Prairie Prodigy

In his first major tournament, the fourteen-year-old Canadian looked up from his chessboard and surveyed the ornate surroundings of the playing hall — a nineteenth-century Buenos Aires opera theatre, clad in green-and-black marble. He returned his gaze to the board, picked up his rook, and unleashed one of the most memorable moves in the history of chess.

The date was August 30, 1939, two days before the outbreak of the Second World War. But, in the Teatro Politeama opera house in the Argentinian capital, the 133 competitors at the eighth Chess Olympiad — among them many of the world’s best — were focused on which country would claim supremacy on the board. The young Canadian was Abe Yanofsky of Winnipeg, already one of the top players in his country. By the time Yanofsky reached his twenty-second move, it seemed that his opponent — Peru’s reigning national champion, Alberto Dulanto — had driven the teenager to the brink of disaster. Any move Yanofsky could make appeared to lead either to the loss of his queen or to immediate checkmate. But Yanofsky peered deeply into the position and played a surprise sacrifice of his rook, forcing his opponent’s king into the open and leading to Dulanto’s resignation a few moves later.

The game was a sensation. The Argentine media declared that a new prodigy had been discovered. The world chess champion, Alexander Alekhine — a Russian-born French citizen — immediately took a huge interest in Yanofsky. For the remainder of the tournament, Alekhine made time after each of Yanofsky’s games to review it with the young player and to analyze what he had done right and wrong.

“The whole little game is characteristic of the incisive style of the young Canadian who was practically the only revelation of the Buenos Aires team tournament,” the world champion later wrote in his book 107 Great Chess Battles, 1939–1945. Yanofsky scored nine wins and one draw in the tournament’s final phase, earning him a silver cigarette holder and a medal for individual performance — although the Canadian team as a whole placed only seventeenth overall. His game against Dulanto was eventually included in British chess master Graham Burgess’s compilation Chess Highlights of the 20th Century.

Who was this teenager playing in his first serious international competition? At the time of his triumph in Argentina, Yanofsky had been playing chess for only six years. His father had taught him at the age of eight, and he was soon beating adult competitors. Chess players in Winnipeg’s Jewish community had taken him under their wing, spotting a unique prodigy and helping him to advance in his career.

Yanofsky went on to win eight Canadian championships and became Canada’s first grandmaster in 1964. Next year marks the centenary of his birth and the twenty-fifth anniversary of his death at the age of seventy-four. Today, he remains the most internationally renowned player in the country’s history.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Daniel Abraham Yanofsky was born in March 1925 in the city of Brody, which was then part of Poland but now belongs to Ukraine. He came to Canada with his parents when he was eight months old. His father took a job as a teacher in a Jewish school in Portage la Prairie, Manitoba, and the family later relocated to Winnipeg’s North End. Young Abe grew up speaking Hebrew and English and showed great aptitude in school. While walking with his father down Main Street one day, he spotted a chess set on sale for a dollar in the window of the People’s Book Store, a Jewish-owned shop that also sold Yiddish books and newspapers. He convinced his father to buy the pieces, along with the paper board, and Abe’s chess career began.

That evening in the kitchen, they played three games; the elder Yanofsky won them all. “The next day we played I scored my first chess victory,” Yanofsky wrote in his autobiography, Chess the Hard Way. “A few more victories gave my father the idea of trying me out on other players and accordingly he took me to the Winnipeg Jewish Chess Club, and after a few visits I found that I could beat some of the players there, too.”

It quickly became clear that there was something exceptional in Yanofsky’s play. He gave a simultaneous exhibition a few months after learning the game, playing six people at once and defeating half of them. When an American master, Isaac Kashdan, came to town to take on several competitors at once, Yanofsky scored a draw. He scored a win for the Manitoba team in its annual match against Minnesota when he was ten. At age eleven, Yanofsky was invited to play at the Canadian National Exhibition in Toronto, where he won twenty-six of twenty-seven games in two events. The “slight, fair-haired lad in knickers,” as the Toronto Star described him, was dubbed a prodigy by the national media.

“Hail, the Conquering Hero Comes,” blared the front-page headline in the Winnipeg Free Press when Yanofsky returned home from his Toronto triumph. Greeting him at the train station were his parents and officials of the Jewish Chess Club. Winnipeg’s “11-year-old chess wizard,” as the Free Press called him, became an object of fascination for the local media. The Winnipeg Tribune commissioned him to write a series of instructional articles.

“How is it I can defeat grown-ups at chess so easily?” he boastfully asked in one of his columns. “First of all I have a good memory. Secondly, I am young and able to think more quickly than an older person whose brain must have stiffened a little, like his legs, as his years mounted; then too my eyes are better — I can see more clearly and take in the whole board more quickly than one older.”

Yanofsky’s father limited his son’s chess playing in the early years to Saturday and Sunday so as not to interfere with his school work. They visited the chess club once a week, and Abe later wrote in Chess the Hard Way that he supplemented that practice by getting a chess book. By contrast, young chess players today often have professional coaches and spend hours a day studying opening theory and strategy, aided by computer databases of games and openings. Before long, Yanofsky had surpassed all the other players in Manitoba; he was barred from entering the provincial championships in 1942 because no one else would compete.

Advertisement

For Yanofsky, the Buenos Aires tournament was a watershed moment. It was the site of his first great international success, but it came just as Europe’s big powers were beginning a world war. When Hitler invaded Poland on September 1, the tournament was thrown into turmoil. Poland’s allies, the United Kingdom and France, entered the war two days later. The preliminary phase of the event had ended, and the finals were about to begin. But how could the European players shake hands and sit across the chessboard from one another when their countries were at war?

The English team left Argentina immediately. Chess players had a unique role to play in the war effort. Three members of the English squad served at Bletchley Park, the site of a British code-breaking centre during the war.

At an emergency meeting, the other team captains discussed what to do. It was decided that the tournament should continue, although the idea of the German team playing the Polish or French team was too much for anyone to consider. Six matches were cancelled as a result, with equal points assigned to the teams. The outcome of the Olympiad saw Germany finish first and Poland a close second. Some of the European players were Jewish, and many refused to return home after the tournament ended. All five members of the German team chose not to return to Nazi Germany. There were no further chess Olympiads until 1950.

Although Yanofsky didn’t have to worry about his immediate safety, he, too, had to contemplate an uncertain future. Following the Buenos Aires tournament, he was forced to get a job to support his mother and younger brother, since his father had died the previous year. He dropped out of his high school day classes and worked as an office clerk at a fruit wholesaler. He went to night classes from 7:00 p.m. to 10:00 p.m., eventually graduating from high school at the age of sixteen. That didn’t leave much time for studying chess, but his innate ability continued to shine. In 1941, he won the first of his eight Canadian championships and then embarked on a cross-Canada tour, where he played a remarkable 440 games, losing just eight times.

After a two-year stint in the Canadian Navy, Yanofsky came home in 1946 to an invitation to one of the most prestigious chess tournaments ever held. It was an international competition in the Netherlands featuring most of the top players, including Mikhail Botvinnik of the Soviet Union, who was widely considered the best at the time and would officially be named world chess champion in 1948. While he finished with more losses than wins, Yanofsky once again caught the world’s attention by defeating Botvinnik in their encounter.

For the next two years, Yanofsky criss-crossed Europe, playing in tournaments and giving exhibitions. In a continent devastated by war, chess became a way for countries to return to normalcy. He played in Switzerland, Belgium, the Netherlands, Spain, Denmark, England, and Iceland.

He was cementing his reputation as a top tournament player, and the thought inevitably occurred to him that he might make chess his career. But as a child of the Depression, when he shared the same bed with his younger brother, he made a sober assessment of his prospects. Prizes in European tournaments were meagre. His Canadian championships earned him $100 apiece, and even a major U.S. open event netted him just $150.

The Winnipeg Jewish Chess Club had raised the funds to subsidize his travel to national and international events. His mentors at the club, who were his biggest boosters, also urged him to have a career outside the world of chess. All of this affected Yanofsky’s thinking about whether to become a chess professional. “The financial atmosphere was such that if you were going to devote yourself to chess your earning power would be extremely limited, and I recognized that,” he wrote in Chess the Hard Way.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

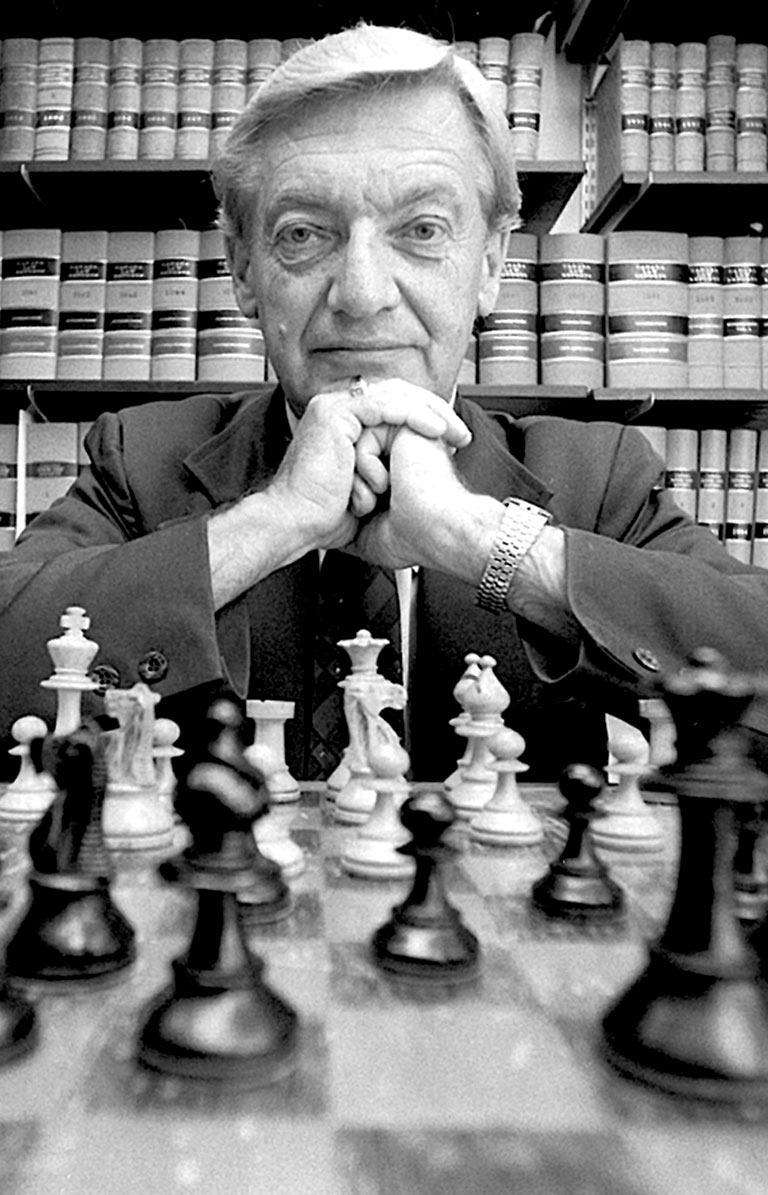

In 1948 Yanofsky returned to Winnipeg and enrolled in law school. He put his passion for chess on pause as he concentrated on his studies, winning several scholarships and accolades for his work, including $1,000 as the top law student in Canada in 1951. He also met a young woman — his future wife, Hilda Gutnik — and after a relationship of nearly four years they were married in 1951. Later that year they moved to England, where Yanofsky began postgraduate studies at the University of Oxford.

Leonard Barden, a long-time Guardian columnist and chess master, shared a flat with the Yanofskys on Abbey Road. He too was a student at Oxford, though in a different college. He remembers Yanofsky as both a first-class honours student and a welcome addition to the chess talent at Oxford. “I never beat him,” Barden said in an interview in 2024, though, he added, “we made some quick draws.”

Oxford ran on the tutorial system, which alternated six weeks of lectures with six weeks off to do research. This allowed Yanofsky to play in tournaments, and the years when he had put his chess career on the back burner during his undergraduate law studies didn’t seem to have adversely affected his play. “In October 1951, we took advantage of [Yanofsky’s] presence in Oxford to organize the first Commonwealth tournament,” Barden said. “It was in term time, so both [Abe] and I sometimes [went] straight from tutorials for the next round.” There were players from England, Scotland, Canada, New Zealand, Australia, and South Africa. Yanofsky went undefeated and finished in second place.

The best test of Yanofsky’s abilities during this period came in 1953, when he entered the fortieth British championship in Hastings, England. In a field of thirty-two players, he got off to a rocky start by losing his first game. But then he found his footing, giving up just one draw and winning nine games in his remaining rounds. His final score of 9.5 points out of a possible 11 was a full point and a half ahead of his nearest competitor. He added the title of British champion to his achievements.

Advertisement

Yanofsky came home after two years at Oxford to start a law practice. This solidified his decision to relegate chess to a secondary place in his life, albeit one to which he returned repeatedly over the years. While he devoted most of his time to his law practice and to a growing career in municipal politics, he represented Canada on many Olympiad teams over the next twenty-five years, turning in credible results every time. He also played in several invitational events, often surprising his younger and more active opponents.

American grandmaster Bobby Fischer, who captured the world championship in 1972, found Yanofsky to be a tenacious fighter. In their first encounter at a major international event in Stockholm in 1962, it took Fischer 112 moves to grind out a win. Their next match in 1968 ended in a draw. Yanofsky’s biggest achievement came at the Tel Aviv Olympiad in 1964, where he scored ten points out of a possible sixteen. That was good enough for the International Chess Federation to award him the title of grandmaster, an elite designation at a time when there were fewer than seventy-five such grandmasters and a long-overdue recognition of his strength in the chess world.

Irwin Lipnowski, an economics professor at the University of Manitoba and a chess master, first met Yanofsky when Lipnowski was eleven and Yanofsky was thirty-two. Yanofsky came to his school to run a chess clinic for the kids. Recognizing Lipnowski’s potential, Yanofsky invited him to play in the 1958 Canadian Open in Winnipeg, driving him to the event every day. It allowed Lipnowski to learn some early and valuable lessons about how to win. Yanofsky advocated “sitting on your hands” before making a move, staying calm and measured, and avoiding impulsive decisions. “He had a very good understanding of colour domination. He knew how to accumulate small advantages,” Lipnowski said in an interview, adding that he put those lessons to use in his own chess career.

Yanofsky had a busy professional and personal life in Winnipeg. By 1958, he and Hilda had two daughters and a son, and his young family and active civil-litigation practice didn’t leave much time for chess. It became even more difficult for Yanofsky to find time to play after he became mayor of the suburb of West Kildonan and, later, a Winnipeg city councillor. Despite all of his other activities and pursuits, chess always mattered to him. To repay the chess community for all the support it had provided to him as a child, he used his connections to organize some international events in the city.

In 1967, a ten-player tournament featuring some of the world’s top talents was held in Winnipeg. It included one of Yanofsky’s long-time favourite players, Paul Keres of the Soviet Union, along with future world champion Boris Spassky and charismatic Danish star Bent Larsen. This was the most prestigious chess tournament Canada had ever held. Yanofsky played in the event as well, and, though he finished out of the running, he won the brilliancy prize for his game against Hungary’s Laszlo Szabo.

Yanofsky retired from Winnipeg’s city council in 1986 and began gradually winding down his law practice. That same year, he made a bid for his ninth Canadian championship. But at sixty-one — as his younger self might have predicted — he found that his reflexes were not as sharp as they had been at sixteen, when he’d won his first Canadian title. Still, he managed to stay in contention throughout and to tie for third place. Though he intended to play more chess in his retirement, health problems intervened. His last tournament was the 1989 Manitoba Open, where he finished second. Though he registered to play in the 1994 Canadian Open in Winnipeg, he withdrew at the last minute.

Suffering from cancer and congestive heart failure, Abe Yanofsky died in March 2000, just twenty days shy of his seventy-fifth birthday. Though he was never a serious contender for the world championship, his legacy in Canada is a lasting one. “He was the man, no question,” Lipnowski said. “He was an inspiration. Everyone in Winnipeg was proud of him.” Had he received the kind of intensive training and mentorship enjoyed by prodigies today, he might have made it to the ranks of the top five players in the world, Lipnowski said.

Though Canada has more than a dozen chess grandmasters today, no homegrown player has managed to garner the kind of international reputation that Yanofsky had at his peak. Nor has there ever been another Canadian child prodigy who translated early achievements into a successful competitive career as an adult. Though some consider Winnipeg an unlikely place to have spawned a prodigy and grandmaster, it’s noteworthy that history’s best player also came from a place without a dominant chess culture. Magnus Carlsen, currently the world’s top player and perhaps the strongest one ever, is from the small town of Tonsberg in Norway. “I know Yanofsky is a legend in Canadian chess,” Carlsen said in an interview. “It is important to have legends.”

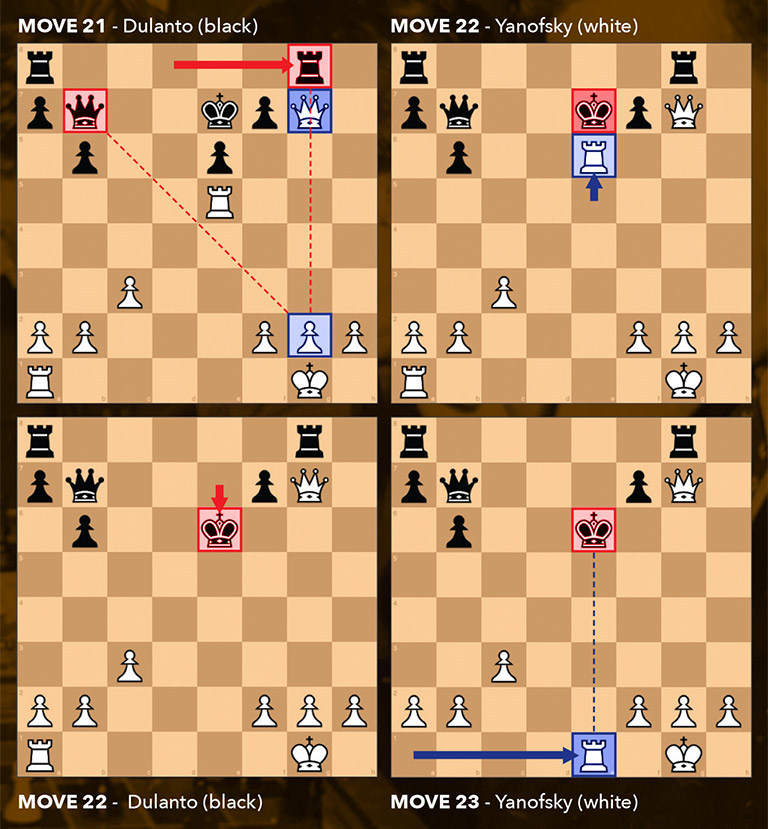

Stroke of Brilliance

Abe Yanofsky appeared doomed in his match against Peruvian champion Alberto Dulanto at the 1939 Chess Olympiad in Buenos Aires, Argentina. But the fourteen-year-old’s flash of inspiration on move 22 allowed him to evade his opponent’s trap and, ultimately, to claim victory.

MOVE 21, DULANTO (top left)

Dulanto moves his rook to threaten Yanofsky’s queen. If Yanofsky’s queen takes the rook, Dulanto will take her with his second rook. If Yanofsky’s queen moves to the left, Dulanto will take her with his king. If she moves to the right, Dulanto will advance his own queen to take the pawn in front of Yanofsky’s king, putting Yanofsky in checkmate. There seems to be no escape for Yanofsky.

MOVE 22, YANOFSKY (top right)

In a surprise move, Yanofsky uses his rook to take the pawn that is guarding Dulanto’s king. This puts Dulanto in check.

MOVE 22, DULANTO (lower left)

To save his king, Dulanto takes Yanofsky’s rook.

MOVE 23, YANOFSKY (lower right)

Now Yanofsky is on the offensive. He moves his remaining rook to put Dulanto’s king in check again. After five more moves, Yanofsky traps Dulanto’s king, and Dulanto resigns.

We hope you will help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement