The Art of Commemoration

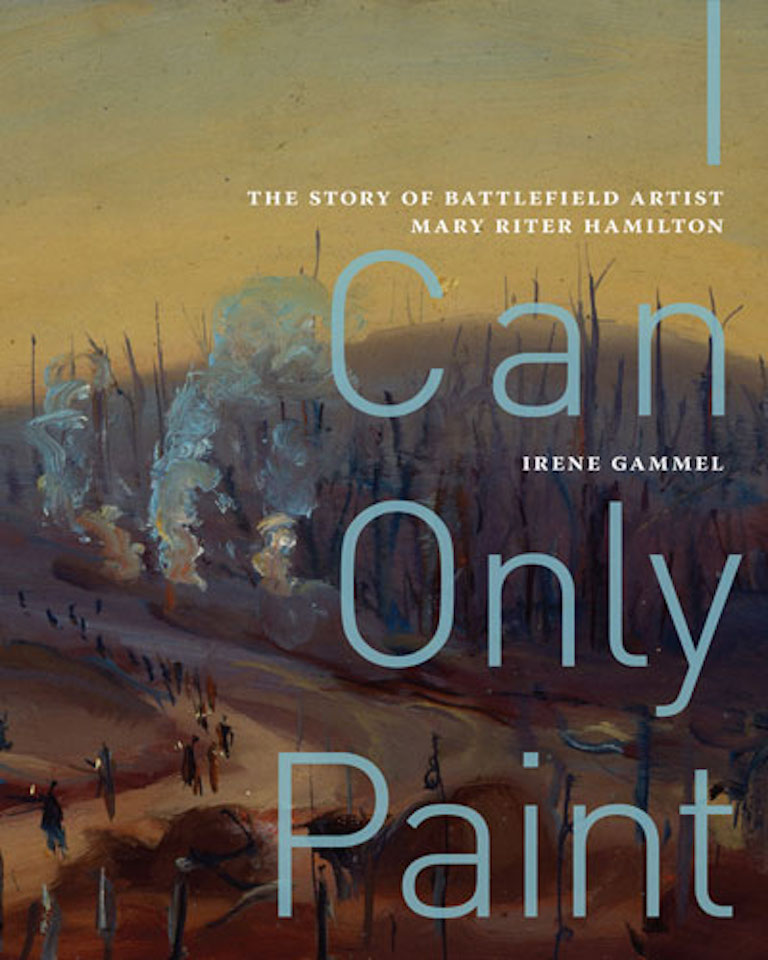

Canadian painter Mary Riter Hamilton had studied in Europe before the First World War, and she wanted to return there to serve as an official war artist. Rejected by the Canadian War Memorials Fund, she instead received a commission from the Amputation Club of British Columbia (now the War Amps) to commemorate those who had been lost during the war.

Beginning in 1919, Hamilton travelled to devastated towns and battlefields in France and Belgium where Canadian soldiers had been active. At the Somme, Vimy Ridge, and the Ypres Salient, she endured difficult conditions that included rough shelter, inadequate food, poor weather, and surroundings littered with unexploded shells. Working sometimes with canvas and at others with available materials such as paper, plywood, and cardboard, Hamilton nonetheless produced more than three hundred paintings between 1919 and 1922. While the work left her physically and emotionally exhausted, Hamilton refused to sell her battlefield paintings and eventually donated them to the Public Archives of Canada.

Irene Gammel’s I Can Only Paint: The Story of Battlefield Artist Mary Riter Hamilton draws from archival research in Canada and Europe as well as previously unpublished letters to place this period of Hamilton’s work in the context of the artist’s life and in relation to other art and war art. The book includes dozens of full-colour reproductions of Hamilton’s paintings as well as maps, photographs, and illustrations. Gammel says Hamilton’s art involves a female perspective that distinguishes it from the work of official Canadian war artists. The following excerpt from I Can Only Paint elucidates how that perspective contributed to some of the paintings Hamilton made in the Ypres Salient, where she explored the emotions and social tensions surrounding commemoration and reconstruction.

Among the ruins of Ypres

by Irene Gammel

For centuries, Ypres, in Flemish Flanders in Belgium, had been world-renowned for its cloth: Far-flung nations clamoured for its fine laces, linens, and wools. All of this changed in 1914 when German soldiers marched through the city on their way to occupy parts of France and Belgium. To prevent them from developing a stronghold so close to the Channel, the British occupied Ypres, with the German army then directing its heavy guns on the city and the surrounding villages. Soon, headlines around the world announced that its iconic Cloth Hall had burned following German bombardment.

The war would maintain its violent grip on Ypres for four excruciating years. The city and its neighbouring villages — such as Boezinge, Dikkebus, Hollebeke, Sint-Jan, Voormezele, and Zillebeke, all of which Hamilton would paint, along with the outlying part of the Ypres Salient, as it was called — became the epicentre of resistance, both physical and symbolic. Here, in the northern part of the Western Front, Allies and Germans attacked and counterattacked ad infinitum. With neither opponent clearly dominating, territory gained was often lost again weeks or just days later.

As in France, here in Ypres the war became stationary and entrenched. Canadians were involved in a number of costly battles for the salient, including the Second Battle of Ypres in 1915 and the Third Battle of Ypres in 1917 (better known as the Battle of Passchendaele). In the process, Ypres became an iconic war town, much like French Verdun to the southeast along the same Western Front. With an unforgettable photograph of the burning Cloth Hall distributed by mass media around the world, Ypres was forever branded a Great War city in the global imagination.

The iconic photograph of the Cloth Hall in flames was taken by brothers Maurice and Robert Antony. Robert was an official army photographer for Belgium, and the Antony family ran a photography studio on Rue du Beurre (Boterstraat) in Ypres. By 1919, the brothers had been commissioned to photograph the war graves and the reconstruction. During this process, on June 12, they photographed a woman painting the Cloth Hall.

Like a wide-angle panning frame from a movie, the image shows an artist in a trench coat and brimmed hat making a drawing with a long street of ruins and debris curving behind her on the Rue du Beurre. She stands in profile, precisely aligned with the hall, which rises above the destroyed town. As the tall grasses swallow her feet, she takes a step closer to her easel. Her coat crinkles as her arm angles toward the canvas. Mouth set in a thin concentrated line, her hand becomes her active entry point for the war scene, the tool through which the scene becomes knowable to both artist and viewer.

The In Flanders Fields Museum’s researchers have identified the painter as likely Mary Riter Hamilton. This would make her among the earliest visitors to Ypres, in early June 1919, after the mayor had first unlatched the city gates to civilians in an effort to return militarized Ypres to postwar normalcy. A similar woman, photographed painting in July, was likewise identified as Hamilton. This time she is standing in the marketplace, painting the Cloth Hall, which almost exactly matches the scene in Hamilton’s oil on plywood Ypres, Belgium, 1920, Early Morning. Although this painting is dated 1920 and is smaller, it has the same proportion, and, of course, it’s entirely possible that she made a copy of her 1919 work.

Why did Ypres assume such a central role in Hamilton’s work? Given the presence of Canadians here, Hamilton had first expressed her interest in the city in her letter to Sir (Byron) Edmund Walker of the National Gallery’s advisory board in 1917. Once overseas, Hamilton was able to immerse herself in the destroyed city in order to explore the postwar social tensions surrounding commemoration. Moreover, she witnessed the rapid emergence of a commemorative and cultural industry of war and peace, the beginnings of what Jay Winter calls “the memory boom,” which continues to this day with over four hundred thousand visitors each year, and double that number in 2014 during the centenary. ...

Even as she paints a scene of official commemoration, Hamilton chooses to foreground those who stand on the sidelines

In Ypres, the tourist industry would become highly contested, and Hamilton would immerse herself in these tensions, which soon fuelled her artwork. For Hamilton, Ypres’s landmark sites — the Cloth Hall, the ramparts, and the Menin Gate, as well as the many battlefields of the Ypres Salient — would communicate this duality of destruction and reconstruction, of safeguarding memory sites while also rebuilding imaginatively and materially. ...

On Thursday, May 19, 1920, Hamilton was part of the crowd on the overcast afternoon when Ypres was decked out in Belgian flags that underscored the celebratory mood. Many international visitors and journalists had come to witness what the London Illustrated Times called “the scene of an unprecedented event.” With King Albert of Belgium present, Field-Marshal Lord John Denton Pinkstone French, Earl of Ypres, awarded the city the Military Cross, acknowledging its suffering and resilience during the war.

Ypres’s beloved mayor accepted this honour on behalf of his city, as Hamilton’s title describes: Ypres Honours the Acting Mayor of 1914 (1920). The colourful flags and her inscription on the painting’s verso, “Ypres En Fete ...,” recall Claude Monet’s La rue Montorgueil à Paris, Fête du 30 Juin 1878 (1878), which shows the streets filled with people and flags as a tribute to the city’s recovery after a lost war, igniting a democratic élan in the still fragile republic. Like Monet, Hamilton is an observer of the scene, with the colours of a multitude of Belgian flags igniting the grey of the Cloth Hall, where military and civilians have gathered in a key ritual of community-affirmation after the war. Standing at the edges to the left are parents with children, including a particularly striking parent-and-child pair dressed in the tartan-inspired garments of the Highlanders.

The collective ritual shows the way forward in shaping a new post-war society. Even as she paints a scene of official commemoration, Hamilton chooses to foreground those who stand on the sidelines. While she does not give her figures faces, this emphasis signals the interplay between individual and collective in a postwar, democratic spirit. Her visual assembling of dispersed groups in celebration bolsters the theme of reconstruction and new civic life. Her collection as a whole prominently includes women and children, referencing, on one hand, the absence of men and the death of soldiers, and on the other a new postwar vision of Canada as a nation concerned with themes of peace and reconstruction. ...

Hamilton spent the spring of 1920 in pursuit of signs of rebirth as a means of healing not only the mind but also a cross-national humanity that had suffered through the war and would even- tually become the recipient of these paintings. Her painting on paper Filling the Shell Holes in No Man’s Land (1920) reflects this recuperative shift. Working in a soggy landscape that could be Passchendaele, with the same cadaverous trees as in Shrapnel Corner, Flanders (1920), two nameless men proclaim the era of reconstruction.

The workers are faceless, and their non-matching uniforms — one wearing a white cap and brown trousers, the other a blue cap and blue trousers — suggest that they might be Chinese labourers, who were known for such motley uniforms. These labourers worked alongside Hamilton, and, while typically marginalized in her collection, they seem to be represented here — albeit without being named in her title. Wielding shovels on the battlefields, they work in tandem to repair the war’s damage. A third spade is resting in a hole to the right, a rhetorical call to the viewer to join in and help rebuild a habitable landscape.

As these two men confront the landscape, viewers are left to contemplate the restoration work that continues a hundred years on. Like the seedlings of Mine Crater — Hooghe, the smallest objects can bear significant symbolic weight. Hamilton recognized this. The rare verb of her title — Filling the Shell Holes — is key, as filling the holes is like bandaging wounds, initiating the healing of the earth and of society through repair and restoration before rebuilding can begin. This is a process that requires community action. “No man is an island, entire of itself,” as John Donne writes, and this first truly global con- flict had made that truth palpable — down to every individual shell hole.

Hamilton may have used the painting of these sites of consolation as a way of holding her own stress and trauma at bay. She applied these salvaging techniques to two key sites where Canadians had fought, creating iconic paintings. She performed a special kind of salvaging at Sanctuary Wood (Hill 62), a distinctly Canadian site in the Battle of Mount Sorrel, fought and lost by Canadians in 1916. A.Y. Jackson, who was wounded in this battle in June 1916, refused to paint it, while Hamilton painted it as an uncanny space that denies full entrance.

Sanctuary Wood (1920), at 45.7 by 59.1 centimetres, is one of her mid- to large-sized paintings, with exquisitely honed details. Here, Hamilton’s composition puts the underbrush in the foreground. With a felled tree immediately obstructing the viewer’s entrance, this is not a trail for the living to tread; she marks it off as a sanctuary to salvage. The midfield depicts a line of tree trunks — all splintered with limbs blown off. Intricate purple shadows of mourning seem to resuscitate these splinters, inviting viewers to contemplate from a distance this otherworldly space imbued with the spirit of the dead.

In painting this scene, she did not claim to paint her own affect but rather, as she told a journalist, that of the soldiers, expressing in these words the motivation for her entire expedition: “If as you and others tell me, there is something of the suffering and heroism of the war in my pictures it is because at that moment the spirit of those who fought and died seemed to linger in the air. Every splintered tree and scarred clod spoke of their sacrifice.” In the painting, the splintered tree trunks stand like the ecstatic figures in El Greco’s Fifth Seal of the Apocalypse (1608– 14), the largest tree to the left mirroring the position of John the Baptist’s witnessing of the Apocalypse. By engaging the art of El Greco to articulate both the chaos of the battlefield and the inchoate emotions of mourning in the wake of violent death, her painting seems to suggest that the community cannot be reintegrated through the evocation of the bodies of the dead. Instead, the artist calls upon art to hold off the despair of death.

“The spirit of those who fought and died seemed to linger in the air. Every splintered tree and scarred clod spoke of their sacrifice.”

Likewise, at Passchendaele, the site of heavy fighting and extraordinary losses for both sides, Hamilton focused on consolidating emotions. The result was Canadian Monument, Passchendaele Ridge (circa 1920), one of her most iconic paintings, showing the cone-shaped memorial adorned with a dark-gold plaque framed in fine burgundy. Set in the battlefield, it rises against a bright sky, ethereal and luminous. The memorial had been built by the Nova Scotia Highlanders, known colloquially as the Neverfails men, whose battalion had been decimated here in October 1917. The surviving soldiers paid tribute to their comrades on the site of their former headquarters. In the painting, mud-covered rifles lean on the base, emphasizing the structure’s verticality. A helmet hangs on the fence post. This spontaneous work of commemorative art evinces the soldiers’ empathy, their “soldiers’ heart” on display, with the curated pieces functioning like trench art, as “objectifications of loss ... and as materializations of the relationships between object and maker ... and the living and the dead,” wrote Nicholas Saunders.

These artifacts remind the viewer of the deeply personal experience of each individuated loss — a profound sentiment that is rarely captured by official national monuments. Hamilton signed her improvised canvas in the same red-brown colour in which she rendered the mementoes that decorate the scene, drawing a provocative parallel between herself — a trained artist without government accreditation — and the soldiers sent to the battlefields by their country but nonetheless sovereign in their commemorative practice. Scribbling on the back and mixing two languages, she dedicated the painting: “To 85th Batt to 148 Officiers & Men.”

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Our online store carries a variety of popular gifts for the history lover or Canadiana enthusiast in your life, including silk ties, dress socks, warm mitts and more!