Roots: Your Name: A User’s Manual

We all have a right to a personal name, under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. The assignment of numbers, not names, is a predictable feature of any futuristic dystopia. Numbers are fixed, unchanging. Names are unpredictable, untamed — in short, human.

As a child, you learned from family and friends that personal names were malleable. An editor of this magazine reports that her mother has been known variously as Deirdre, Biddy, and Ann — all within her own household!

At some point before adulthood, you became aware that the naming conventions of your culture did not prevail everywhere. Many East Asian societies position personal names after family names (Hungarians, too), so we can hardly call them first names or forenames.

Where I grew up, we had Christian names. Today this terminology is best left to seminarians and historians. Some prefer given names, but is this description accurate when referring to authors, actors, or con artists who have chosen their personas? To be honest, I’m as likely as the next person to drop any of these terms into a casual conversation, although I do try to use the culturally neutral “personal name” when I’m paying attention.

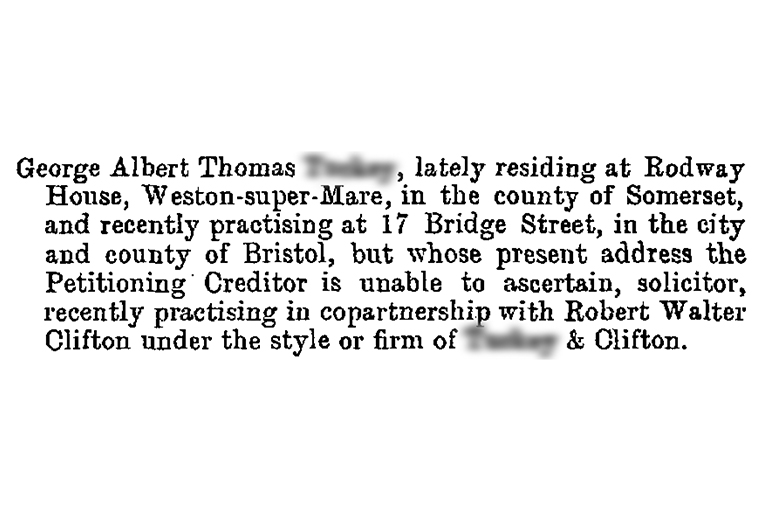

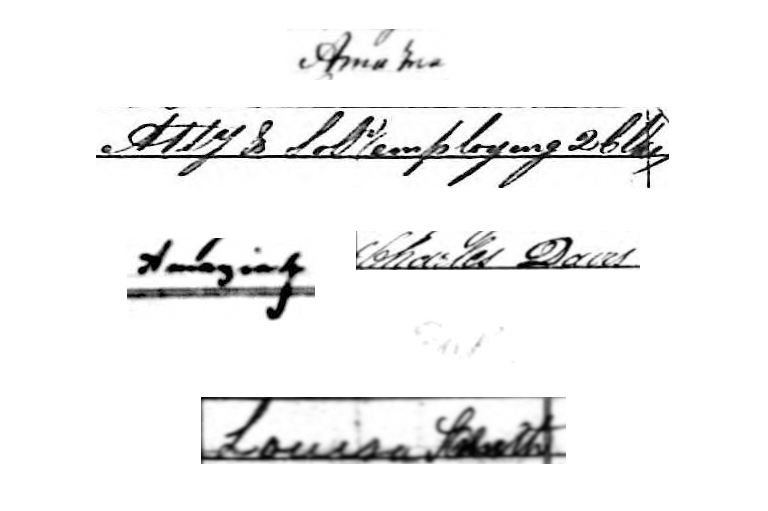

The reality is that semantic uncertainty is the least of the difficulties presented by personal names to family historians. The most common personal names often turn simple research problems into nightmares. Consider the case of a certain Mr. Gough. The proverbial needle in a haystack, he hid in plain sight in public records with two common names he used singly, together, and in any order — every permutation and combination of Thomas and John, including variations with initials. Scores of Gough men of the same age possessed one or both these forenames, and every appearance of any of them in the records might have been our man. Sorting out this mess took days.

I’m currently researching a Jewish man identified in Canadian immigration records as Solomon, a name that often gives rise to the nicknames Sol and Solly. If and when we find synagogue records, Solomon may well appear in the Hebrew alphabet in a form usually transliterated as Shlomo. When hanging out with his Yiddish-speaking friends and family, was he called Zalman or one of its variants or diminutives? These are all possibilities to bear in mind as we look at official and unofficial records of varying formality.

Fortunately, it’s not all hard work. Some personal names can be your research friend. For every John and Mary who’s a pain to identify with certainty, there’s a brother Victor or a sister Mildred who will be much easier to locate and to follow. In fact, when encountering a new family in your research, start with the individuals with the least-common names. By the time you’ve nailed them down, you’ll have a sense of the family’s structure and movements, which will make the Johns and Marys easier to find.

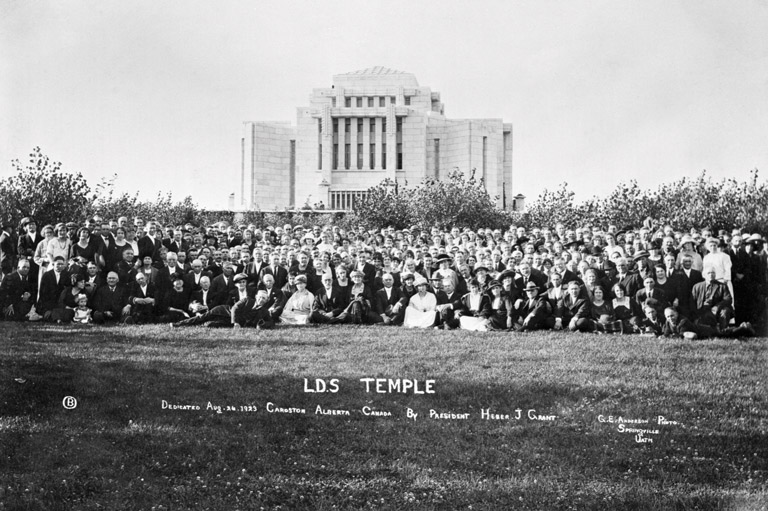

Familiarity with naming traditions can also help you to discover ancestors. If you come across a family of Scottish descent (something that’s hardly unknown in Canada), there’s a good chance that the eldest son was named after his paternal grandfather, the eldest daughter after her maternal grandmother, and so on. Of course, there were many exceptions, and naming patterns are not reliable as proof. But they can focus our efforts and reassure us that we’re on the right track.

Whenever you find someone with an unconventional middle name, you owe it to yourself to investigate. It’s often a homage to a godparent or to the mother’s birth family. The investigation of Eden Schüth Smith’s remarkable middle name absorbed my attention for months in 2022, eventually leading to research in six countries on three continents.

Above all, names are fun. We all have them, except reportedly the Indigenous Machiguenga people of Peru. For a really good laugh at “breathtakingly unlikelybut- true” names, I can warmly recommend Russell Ash’s 2008 compendium, Potty, Fartwell & Knob: Extraordinary But True Names of British People. Some of my favourites: Smallhope, Beasley, Mephibosheth, Lurid, Dust, Wanton, Moggy, and Errata.

Advertisement

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!