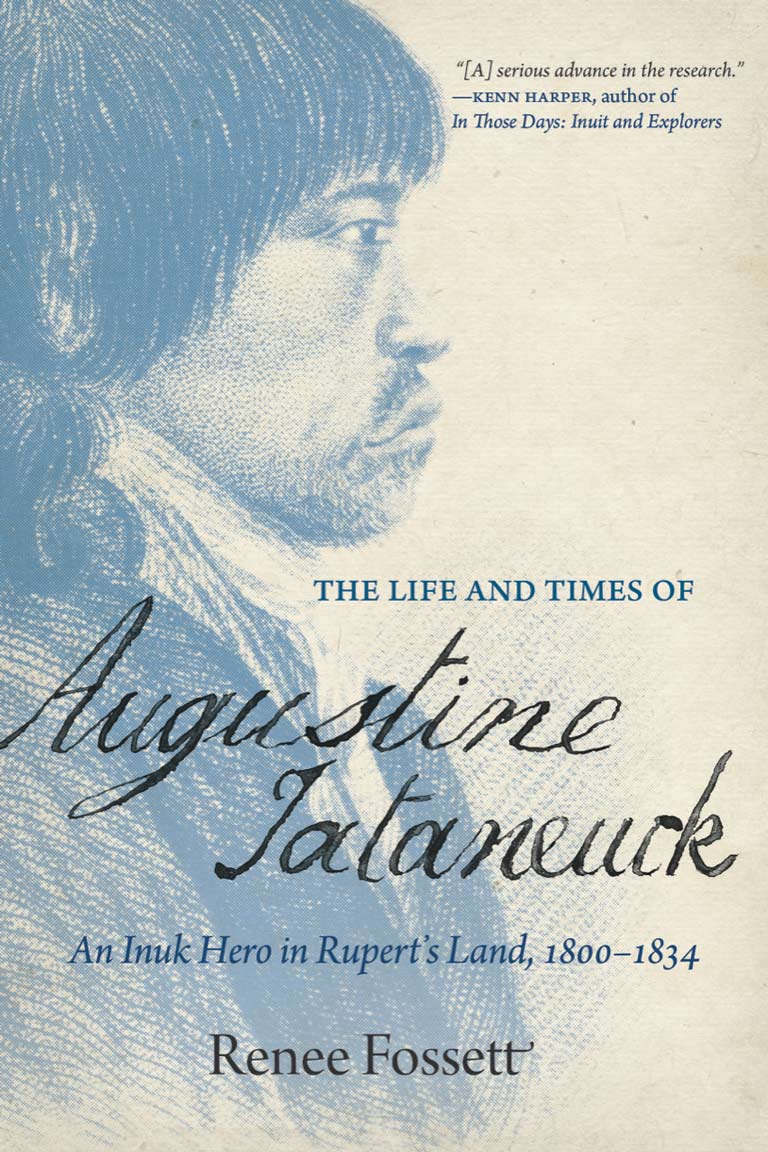

The Life and Times of Augustine Tataneuck

The Life and Times of Augustine Tataneuck: An Inuk Hero in Rupert’s Land, 1800–1834

by Renee Fossett

University of Regina Press

424 pages, $36.95

It was July 1826, and British naval officer John Franklin was in quite a pickle: A group of Inuit had led his two vessels onto a tidal flat on the Mackenzie River Delta, and these “guides” were now clambering onto the grounded boats and stealing everything they could lay their hands on.

Franklin’s Inuit interpreter, Augustine Tataneuck, immediately leaped into the water, shouting at the pillagers until he was hoarse. Later, when the boats were lifted by the incoming tide and the looters had been scared off by the raised muskets of Franklin’s sailors, an unarmed Tataneuck waded ashore and gave the forty or so Inuit armed with bows and arrows a good scolding.

He shamed “the delta people with the observation that no other Inuit had ever been known to act with such rudeness,” writes author and historian Renee Fossett. She adds that Tataneuck reminded them that all of the white men had guns and could have killed them if they had wanted. The Inuit men agreed to back off and gave some of the purloined articles back, after which Tataneuck joined them in a celebration of dancing and singing.

Franklin was duly impressed with Tataneuck’s skill at defusing conflict — in this and in other incidents that took place on his Arctic expeditions.

Tataneuck is among the few Inuk interpreters named in the historical record of Hudson’s Bay Company accounts, or in the journals and letters of traders, missionaries, or explorers like Franklin. Consequently, according to Fossett, “we know more about his life than we know about any other Inuk who lived two centuries ago.”

Fossett stumbled upon Tataneuck’s name while researching something else, and she became curious about him after discovering that his family had left him in the care of the HBC in Churchill, in present-day northern Manitoba, around the age of twelve. It was not uncommon for Inuit youth to be apprenticed at HBC trading posts. The company viewed them as potential future interpreters and guides, while Inuit families wanted their youth to establish family-like ties with the company to gain favoured trading status and other benefits.

Most stayed for a year and returned to their communities, but Tataneuck took the unusual step of making a career with the fur-trading company. Aside from learning the various chores that were required of a labourer at the post, he learned to read and to write. And, while there is no known record of anything he wrote beyond his neat signature, which appears on the cover of the book, Fossett has been able to piece together aspects of Tataneuck’s life and personality. We even know what he looked like, since one of Franklin’s officers, George Back, sketched his profile.

Still, the facts about Tataneuck are scant. For instance, little is known about his family and community. He had a wife and children, but their names were not recorded. So Fossett’s book is less a biography than a fascinating description of Tataneuck’s circumstances — the daily life and routines of the posts at Churchill and York Factory, the Franklin expeditions in which he participated, and the impact of the unusually cold climate of that time.

That climate led to widespread starvation among the Inuit and probably affected Tataneuck’s decision to stay with the HBC, since his wages helped to sustain his community. Indeed, his family continued to draw from his HBC account for up to twenty years after his death.

Fossett skilfully draws out glimpses of his character, such as when she notes that he was very happy to be issued with a blue serge jacket and other items resembling what seamen with the Royal Navy wore. He used his splashy clothes to make an impression when negotiating with the Inuit people who were encountered on Franklin’s expeditions.

Interestingly, some of Tataneuck’s HBC bosses described him as being too proud to do the drudge work of the trading post, following his remarkable adventures with Franklin. And who could blame him?

Fans of Arctic history will find this book a highly engaging read.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.