Sentinels of Sovereignty

In 1947, Minister of National Defence Brooke Claxton quietly announced the creation of an unorthodox military force: the Canadian Rangers.

Outfitted with armbands and bolt-action rifles, volunteers in remote areas of Canada were to provide a military presence on a shoestring budget. Sixty-six years later, the Rangers wear red sweatshirts and have access to more equipment, but they continue to thrive using the same no-frills approach, playing a prominent role in defence, nation-building, and stewardship.

Defence officials came up with the Ranger concept during the Second World War, when the Japanese threatened the West Coast. Terrified British Columbians pushed the federal government to improve coastal defences.

Evoking the mystique of untrained frontier fighters from centuries past, the army responded by forming the Pacific Coast Militia Rangers (PCMR) in early 1942. This temporary reserve force allowed British Columbian men who were too old or too young for overseas service, or engaged in essential industries such as fishing and mining, to contribute to home defence.

Apart from a sporting rifle, ammunition, an armband, and eventually a canvas uniform suited to the coastal climate, the army expected the Rangers to be self-sufficient. Using their local knowledge, they reported any suspicious vessels or activities they came across during their everyday lives.

If an enemy invaded, they were expected to help professional forces repel it. By 1943, there were nearly fifteen thousand Rangers representing all walks of B.C. life, from fish packers to cowboys. They trained with other military units, conducted search and rescue, and reported Japanese balloon bombs that landed along the coast.

The organization stood down when the war ended in the fall of 1945, having accomplished its home defence mission without firing a hostile shot.

A few years later, Canadians awoke to the reality of the Cold War. Realizing that the country did not have the resources to station large numbers of regular soldiers in its vast northern and remote regions, defence officials returned to the Ranger idea in 1947.

This time the force would spread across Canada. The first Ranger units took shape in the Yukon, then extended throughout the North and down the Atlantic and Pacific coasts.

The civilian backgrounds of these “ordinary” men (there is no record of any women Rangers until the late 1980s) determined their contributions, whether they were trappers, bush pilots, missionaries, fishermen, or miners.

In Indigenous communities, Inuit, First Nations, and Métis men filled the ranks — although until the 1970s the army usually appointed a token “white” officer to lead them. The Rangers’ local knowledge allowed them to serve as guides and scouts, report suspicious activities while going about their daily business, and — if the unthinkable came to pass — delay an enemy advance using guerrilla tactics.

The army equipped each Ranger with an obsolescent but reliable .303 Lee Enfield rifle left over from World War II (the type the Rangers still use today), two hundred rounds of ammunition annually, and an armband in lieu of a military uniform. Largely untrained, they were expected to hunt wildlife to hone their marksmanship skills.

The strength of the early organization peaked in December 1956, when 2,725 Rangers served in forty-two companies. Rangers filed reports on strange ships and aircraft and participated in training exercises with Canada’s Mobile Striking Force — a Cold War-era paratroop force designed to be flown quickly into remote northern areas.

In one case, Rangers even helped the RCMP intercept bandits trying to flee the Yukon along the Alaska Highway.

Journalist Robert Taylor observed that this diverse mix of Canadians was united in one task: “Guarding a country that doesn’t even know of their existence.”

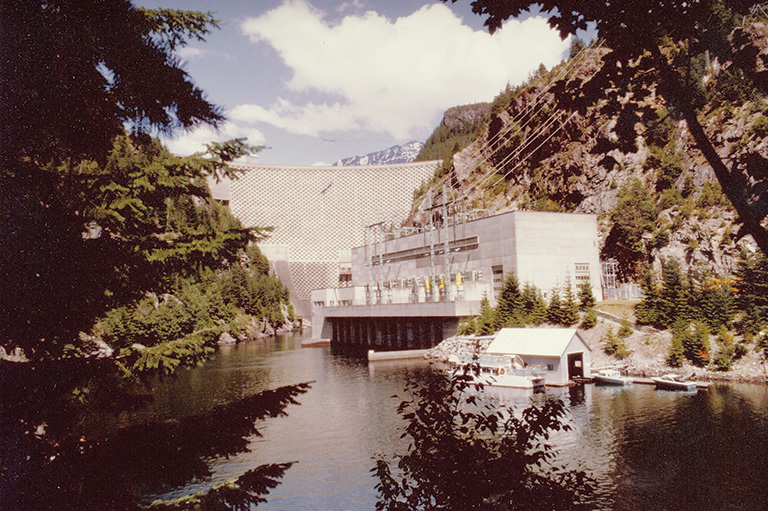

By the 1960s, Ottawa’s defence plans largely overlooked the Rangers. Citizen-soldiers with armbands and rifles could hardly fend off hostile Soviet bombers carrying nuclear weapons. Officials ignored the Rangers, turning instead to technological marvels like the Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line to protect the continent.

Apart from Newfoundland and Labrador, and a sprinkling of northern communities, the Canadian Rangers were largely inactive by 1970. That the organization survived at all was thanks to local initiative and its miniscule cost.

Then something happened to change the attitudes of defence planners: Humble Oil, an American consortium, sent the icebreaker Manhattan — a giant oil tanker — through the Northwest Passage twice in 1969 and 1970. The United States proclaimed that it did not need Canadian permission because the passage was an international strait.

All of a sudden, Canada’s hold over what it regarded as its Arctic was an issue. The government turned to the Canadian Forces to assert symbolic control, promising increased surveillance and more Arctic training for southern troops. Because the Rangers still existed — on paper, at least — and cost next to nothing, they fit the bill.

After the military established its new northern region headquarters in Yellowknife, staff travelled to communities to provide basic military training to Inuit and Dene Rangers. These meetings were very popular with the locals, who embraced the Rangers as a form of grassroots service.

Furthermore, northern Rangers patrols (as their communitybased units became known) now elected their own leaders — a unique form of self-governance. Revitalized by military support and respect, by the early 1980s the Rangers had resumed their roles as guides and expert teachers of survival skills in the Northwest Territories, northern Quebec, and along the eastern seaboard.

When the next Arctic sovereignty drama unfolded, the Rangers reached a new level of prominence. In 1985, the U.S. Coast Guard icebreaker Polar Sea pushed through the Northwest Passage without seeking Canada’s permission, resurrecting sovereignty anxieties.

The Conservative government of Brian Mulroney responded by promising big-ticket military investments to improve Canada’s control over the Arctic. At the same time, the Rangers received increased recognition and support. Media coverage began to emphasize the social and political benefits of the Rangers in Indigenous communities.

As a bridge between diverse cultures as well as between the civilian and military worlds, the Rangers successfully integrated national sovereignty and defence agendas with local interests. While most of the government’s promised investments in Arctic defence evaporated with the end of the Cold War, the Canadian Rangers increased in size in the 1990s. Most new growth was in Indigenous communities.

Journalists applauded the Rangers for teaching the military and for encouraging elders to share their traditional knowledge with younger people within Indigenous communities. The latter role led to the creation of a youth program, the Junior Canadian Rangers, in 1998.

By the twenty-first century, the Canadian Rangers had three broad tasks: conducting and supporting sovereignty operations; conducting and assisting with domestic military operations; and maintaining a Canadian Forces presence in local communities.

The Rangers have attracted their highest profile when patrolling the remotest reaches of the Arctic, showing the flag in some of the most challenging conditions imaginable. Since 2007, Rangers have participated in three major annual exercises: Nunalivut in the High Arctic, Nunakput in the Western Arctic, and Nanook in the Eastern Arctic.

The Rangers also conduct search and rescue operations and are the de facto leaders in their communities during states of emergency resulting from avalanches, extreme weather, forest fires, and other events.

The Rangers’ task of maintaining a military presence in local communities remains fundamental. As volunteers representing more than ninety percent of the Canadian Forces’ presence north of the 55th parallel, the Rangers play many local roles: providing honour guards for politicians and royalty visiting their communities, protecting trick-or-treaters from polar bears in Churchill, Manitoba, on Halloween, or blazing trails for the Yukon Quest and Hudson Bay Quest dog sled races.

Today there are nearly five thousand Rangers. With their distinctive red sweatshirts and ball caps, they are an appropriate form of military presence in remote regions. The southern establishment depends on them. Without access to local knowledge of the land, sea, and skies, southern visitors are hopelessly lost.

As Sergeant Simeonie Nalukturuk, a Ranger patrol commander in Inukjuak, put it, the Rangers are “the eyeglasses, hearing aids, and walking stick for the [Canadian Forces] in the North.”

The Rangers today are icons of Canadian sovereignty. They contribute to domestic security, make important contributions to their communities, and are stewards of our northland. Most importantly, their commitment does not fluctuate with the political winds of the south.

Facing an uncertain future, Canadians can rest assured that the men and women in red sweatshirts will remain vigilant as stalwart sentinels watching over their communities and the farthest reaches of our country.

At Canada’s History, we highlight our nation’s past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, while understanding that diverse past experiences can shape multiple perceptions of our history.

Canada’s History is a registered charity. Generous contributions from readers like you help us explore and celebrate Canada’s diverse stories and make them accessible to all through our free online content.

Please donate to Canada’s History today. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Sponsored by

This article, prepared for Canada’s History, is part of a four-part series on environmental history generously sponsored by the Walter & Duncan Gordon Foundation.

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Beautiful woven all-silk necktie — burgundy with small silver beaver images throughout. Made exclusively for Canada's History.