Watershed Moments

Around midnight on May 5, 1950, Manitoba Premier Douglas Lloyd Campbell summoned Winnipeg’s veteran city engineer, William D. Hurst, to an emergency meeting. Hurst arrived to find the premier huddled with senior military officers, including the head of the Canadian Army’s Prairie command.

A rural politician with strong ties to Manitoba’s frugal farming communities, Campbell informed Hurst that the federal government had approved the use of the army, navy and air force to confront a rapidly encroaching disaster. For two weeks, a major flood had been spreading across southern Manitoba, caused by a heavy spring melt that ran north from the Dakotas and collided with the ice floes on the Red River. As the northbound water spilled over the riverbanks, Winnipeg found itself on the verge of being swamped.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Winnipeggers were well accustomed to flooding along the Red River, especially at its confluence with the Assiniboine River. But nothing of this scale had occurred since the 1860s. Hurst, who had been warning the premier for days about the risk, reckoned he’d need thousands of volunteers to fill and place sandbags to shore up the dikes that crisscrossed the city.

A few hours later, Hurst briefed the members of city council, stressing public-health dangers such as the soon-to-be-inundated sewer system. Campbell had already declared a state of emergency, so city council put Hurst in charge of a committee of top civil servants tasked with confronting the crisis, including the chief of police and the medical officer of health. The committee was told to spend whatever was necessary to confront the disaster and coordinate with relief agencies. Leaving that session, Hurst’s team set up a war room in the city engineer’s office. The first order of business: fitting out the space with telephones and operators to field the thousands of calls pouring in from panicky Winnipeggers who were watching as their neighbourhood streets and homes disappeared beneath the cresting river.

Destructive floods have become a hallmark of climate change — the consequence of sea level rise, hurricanes and unpredictable temperature fluctuations. Their contemporary scale and frequency mean such events have become more destructive due to urbanization, especially in such low-lying areas as Winnipeg’s Forks or Calgary’s Bow and Elbow rivers. Anthropologists and historians have found that the memory of flood disasters linger within communities for generations — a testament to the devastation that occurs when fast-moving waters wash away buildings, people and infrastructure with fearsome effortlessness.

There are other repercussions: Hurricanes Katrina (2005) and Sandy (2012) exposed political neglect in New Orleans and New York City, respectively. In the 1950s, after violent North Sea gales caused tremendous flooding in the Thames Estuary and throughout the low-lying regions along the Netherlands’ western coast, both Great Britain and the Netherlands constructed herculean flood-protection works — dams, dikes, polders, floodgates and protected flood plains — to prevent future catastrophes.

Canadian history is replete with dramatic floods, from the 1826 flood of the Red River Valley to flash summer storms in downtown Toronto in the early 2020s that swamped commuter trains and underground parking garages. The iconic 1996 photograph of a house stranded in the middle of a surging spillway below overtopped dams on the Chicoutimi River, in Quebec’s Saguenay region, came to symbolize an epic flood that displaced 16,000 people, heavily damaged 7,000 homes and left 10 dead.

Yet, four major mid-20th-century flood events — Halifax in 1942; the Lower Fraser River in 1948; Winnipeg in 1950; and Toronto during Hurricane Hazel in 1954 — stand out, not just for their ferocity but also for the long-term impact of the ensuing response.

Advertisement

Wildwood Park is a leafy master-planned neighbourhood, developed in 1946-47 on a kidney-shaped peninsula nestled in a bend of the Red River, a few kilometres south of the Forks.

The river was washing over Wildwood at about the time Hurst had gone to meet with Manitoba’s premier. “Wildwood evacuated on ten minutes’ notice,” local journalist Vinia Hoogstraten wrote in the August 1950 issue of Chatelaine. “Somewhere between five and ten percent got their furniture out. The rest made impromptu trestles and put their things up as far as they could.” Dozens of local men tried in vain to patch the breached dike with mud. Others found small boats and paddled from house to house, offering to save furniture and store it in a nearby warehouse.

Over the next several days, Hoogstraten visited numerous homes and spoke with the benumbed owners. Their houses, stinking of mould and rot, had mud-caked floors and were strewn with broken furniture. Many neighbourhoods remained submerged under as much as 4.5 metres of water for 51 days.

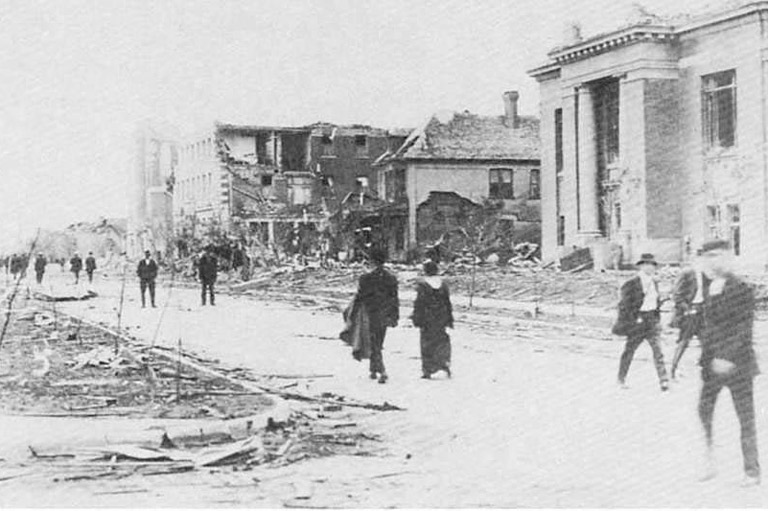

Once the waters receded, officials reported that about 100,000 people had been evacuated, 10,000 homes were destroyed and 5,000 other buildings were damaged. The bill exceeded $125 million, about a billion dollars today.

Manitoba’s political culture had long been dominated by small government fiscal conservatives who balked at such expenditures, explains historian Gerald Friesen, a professor emeritus at the University of Manitoba. “Pragmatic, business-oriented, unambitious, not entrepreneurial,” as he says. Premier Campbell didn’t want to spend any more than he had to on the aftermath of the Red River flood. But with shocking newsreel footage of the disaster playing in theatres across North America, donations poured in. Campbell calculated that Ottawa would offer up relief funds, which ultimately got him off the hook for more than half the cost. (While there was no national disaster program at the time, Ottawa had covered 75 per cent of the remediation cost of the Fraser River flood of 1948, and thus, a precedent had been set.)

“[Campbell’s] response to the Manitoba Flood of 1950 was cautious and heavily criticized at the time for its failure to act in advance of federal assistance and its unwillingness to insist on more support from Ottawa,” writes historian J.M. Bumsted in an academic paper about the disaster. “Campbell always insisted that he had not wanted to act without Dominion [federal government] assistance, and that he had done what he could.”

Despite millions of dollars in emergency relief, Campbell continued to face heavy pressure from critics and city dwellers who felt he hadn’t responded quickly enough in the days before the city was overwhelmed. Greater Winnipeg works officials, using federal funding, set out to build higher berms around the edge of the city, as well as additional pumping stations.

Some experts, however, didn’t think such measures were sufficient. In 1953, the federal government published its own response. They urged the province to construct a floodway designed to divert high waters flowing through the Red River Valley toward Winnipeg into a 48-kilometre-long ditch. It would circumnavigate the city and reconnect with the Red downstream, shunting flood waters into Lake Winnipeg.

During high-water periods, immense control gates in the bed of the river would be raised, redirecting the flow into the ditch. It was a bold and expensive idea — the sort of infrastructure megaproject that Manitoba had never seen before. The floodway, says Friesen, “was going to cost $50-$100 million, which was a lot of money in those days, especially to Campbell, and he didn’t want to spend it.”

The premier’s stall tactic was to empanel a royal commission, which he hoped would determine that the floodway would be too expensive to justify.

In December 1958, the commission released its recommendations: the construction of a floodway around Winnipeg, a storage reservoir west of the city and a diversion channel for the Assiniboine River. Taken together, they would protect the city against a 160-year flood. With the St. Lawrence Seaway less than a year from completion, the commission’s proposal reflected the temper of the times: the construction of muscular engineering projects meant to tame nature for the public good.

The prospect of building a big-dollar project that wouldn’t benefit his rural base exacted a political toll on Campbell, who’d let it be known he wasn’t interested in financing a floodway even before the commission finished its work. In the late-spring election in 1958, he was challenged by, and lost to, Duff Roblin, a Winnipeg businessman who ran on a promise to construct the floodway. The collective memory of the 1950 flood’s devastation was still very much alive among voters. “This particular flood did not die,” says Friesen. “People have been aware ever since that Winnipeg is in a difficult situation.”

When it was finished in 1968, the floodway (dubbed “Duff’s Ditch”) cost $63 million. According to a Manitoba government fact sheet, the project was the world’s second-largest excavation initiative, after only the Panama Canal.

While it would prevent billions of dollars in damage, the floodway’s benefits weren’t evenly distributed. “What [it] did was protect the inner core of Winnipeg,” observes political scientist Stephanie Kane, a professor emeritus at Indiana University Bloomington and the author of Just One Rain Away: The Ethnography of River-City Flood Control. “Socially and politically, it also created what I call ‘infrastructural insiders’ and ‘infrastructural outsiders.’ If you live just south of the gate to the floodway, what happens when the Red River floods and is pushing north is [that] part goes through the city and part floods back” south, into the rural areas up the valley. That dynamic, she adds, “is an integral part of any flood control system anywhere: it harms some people and does not harm other people.”

Less than a decade before that Red River calamity, Halifax had found itself precariously isolated when heavy flooding overwhelmed critical transportation routes into the city. Over 36 hours in late September 1942, an unprecedented 230 millimetres of rain fell over eastern Nova Scotia. The downpour isolated downtown Halifax as the rainfall submerged the Fairview underpass, one of two low-lying access routes that traversed the notorious bottleneck between the Halifax peninsula and the city’s western suburbs. The CN rail lines linking Halifax to Truro were submerged for two days while the main highway into the city, which cut under the tracks, became a canal more than 3.5 metres deep. The peninsula, with its 100,000 residents, was cut off from the mainland and supplies of food and other essentials for 12 hours.

According to the Fairview Historical Society, the bottleneck “looked like Niagara Falls with a 40-foot [12-metre] cascade of water spilling down tons of water onto the railway tracks … before flowing down to the Fairview ‘Bottleneck’ blocking it completely.” It didn’t take long for city officials to name the culprit. As the Halifax Herald reported, “The Mayor W.E. Donovan said that the menace of the Fairview Bottleneck to the safety and welfare of the citizens of Halifax now has been conclusively demonstrated.”

Donovan and other members of council realized they needed to address the vulnerability of roads and railway lines that had been disabled in a matter of hours. Within a decade, the city built an overpass at the Fairview bottleneck to ensure that a torrential rain wouldn’t again isolate the Halifax peninsula.

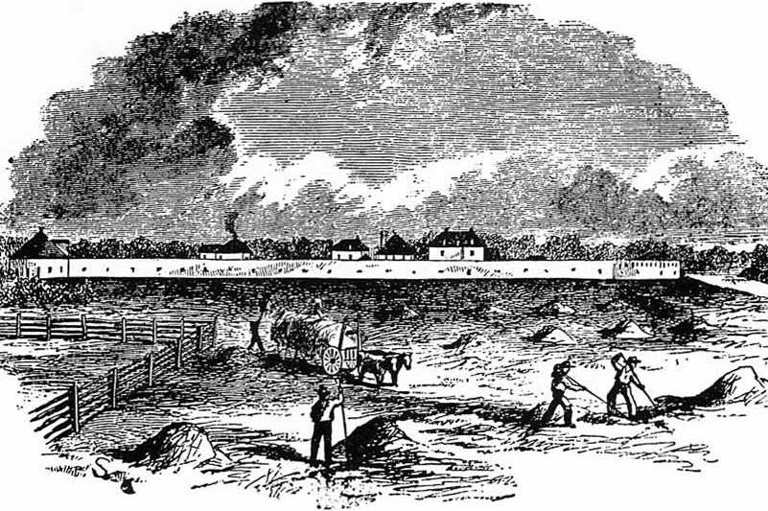

In 1948, at the other end of Canada, inadequate infrastructure — this time in the form of poorly maintained dikes along British Columbia’s lower Fraser River — again played a central role in a game-changing spring flood following a winter that didn’t want to end. There had been a lot of snow, so residents of the lower mainland, mainly farmers and Indigenous Peoples, were expecting a high freshet, which wasn’t all that unusual. The Fraser regularly flooded but did little damage because the waters receded quickly.

Not so in 1948. “Even from the first week of May, we had dike watchers stationed along every section of the Fraser River,” says Kris Foulds, curator of historical collections at The Reach Gallery Museum in Abbotsford, B.C. In the early 2000s, she interviewed numerous residents who lived through the 1948 flood. “They were watching for things like seepage, obviously, and boils that came up behind the dike, but also the dike softening enough that a tree might fall over and rip out a section.”

Initially, the locals weren’t alarmed. Some clambered up the levees to watch detritus float downriver. Farmers methodically moved their livestock to higher ground, while some homeowners arranged to store their furniture in safer places. “It was suggested to people in Matsqui [First Nation] village, which is cheek by jowl to the Fraser, that they were probably going to get four feet of water,” says Foulds. “In the memory of one family, they thought, ‘Oh, well, four feet of water. Well, the house is three feet off the ground. We’ll put Mum’s piano up on bricks and it’ll be safe.’ When they got nine feet of water that came to the roofline, they took a boat up the driveway. The piano keys were floating on the surface.”

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

The dikes near Chilliwack gave way on May 31. “One of the dike watchers I interviewed later said the initial break was about a foot deep and two feet wide,” says Foulds. “Within five minutes, it was four feet deep and 10 feet wide. Two hours later, it was 60 feet wide.” As the fast-moving waters forced their way through, they exposed berms built with crushed cars and tree trunks. “By the time it reached its peak, it was an undisturbed lake between four and 12 feet deep.” The flooding covered an estimated 12,500 to 22,000 hectares, displaced thousands of people, destroyed 2,300 homes and washed out railway tracks.

While this widely photographed event created an unprecedented degree of disruption (along with two deaths), the municipalities along the Fraser did little more than repair the pumphouses and rebuild the breached dikes, using a local clay in an attempt to make them sturdier.

To this day, and despite heavy floods along the lower Fraser in recent years, there’s no political consensus as to which level of government should take responsibility for flood protection. “I just don’t think [the dikes] are maintained as well as they could be,” remarks Foulds, adding that she wouldn’t live on the Matsqui prairie near Abbotsford, despite its rural beauty.

In early October 1954, Hurricane Hazel, a violent tropical storm, veered inland from the Atlantic near North Carolina and roared up through Pennsylvania and New York toward southern Ontario. By the time it reached the Toronto region on Oct. 15, flash floods caused by the Category 4 hurricane rapidly demolished low-lying neighbourhoods along the banks of the Humber River and Etobicoke Creek — communities constructed around the ravines in Toronto’s western suburbs. Dozens of homes were washed away and 81 people died.

The torrent hit Raymore Drive, which ran along the west side of the Humber River, carrying off more than a third of the street and 14 homes; that block accounted for almost half of the night’s casualties. The high death toll, according to a federal government account of the tragedy, had to do with “complacency,” a sense that the Humber could never pose such a grave threat. As a bewildered resident told the Globe and Mail the following day, “I phoned twice to my neighbours to rouse them. I grabbed my cat Smoky, my dog Prince — he’s 16 years old — my bible and an old family picture.… I stepped out the back door into water up to my knees. There was a terrible current. I scrambled around to the side and out the front and by that time the water was up to my waist.”

Hurricane Hazel remains the most lethal, and one of the best remembered, natural disasters in Canada’s history — “a wake-up call for Torontonians,” in the words of Jennifer Bonnell, a historian at Toronto’s York University and author of Reclaiming the Don: An Environmental History of Toronto’s Don River Valley. The sheer devastation also forced something of a political reckoning in Ontario about extreme weather and risk, and marked the beginning of a notably progressive approach to flood protection.

Toronto-area municipalities and the newly formed regional government, informally known as Metro, set to work building flood-control infrastructure — constructing networks of reservoirs in the city’s north end and channelizing portions of the rivers that ran through vulnerable neighbourhoods, including the Humber.

Yet, Hazel’s defining legacy involved land-use planning reform; specifically, the banning of development within flood plains. What’s more, the provincial government expanded the scope of its conservation authorities, agencies mandated to manage land use within specified watersheds that typically extended across municipal boundaries.

The Ontario government established conservation authorities in the 1940s, says Bonnell, to address ecological issues such as reforestation and slope erosion in ravines. The province was a North American pioneer when it came to watershed-based planning. But these agencies came into their own after Hurricane Hazel. “The loss of life on the Humber and the property destruction in the Toronto area, both on the Don and the Humber, made people recognize the precarity of building in flood-plain spaces,” she adds.

The advent of flood-plain management within Toronto’s ravine system marked a 180-degree turn. For generations, the city’s ravines had been used for water-dependent industries, as well as dumping grounds and, later, routes for highways. After Hazel, Metro began acquiring and regulating ravine lands, turning them into parks to mitigate flood-related risk. Queen’s Park established conservation authorities elsewhere in southern Ontario. In this period politicians and members of the public were receptive. “The rise of technocratic authorities in that postwar period is a big part of this story,” Bonnell says. “There wasn’t a lot of push-back.”

However, the effectiveness of watershed management in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) bumped up against the reality that the region’s car-oriented suburbs were increasingly paved-over areas situated upstream from the ravine/river networks. Instead of getting absorbed into the ground, stormwater ended up in sewers and outflows that drained directly into those ravines or the lake. It has continued to cause flooding and slope erosion, especially after severe storms.

In the spring of 1997, Gerald Friesen found himself flying “over a flood coming into Winnipeg. As the airplane came toward [the city] from the east, you could look south all the way to the border [and it was] one giant lake.” He’s referring to another record overflowing of the Red River. Considered a once-in-a-century event, it caused billions of dollars of property damage around the Red River headwaters in North Dakota and Minnesota. While Winnipeg got partially soaked, the infrastructure constructed in the 1960s largely did its job: Duff’s Ditch didn’t overflow its engineered banks. However, as Friesen points out, the berms “barely contained the rising waters. [Then-Premier Gary] Doer’s government got federal assistance to essentially multiply the depth and height of the floodway. That’s been an ongoing project.”

In an era when 100-year storms now occur every five or 10 years and the costs can run into the billions, the legacies of those mid-century disasters have become ever more relevant. In Halifax, for instance, the roads and infrastructure in the Fairview bottleneck have long been built up to prevent a reprise of 1942.

But the consequences along the lower Fraser and in the GTA are more complicated. In British Columbia, the provincial government has divested itself of responsibility for dikes, leaving a patchwork protective system to deal with a river that now carries off ever-larger volumes of melting glaciers. Severe storms in 2007 and 2021 (and in late 2025), when an “atmospheric river” inundated part of the lower Fraser, severely tested dikes that had been rebuilt after 1948. While the local municipalities made repairs, Kim Foulds believes the dikes could be better maintained. Nor have those regions adopted the land-use controls that Ontario promulgated after Hazel. However, the B.C. government since 2021 has sought to better collaborate with local municipalities and First Nations to adopt a more “holistic view of the watershed.”

In the GTA, there have been years of grassroots efforts to shore up ravine slopes and carry out plantings to make flood-vulnerable zones more absorptive. Municipalities have invested millions in constructing park-like flood-protection berms and stormwater holding tanks to prevent polluted run-off from reaching the lake. The three orders of government also spent $1.4 billion to re-naturalize the mouth of the Don River, which has T-boned into an industrial port since 1912, to create an impressively landscaped flood-protection channel.

Yet, Premier Doug Ford’s provincial government has tacked in the opposite direction, removing some of the conservation authorities’ power to carry out the watershed-based land-use planning that was one of the defining lessons of Hurricane Hazel. Almost every summer now features intense storms that leave Toronto’s lakefront areas underwater. “When we see these floods, like we’ve seen over the past number of decades in Toronto, reaching [up to] the windows of the [commuter] train,” says Bonnell, “it’s important to do the work of stitching that back in time [to previous floods] to remind people that this is not a totally anomalous event.

“Water,” she adds, “brings life, but it can also bring ruin.”

While we celebrate Earth Month every April, it's important to remember our impact on nature and the environment every day. The First Nations, Inuit and Metis of Canada understood the importance of living in harmony with nature, and shared that knowledge with new arrivals as early as the 15th century.

If you believe that stories of climate and nature, and their impacts on early Canadians, should be more widely known, help us do more. Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share Indigenous stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!