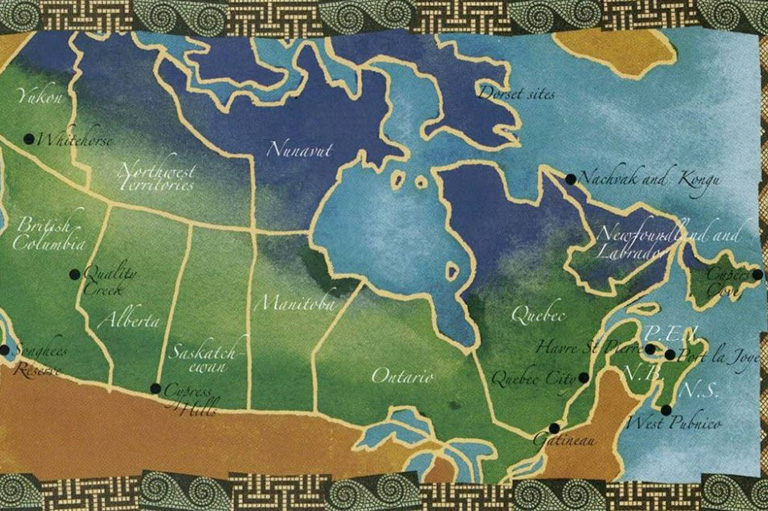

Nachvak and Kongu, Labrador: A New Design

More than 400 years ago, where Nachvak Fjord slices through the mountains rising out of the sea on Labrador’s northern coast, pioneering groups of Inuit established a winter village in an environment vastly different from anything they had known.

Driven by the advancement of the Little Ice Age (approximately 1400 to 1900), which disrupted the migration patterns of the bow-head whale, their main food source, some Inuit migrated south from the Central and High Arctic seeking a less tenuous life.

At Nachvak they followed their traditional living patterns, constructing circular semi-subterranean houses with flagstone floors and stone walls. Whale bone or driftwood draped with hides and covered with sod formed the roofs.

Inhabitants, traditionally one or two families, entered the house through a sunken tunnel that acted as a cold-trap. Inside were raised sleeping platforms and a raised lampstand to hold their soapstone lamps.

Labrador’s new inhabitants did less whaling, as the migrating bowhead were less accessible from shore and conditions of the late fall whaling season were particularly challenging. Instead, there was a greater reliance on Arctic char, ringed and harp seals, walrus and caribou.

Closer to the mouth of Nachvak Fjord, at a site known as Kongu, evidence shows that 200 years later a significant change occurred in Inuit culture, economy and social habits.

Contact with European whalers and explorers became more frequent. In 1771, Moravian missionaries, whose major objective was to lead the Inuit away from their indigenous religious beliefs, succeeded in establishing a permanent settlement further south at Nain.

Members of a Protestant sect, the Moravians had sailed from London in a second attempt at settlement following the mysterious disappearance of four missionaries in 1752. This increased European contact caused a substantial shift in Inuit culture.

Peter Whitridge, assistant professor of archaeology at Memorial University in St. John’s, Nfld., has studied the Inuit for years, excavating their village sites and following them from their home in the higher Arctic down to Labrador’s shores.

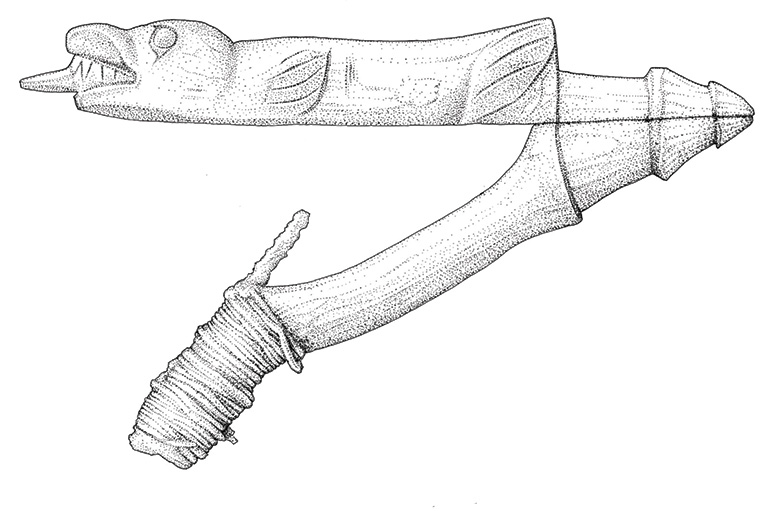

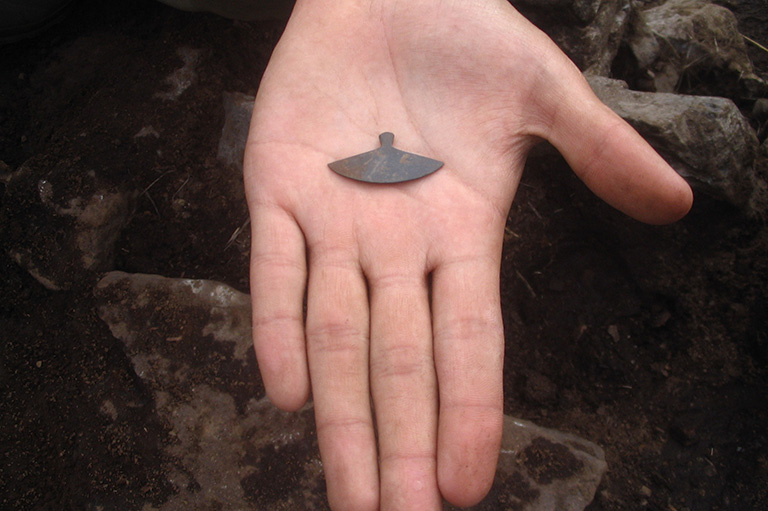

Excavating the 16th-century Nachvak location in 2003, Whitridge and his team found tools, knives and blades made from iron nails, but at Kongu the following year, they unearthed consumer goods, such as pottery, teacups, pipes and bottle glass.

Housing foundations at Kongu show a change to larger rectangular structures accommodating four or five families. Trade with Europeans played a much larger role in Inuit life.

Kongu’s location closer to the mouth of the fjord afforded greater opportunities for obtaining imported goods. They traded ivory, furs, oil, baleen and fish with Moravian missions and the Hudson’s Bay Company in exchange for firearms, tobacco, tea, sugar, flour and manufactured goods.

Later, with the end of whaling, a result of European overfishing, whale bone roof supports are not as common, replaced by wooden building materials.

During the late 1800s the sunken tunnel entrance is gradually replaced by a higher-roofed storm porch, and imported wood stoves are used for cooking, although the soapstone lamps remain.

Whitridge’s research also shows gradual change in gender relations, evidenced in the promotion of women’s spaces inside the home.

Men spent more time away from home, harvesting goods to satisfy the Inuit desire to trade for European goods.

Lampstands increase in number and move to more prominent spaces in the communal living area — a significant evolution, as the lamp represents a major symbol in Inuit life, providing light, warmth, cooked food, dry clothing and the soot used as pigment for traditional tattooing.

During the 19th century, says Whitridge, Labrador Inuit increasingly converted to Christianity. While many settled permanently around the Moravian missions, others, like the occupants of Kongu, refused to convert or resettle, actively resisting European influence.

Diseases such as measles and influenza took their toll, greatly reducing the population of Inuit communities. The influenza epidemic of 1918-1919 so decimated the population of Okak, the largest community on the north coast, that the settlement was abandoned.

As the area continues to be influenced by climate change, the Inuit continue to adapt. A large part of northern Labrador has been named the Torngat Mountains National Park Reserve, an area Whitridge says is on the verge of redevelopment as a cultural, adventure and ecotourism destination.

To learn more about the Moravians in Labrador and their influence on the Inuit, visit the Memorial University website.

At Canada’s History, we highlight our nation’s past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, while understanding that diverse past experiences can shape multiple perceptions of our history.

Canada’s History is a registered charity. Generous contributions from readers like you help us explore and celebrate Canada’s diverse stories and make them accessible to all through our free online content.

Please donate to Canada’s History today. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement