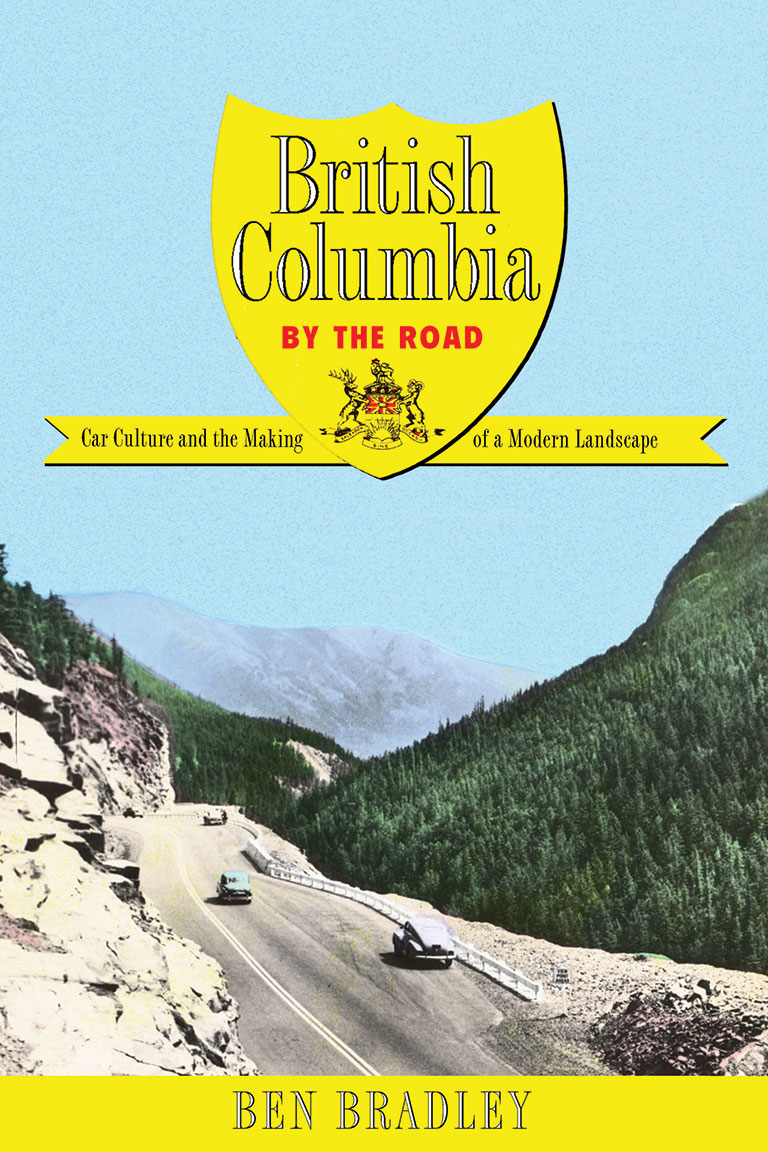

British Columbia by the Road

British Columbia by the Road: Car Culture and the Making of a Modern Landscape

by Ben Bradley

UBC Press, 309 pages, $34.95

The geography of British Columbia’s Interior, with its mountains, valleys, and passes, has posed many problems for road builders over the years. But geography is not the only factor; politics have played a role as well.

The desires of various governments to promote this or to discount that have helped to dictate not only where roads are placed but also what has appeared next to those roads.

In British Columbia by the Road, Ben Bradley provides numerous examples of the ways government policies have shaped the routes that are travelled today. Along the way, he gives readers repeated lessons on Fordism, which he identifies as the mid-twentieth-century “political-economic ‘moment’ that saw the state take an active role in regulating, stabilizing, and sometimes stimulating the economy.”

This is not a comprehensive history of highways in province, or even in the province’s interior. Bradley gives the most attention to two major routes — the Hope-Princeton Highway and the Big Bend Highway. The Hope-Princeton, which opened in 1949, remains one of the key links between the Lower Mainland and the Okanagan Valley — although its importance has been diminished in recent decades by the Coquihalla Highway.

Throughout its existence, the Hope-Princeton Highway has provided a gateway to Manning Provincial Park, a destination that was given a high priority by government. Signs of civilization, such as telephone lines, were kept away from the road. After a forest fire, the park’s boundaries were extended so that eastbound highway travellers would see greenery before they saw the devastation caused by the flames.

Another provincial park, Hamber, was many times larger than Manning — but it was only accessible by the miserable Big Bend Highway, was not as scenic as Manning, and was under pressure because of the government’s interest in getting at the resources within its boundaries. With the eastern half of that highway destined to go under water after the Mica Dam was completed in 1973, the park was reduced to about two per cent of its previous size.

History was a factor in highway development, with attractions such as Barkerville and Fort Steele refurbished and reshaped with highway traffic in mind. And then there is Three Valley Gap, which is impossible to miss when driving along the Trans-Canada Highway. It is not as historic as it looks and was created with tourist traffic in mind.

History has also been marked, since 1958, with signs that promote stops of interest along major routes. These signs, located at convenient pullouts, primarily commemorated the accomplishments of white males, although the more recent expansion of the sign program has helped to bring more diversity.

British Columbia by the Road is a fascinating book and provides enough background information to settle many an argument. It is, however, not quite as expansive as its title might suggest. By limiting its coverage to the southern Interior, it ignores the Lower Mainland, Vancouver Island, and the province’s North — all areas with interesting stories about highways.

It also appears that Bradley tried to bridge the gap between academic and popular writing. Too often his book reads like a thesis on Fordism, with highways and provincial parks used to prove key points. Unfortunately, the many references to Fordist actions take away from the narrative.

That said, the amount of research that went into this volume is as breathtaking as the views from Skagit Bluffs on the Hope-Princeton Highway. British Columbia by the Road is a fine history that helps to explain why we see what we see as we drive in the province’s interior. It’s well worth reading before your next drive.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Our online store carries a variety of popular gifts for the history lover or Canadiana enthusiast in your life, including silk ties, dress socks, warm mitts and more!