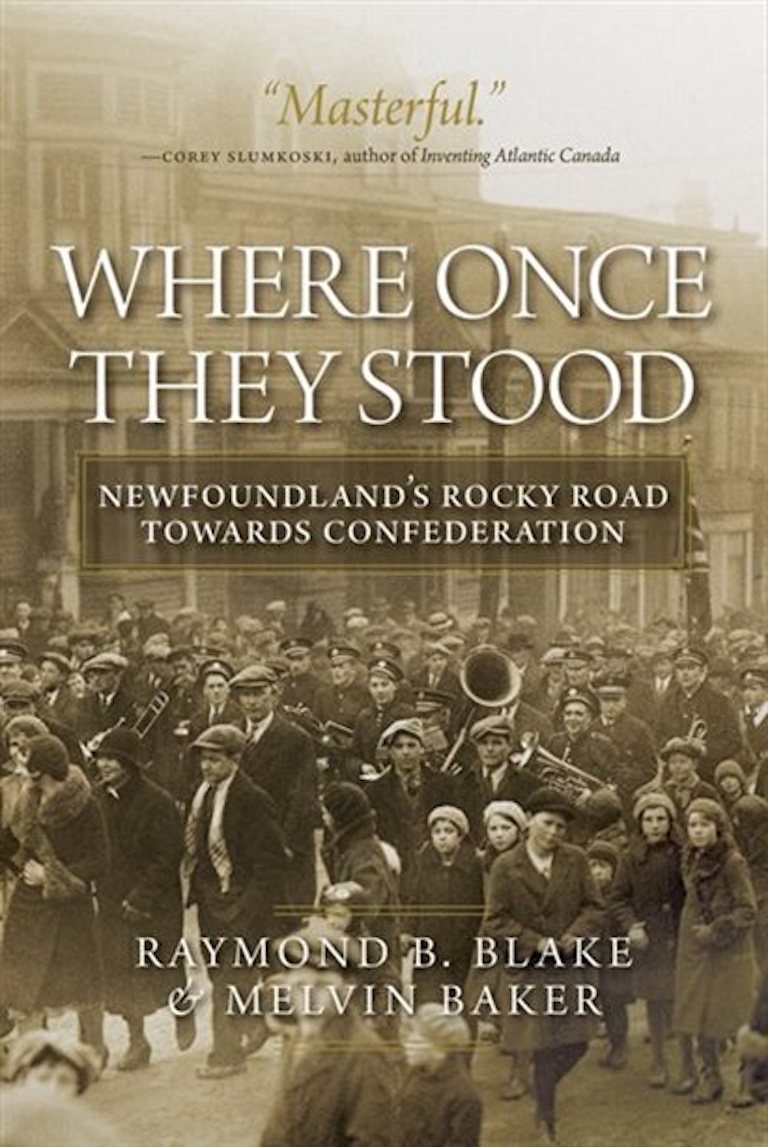

Where Once They Stood

Where Once They Stood: Newfoundland’s Rocky Road Towards Confederation

by Raymond B. Blake and Melvin Baker

University of Regina Press,

413 pages, $34.95

Enter any gift shop in St. John’s, N.L., and you will undoubtedly notice a selection of souvenirs featuring a distinct tricolour flag of pink, white, and green. While never adopted as an official flag of Newfoundland — even its origins and early uses are uncertain — today the “republic” flag is a symbol of Newfoundland pride and independence.

The 1949 entry into Confederation of Canada’s youngest province — which has since been renamed Newfoundland and Labrador — is still a part of living memory for some. It followed a divisive period that remains contested and debated even seventy years later.

In their recent book, Where Once They Stood: Newfoundland’s Rocky Road Towards Confederation, historians Raymond B. Blake and Melvin Baker examine the province’s long journey towards union with Canada.

In particular, they seek to explain why Newfoundlanders rejected attempts at Confederation in the 1860s but then accepted union, albeit by a narrow margin, in 1948. They challenge popular and persistent notions that Newfoundlanders were duped into joining Confederation and instead characterize their decisions as complex, nuanced, and informed.

The now-province’s story regarding Confederation began in 1864, when two delegates — Frederic Carter and Ambrose Shea — attended the Quebec Conference at the invitation of John A. Macdonald. Carter and Shea attended the proceedings merely as observers, but they returned from the conference as enthusiastic supporters for Newfoundland’s union with Canada.

With the two men having become serious proponents of Canadian Confederation, it is apt — and somewhat prophetic — that both appear in the famous photographs and paintings capturing the Fathers of Confederation at Quebec.

The 1869 Newfoundland general election was fought primarily on the issue of Confederation. Since 1854, Newfoundland had been a self-governing colony, like the other British colonies in North America. However, the issues that persuaded Nova Scotia and New Brunswick to join Confederation, including the threat of American expansionism and the promise of a continental railway, did not resonate in the same way with Newfoundlanders. Ultimately, the anti-confederate movement landed a strong victory, winning twenty-one of the thirty seats.

The issue of Confederation wasn’t again raised in a serious way until after the Second World War. By that time, following years of economic difficulties resulting from the First World War and the Great Depression, Newfoundland had been placed under a British Commission of Government.

The Second World War, however, brought renewed prosperity, and both Britain and Newfoundland agreed that it was time to reconsider Newfoundland’s future.

Unlike any other province in Canada, the matter was put to the citizens of Newfoundland in two referenda in 1948. Canadian Confederation emerged as the choice of the people, receiving fifty-two per cent of the vote.

The main difference between the 1860s and the late 1940s, Blake and Baker argue, is that postwar Newfoundlanders were seeking a form of what the authors describe as “social citizenship.”

In Newfoundland — and in many other Western democracies in the postwar world — there was a new belief that the state should have a greater responsibility in areas like health care and social welfare, in order to “build sustainable and vibrant communities, and to achieve social cohesion.”

The pro-confederates, led largely by Joseph Smallwood, campaigned widely on this issue. They took great efforts to deliver their message to families in outport communities, including, very importantly, to women. By contrast, the anti-confederate movement failed to recognize this shift in popular opinion, even going so far as to characterize Canada’s social programs as immoral.

In Where Once They Stood, Blake and Baker take a broad political-history perspective while centring their argument on voter agency and competence. Through detailed and sophisticated research, they demonstrate that, as in the 1860s and 1940s, the power lies with the people.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement