Victoria, B.C.: Unearthing an intersection of cultures

In 1849, the British government granted the new colony of Vancouver Island to the Hudson’s Bay Company in return for the company’s agreement to bring out colonists.

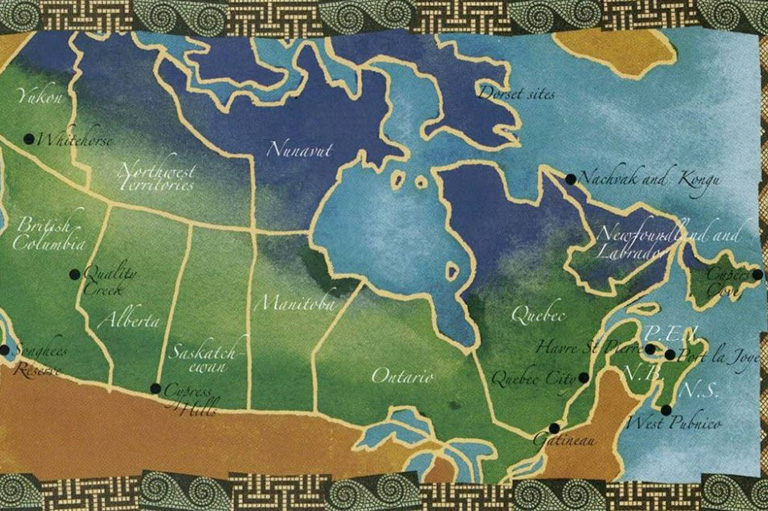

The Songhees people, who spoke a dialect of the North Straits Salish language, occupied the area surrounding Fort Victoria, which HBC chief factor James Douglas began constructing in 1843. Also referred to as Songies or Songish, they had become a vital part of the fort’s bustling new economy.

In the years since Douglas, later governor of Vancouver Island and of British Columbia, had steamed into their harbour aboard the SS Beaver, the Songhees had proved themselves to be an industrious people, providing the inhabitants of the fort and surrounding areas with valuable seasonal provisions and labour.

The women sold potatoes, clams, fish and handmade baskets, or worked in the employ of colonial households. Men provided game and labour to clear land, build fences and construct houses.

In 1852 the Songhees comprised the majority of the construction crew building a new road west to Sooke, earning $8 a month, replacing workers who had moved on to seek their fortunes in the goldfields.

Soon their culture was showing telltale signs of European influence: the woven dog-hair blankets gave way to European-style blankets; by the 1860s traditional shed-roof lodges were being replaced with more European-style houses.

Many resided near the fort, but after a suspicious fire in a wooded area in 1844, authorities asked them to establish a village on the other side of the harbour. By the following year about 70 families resided in the village.

The thriving economy in Fort Victoria began attracting large numbers of First Nations groups from the north and south in search of trade. Though the interaction among the tribes was not always agreeable, the broader variety of trade goods supplemented that which the Songhees could provide.

Apart from clashes with visiting First Nations groups and the odd local upheaval, the Songhees appeared content. But the growing number of new settlers was bursting the seams of the fort and surrounding areas, increasing the demand for land and pressuring officials to move the Songhees even further away.

In 1850, Douglas began the first treaty negotiations. Disparate opinions were heard among the colonists, and newspapers of the day continually monitored the latest development in the “Indian problem.”

After 1860, colonial businessmen rented portions of the village, by then called the Songhees Reserve, establishing businesses and employing Songhees.

In 1888 the Esquimalt and Nanaimo Railway Company built a rail line through the Songhees Reserve, providing monetary compensation to any Songhees who were forced to move from the right of way.

In the ensuing years, the Songhees refused several offers to purchase their reserve land, unhappy with any lands proposed as replacement.

Finally, in 1911, bowing to pressure from government officials and landowners, the Songhees relinquished the Old Songhees Reserve land in return for money and a slightly larger portion of land (163 acres) in Esquimalt Harbour, four kilometres east.

Following more than 90 years of industrial activity, the waterfront land of the old reserve, which had become known as Victoria West, caught the eye of local developer Westbank Projects Corporation.

Planning to erect condominiums on three acres, it hired archaeologist Ian Wilson to examine the site. Wilson didn’t anticipate finding anything of much interest, but he was proven wrong when his excavations began in spring 2005.

Working alongside several Songhees and Esquimalt First Nations archaeologists, Wilson and his crew found a cistern dating to the early 1840s. Deep and waterlogged, it held numerous well-preserved objects, including more than 100 pairs of locally manufactured boots and shoes and northern Tlingit and Haida basketry.

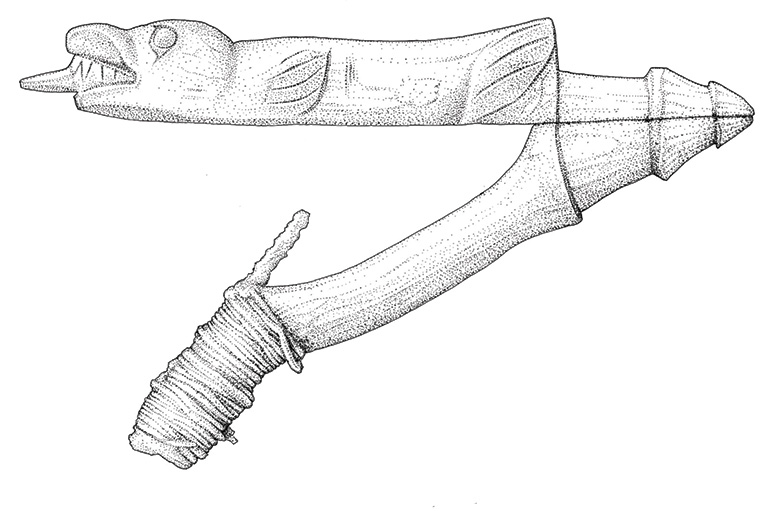

One prized artifact, a wooden halibut hook, about two feet long and carved in the shape of a seal swallowing a halibut, is believed to be of Tlingit or Haida origin. Wilson speculates that these objects were thrown into the cistern during a clean-up after an 1856 epidemic of smallpox in the village.

Though several pre-historic Songhees sites in the area had been excavated, this appears to be the largest find of artifacts from the historic period between 1845 and 1855.

Modern condos will eventually sit on the land the Songhees once called home, but archaeologists have saved this glimpse into how their culture intersected with the Europeans who arrived on their doorstep.

For more information on the history and traditions of the Coast Salish, including the Songhees, visit The Bill Reid Centre.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement