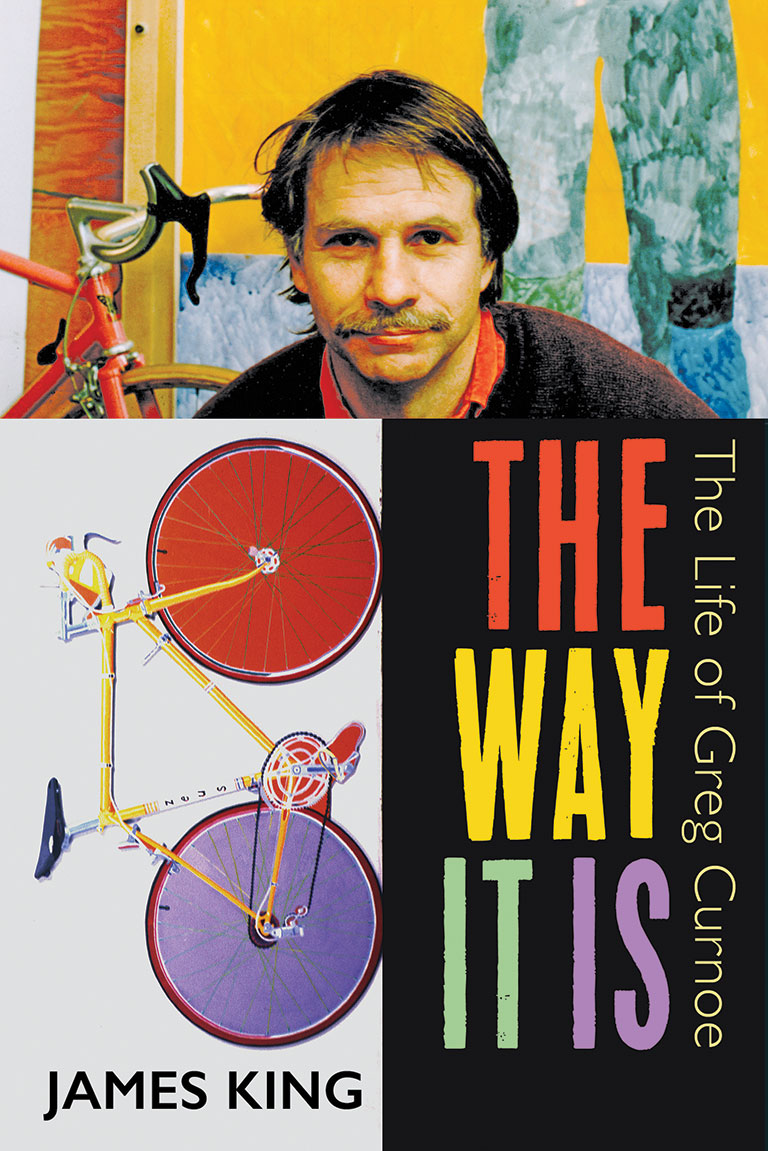

The Way It Is

The Way It Is: The Life of Greg Curnoe

by James King

Dundurn, 392 pages, $45

“What if daily life in Canada is boring??” asks Canadian painter Greg Curnoe in a stamped-letters, watercolour, and gouache piece from 1987. In Curnoe’s restlessly inventive hands, it never was. The London, Ontario-based Curnoe died in 1992 at age fifty-five in a biking accident that cut short a creative life marked by a deep-felt fusion of art and everyday existence.

Thoroughly researched, though sometimes dryly expressed, a new biography by Hamilton-based writer James King paints a picture of a complex, often contradictory artist and man.

A passionate regionalist, Curnoe rejected what he saw as the myopic metropolitanism of Toronto and put down deep roots in his hometown of London. He was fiercely, almost obsessively anti-American. At the same time, he was intellectually open to international and historic influences, drawing on European artists such as Henri Matisse and Marcel Duchamp.

Art critic Gary Michael Dault called Curnoe a “walking autobiography,” and his work often focused on the minute and mundane details of his own life. But he could also be emotionally elusive.

He took loud, obstreperous stances against the official art establishment — and he succeeded in setting up Canadian Artists’ Representation, an organization that still advocates for artists today — but his rebellion sometimes comes off as knee-jerk contrarianism. Curnoe’s working-class identification was partly an affectation, King suggests, and, like many male artists coming of age in the 1950s, his progressive politics did not extend to gender roles.

King, who has also written on David Milne and Lawren Harris, charts Curnoe’s life chronologically, packing in colour illustrations on thick, high-gloss paper that make this a (literally) heavy book.

The artist had a happy, modestly middle-class childhood, became a bit of a misfit adolescent, and then famously flunked out of the Ontario College of Art. “I didn’t fail OCA. OCA failed me,” Curnoe declared.

Returning to London, he set up a studio and proceeded to become an artist, through hard work but also some self-conscious posing. “When attending an opening, he chose deliberately outlandish, loud clothing to call attention to himself as different from others,” King writes.

He also settled down into family life, marrying Sheila Curnoe (née Thompson) and becoming father to three children. In the 1970s, Curnoe got seriously into cycling. Bikes, with their “stripped-down relationship between form and function,” appealed to him and soon became a recurring motif in his painting.

Curnoe’s art was marked by these kinds of faithful, long-running themes, as well as by periodic reinventions. Sheila had often complained about being his model, for example, and in the 1980s Curnoe used himself as a model for a series of unsparing self-portraits that responded to charges by feminist critics that he was objectifying women.

While there are pop-like elements on the surface of some of Curnoe’s paintings, King is rightly wary about classifying him as a pop artist. The larger arc of his work veered toward conceptualism, with its concern for issues of representation and language.

Curnoe was also inspired by the anarchistic spirit of Dada. In 1962 he helped to organize the first neo-Dada “happening” in Canadian art, complete with a “chance sculpture” meant to collapse under the weight of attendees’ winter coats — which is about as Canadian as it gets.

King is warmly sympathetic to his subject, describing Curnoe’s gregarious charm, but he certainly relates enough anecdotes to suggest that Curnoe could be moody, controlling, and difficult. The biography is detailed and comprehensive but too often lists off odd facts — such as that Curnoe picked out Sheila’s shoes for an art opening, and they pinched her feet — without giving much context. In The Way It Is, we glimpse Curnoe’s personality in brief, vivid flashes but never quite see him whole.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Our online store carries a variety of popular gifts for the history lover or Canadiana enthusiast in your life, including silk ties, dress socks, warm mitts and more!