

It was a couple of feet under water already. With a grimace, he shook the water off the brim of his hat and turned to seek a better crossing place.

In the meantime, Christie had arrived at Echo Lake and had joined Tooley in waiting for Scotty’s return. As time went by and there was no sign of the missing linesman, the two became worried.

“I guess we had better go and look for that singing Scotchman,” said Christie.

“He should have been back before now,” agreed Tooley as he reached for his mackinaw.

It was a simple matter to follow the trail. It led right up to the river bank at the crossing, then it turned up-stream. A few hundred yards along the bank they came upon the story of the tragedy. A jagged scar on the edge of the bank showed where it had caved in, worn away by the rush of the swollen river. Here the trail ended abruptly.

With taut features the two men climbed down closer to the water’s edge and made their way precariously over piles of ragged driftwood. A quarter of a mile further along they came across what they feared to find.

The body of Scotty Ogilvie was wedged in the driftwood that piled up a swirling eddy at a bend in the stream. The jolly singing Scotsman had met a tragic end.

Silently the two friends buried the body and erected a cross above the grave that looked across the valley at the rugged hills that had reminded Scotty of his own native fells and glens.

On her way north again, Lillian Alling heard the news of Scotty’s death with real grief. She had never met him. She had never heard of him before. But he was one of the men who were helping her make her dearest wish come true.

He had given his life partly because of her. She paused by the heap of fresh earth and the crude cross above it. Then she turned slowly away and continued her trek.

On the rest of her trip Lillian Alling kept strictly to herself. At those little settlements or isolated farms where she stopped she told no one anything about herself.

Her very reticence lead to many wild theories and much speculation about her. These ranged all the way from a grand duchess of the revolution to a white spy closely pursued by the Bolshevists.

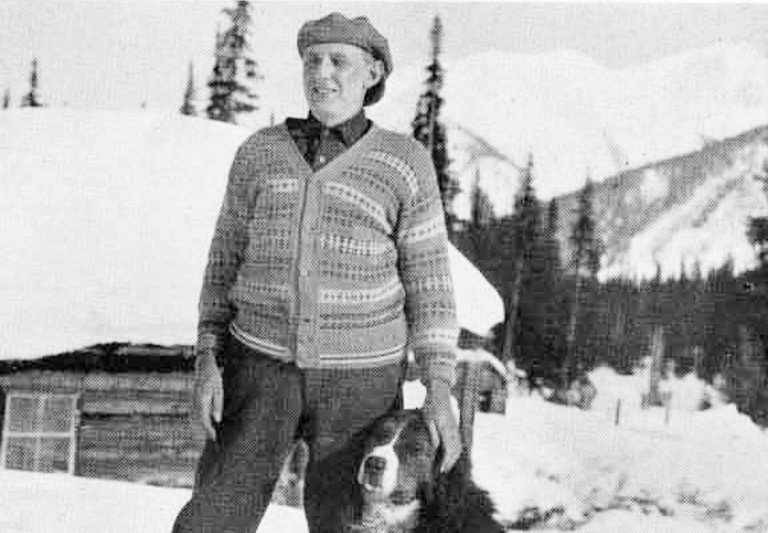

Two years later, when Lillian and Bill Albee trekked over the same route into Alaska, people were still talking of the wraith-like figure that appeared in their midst and fled as silently and as suddenly she had come.

The black and white dog, gift of Jim Christie, had met an accident before she reached Atlin. The Russian emigrée had skinned the carcass and stuffed the hide. This she carried with her, as if she could not bear to part with her one friend on the long journey.

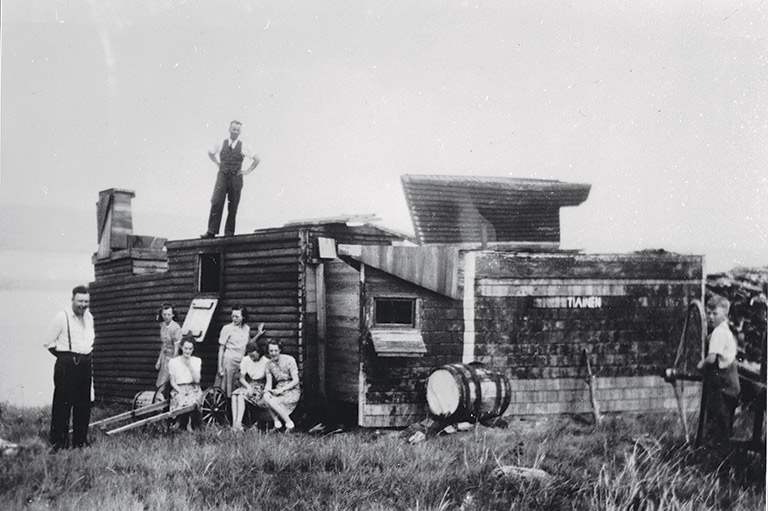

At Dawson she worked as a cook in one of the camps for the entire winter. Very little was learned of her past. She lived the life of a recluse. In the spring she launched the crude-looking boat that she had patched up during the winter months.

The last the Dawsonites saw of her was as she sat in the stern of the crazy craft, her goods piled in front of her and the carcass of her dog across her knees. Moving out right behind the ice, she faced the wide expanse of the Yukon with the same daring that had brought her safely this far.

She was reported passing through Tanana, still sitting aloof in the stern of her vessel, intent on the route that would lead her to Siberia. She arrived safely at Nome, where she abandoned the boat and purchased a few articles for land travel.

From there on her journey assumes an even deeper shade of mystery. For a time she disappeared from the ken of men. Then an Inuk brought in word that he had passed the forlorn little creature on the beach between Nome and Teller.

She had fashioned herself a small cart that she tugged along behind her. Occupying a place of honour on the jumbled mass of goods there was the stuffed body of her dog.

Beyond this report her fate is unknown. Whether she succeeded in pursuading the Inuit to take her across the Straits and thus continued on to Siberia is unknown. As far as can be ascertained on this side of the water, there on the bleak shores of Bering Strait her trail ended.

If you believe that stories of women’s history should be more widely known, help us do more.

Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share women’s stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!