Any Sound You Can Imagine

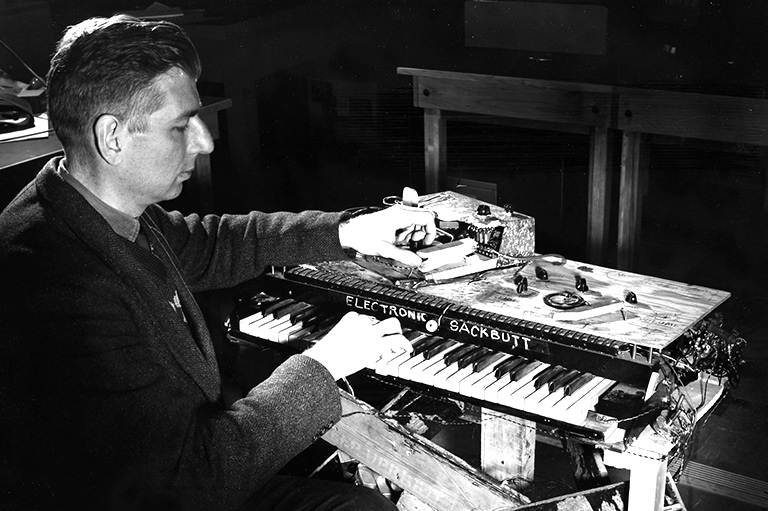

It was a breakthrough. In 1948, Canadian inventor and composer Hugh Le Caine — a physicist at National Research Council Canada (NRC) — finished a prototype of the keyboard instrument he’d been building since 1945 in his personal studio near Ottawa. He called it the electronic sackbut, a reference to a largely abandoned precursor to the trombone, and it’s widely considered to be the world’s first voltage-controlled synthesizer.

Not only could Le Caine now make the “beautiful sounds” he’d dreamed of since he was a kid but others, he hoped, would be able to use his creation to do so, too. While in the end few got to play it, his sackbut remains influential.

To understand Le Caine’s legacy, Tom Everrett, Rowan Nicola and Ezra Teboul, researchers at Ingenium, Canada’s museums of science and innovation, have spent years recreating a fully functioning electronic sackbut. Canada’s History’s senior editor, Alex Mlynek, spoke with Everrett, Ingenium’s curator of communication technologies, to learn what makes the instrument so special.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Why did you decide to reconstruct the electronic sackbut?

We’d hit a wall in our understanding of the instrument. When we acquired it in 1975, the last known time it was played was in 1954; since then, it’s sat in storage or in a display case. Gayle Young’s 1989 book on Hugh Le Caine [The Sackbut Blues] gave us greater insight into the instrument. But we needed to be able to play it to understand what most of the controls did, how exactly it was wired, what its limits were, what its affordances were.

What was your first step?

We sent it to the National Music Centre in Calgary in 2015, where their audio tech, John Leimseider, worked on it to draw schematics so we would understand the electronics design. But there were limits to what he could do without taking things apart.

It came back to us in 2016 with a partial schematic. We put it on display in the new Science and Technology Museum, then revisited the project in late 2019. We determined that to make the electronics work, we’d have to gut the internal controls. This is 1940s electronics; there were many issues. So, we couldn’t restore it. We thought, “If we can’t restore it, why don’t we build a reconstruction?” That allowed us to test our theories about what the different controls did.

We’ve spent almost five years methodically rebuilding this instrument in a nearly identical form, so we’re embarking on the performance aspect to better understand it.

How has it felt to steward the reconstruction?

Exciting. It’s an extremely important piece of Canada’s musical history, and it’s an object that the world should know about. But if you look at histories of electronic music or histories of the synthesizer, it’s still not coming up.

Advertisement

Why was the instrument important?

Le Caine built the electronic sackbut at his home. He demonstrated it to some of his colleagues at the National Research Council here in Ottawa, and the NRC gave him a lab called the Electronic Music Lab.

They wanted him to design, build and test electronic instruments full time. And he provided composers and professors in Canada with them so they could develop the art of electronic music in a research and performance setting. Through that lab, he helped establish, outfit and produce instruments for the first electronic-music studios in Canada at the University of Toronto, McGill University and Queen’s University.

Le Caine also taught and published on the subject, and there’s evidence of influence with other sort-of-early people like Bob Moog in Ithaca, N.Y., who has become maybe the most famous early synthesizer designer. So, Le Caine was connected to most of the key players and the early evolution of electronic music in the mid- to late 20th century.

We’re trying to understand what this instrument is. Is it a quirky electronic instrument? Is it a synthesizer? If it is a synthesizer, is it the world’s first? Is it the oldest surviving? What are the connections to Moog? What are the connections to the Canadian electronic-music scene? We also want to learn how to speak about what Le Caine and the electronic sackbut’s place in history is in a way that people can connect with.

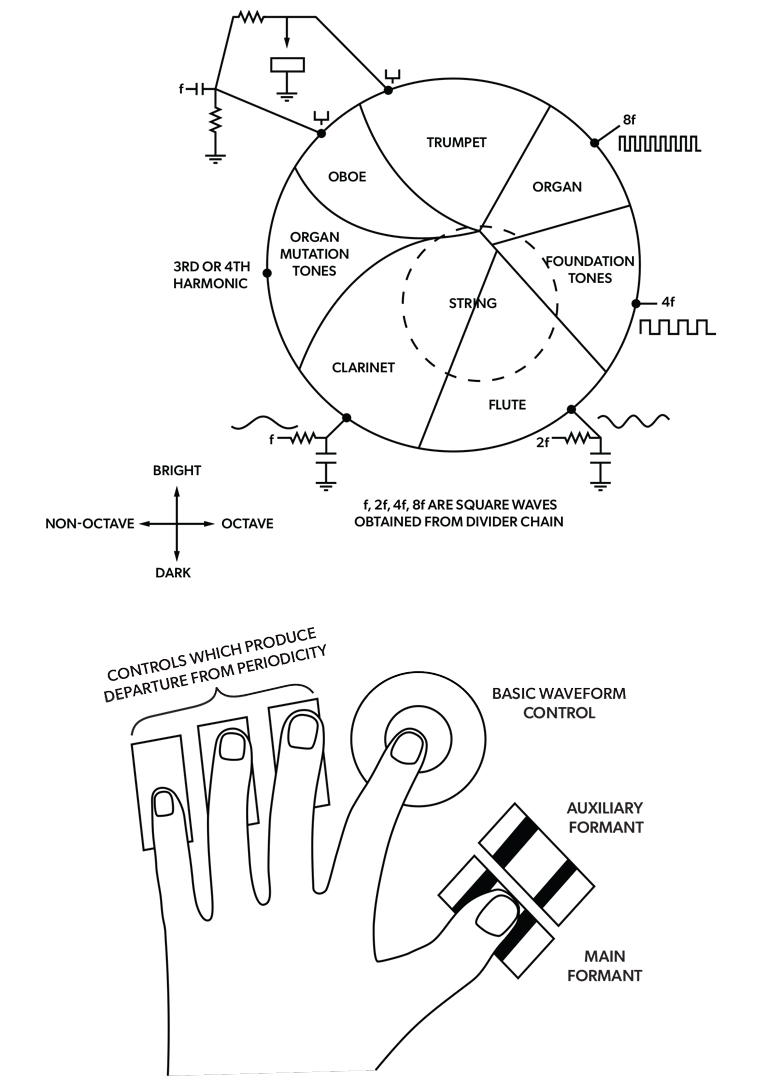

In layperson’s terms, how does the electronic sackbut work?

It’s designed to generate an electronic waveform, then apply complex changes to that waveform so that the resulting sound can be as conventional — a mimicking of classical musical instruments, for example — or as experimental, noisy or subtle and textured as you like.

What’s it like to play?

It can be very easy to play if you just want to have fun, but it can also be extraordinarily difficult to create the recordings that Le Caine produced. It’s also a finicky instrument, and we now understand why he didn’t perform with it.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Hear the wonderful sounds of the electronic sackbut and more early electronic music below...

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Listening Skills

There are several adjectives you could use to describe Gayle Young. Composer, instrument designer, musician, cherished and influential member of Canada’s experimental-music scene would all fit the bill. But it’s her role as a writer that’s helped the world understand the contributions of Canada’s Hugh Le Caine.

Young’s book The Sackbut Blues: Hugh Le Caine, Pioneer in Electronic Music, published in 1989 by the National Museum of Science and Technology, tells the story of Le Caine and how he helped develop the country’s electronic-music community through his innovations and enthusiasm. Young, who’s based in Grimsby, Ont., was inspired to write it after listening to tapes of interviews with people who worked with Le Caine to develop instruments. Initially, her goal was to preserve those instruments, but she soon learned there was a story to tell.

Not only has Young contributed to a deeper understanding of who Le Caine was and what he and his colleagues did but she’s also one of the few people who’ve played the reconstructed version of his electronic sackbut. (She has even recorded a performance, with the help of the team from Ingenium and musician and producer Mike Dubue.) “It’s a bit of a learning curve,” she says. “It feels like there are so many things you could do all at once, but you can’t really concentrate on doing them all at once, especially when you’re not familiar with the keyboard. It requires a lot of attention to sound, a very intense listening.” Luckily, that’s another one of Young’s incredible abilities.

Synthesizing Hugh Le Caine

As a kid growing up in what was then called Port Arthur (now Thunder Bay), Ont., Hugh Le Caine was known as an inventor, a skill he got from his electrical engineer dad, Hubert. “His father worked in the grain elevators there and was very good at fixing things,” says Le Caine’s biographer Gayle Young. “The joke I was told was that when Le Caine Sr. finally retired, staff said, ‘OK, we can finally buy some new gear.’ I think young Hugh picked up the habit.”

Early on, one of those inventions was designed to get him out of a chore. “The family had one of those almost-automatic washers, but somebody had to move the lever back and forth to make the water swish,” says Young. “Hugh’s job was to make the water swish.” His mother, Susan, left him to get the washing done, but when she returned, Hugh was gone. Instead, she found this machine set up and plugged into the wall, swishing the washing on its own.

Born in 1914, Le Caine was also an accomplished musician, thanks to his mom, and played the piano and the violin. As early as high school, notes Young, he dreamt of combining his passions to invent musical instruments.

After studying applied science and physical engineering at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ont., Le Caine got a job developing radar systems for the Second World War effort at National Research Council Canada in March 1940. He’d work there for the rest of his career, with a break to earn a PhD in physics from the University of Birmingham in the U.K.

Le Caine never stopped playing and writing music. He hosted jam sessions with friends and colleagues after work, and he enjoyed photography and riding motorcycles. He was also apparently really funny, says Young, and his musical compositions were quite playful.

Experts like Tom Everrett, curator of communication technologies at Ingenium, marvel at Le Caine’s creativity and ability to innovate. “To be able to develop these things that have become standard in synthesizers as we know them today — they didn’t exist at that time,” he says. “It was the 1940s, 20 years before Moog synthesizers, so he was using really old electronics tech. To be able to think of these things and execute them on that level to create so much expressivity in an electronic instrument is extraordinary.”

In the end, Le Caine invented more than 20 unique instruments, most of which, Everrett notes, are part of Ingenium’s collection. Le Caine retired in 1974 and died of a stroke in 1977, a year after crashing his motorcycle. The Queen’s music school’s building is named Harrison-LeCaine Hall, in honour of its musical and imaginative alumnus.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement