Measuring Change

“Say goodnight to Fahrenheit,” proclaimed an ad in more than 100 Canadian newspapers on March 31, 1975. Sponsored by the federal government’s Metric Commission, the ad told Canadians that from the next day onward, all temperatures would be measured on the Celsius scale. It also declared that changing from the old imperial and avoirdupois (ounces and pounds) systems to metric would make measurements simpler, more logical and, with 90 per cent of the world using it, keep Canada competitive.

“The easiest way to learn the new temperatures is just to use them,” the ad continued. “Live them. Think them. Talk them. And don’t convert back.”

While proponents saw that April 1st switch to Celsius from Fahrenheit as the start of a glorious new era, others viewed it as an April Fool’s Day joke. Despite the rhetoric promoting the superiority of the metric system, the hope that it would fully replace existing methods of measurement met with resistance. Indeed, as the first major move toward metric marks its 50th anniversary, for a variety of unforeseen reasons, the complete conversion that experts and government officials imagined remains unfinished.

The shift to metric wasn’t sudden — it had been recognized as a backup measurement system in North America since the 19th century. When the Weights and Measures Act of Canada went into effect in 1873, it legally recognized any transactions that involved metric units. By the 1960s, professional associations representing businesses, consumers, educators, scientists and others lobbied the federal government to implement metric. Proponents offered many soon-to-be-familiar arguments, including international standardization, the simplicity of measures based on factors of 10 instead of assorted base numbers and the potential growth of Canadian products in a wider number of markets.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Though detractors insisted Canada could not move forward without American implementation of metric or asked why change something people were familiar with, promoters worried Canadians would be left behind globally. “Canada seems to be asleep,” Leslie (L.E.) Howlett, a National Research Council director and the president of the International Committee for Weights and Measures, observed in 1966. “People are talking about it at times, but nothing is happening.”

Metric advocates closely watched the United Kingdom’s conversion progress, which began in the early 1960s and was scheduled for completion by 1975. Also monitored were major American manufacturers, such as the Ford Motor Company, which studied the effects of metric conversion even though the United States remained the world’s major holdout.

Among the first Canadian adopters, meanwhile, were hospitals, starting with Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children in the mid-1960s. Administrators and hospital associations across the country promoted metric for many reasons, including its widespread scientific use and more precise drug measurements, particularly for younger patients. By 1969, more than 200 hospitals, mostly in Ontario, had switched over. When Calgary’s Foothills Hospital (now Foothills Medical Centre) converted that year, its administrators also cited metric’s use in professional journals, its familiarity among immigrants and new employees, and its increasing presence in commercial and industrial settings. To bring employees up to speed, the hospital offered six weeks of metric-orientation sessions.

Believing metric to be inevitable and desirable, the Department of Industry, Trade and Commerce issued the white paper on metric conversion in Canada in January 1970 to propose a general policy for conversion. The report warned that North America might remain “an inch-pound island in an otherwise metric world — a position which would be in conflict with Canadian industrial and trade interests and commercial policy objectives.” The report also suggested that many adults did not have or forgot the math needed to calculate existing units and that metric would be easier to learn and use.

Though it recognized that full adaptation hinged on American actions, the report concluded that our southern neighbour shouldn’t slow the process. The authors believed that most sectors of Canadian life would have few problems converting as long as the transition was carefully phased in.

The white paper inspired two pieces of legislation that passed in 1971: an amendment to the Weights and Measures Act recognizing the use of metric in Canada; and the Consumer Packaging and Labelling Act, which required metric measurements on most product labels. It also inspired the creation of a preparatory agency that evolved into the Metric Commission. Chaired by former Canadian Pacific Railway executive Stevenson Gossage, it oversaw more than 100 sector committees that monitored and prepared conversion plans for a wide range of interests and industries. There were problems figuring out which sectors should convert fully and which, especially industries reliant on American materials, should take it slowly. The commission dodged questions about the conversion costs, waving them away with a promise that the long-term economic benefits outweighed the price tag.

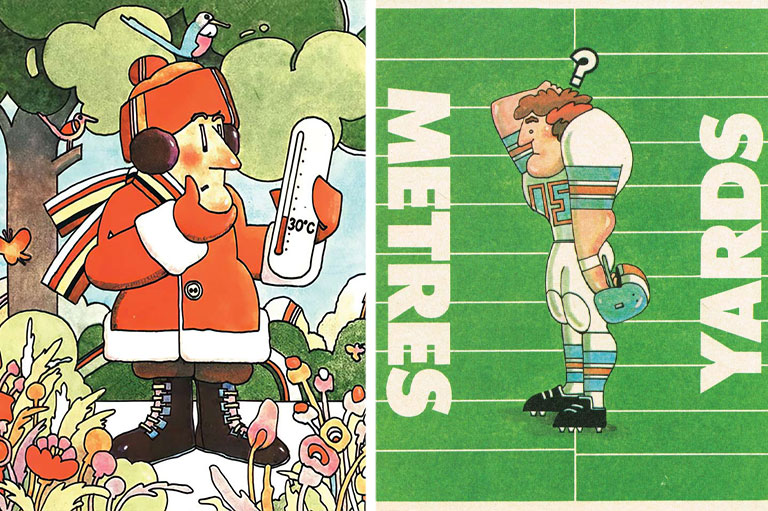

Commissioners believed the process must be gradual and fun — not frightening — for easier public acceptance. Government agencies and major corporations borrowed ideas from the British, such as promotional posters displaying bikini-clad models whose body measurements were provided in both systems. Pulp-and-paper industry giant Domtar Fine Papers Ltd., for example, issued posters featuring “Buffy, the Metric Miss” in 1973 to start public conversations about the problems surrounding conversion. Graphics produced by the commission for newspaper ads and articles about temperature conversions indicated that 30°C was an “ideal day for a swim” while -20°C was “so cold the snow squeaks.”

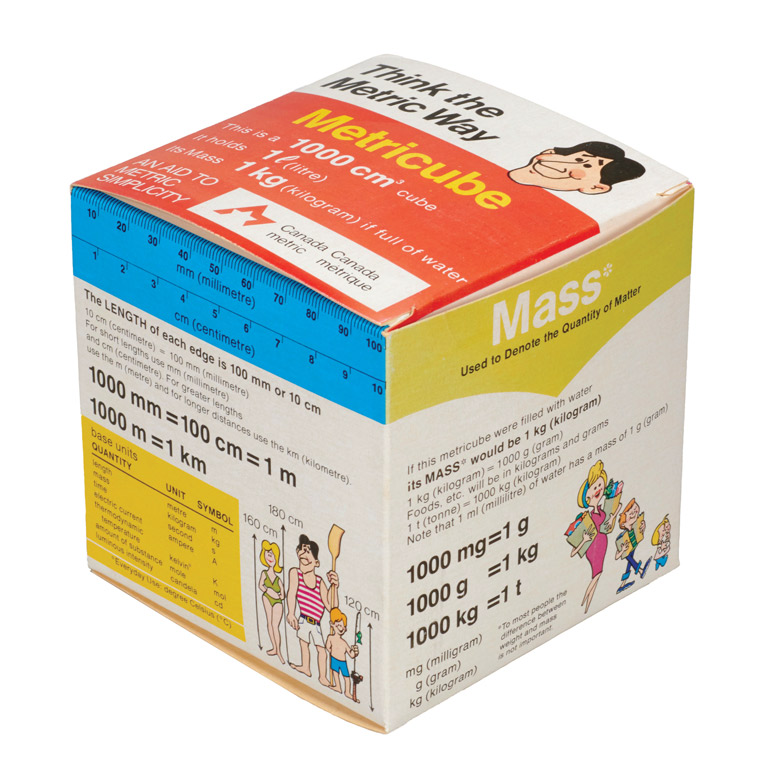

Among the biggest private promoters of metric was pulp-and-paper giant Bowater Canadian Corporation, which worked in tandem with the MacLaren Advertising company to create a colourful series of educational ads published in Maclean’s magazine throughout 1974 and 1975. Bowater claimed that it was the first Canadian company to create “a broad-scale educational program to introduce metrics, especially in areas where the public is initially most likely to be confused,” such as cooking, sports and weather. Other businesses offered handy conversion tools, from promotional thermometers to desk “Metricubes” that listed a range of base metric units on all six sides.

Even professional sports were not immune. The Canadian Football League pondered its future, including possible changes to field length and increasing the number of downs to four to meet metric standards. League officials wondered if yardsticks would eventually become “metresticks.”

Implementing the system in schools was inconsistent. While the Metric Commission reached agreements with the provinces to start teaching metric to primary students in fall 1974, some jurisdictions, including many school boards in Ontario, jumped the gun and began instruction a year earlier, while others, such as New Brunswick, took their time. Textbook publishers struggled as inconsistent timelines left them unable to predict when to publish new editions.

Advertisement

Commissioners believed the process must be gradual and fun — not frightening — for easier public acceptance.

As the guidelines around teaching metric were developed, individual schools took creative approaches. At West Humber Junior School in Etobicoke, Ont., principal Fred Willson turned an unused classroom into a space students named “Metric Mansion.” They sang songs about metric (including a version of “If You’re Happy and You Know It,” which declared “the metric system puts you far ahead”), played games and learned to use tools like metric rulers. The students were convinced to “think metric” instead of learning how to convert from the old measurements.

Adults were harder to convince. The construction industry resisted due to its reliance on American-produced materials. The paper industry was reluctant to shift away from standard North American sizes due to the costs of converting printing presses and the relatively low use of metric paper sizes elsewhere. Despite the encouragement of home economists, people vowed to hang on to their old measuring cups and spoons. Newspapers were filled with cranky columns and letters to editors. Toronto Star columnist Dennis Braithwaite, who admitted he didn’t like change of any kind, was unhappy when weather forecasts started to give temperatures in Celsius instead of Fahrenheit. He called the new temperature scale a “Judas goat” that would lead Canada into the “darkening morass of the metric system.” An editorial in B.C.’s Quesnel Cariboo Observer called metric conversion “a diabolical plot perpetrated many years ago by men of science.” The writer believed that the best piece of advice for Canadians was to “forget everything you’ve ever learned about measurement up to now.”

The Metric Commission’s plan was for Environment Canada to issue its forecasts in Celsius only on April 1, 1975, leaving it to media outlets to decide if they also wanted to include Fahrenheit readings. At least one American television station that also served a Canadian market, WCAX in Burlington, Vt. (which was seen in Montreal), decided to include Celsius in its forecasts.

A major hiccup occurred when Environment Canada did not ship new thermometers to weather stations in time for the conversion. Media reports quoted an unnamed agency official who suggested it was a money-saving move, and existing $10 instruments would be replaced as they broke. Environment Canada quickly changed the story, with Toronto-based service administrator Roy Lee claiming that orders for 10,000 thermometers were placed two years earlier, but only 2,000 had arrived, and required extensive calibration before being approved for use. It was expected all of the old thermometers would be replaced within nine months.

Despite the encouragement of home economists, people vowed to hang on to their old measuring cups and spoons.

Weather offices also dealt with angry or confused calls from the public. “Canadians value their weather information,” Nancy Cutler, metric conversion coordinator for the Atmospheric Environment Service, recalled in a 2015 Toronto Star interview, “and when you start tampering with it, you’re tampering with something very close to their hearts.”

While many living close to the border increasingly relied on American stations to provide temperatures in Fahrenheit, Canadians generally adapted quickly to Celsius and, from the fall of 1975, measuring precipitation in metric.

The metric rollout continued for the rest of the decade. Road signs switched to kilometres for speed and distance in December 1977, while gas stations dropped gallons for litres in January 1979. The conversion of grocery store weigh scales became a political football, with cutoff dates continually pushed off until, in December 1983, stores could only sell items in grams and kilograms.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

During the early 1980s, debates over metric turned partisan, with Liberals for mandatory conversions and Progressive Conservatives against. An anti-metric petition created by the Toronto Sun gathered tens of thousands of signatures. Progressive Conservative MPs brought several anti-metric petitions into the House of Commons in April 1982, including a 135,000-name one that was 5.6 kilometres long and weighed 112 kilograms. Anti-metric groups with names such as Measure Canada and HUMBUG (Help Undo Metrication, Bug your MP) formed. Fields such as real estate continued to hold out. In 1985, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney’s government relaxed restrictions on using the old measurements in areas from food scales in small businesses to home furnishings — as long as metric was also used. His government also dissolved the Metric Commission.

In the long run, not all Canadians embraced the “beautiful logic inherent in the metric system” that the 1974 guidebook “Canada Goes Metric” gushed about. The current federal government acknowledges that some Canadians are more comfortable with the old measurements and allows both to be used. Celsius is the standard for weather, but we still use Fahrenheit to cook. Eyebrows twitch when people are asked for their height in centimetres instead of feet and inches. Outsiders may be confused by our refusal to stick to one system or another, but nobody is rushing to change the temperature.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement