The Names and Knowledge Initiative

This year marks the one hundredth anniversary of The Beaver magazine. One of the enduring legacies of this publication is that it helped to create an extensive photographic documentation of Canada’s North.

Most of the photographs that appeared in The Beaver were part of the photography collection built by the Hudson’s Bay Company and kept at the Hudson’s Bay House Library in Winnipeg. These photographs were used to supplement the magazine’s articles and to provide visually appealing elements within the publication.

At their heart, the photographs serve as a record of how the HBC perceived its role and its relationships with the people and places in which it operated. Through the colonial lenses of the photographers, the HBC was able to publicize its interpretation of its role and romanticize its business activities and relationships with the people in the North.

This massive collection of over fifty thousand photographs, along with other records from The Beaver magazine and the Hudson’s Bay House Library, were part of the donation of HBC records to the province of Manitoba in 1994. They form the heart of the Hudson’s Bay Company Archives’ (HBCA) photographic holdings.

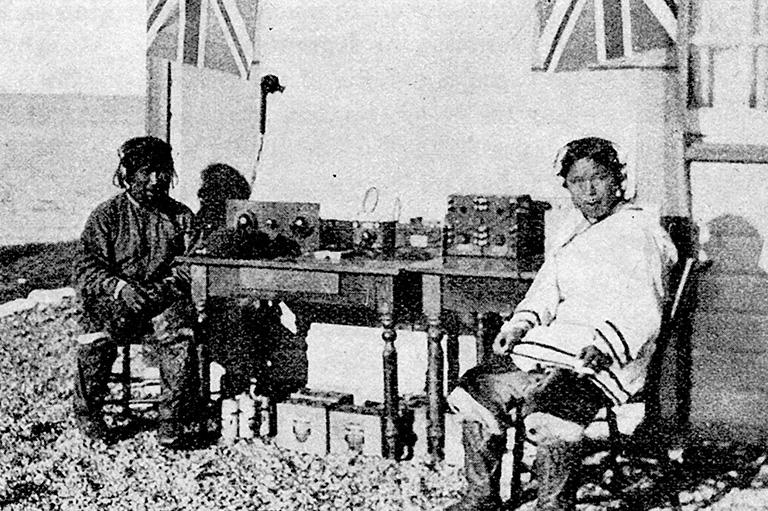

In many cases, there is extensive contextual information about these photographs. Many of them were captioned with detailed information about who was being photographed and what activities were being recorded. However, this contextual information is not always present. One of the obvious and unfortunate gaps in the contextual information is the many unidentified and misidentified Indigenous people seen in the photographs.

In October 2014, the HBCA established the Names and Knowledge Initiative. The goals of the project are twofold: to name unidentified or misidentified people and places in HBCA records and to make these records accessible to the individuals and communities the records are about.

In addition, the initiative also seeks the inclusion of knowledge from community members to provide a more holistic understanding of the records. As the majority of the unidentified photographs date from the 1930s to the 1970s, the realization that time was of the essence in sharing these images with Elders, who might also be the only people able to identify individuals in the photographs, further motivated this work.

When people are identified, or when additional knowledge about a photograph is shared, the information is included with the original caption in the Archives of Manitoba’s Keystone Database, along with the name of the person or people who provided it and/or their community name.

While original captions often contain outdated terms or incorrect information, it is important that they continue to be included with the photographs. Far from being discarded, this information provides evidence of not only the views and opinions of the creator but, oftentimes, society as a whole.

What photographers said about the images they created is as much a part of the archival record as the photographs themselves. The Names and Knowledge Initiative seeks to include Indigenous perspectives that were not seen as valuable or needed at the time the historic photographs in the Hudson’s Bay Company Archives were taken.

The Names and Knowledge Initiative has hosted several community naming events. The purpose of these events is to provide access to photographs in the communities in which they were created.

Individuals are encouraged to spend some time with the photographs, to provide identification, or to tell stories. These events are conversational and, sometimes, are as much about relationships as they are about the photographs themselves.

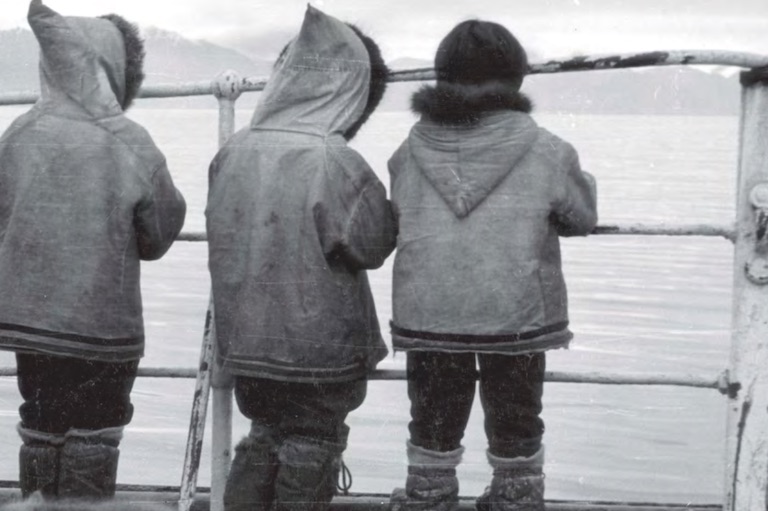

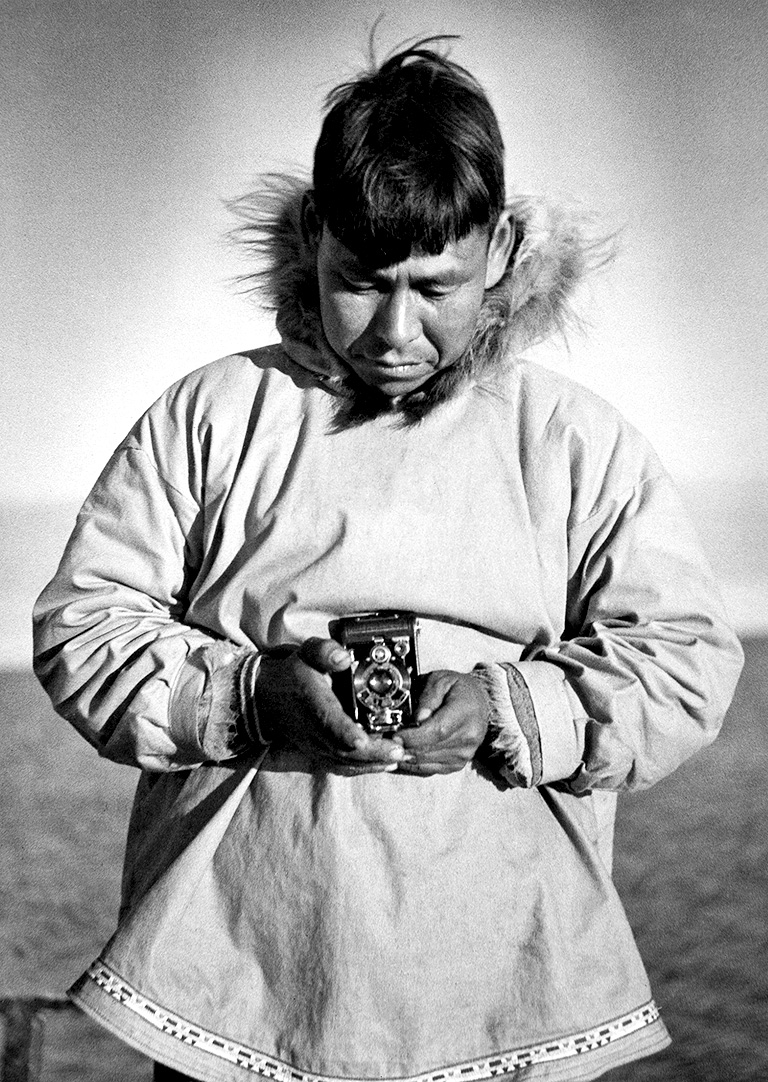

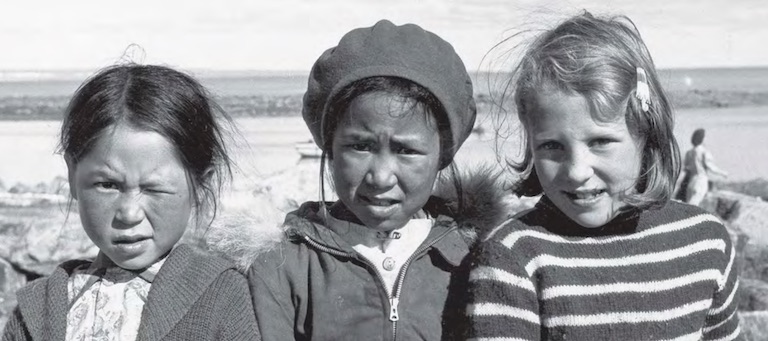

Naming events have resulted in the identification of numerous people portrayed in the photographs, including two images shown in this article, from which people were identified at an event held in Rankin Inlet, Nunavut, in 2015.

The images are strikingly beautiful portraits, but the descriptive information surrounding the photographs was very limited. One photograph (HBCA 1987/363-E-240/9) was taken by HBC store manager Albert Tessier and was simply captioned “Chesterfield.” Another photograph (HBCA 1987/363-E-210/12) was taken by O.J. Gromme and was captioned “Little Lily Swaffield and two of her native friends.” At the community naming event, the person in the “Chesterfield” photograph was identified as Suzanne Sammurtok. The Indigenous children in the second photograph were identified as Ayowna Emiktowt and Hattie Alagalak.

Another photograph (HBCA 1987/363-M-100/95), taken by Eddie Duck at Moose Factory, Ontario, was published in the Autumn 1973 issue of The Beaver with the caption “300th anniversary celebrations at Moose Factory, June 17, 1973. Members of the younger generation wait for the festivities to begin. An early fur press stands in front of the HBC store.” At a community naming event held in Moose Factory in 2017, all four people were identified: Vilmer Johnstone, Pauline Louttit, Jordanna Johnstone, and Andrew Johnstone.

Community participation in the Names and Knowledge Initiative has also made it possible for existing information to be corrected and for additional contextual information to be added to the photograph captions.

For example, a photograph of an Inuk woman (HBCA 1987/363-B-23/12) was originally identified as showing Sarah Empuk. A member of her community provided the proper spelling of her surname as “Ippak.”

The 1936 photograph of Bob Cockney (HBCA 1987/363-E-130/48) taken by Richard Hourde was enhanced by a family member with the provision of his Inuit name, Nuligak. An Elder from Pangnirtung identified the tent in the photograph taken by N. Ross (HBCA 1987/363-E-322/30) as Joanasie Kilabuk’s qarmuq.

Beyond the identification of individuals, photographs serve as a memory trigger and can be an excellent starting point for storytelling. A photograph simply captioned “Beluga processing for HBC at Pangnirtung” (HBCA 1987/363-E-347.1/11) was enhanced by a member of the community with a recollection of the events surrounding whale processing.

The Elder noted that, while others processed the whale for the HBC, Evie Anilniliak cared for the children. The same Elder added that Inuit workers were paid in store credit and could keep the non-choice parts of the whale to make soup.

Through community engagement and the building of relationships with individuals and organizations, hundreds of previously unnamed Indigenous people and places in archival photographs have now been identified.

Many images that were taken as part of HBC’s documentation of the North now include the names and knowledge of the Indigenous people who were previously considered to be only the subjects of the photographs.

Copies of these images, provided through the Names and Knowledge Initiative, are now part of family photo collections and are being used by Indigenous communities both as supplements to traditional education and in community exhibitions.

While to date photographs have been the focus of the initiative, the goal is to expand to records of all media, including maps and records kept at HBC posts and stores. The Hudson’s Bay Company Archives continues to seek opportunities to work with individuals and communities to provide access to records that record the history of Indigenous communities and to ensure that a representative and rich documentation is gathered and preserved for all who use the records, both now and in the future.

For more information on the Names and Knowledge Initiative, contact the Hudson’s Bay Company Archives at hbca@gov.mb.ca.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

100 Years with The Beaver

The Editor's Circle was founded in 2020 to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Canada’s History-The Beaver magazine. Gifts from patrons and supporters of $500 or more will be recognized annually.

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!