Shots Fired

Editor's note: This article originally appeared in the Winter 2025 issue. When we went to press in mid-October, Canada still had its measles elimination status. Since then, the country has lost that designation, but you won't see that update reflected in this article.

In April 2025, Morgan Birch of Fort Saskatchewan, Alta., was awakened in the middle of the night by her four-month-old daughter screaming.

Baby Kimie had been feverish for about five days — a symptom the infant’s health-care providers said was probably a side-effect of the routine immunizations Kimie had received just before getting sick. But that night, a rash had begun to blossom on the baby’s torso and she was clearly miserable.

“I was scared,” recalls Birch. “At first, doctors thought it was a heat rash from the fever; then, it spread to her face. Her eyes were almost swollen shut and she wasn’t eating.”

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

The baby’s great-grandmother recognized the illness before lab tests confirmed her diagnosis was correct: Kimie had measles. She wasn’t yet protected by immunization since the first routine dose of measles vaccine is usually given at 12 months. “I was shocked,” says Birch. “I couldn’t understand how she would get measles in 2025.”

However, Kimie is among the more than 5,000 Canadians known to have been infected with measles in 2025 as of early October; tragically, that includes two premature infants, one each in Alberta and Ontario, who died after contracting measles in the womb; the latter had other serious medical complications. We’ve also hit another terrible milestone: Since Jan. 1, 2025, our country has racked up the highest incidence of measles per million population in North America. In late July, the incidence rate of measles in Canada reached approximately 100 cases per million people, compared with an average of 2.2 cases per million between 2015 and 2019. And this is only what has been reported. “We’re not capturing them all — not even close,” says Dr. Marina Salvadori, a pediatric infectious disease specialist and a senior medical adviser for the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Stats like these would have seemed unthinkable not so long ago because the disease was declared eliminated in Canada in 1998. A contagious disease is considered eliminated if it’s almost entirely preventable — typically by vaccination — and “does not circulate in your region for more than 12 months,” explains Salvadori. In the case of measles, which is one of the most contagious human diseases ever known, roughly 95 per cent of the population needs to be fully vaccinated to prevent it from spreading to the wider community if an occasional person gets infected with the illness.

Before routine vaccination against measles began in 1970, the disease was so common that virtually everyone contracted it during childhood. In the pre-vaccination days, Canada saw an average of 54,584 cases per annum; by 1972, the number of cases dropped to just 14 a year. Other childhood diseases saw a similar reduction after routine vaccination was adopted: pertussis (whooping cough) cases dropped 87 per cent; mumps fell by 98 per cent; diphtheria and rubella decreased by more than 99 per cent; and polio came down 100 per cent.

“We’ve done a great job with vaccines, which are probably second only to clean water, the best and most impactful public health intervention” of all time, notes Dr. Shelly Bolotin, the director of the Centre for Vaccine Preventable Diseases at the University of Toronto’s Dalla Lana School of Public Health.

While Canada deserves kudos for its pioneering contributions to vaccine development and for the oft-unsung efforts to get people vaccinated, an incomplete understanding of the history of vaccines and the protection they offer threatens that success.

“Young parents are overloaded with information, and lack real context about what each of these diseases means to them and their kids”

Advertisement

Too successful?

Only a small and shrinking proportion of the population remembers what it was like to live through outbreaks of what were common childhood illnesses. “We now have at least three generations of people who have received a measles vaccine,” says Heather MacDougall, PhD, an associate professor emeritus of history at the University of Waterloo in Waterloo, Ont., and an expert on the history of measles vaccination in Canada.

“Some people think it’s not going to happen here or it’s not going to happen to my child,” says Dr. Manish Sadarangani, the director of the Vaccine Evaluation Center at the BC Children’s Hospital Research Institute in Vancouver. That line of thinking is far from new. An April 1946 “Homemaker” column in the Globe and Mail, for example, warned against being complacent about the threat of diphtheria, long after the 1930 introduction of routine vaccination. “Don’t leave it to other mothers to keep your child safe,” the unnamed author cautioned.

Christopher Rutty, PhD, a public health historian and adjunct professor at the University of Toronto’s Dalla Lana School of Public Health, agrees that vaccines are a victim of their own success. “Young parents are overloaded with information and lack real context about what each of these diseases means to them and their kids, which is why history is so important,” he says. Even for those of us old enough to remember a neighbourhood kid dying from measles during our childhood, it’s almost impossible to imagine what life was like before most vaccines existed.

How bad was it?

The first vaccine in Canada arrived in 1800 — it was for smallpox. One of the deadliest diseases known to humans, smallpox initially appeared in New France in 1616. Periodic epidemics caused death and devastation for many decades, disproportionately affecting Indigenous communities, which had no natural immunity to this disease brought to North America by settlers. In some of these First Nations communities, more than 75 per cent of the people died from smallpox.

The viral disease started with flu-like symptoms. It then caused rashes and blisters inside the mouth and on the skin that filled with pus and burst. Smallpox typically was fatal in 30 per cent or more cases. It could also cause such serious complications as blindness.

But long before Confederation, variolation — a precursor to vaccination — was used to protect against smallpox, starting in British-held Quebec in 1765. Uptake of variolation, and then smallpox vaccination, was limited and uneven, though some jurisdictions made the latter compulsory, such as the Province of Canada and Prince Edward Island in the 1860s, and Quebec in 1875. But acceptance wasn’t uniform.

Movements against vaccination aren’t a recent phenomenon. For instance, while variolation was fairly well accepted in what is now Canada, some colonies in pre-Revolutionary America passed laws against the practice. The motivations for that resistance may be familiar: religious freedom and distrust of authority.

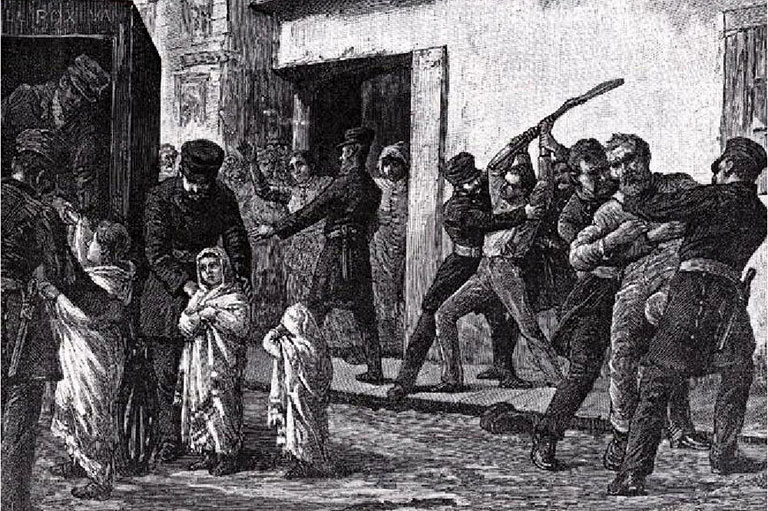

There was also homegrown opposition to mandatory vaccination. By 1885, several factors came together to create the perfect conditions for the disease nicknamed the “speckled monster” to surge in Montreal. Because many anglophone employers pushed for compulsory vaccination, some of the predominantly francophone workforce saw it as a weapon against French Canadians. A tainted batch of vaccine, which caused a suspension of the city’s original vaccination program, further undermined trust. With only one in six residents protected by vaccination, the disease rapidly spread after two infected individuals arrived from Chicago. The disease raged through Montreal and the rest of Quebec, infecting 19,905 people (3,154 in Montreal alone) and killing nearly 6,000.

Back in 1900, the leading causes of death overall in the U.S. (and, presumably, in Canada) were pneumonia, tuberculosis, diarrhea and intestinal infections, and diphtheria, which when combined, accounted for one-third of all deaths. And of those who died from these causes, 40 per cent were children younger than five.

At the time, pertussis — the so-called 100-day cough — killed five out of every 1,000 Canadian children ahead of their fifth birthdays, most of them before the age of one. Severe cases could also cause permanent lung damage, hernias, brain damage and blindness. Living through the illness was an ordeal for everyone in the household; whole families had to quarantine for weeks, which could result in lost wages and employment. A December 1934 Toronto Star article quoted the parent of an 18-month-old with whooping cough as saying, “Every little while, especially around midnight or two o’clock in the morning, he is ripped and wracked and torn by incredible storms of coughing and pain, and everyone is awake and terrified in the night.” Even as late as 1943, roughly 15,000 children per year suffered through whooping cough in Canada.

Up until the mid-1920s, diphtheria — then commonly referred to as “the strangler” — was the leading cause of death in Canadian children. The bacterial infection got its nickname from the thick, grey membrane that forms over the throat and nasal passages, eventually blocking the airways. Stricken families might lose multiple children, as was recounted in a Christmas Day 1901 story in the Globe and Mail, with the dateline London, Ont.: “Within a month, Mr. and Mrs. George Constable … have lost four children by diphtheria.”

From the 1910s until the mid-50s, outbreaks of polio (also known then as infantile paralysis) occurred relatively regularly, along with periodic epidemics. A wave of large polio epidemics struck Manitoba, then Saskatchewan and Ontario between 1936 and 1937. In the latter year, nearly 4,000 Canadians contracted the disease.

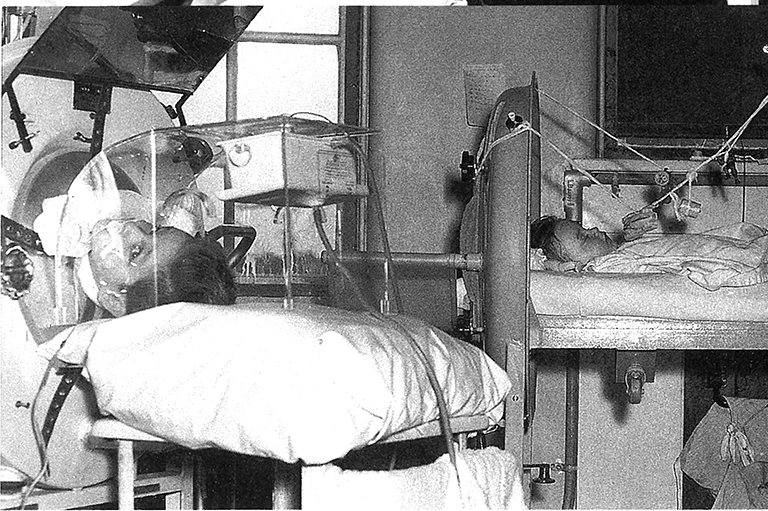

Initially infecting the gastrointestinal tract, poliovirus can sometimes enter the bloodstream and attack motor neurons in the spinal cord, which stops nerve impulses from getting to certain muscles. The result of this: 0.5 per cent of those infected develop weakness, and in some cases, paralysis so severe that the person can’t breathe. By 1934, polio was responsible for nearly half of disability cases in Canada. In 1930, the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto acquired the country’s first iron lung, a machine that could mechanically inflate the lungs of affected individuals; in 1937, the hospital assembled another 26 of those devices within a six-week period.

“No children played on the city streets,” a September 1987 Toronto Star story recalls of what life was like in the city at that time. “Healthy children were confined to their backyards and didn’t go back to school until Thanksgiving. Sick children languished in bed for six months to a year.” A then-60-year-old polio survivor named Henry Ford said in the article that the experience of being sick and unable to see his parents while in hospital was “terrifying.”

The worst spate of polio outbreaks took place between 1949 and 1954 — and paralyzed 11,000 Canadians. The disease peaked here in 1953, infecting 9,000 and killing 500. The rate of severe cases was unusually high among young adults, some of whom were pregnant and gave birth while confined to an iron lung.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

A record of innovation

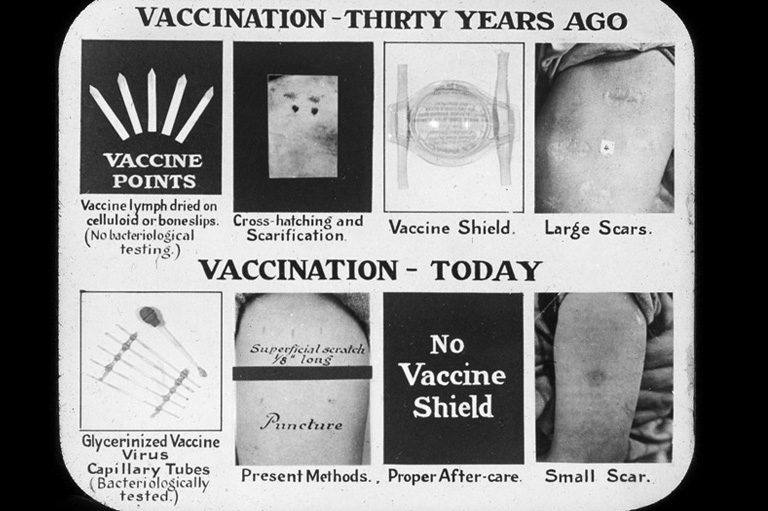

In the wake of the devastating 1885 Quebec smallpox outbreak, the Ontario Vaccine Farm in Palmerston, Ont., founded by a local physician, Dr. Alexander Stewart, began producing smallpox vaccine. First, Stewart introduced a relative of the smallpox bacteria into calves. Instruments called “points” were coated with fluid from blisters that formed on the animals’ skin. Vaccination was done by scratching a person’s skin with a treated point. The Ontario Vaccine Farm sold large quantities of its product to local health boards. Stewart later joined the University of Toronto’s department of hygiene, where, in 1913, he began to produce the first made-in-Canada vaccine for treating rabies.

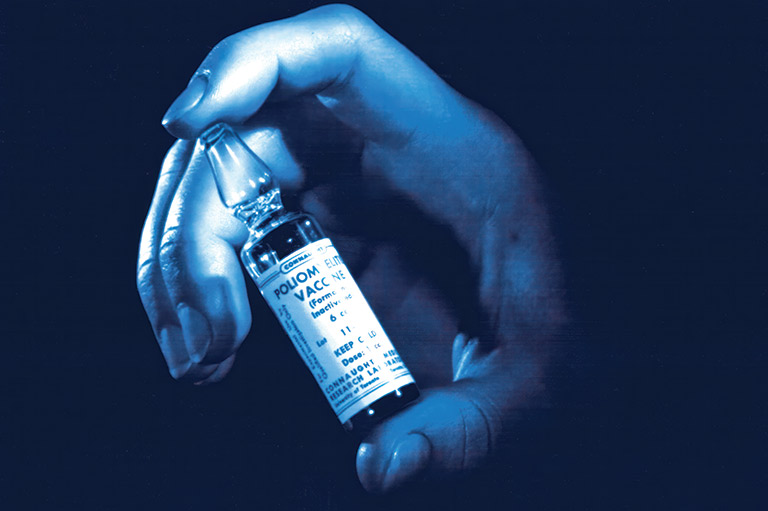

During the First World War, the not-for-profit Antitoxin Laboratory took over Canadian smallpox vaccine production because of increased demand from the military. The lab was established by Toronto physician John G. FitzGerald, who was the first person to produce diphtheria toxoid — a pre-vaccine-era treatment for diphtheria — in Canada. The Antitoxin Laboratory was the forerunner of Connaught Laboratories (later, Connaught Medical Research Laboratories) and the first facility in the country to mass produce a safer version of the vaccine with a longer shelf life.

The worst polio outbreaks took place between 1949 and 1954 — and paralyzed 11,000 Canadians

In 1918, New York City’s department of health shared an experimental influenza vaccine with Connaught to help stem the spread of the deadly epidemic sweeping the globe. Connaught operated around the clock to produce a free supply for organizations across Canada, several U.S. states and Great Britain. The following year, Connaught started making the country’s first supply of an early pertussis vaccine. In the 1920s, Connaught and Canada made their mark internationally in the fight against diphtheria when the lab’s resident diphtheria toxin expert, Dr. Peter Moloney, began preparing a new toxoid based on findings from a researcher at the Pasteur Institute in Paris.

By 1929, large-scale research projects that involved approximately 36,000 children had demonstrated that three doses of toxoid reduced diphtheria incidence by at least 90 per cent. This was “the first statistical demonstration of the value of a non-living vaccine in preventing a specific disease,” Christopher Rutty and Sue C. Sullivan write in This Is Public Health: A Canadian History.

According to the Museum of Health Care’s online exhibit Vaccines & Immunization: Epidemics, Prevention & Canadian Innovation, “diphtheria toxoid was the first modern vaccine, the first paediatric vaccine, and provided the foundation of public health immunization programs in Canada and elsewhere.” During the 1940s, Connaught was instrumental in developing combination vaccines that protected against diphtheria, pertussis and tetanus in one shot.

Canada also made key contributions in the development and testing of polio vaccine. “It wouldn’t exist without us,” says Rutty. A synthetic nutrient base, called Medium 199, created by Connaught scientists led by Drs. Raymond Parker and Joseph Morgan, made it possible to efficiently grow the type of cells needed to produce a vaccine. “With Medium 199, [Jonas] Salk was able to do a human test on his kids, himself and then people who had already had polio,” explains Rutty. “That was a major breakthrough.”

The next problem was “how to make a hell of a lot of the vaccine,” he notes. The answer: an innovation dubbed “the Toronto Method,” pioneered a decade earlier by Connaught scientist Dr. Leone Farrell for the pertussis vaccine. “Dr. Farrell adapted that technology to grow poliovirus on a large scale,” says Rutty. The technique was so successful that Connaught could provide enough poliovirus fluids to make all of the vaccine used in a landmark 1.8-million-person trial in 1954. By April 1955, the results of that study were in: The vaccine was 60 to 90 per cent effective at protecting against polio infection, depending on the strain of virus.

Since that watershed moment, Canadian scientists have continued to make contributions to inventions often hailed as among humanity’s greatest achievements. These innovations include pioneering several combination vaccines that protect against polio and multiple other infections, developing an Ebola vaccine and laying the groundwork for creating the lipid nanoparticles used in some COVID-19 shots.

Why skip the shot?

How could a country that’s made such incredible strides in vaccine science and public health end up amid a measles epidemic nearly 30 years after its elimination? For one thing, some health-system issues play a role in delaying or making vaccine access more difficult. COVID-19 restrictions created a backlog of missed and delayed medical appointments that we still haven’t caught up with. Our system for delivering childhood vaccines was created when kids got their shots for just six diseases versus today’s much more complex schedule. Meanwhile, the most powerful weapon against vaccine hesitancy is a trusted health-care provider, yet one in five Canadians lack a regular family doctor or nurse practitioner.

Then, there’s the fact that some communities have legitimate reasons to mistrust the medical establishment and government, which can lead to vaccine hesitancy. For instance, Canada has subjected some Indigenous Peoples to experimentation and procedures without their knowledge or consent. Research trials of a then-controversial tuberculosis vaccine conducted on First Nations infants in Saskatchewan during the 1930s and ’40s is just one such example.

Some communities have legitimate reasons to mistrust the medical system

Catherine Carstairs, a professor of history at the University of Guelph, also points to a change in parenting philosophy. “It was based on this idea that the individual health needs of your particular child should be your primary concern,” she says. “For example, if my child spikes a fever, what impact could that have?” Since vaccination was so successful at keeping preventable diseases at bay, and most people outside of the medical field are very poor at assessing the magnitude of benefits of vaccination versus possible harms, “it was very easy for parents to focus on what the risks might be of the vaccine,” says Carstairs.

Arguably one of the most potent negative influences on vaccine hesitancy, however, is what some experts describe as a crisis of disinformation and misinformation enabled by the internet and social media. While, according to Carstairs, the modern anti-vaccination movement in Canada began in the 1980s, today, the vaccination pushback is much more complex. Wellness influencers and others who peddle products for profit not backed by scientific evidence, podcasters who promote conspiracy theories and politicians who use opposition to vaccination as an ideological flag are just a few sources of anti-vaccine rhetoric.

In a June 2025 CBC Radio interview, Dr. Mark Joffe, Alberta’s former chief medical officer of health, pointed to widespread dissemination of dis- and misinformation by such sources as a main driver behind the roughly decade-long decline in childhood vaccination rates. “The population is confused. They’re unsure where to get information. They’re unsure what to trust,” he said. Thanks to Canada’s past success in eliminating measles, “[people] don’t understand what measles is … so [they] have forgotten about it.”

The result? In 2024, only 68 per cent of Alberta’s two-year-olds had gotten the necessary two doses of measles, mumps and rubella vaccine.

Experts expect that the current measles outbreak will eventually settle down as more people become immune either through vaccination or infection. In the meantime, “one of my worst fears is that we will continue to have large numbers of infected children and adults … and that we will see the complications of measles that we’re very familiar with,” noted Joffe.

The most concerning thing about the measles resurgence, however, is what it could signal for the future. “My mentor, Dr. Natasha Crowcroft, calls measles the canary in the coal mine,” says U of T’s Dr. Shelly Bolotin. “Because when systems break down, that’s what you see first, because it’s so infectious. What we should be thinking about is, if we’re seeing this much measles, what else are people not immune to?”

A potentially devastating disease

Even with the best modern medical care, measles can have serious consequences, with children under the age of five disproportionately affected. One impact of the disease is what’s called “immune amnesia,” where the virus causes a huge dip in your immune system’s ability to fight infections. This means that “in the ensuing two to three months, you can get bacterial infections,” says Dr. Marina Salvadori, a senior medical adviser for the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Other risks include:

- a one-in-10 chance of ear infection, with the potential for hearing loss;

- one-in-20 odds of pneumonia (the most common cause of measles-related death);

- one case of brain swelling (which can lead to lasting disability) for each 1,000 cases;

- a rare, universally fatal complication called subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE), which can occur seven to 10 years after a child has recovered from measles. SSPE affects between four and 11 of 100,000 infected children, most commonly among those who caught measles before one year of age, and causes dementia-like symptoms before the child tragically dies.

At Canada’s History, we highlight our nation’s past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, while understanding that diverse past experiences can shape multiple perceptions of our history.

Canada’s History is a registered charity. Generous contributions from readers like you help us explore and celebrate Canada’s diverse stories and make them accessible to all through our free online content.

Please donate to Canada’s History today. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement