Speaking for his compatriots

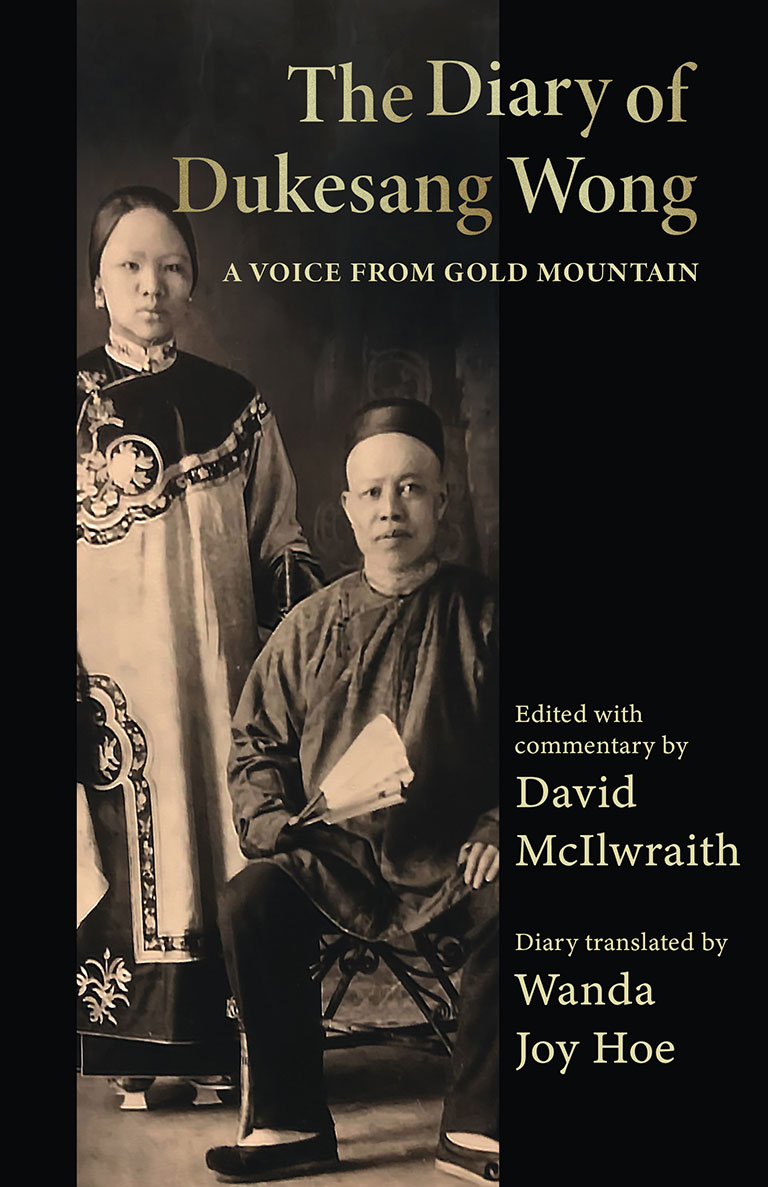

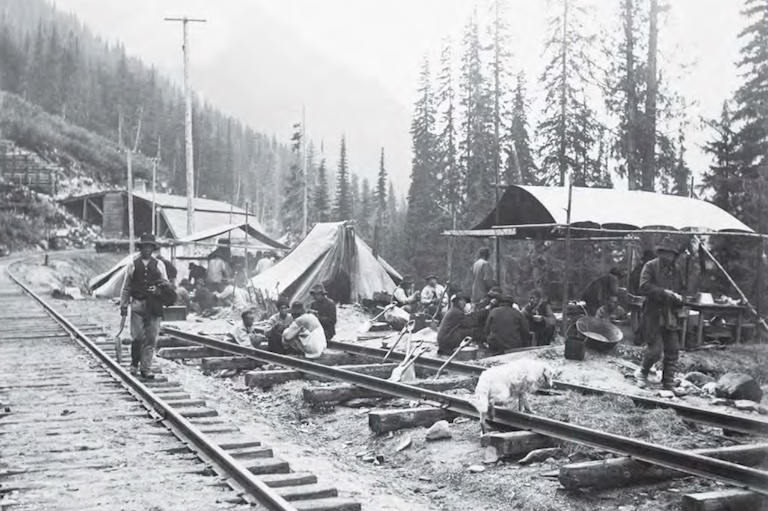

After travelling from his village in China to Portland, Oregon, Dukesang Wong accepted work on the Canadian Pacific Railway and journeyed in 1881 to “the Saltwater City” of New Westminster, then the largest city on the B.C. mainland. The diaries he maintained both in China and in western North America — “the Land of the Golden Mountains” — record his many gruelling experiences, his shock and bemusement at certain Western ways, and his appreciation for the land and for many of the people he encountered.

After working several years to save money, Wong established himself in a tailoring business in New Westminster and returned to China to bring Lin, who had been promised years earlier as his future wife. His diaries were eventually destroyed in a fire, but his granddaughter Wanda Joy Hoe had translated portions of them as part of her university studies, and selections have now been published as The Diary of Dukesang Wong: A Voice from Gold Mountain. They’re described as “the only known first-person account by a Chinese worker on the construction of the CPR.”

The following passages were written during Wong’s first difficult years in British Columbia. As editor David McIlwraith notes, “Wong rarely mentions the names of the towns and villages he travelled through and worked in.” Life as part of a railway work crew was often exceedingly difficult, and a head tax on Chinese immigrants to Canada was initiated in 1885. Yet Wong’s perceptions of life in his new land change as he foresees the possibility of establishing himself in Canada and as he rues the violence happening in his homeland.

A land already full of sadness

by Dukesang Wong

Autumn 1881

It is hard, this labouring, but my body seems to be strong enough. The people working with me are good, strong men. There are many of us working here, but the laying of the railroad progresses very slowly. It seems we move two stones a day! And they want this railway built across these high mountains, some two thousand miles! Even over the plains of our homeland, such railways took over a generation to build, so I can imagine these white people will face failed dreams. ...

I have been honoured today. The Chinese workers have elected me as their spokesman with the contractor, to speak of our good deeds. I am truly surprised that the workers did not choose Chen [Wong’s friend], since he is more proficient in English. I can speak much better in the learned language of our people, but English is hard to speak. However, I must try to obtain better medicine and food for us to eat. We won’t be strong if we do not have enough food in our stomachs.

Spring 1882

Many Chinese people are here now, working on this railway. Some are from the Big City and many others are from Kwangchow and the Canton area, speaking in their village language. It is a little difficult to be a spokesman for them, as their language is hard to understand, and they aren’t able to write. Chen has returned to his home village. I miss his company, and I would also like to return to our homeland.

Yesterday, I returned from Victoria. It is a beautiful and clean city compared to this town in the mountains. I became known to the Indians here during the trip, and their help in the return journey was great. They are solitary people, but they know the land so well. My experience is so limited in those small boats in which it is so hard to travel. How I wished to have a horse to ride!

I despair at being able to save so little these days, but the small garden Chen left in my care has been helping my food supply. How good the fresh green vegetables taste. If only it was warm enough, I could become truly well by eating fresh food.

Early Autumn 1883

My soul cries out. I wish I had never experienced such bad days as those in which we now live. Many of our people have been so very ill for such a long time, and there has been no medicine nor good food to give them. Even the strongest of us are weak without medicine to fight against these diseases, which spread very rapidly. It is such a sorrowful sight. The white doctor has told us the illnesses come from lack of fresh food, but we cannot grow any fresh food, as all of us, including the white people, are moving constantly with the work we have to do. The good doctor has gone to the larger town in search of better food for the very ill, but I am afraid that the medicines will not arrive here to these poor gutter-shelters. I would have liked to accompany him, but my body does not have the strength or desire.

These are troubled times for us Chinese. There has been word among the employing company that we are not good workers and do not work enough for the schedules and plans of the railway owners. How does anyone work when so ill? Many are killed when such words are spoken, and we are becoming more like dogs biting at one another. My meagre attempts at talking about being humble and waiting for better days are senseless. My words mean less than nothing. I am of so little help to everyone.

These mighty lands are great to gaze upon, but the laws made here are so small

The frost has fallen early and only the bok choy survives in my boxes. I wonder when I shall have laboured enough to journey back to my home village. Perhaps I will not ever be able to return, but how I long for those childhood days. Chen has sent words that tell of turmoil in China, but he does not say where.

1885

I am truly alone amid the dying. The leaders of the white people demand money — our poor savings — taken from we who have so little, given to those who are not so taxed. Some who are very ill have taken to spending their days in the opium shacks, with little food and even less strength. This is a bad omen.

At last the frost has left and the grass grows on the hills. The life around my shelter is starting again, and my soul feels much less burdened. We have been burying some of the people who died over the hard, foodless days, but the sight of those dead is hard. Wing Sun’s savings were not enough even to send his body to the Saltwater City, and I walked to his grave today to apologize. Wan Chu derided me for bowing, but it is in our traditions and manner to do so. The dead are higher in station than we who remain on this earth. Wan said we must follow the ways of the white people, so that we are not considered separate and strange by them. But they bury their dead so casually and never show signs of remembrance or honour. The dead once lived among us and also moulded our lives, making it imperative that we honour them as we carry them with us.

There is much work to be done and not enough people to labour at it. So many of us Chinese suffered and died recently; I cannot recount them all. But the Western people will not allow us to land here any longer, while they scold us for not working enough. How these acts wear my soul down to nothing. Kwong tells us about the laws the white people have enacted to prohibit any further landing of our people. I cannot understand why. The work is great, and there aren’t enough labourers. The Indians are not working these days, and the Hindu people cannot labour as we are able to. But my words are meaningless, and my strength to speak now falls upon deaf ears and closed eyes. These mighty lands are great to gaze upon, but the laws made here are so small.

Spring 1886

For many days now I have been so tired that I could not continue to write in this journal. ...

I am told that there are three men of my village over here in the Land of the Golden Mountains. They are said to be in a settlement north of this town. Perhaps I’ll soon be able to visit their settlement and talk with them about our home village. It has been a very long time since I have heard any words spoken in my own language and about the news of my homeland.

Summer 1886

Work has brought us back to the Saltwater City. There is some fresh food for us and enough fish to fill our stomachs. So many have suffered from diseases and have been working their skin off, appearing more like skeletons, so sick without food and rest. Even the fresh food here will have little effect on some of the poor frail bodies, but all of us are greatly relieved. ...

Times for us now are definitely changing, and the fortunes of our people need great care and guarding. There is so little we can do to change the way the white people see us, yet I do wish the weight of taxes on us was gone. One good event took place a few days ago, however – tea! Loads of tea for sipping. My young neighbour has prepared a feast for us to accompany the tea, and we all delight in these days.

Today, as it is a feast day in the Western calendar, all the labourers are free to follow their own will. I decided to wander in the hills of this land. There are few books to read, and my own are too well read to interest me in any new way, so I will compose a few words about my own thoughts and ideas. I have pondered this fresh new land, yet it is a land already full of sadness. The people are beginning to pursue a search for gold. They say it glitters everywhere, and men die for it. It is a peculiar set of values, strange to my humble limited experience, where men fight one another for it. The masters have said, “Only ill will come from desiring material things one cannot obtain; only good will come from desiring good.” I desire material things sufficient for my living, and to bring Lin to an established house. The glitter of gold will not bring her to me. It would be only too easily robbed from me, so I labour onward, being called foolish by some people. Is it a fool’s dream to want to establish myself, to be well respected and a full man? In my home village, if people could see what goes on here, they would surely despise the violence there and leave the village for the invaders to conquer. ...

Early Winter 1886

In my meditation last evening, I formed a decision. I will work here in this town, doing tailoring, in order to establish a house and have a good name among the Chinese here. Tailoring is a worthwhile trade that I can perform, and it will also help people who cannot purchase clothing from Western tailors. There is not enough ready-made clothing from China, and there are no tailors to cut the cloth in our manner. I will be able to earn some money, enough to bring Lin over to this land. I am afraid for her life in our homeland, since all her family perished and she has no place to go. ...

Late Summer 1887

The coastal regions were certainly cooler than this place. The land is very dry, and dust continually cakes onto our skin as we work. Today I had to be treated by the town physician for exhaustion in my lungs. I need to rest, but I have yet to obtain enough funds to return to the Saltwater City to build a place to start tailoring. I thought that my strength was built up sufficiently in the south, but this land is far harsher and demands more strength than I have. I have been here for seven months and have only been doing labour on the railway. Mining coal brings more money, but the owners of the mines will no longer allow us poor people to work for them. There are no Chinese families here who I could teach, although the white people have schools for their children. I am very interested in their teachings and wish I could understand enough of their language to listen to their lessons. My old way of life — my soul desires it, and my mind continually wanders to those days of no cares and worries. My dear father, if only you can see me now, labouring, using my physical strength to earn some food and hoarding the money paid to me! ...

Is it a fool’s dream to want to establish myself, to be well respected and a full man?

Late Autumn 1887

At last a ship full of our people’s goods has arrived bringing such joy! We have teas and rice. We have spices and dried food. We will have a full year’s celebration with such fortune!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Our online store carries a variety of popular gifts for the history lover or Canadiana enthusiast in your life, including silk ties, dress socks, warm mitts and more!