Agowigiiwinan Bezhig Minawaa Niizhin

In 2021 we commemorate one hundred and fifty years since First Nations peoples came together with the Crown’s representatives and entered into Treaty Number One and Treaty Number Two — agreements that, in the Ojibwe language, we call Agowigiiwinan Bezhig Minawaa Niizhin.

Some commemorative events were held locally in First Nations communities this summer, and others were held jointly among the historical Treaty partner representatives.

Who are the historical Treaty partner representatives? They are the First Nations peoples of this land — my relatives — and the Crown as represented by delegated government officials. They are the ones who set the Treaty table, came together with a vision for each of their peoples, and within that spirit and intent made a solemn agreement as to how we would live together in peace and share in the bounty of the land. It is now 2021, one hundred and fifty years later. We get to reflect on their legacy and to take stock of what we have done with that vision and of the ties that connect us all as Treaty people.

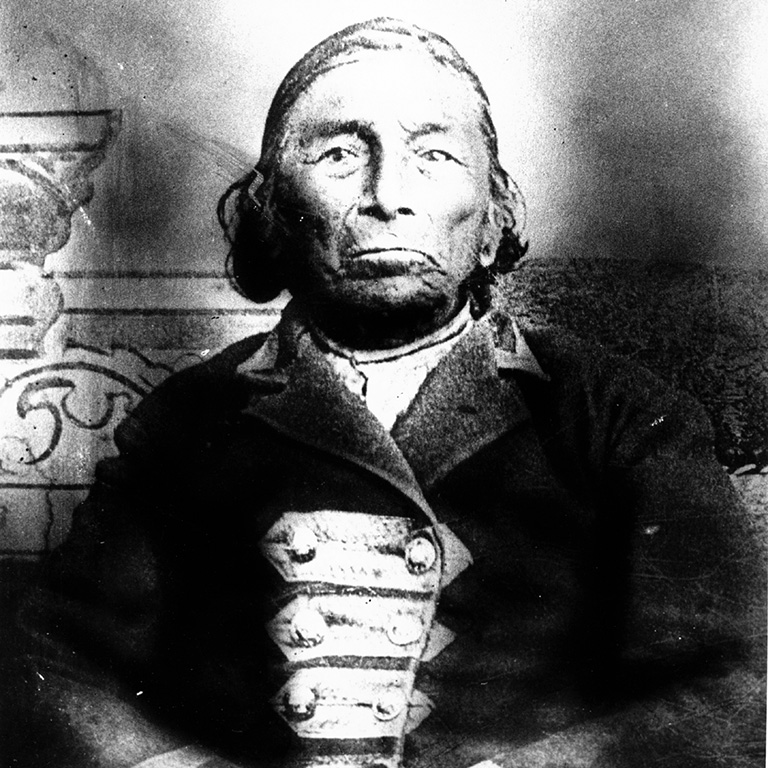

My personal connection to Treaty One is through my great-great-grandfather William Asham, on my paternal grandmother’s side. He was a young man of eighteen years when he witnessed the making of Treaty One at the Stone Fort (Lower Fort Garry, Manitoba). I am also a member of the Peguis First Nation, one of the signatories to Treaty One. The Treaty legacy is dear to my heart. As a Treaty person, I take my responsibility seriously to uphold the Treaty and to honour the vision our leaders had for us: to ensure that we retained our way of life and the relationship with our lands. Much has happened since 1871 to dispossess First Nations people of our lands, languages, and way of life. Today we are fortunate that there are opportunities available to us to learn our languages and to connect with our way of life, thanks to those who preserved the languages and the ways of our people and who made a lifetime commitment to teaching others. Kinanaskomitin. Miigwech. Thank you to our relatives.

Sanitizing the story is not helpful. Searching for truth is honourable and requires an ethical historical-thinking lens and respect for the nation-to-nation relationship.

Treaty One was formalized on August 3, 1871. Treaty Two was formalized eighteen days later on August 21. However, to fully understand the Treaties, we must think about all of the talks that led up to 1871, as well as the subsequent events that have occurred up to the present day. This includes the oral tradition, the written words, and our efforts to find truth in that balance. It is about our relationship to the land and the original spirit and intent of the Treaties that included sharing the land and resources so that all peoples could enjoy its benefits. It is about seeking understanding of what has happened since the historical Treaty partners set the Treaty table and reflecting on the responsibility we each carry for upholding the Treaties. It is about reconciliation and having hope for the future.

We also need to consider the Outside Promises of Treaties One and Two — commitments that were made by Crown negotiators but that were not included in the written Treaty documents. The Outside Promises were eventually addressed in 1875 with a memorandum added to Treaties One and Two; however, they were open to interpretation and did not include everything that First Nations had understood to be part of the Treaty agreements.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

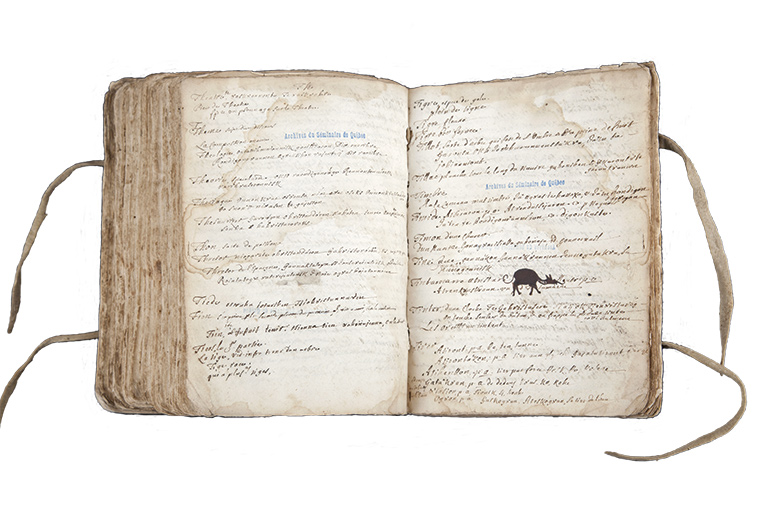

There are two Treaty stories, or narrative histories, that we must now strive to reconcile. One is the story told by First Nations’ oral history. The second is the written story told in primary documents such as the Treaty documents themselves, along with petitions written by First Nations leaders and journals, letters, and newspaper articles written by Canadian officials and others who were present at the Treaty talks. Today we also include secondary sources such as publications by scholars and researchers to help us understand the full story of Treaties One and Two. I hope that the emerging narrative will help us to move closer to a balanced version of what transpired at the Treaty talks and to understand the subsequent implementation and honouring of the promises that were made. Sanitizing the story is not helpful. Looking for truth is honourable and requires an ethical historical-thinking lens and respect for the nation-to-nation relationship.

The need for Treaty One arose from two different sets of circumstances. By the mid-1800s, First Nations leaders in the area now encompassing Manitoba and Saskatchewan had become anxious to conclude a Treaty with immigrant settler government representatives in the region. An earlier Treaty, negotiated between First Nations people and the Scottish earl and Hudson’s Bay Company shareholder Lord Selkirk, had allocated land along the Red and Assiniboine rivers in present-day Manitoba to enable the founding of a community of Scottish immigrants. The Peguis-Selkirk Treaty of 1817 was supposed to have been concluded upon Lord Selkirk’s return from Britain to pay the rent to the First Nations signatories. However, Lord Selkirk died in 1820, and the Treaty rents were never paid.

In the ensuing years, the growing community of immigrant settlers at the Red River Colony continually encroached on land outside of the Treaty allotment.

This prompted First Nations leaders to petition the British Crown to complete the unfinished business of the 1817 Treaty.

By the 1870s, First Nations in the West were growing increasingly concerned about the colonization that was sweeping over the land, bringing with it a new way of thinking, a new way of relating to the land and life upon it, and a new way of living. The land was being altered to make room for immigrant settlement, development, and new economies.

Surveys parcelled out pieces of land for individual ownership. New foreign place names replaced original place names.

Permanent structures emerged, and new government buildings began to overshadow the historical forts and early trading posts. These tremendous changes exponentially impacted First Nations’ ways of life and relationship to the land and all it provided.

It became increasingly evident to First Nations people that a Treaty was needed in order to ensure that First Nations’ ways of life were protected. Such a Treaty needed to outline how the Treaty partners were to relate to one another and share the land. First Nations diplomacy via Treaty-making had worked in the past. First Nations leaders anticipated that this process would also apply to what would become Treaties One and Two.

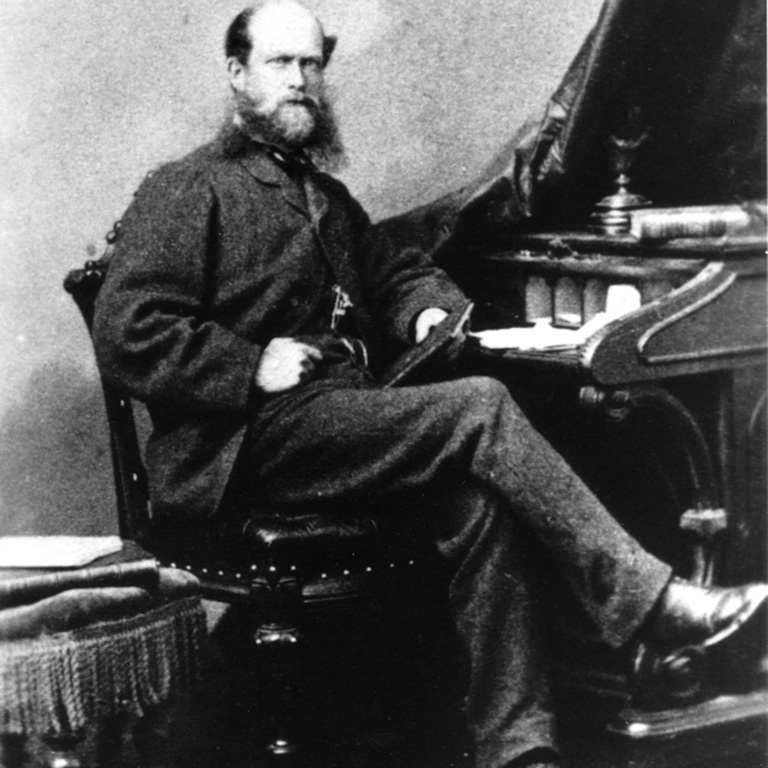

Meanwhile, the British Crown had an interest in further developing the Dominion of Canada, which had been created in 1867. Concerned that the United States would attempt to annex the area that today comprises the Canadian Prairie provinces, the British and Canadian governments wanted to expedite the linking of the new Dominion in the east with the colony of British Columbia on the west coast.

In March 1869, the Hudson’s Bay Company sold the vast northwestern territory known as Rupert’s Land to Canada. The sale — made without consulting the First Nations or Métis peoples of the region — sparked the Red River Resistance led by Métis leader Louis Riel that ultimately helped to create the province of Manitoba in 1870.

With the Dominion of Canada now eyeing millions of hectares of land in the west for potential settlement and development, the need for Treaties was clear: There were matters to be settled that had not been dealt with in proper negotiations with the First Nations peoples. There had been no Treaty made covering the vastness of the former Rupert’s Land and the Northwest Territories, nor for the millions of hectares further west that were being surveyed by the federal government. The need for reconciliation was already on the horizon, as the manner in which these lands were obtained was in question.

THE NUMBERED TREATIES

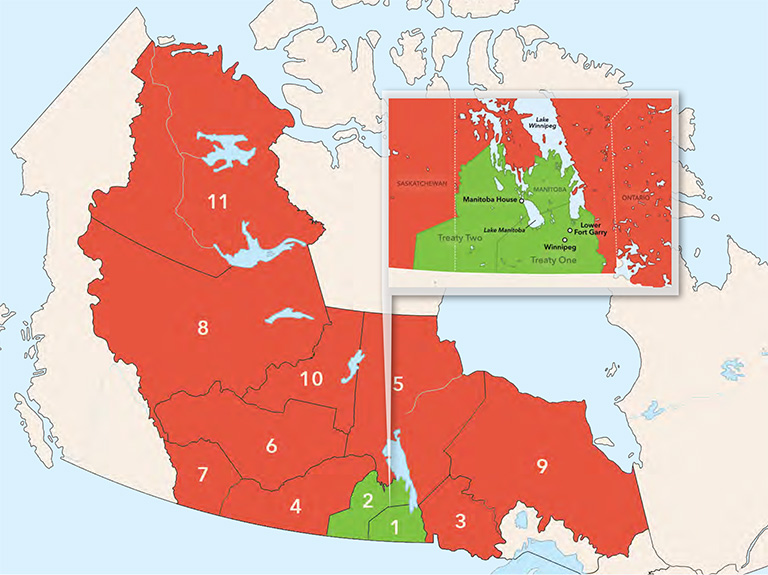

Treaty One and Treaty Two are the first of eleven numbered Treaties that represent the source of the unique nation-to-nation relationship between the Crown and the First Nations peoples living within a vast crescent of land that stretches from James Bay in the east to the Rocky Mountains in the west, from the forty-ninth parallel in the south to the Arctic Ocean in the north.

Treaty One relates to the land and peoples within an area of approximately eighteen thousand square kilometres to the south and southwest of Lake Winnipeg and Lake Manitoba.

Treaty Two covers an area of approximately eighty-seven thousand square kilometres directly to the north and west of Treaty One territory.

The oral tradition states that the Treaties were seen as reiterating peaceful alliances, securing assurances for both parties to share the wealth associated with First Nations’ ancestral lands, and ensuring the respectful right for each party to retain its own way of life.

The written preamble to Treaties One and Two states that the purpose of the Treaty negotiations was “to deliberate upon certain matters of interest” to both the British Crown and the First Nations peoples.

It was “the desire of Her Majesty [Queen Victoria] to open up to settlement and immigration a tract of country ... and to obtain the consent thereto of her [Indigenous] subjects inhabiting the said tract, and to make a treaty and arrangements with them so that there may be peace and good will between them and Her Majesty.”

To address these long-standing matters concerning land, several petitions from First Nations leadership had been sent to different bodies. Among those petitioned were the Aborigines Protection Society in Great Britain (1859), the Nor’Wester newspaper in Winnipeg (1869), and Adams Archibald, Lieutenant-Governor of Manitoba (1870). The First Nations leaders urgently requested advocacy for a Treaty to address the matter of immigrant settler encroachment.

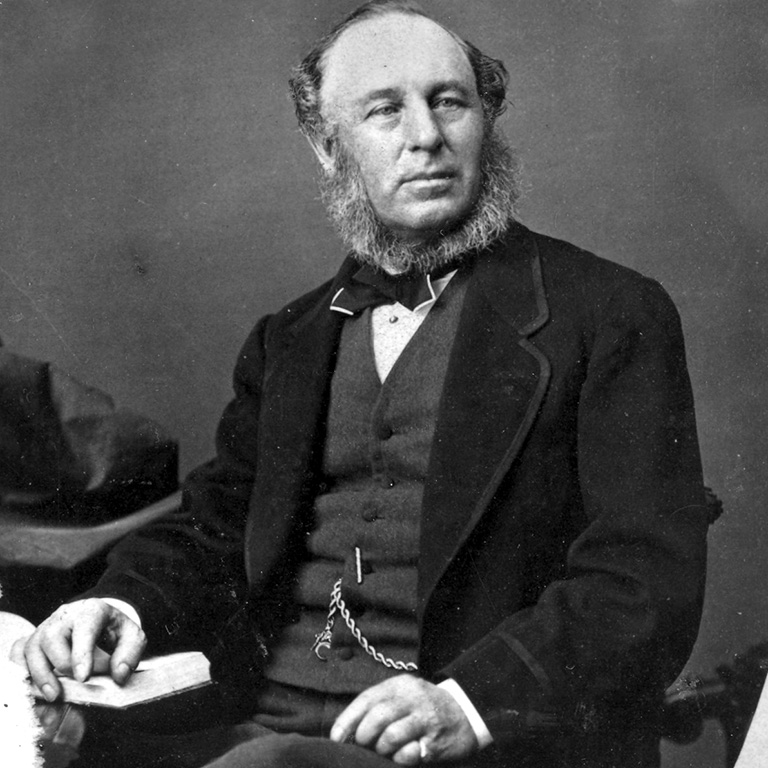

It was within this buildup of circumstances that First Nations leaders and Crown representatives agreed to come together in Manitoba in July 1871 to make a Treaty. Canada provided an Order-in-Council for a Treaty commissioner, enlisted the support of representatives from the province of Manitoba, and, through royal proclamation protocol, posted notice to First Nations that Treaty talks could begin in July 1871. Once there was agreement to begin Treaty talks, the First Nations and the Crown began their preparations.

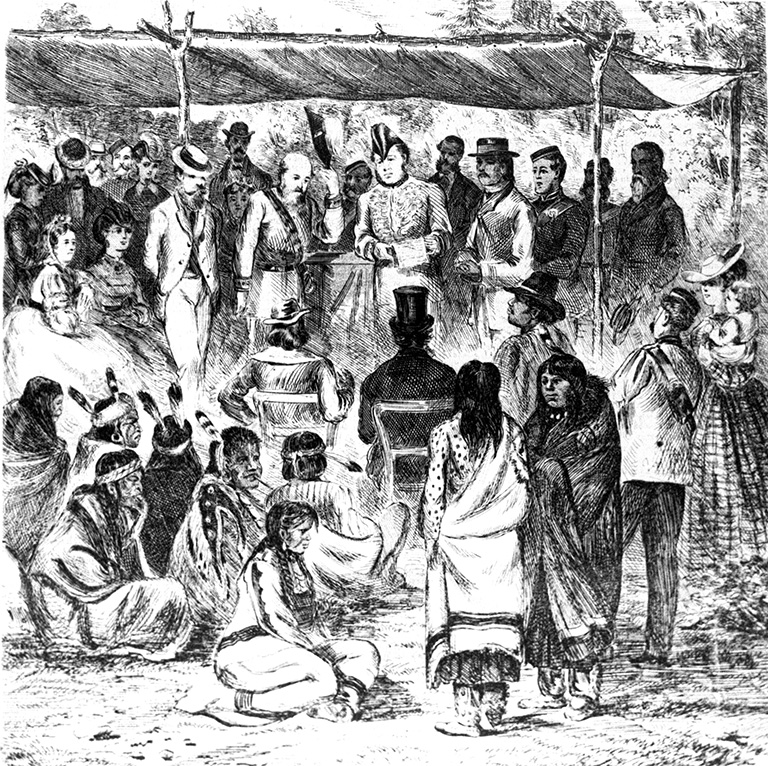

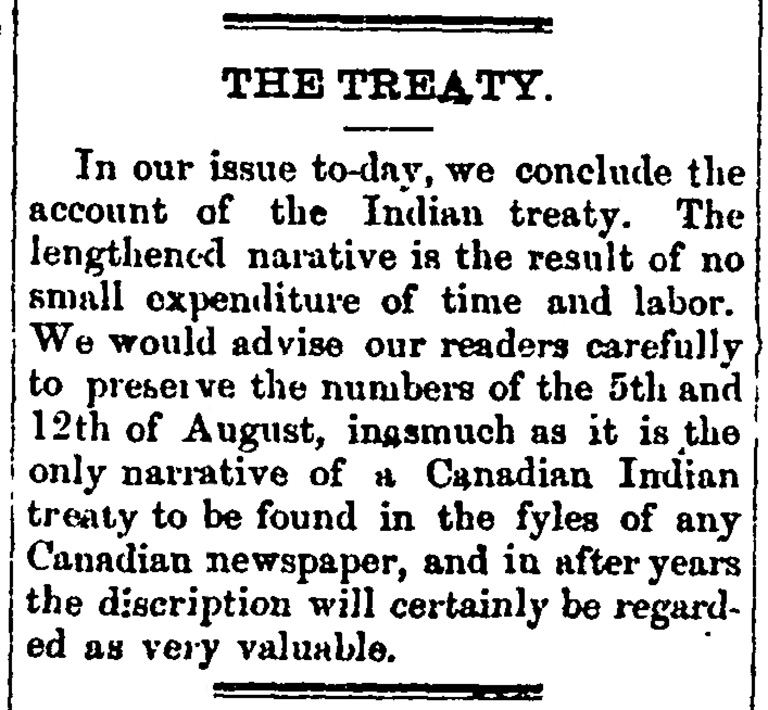

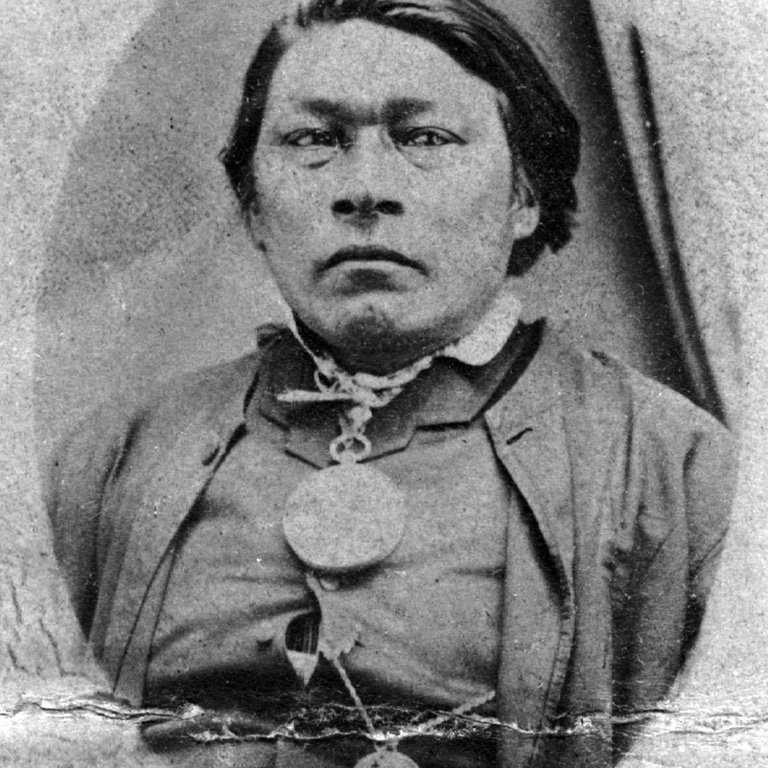

The gathering of more than a thousand First Nations people at the Stone Fort at Lower Fort Garry was a sensation for the media. First Nations people travelled from their southern, southwestern, and southeastern ancestral lands to witness the talks. The Manitoban newspaper, which covered the Treaty negotiations, remains a source for details that are not included in the Treaty text or in government correspondences on the Treaty talks. The daily reports provide some insight as to what both parties were proposing and how the terms of the Treaty were agreed upon. For example, on the last day of the Treaty talks, the Manitoban recorded Chief Henry Prince, whose father Chief Peguis had participated in the making of the Peguis-Selkirk Treaty, as saying, “The land cannot speak for itself. We have to speak for it.” His words expressed the spiritual connection of First Nations peoples to the land and the responsibilities associated with that relationship. This relationship was not relinquished through Treaty.

After eight days, these talks concluded on August 3 with the Treaty One agreement outlining the solemn promises made by the two historic Treaty partners. At the same time, some Chiefs at the Stone Fort gathering made it known that they wanted to have a Treaty concluded closer to their home territories. This resulted in Treaty Two, which was signed on August 21 at the HBC trading post at Manitoba House on the west side of Lake Manitoba.

DIFFERING INTERPRETATIONS OF THE TREATIES

In her book Breathing Life into the Stone Fort Treaty, Indigenous lawyer Aimée Craft explains that, even during the negotiations, settlers (represented by Crown negotiators) and First Nations people (represented by their Chiefs) had fundamentally different interpretations of Treaties One and Two.

Craft explains that First Nations people understood the Treaties in the context of previous trade Treaties concluded with the Hudson’s Bay Company, as well as Treaties settled amongst First Nations themselves.

These Treaties did not entail giving up land or sovereignty but rather laid out agreements on how to share the land and its resources.

Treaties often relied upon ties of kinship — such as marriage and adoption — to forge bonds among nations.

In seeking to interpret Treaty, Craft points out that ceremony, symbolism, verbal promises, and objects such as peace pipes and wampum belts carried the same weight for the First Nations signatories as the written Treaty documents did for the Crown negotiators.

Treaties One and Two described in geographical terms the ancestral lands of each signatory First Nation and allocated a certain amount of land within each of those territories as “Indian Reserves,” in the amount of 160 acres (64.7 hectares) per family of five.

Yearly payments from the Crown to each family were defined.

Verbal assurances were made during the Treaty negotiations that First Nations people could continue to practise traditional pursuits, including hunting and fishing, in their ancestral lands.

Throughout the negotiations, the Crown negotiators referred to Queen Victoria as “the Great Mother” to the First Nations people, invoking ties of kinship and a duty of care.

Relying exclusively on the written Treaty documents, Canadian governments have interpreted the Treaties to mean that First Nations people “[did] cede, release and surrender” all of their land except the “Indian Reserves” to the Crown.

Craft explains that First Nations people did not, and do not, share that interpretation. From the First Nations’ perspective, the Treaties are nation-to-nation agreements laying out how to share the land and its bounty.

Within a year of the conclusion of the Treaties, First Nations leaders began to raise the issue of the Outside Promises. The First Nations signatories to Treaties One and Two had been verbally promised additional goods, farm implements, and livestock to be provided yearly.

However, it would take until 1875, during the making of Treaty Five, for these concerns to be addressed. Additional matters remained outstanding that later came to be part of what is called a Treaty land entitlement process — a process of redress for First Nations that did not receive all the land to which they were entitled under Treaties made by the Crown. These discussions continue to the present day.

The path to 2021 has not always honoured the original Treaty intentions and promises. The immigrant settlers’ version of history has been shared many times over, primarily based on the collection of written documents. It is only recently that the oral tradition has been considered a source of evidence.

This has brought a more balanced perspective to the Treaty story. After many years of challenges and struggles, the Treaty-making process is now being seen through a lens of reconciliation. However, recent events concerning the discovery of unmarked graves of First Nations children who attended residential schools are challenging reconciliation efforts.

This discovery is directly tied to the Crown’s unilateral interpretation of First Nations’ children’s right to education, which was embedded in the Treaty text: “Her Majesty agrees to maintain a school on each reserve hereby made whenever the Indians of the reserve should desire it.” The impacts of the creation of the residential school system will continue into the future, as the harsh truth of the residential school experience is further exposed and as Canadians continue to grapple with the one-sided historical narrative they have been taught.

Prior to the discovery of the unmarked children’s graves at residential schools across the country, including in Manitoba, there have been acts of reconciliation occurring in Treaty One territory.

These include a recent revamping of how the Manitoba Museum has portrayed Indigenous peoples, as well as an invitation for Indigenous people to participate in the sharing and presentation of the story of Treaty in Manitoba. This has included ceremony, such as an annual smoking and feasting of the pipes.

COMMEMORATING THE TREATIES

The commemorative events for the anniversaries of Treaties One and Two required flexible planning this year, due to the global COVID-19 pandemic. Some events were planned locally in First Nations communities, while others were organized jointly among the historic Treaty partner representatives.

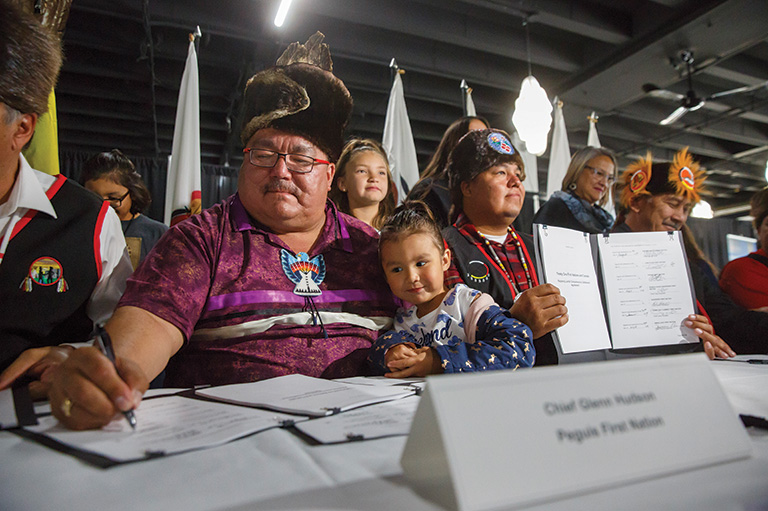

On August 3, representatives of the Treaty Relations Commission of Manitoba and of the Treaty One Nation (which includes all seven First Nations signatories to Treaty One) gathered with Canadian and Manitoba government officials for a commemorative event at Lower Fort Garry National Historic Site (also known as the Stone Fort).

The event began with a pipe ceremony and a drum song, followed by a formal flag-raising ceremony. Each flag was lowered to half-mast in memory of the Indigenous children who died in residential schools. Indigenous horse riders Oyaate Techa conducted an Honour Ride.

“We are not only celebrating the hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the signing of Treaty One in 1871, we are also renewing and affirming the Treaty relationship that is a central building block of Confederation,” Grand Chief Arlen Dumas of the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs said in a speech during the event.

Dennis Meeches, the Chief of Long Plain First Nation, told the CBC: “The Treaty hasn’t always been good to or kind to Indigenous people, as what it should have been intended when our ancestors signed this Treaty. They believed they’d have true partnership, true sovereignty. A sovereign nation within a sovereign state. All that was basically thrown out the door before the ink was even dry.”

Loretta Ross, Treaty Commissioner for the Treaty Relations Commission of Manitoba, presented new Treaty medals to representatives of each Treaty One First Nation. Various Treaty Two nations planned commemoration events, each reiterating the sovereign nation-to-nation relationship that resulted in the making of Treaty Two.

Amid the commemorations, questions persist — questions such as: Why is Treaty Two not being commemorated at the same level as Treaty One? Why hasn’t Manitoba House become a historical site of significance? These are legitimate inquiries. Perhaps this article will give context to some of the questions being posed.

— Wabi Benais Mistatim Equay (Cynthia Bird)

At The Forks National Historic Site at the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine rivers in Winnipeg, visitors can view art installations that tell the traditional stories of the people and the land. These artworks, along with the building of a traditional lodge at Niizhozii-bean (the south point of The Forks), are examples of reconciliation and the acknowledgement of First Nations’ centuries-long spiritual connection to this location. The lodge represents a place for all to gather in the spirit of reconciliation. It is a meeting place for sharing, teachings, ceremony, celebration, and healing.

Treaty Two First Nations have also been promoting acts of reconciliation. They are making lodge teachings available, renewing Treaty relationships with non-Indigenous residents of nearby towns, and assisting others in understanding the importance of land acknowledgements.

What is important about these examples is that the dialogue is becoming more open and the narrative is becoming more balanced — especially as Canadian society begins to realize that the work needs to be collaborative, not unilateral.

Across the country, governments and Canadians in general are growing more aware that there are other ways of thinking and of doing. They are acknowledging and understanding that First Nations peoples have been part of the past, are very much present, and will continue to be here in the future. Going forward, respect for the nation-to-nation relationship and consistency in words and actions remain important foundational approaches to the Treaty relationship renewal process.

Treaties remain relevant to Canadians’ shared past, present, and future. One hundred and fifty years following the making of the first of the Numbered Treaties in 1871, First Nations people continue to assert our sovereignty in the practice of the pipe ceremony and in using our original languages, customs, and traditions to honour the original spirit and intent of Treaty. First Nations continue to pursue every opportunity to connect with our ancestral lands, as evidenced in the Treaty land entitlement processes that serve to rectify the original Treaty land allocations. When this is done, it can present tremendous economic opportunities for Treaty nations, as was envisioned by the leaders who signed the 1871 Treaties. For instance, in Winnipeg Treaty One nations have worked with federal and local governments to complete the transfer of the land that once was home to the Canadian Forces’ Kapyong Barracks.

First Nations’ relationship to this land was formed long before the arrival of European traders and immigrant settlers. Through Treaty the land became part of Treaty One territory and was eventually absorbed into the city of Winnipeg. Over time it has been designated by various names: Winnipeg, River Heights, Crown land, Kapyong Barracks. In 2019, it finally reverted back to being First Nations land. It now has a new name, Naawi-Oodena, meaning “centre of the heart and community.” Two thirds of the sixty-eight-hectare site have been designated as an urban reserve (also known as a First Nations economic zone) and are being redeveloped for residential, commercial, and recreational uses by the Treaty One Development Corporation. Directors of the corporation are the Chiefs of the seven First Nations that are signatories to Treaty One. It holds a bright future.

Much reconciliation work remains. It is a new path that must be understood in the context of colonization and in the spirit and intent of the historic Treaties that helped to build this country. It can be an exciting journey that will help all Canadians move closer to accepting new ways of being and knowing. Public education for all Canadians, including government leaders across jurisdictions, remains a fundamental vehicle for supporting these conversations, discussions, negotiations, and deliberations.

The commemorative events for the 150th anniversaries of Treaties One and Two provided experiential learning opportunities for all people. After all, we have all benefited from Treaty — whether we want to understand it or not — and future generations will also benefit. We are all Treaty people. We have a responsibility to understand what this means and how it translates into a personal responsibility to uphold the original spirit and intent of the Treaties.

Let us work together to realize the respectful relationship our ancestors envisioned when they sat at the Treaty table to talk about how we all can honour our relationship to the land and live in peace.

The commemoration of Treaties One and Two is about reconciling our relationship to the land we live on and all that has happened on it since 1871. It provides an opportunity to look inward to see how we have been relating to one another over the last 150 years and to ask ourselves: How can I make this better for our children and grandchildren so they can be free to be who they are and live in peace?

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

The Editor's Circle was founded in 2020 to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Canada’s History-The Beaver magazine. Gifts from patrons and supporters of $500 or more will be recognized annually.

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!