The Origin of Disaster Reporting

The year 1936 was eventful for news hounds: The King was having an affair with an American divorcée and would abdicate the throne. Civil war had broken out in Spain. German troops violate the Treaty of Versailles and occupied the Rhineland. Bruno Hauptmann was executed for kidnapping and killing the Lindbergh baby. And then there was the mining disaster in Nova Scotia that became “The Rescue Heard ’Round the World.”

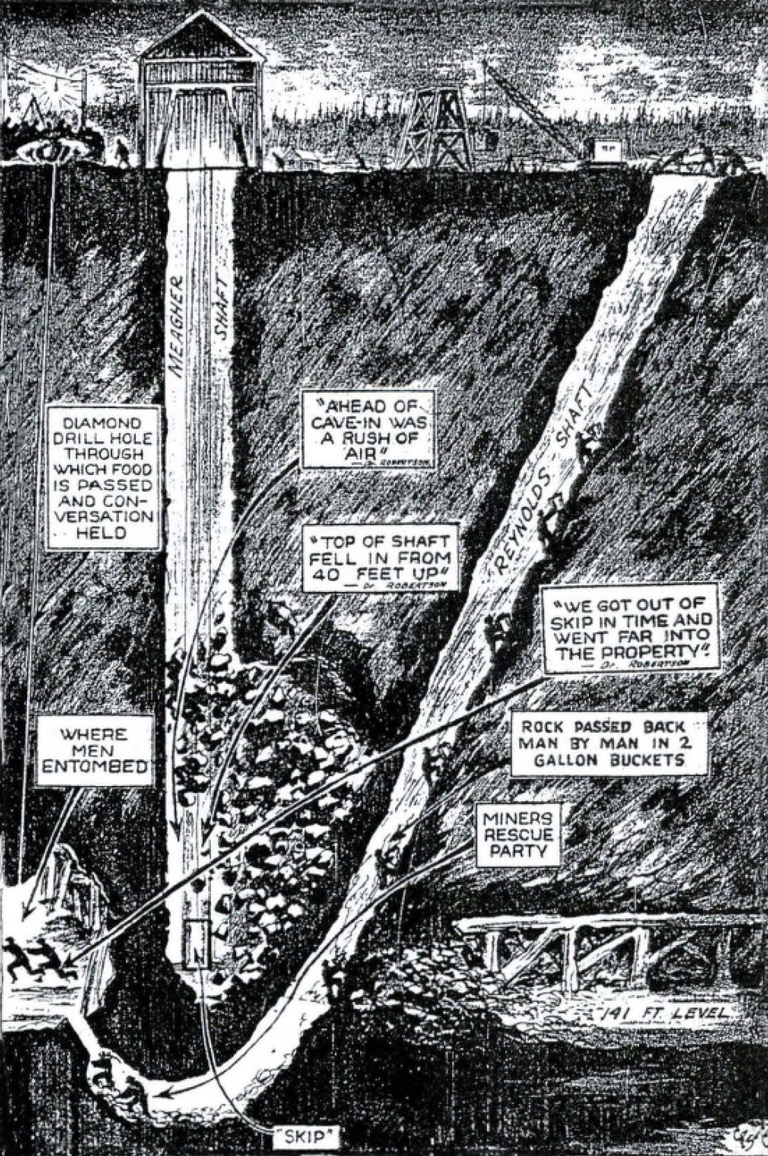

The village of Moose River, Nova Scotia, became the centre of world attention as millions of people across North America and parts of Europe waited anxiously by their radios for live, up-to-the-minute news reports on a dramatic rescue operation to save three men trapped forty-three metres below the surface of the earth in an old gold mine.

In a ten-day race against time and death, miners and draegermen slowly clawed their way through a tangle of broken timbers and fallen rocks to reach the entombed men before rising mine water snuffed out their lives.

Though Nova Scotia had known worse mining accidents with greater loss of life, the rescue would become a major media event (due in part to the Toronto origins of the three victims) that would transform radio from a largely entertainment medium to a fast, reliable news source and in the process change journalism in North America forever.

The man who would become the vehicle for this was J. Frank Willis, a Halifax native, working for the Canadian Radio Broadcasting Commission, the forerunner of the CBC.

The Moose River mine saga began on Easter Sunday evening, April 12. Two of the mine’s shareholders, Dr. David E. Robertson, the fifty-nine-year-old chief of staff at Toronto’s Sick Children’s Hospital, and Herman Russell Magill, a thirty-year-old Toronto lawyer, went into the mine around nine o’clock with the company’s forty-two-year-old timekeeper and bookkeeper, Charles Alfred Scadding, for an inspection tour pending a possible sale of the mine to New York interests.

Two hours later, while the three were waiting at the forty-three-metre level for the hoist to return them to the surface, the mine’s roof came crashing down, trapping them in a small chamber without heat, light, food, or water.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Prior to the cave-in, few people had heard of Moose River, a small village one hundred kilometres east of Halifax. Gold mining had been a periodic venture there for more than a half-century until the Moose River Syndicate was created with Robertson and Magill as principal shareholders. Magill and Scadding had moved to Moose River in January to supervise the dewatering of the mine. Robertson arrived only the day before to inspect the work carried out to date.

When the mine collapsed, no one seriously believed the trapped men were still alive. Those who rushed to the pithead to help with the rescue thought they were going down the shaft to retrieve bodies. But the men below lit a fire with wood from empty dynamite boxes; the smoke, drifting up through cracks in the earth, signalled that they were still alive. By blowing on the embers, they kept the fire going for the next eighteen hours.

Planeloads of Toronto reporters flooded into Nova Scotia, hotly pursued by other reporters from papers across Canada and the United States.

When news of the accident reached Halifax, reporters from the Halifax papers, Canadian Press, and radio station CHNS rushed to the scene. The next day, planeloads of Toronto reporters flooded into Nova Scotia, hotly pursued by other reporters from papers across Canada and the United States.

The sudden influx put a severe strain on the single telephone line out of Moose River, sometimes leading to fistfights among the press corps. Mines Minister Michael Dwyer devised a scheduling system allowing newspapers use of the telephone for five minutes each hour and the radio station the use of the phone for three minutes every half hour.

There was a notable absence, however: J. Frank Willis, of the Halifax office of the CRBC. His bosses in Ottawa refused him permission to go to Moose River.

By Monday evening, rescue workers arriving from across Nova Scotia and Northern Ontario were severely hampered by the dropping temperatures and icy winds. Roads had turned into a muddy soup.

Two days later, Billy Bell, the provincial government’s diamond driller, was ordered to the scene. Thursday at noon, with 150 rescue workers in attendance and an emergency field hospital ready and waiting, he and his three-man crew began drilling.

On Saturday, April 18, at 1:30 PM., a little more than forty-eight hours after the drilling began, Bell and his crew broke through into the chamber where the men were trapped. They removed the drill rods and Bell shouted down the pipe several times, but received no reply.

Convinced that the three men were dead, those in charge of the rescue ordered Bell to remove his equipment and return to New Glasgow. But Bell disobeyed and remained on the job. He tried sending a bright red flare down the drill pipe, but there was no response.

Then, shortly after midnight, he hooked up a steam whistle and sent down a shrill, piercing blast. Listening at the opening, he finally heard a faint tapping at the other end of the pipe.

The news of the break-through sent newspapers in Canada and the United States rushing out extra editions with bold headlines informing their readers that the men were still alive. All three were wet, cold, and suffering severe stomach cramps from lack of food, the reports said; Magill was in the worst shape.

The drill pipe became a lifeline through which candles, matches, chocolate, hot soup, medicine, and brandy were lowered down to the trapped men. In time, a small microphone was sent down the pipe so they could talk to their anxious wives and their rescuers.

Meanwhile, water in the lower mine workings — rising at an alarming rate — threatened to drown them before the rescuers could reach them. Then, on Monday morning, Magill died of pneumonia. For him the long ordeal was over.

Meanwhile, Frank Willis cooled his heels in his Halifax office. Again he telephoned his bosses in Ottawa for permission to go to the mine site and again was told to stay put. Finally, late Monday morning, April 20, eight days after the cave-in, Willis received a call from Ottawa granting him permission to go to the scene and broadcast.

Arrangements were made with Maritime Tel and Tel and Canadian Pacific Telegraph to clear and maintain lines for broadcast. By noon, Willis, two technicians, his equipment, and a table microphone were on their way by car to Moose River.

He wasn’t graciously received by the newsmen who had been there for the past week. They knew his broadcasts to radio stations across Canada and the United States would eliminate their almost exclusive newspaper coverage. They were doubly upset when they learned that he was to be patched directly into the telephone system.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

At 6 P.M. that evening Willis made his first broadcast to fifty-eight CRBC stations across Canada and 650 stations in the United States. The BBC in London also picked up the broadcasts for Great Britain and Europe. This massive hookup of radio stations made radio history in North America.

His first broadcast, bringing his vast radio audience up to date, lasted almost fifteen minutes and was considered one of the longest on record. It began with the words “This is the Canadian Radio Commission broadcasting from Moose River, Halifax County.”

From then until midnight, two-minute reports were broadcast every half hour informing listeners on the plight of the men and the progress of the rescue operation. Some sponsors in the United States shortened their programs by two minutes in order to carry his live news reports.

An estimated 100 million people across North America stayed by their radios to listen.

Finally, at 11:40 P.M. on Wednesday, April 22, the rescue workers broke into the underground chamber that held the two remaining survivors. A little over an hour later, Dr. Robertson appeared on the surface. After embracing his wife and thanking his rescuers, he was hurried off to the nearby field hospital.

Members of the Salvation Army, who had arrived over muddy, rutted roads the day before to make coffee and pass out doughnuts, led the rescue workers in singing “Praise God From Whom All Blessings Flow.”

About sixteen minutes later Scadding arrived on the surface and was also rushed to the field hospital. Two of the rescue workers returned down the mine to retrieve Magill’s body.

Willis broadcast the happy news to the world that the men were alive and back on the surface after a ten-day ordeal. He made his final broadcast at 2:00 A.M. on Thursday morning.

In all, he made ninety-nine broadcasts, a record for on-the-spot news coverage. In doing so, he helped make radio more than just a source of entertainment — he made it a quick, reliable news medium. Within hours, reporters filed their final stories, packed their gear, and headed to Halifax to catch planes home, returning Moose River to its former obscurity.

Eight years after his rescue, Robertson died in Toronto. Scadding, who died in the early 1960s, said that if it were not for the newspapers and the radio they might not have been saved. While most of the officials in charge of the rescue had given them up for dead, the news media had so aroused the public that abandoning the rescue would have been ill-advised.

Willis, suddenly popular, was deluged with lucrative offers from the United States to make endorsements and public appearances, but he refused. Two years after Moose River, he went to Australia as an exchange producer with the Australian Broadcasting Commission.

In 1939, he returned to CBC’s Toronto office where he produced radio documentaries. From 1958 to 1963 he appeared as host of several television public affairs programs. He died at his Toronto home on October 26, 1969, from a heart attack.

Today a stone cairn and bronze plaque mark the site where the heroic rescue captivated millions of radio listeners across North America for ten days and created a new type of journalism. Canadian Press voted the Moose River mine rescue the top radio news story for the first half of the twentieth century. The genesis of today’s live, on-the-spot coverage of world events lies in the small mining village of Moose River, Nova Scotia.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!