No Votes for Men!

Grade Levels: 5/6, 7/8

Subject Area: Social Studies/History/ELA/Civics

This lesson plan is inspired by the article “No Votes for Men!” in the Great Canadian Women issue of Kayak: Canada’s History Magazine for Kids and the History Bits video “No Votes for Men!”

Lesson Overview

In this lesson students encounter an important step towards the full enfranchisement of Canadian citizens. They explore how social movements can use humour to make change by studying the 1914 Mock Parliament in Winnipeg. Finally, they analyze both the continuity and change in societal attitudes towards gender roles.

Time Required

3-5 class periods

Historical Thinking Concept(s)

- Establish historical significance

- Use primary source evidence

- Identify continuity and change

- Analyze cause and consequence

- Take historical perspectives

Learning Outcomes

Student will:

- Encounter this event as an important step on the journey to full enfranchisement of citizens in our society.

- Explore one example of how social movements can use humour to enlarge citizens’ ethical dimensions and make change.

- Reflect on the continuity and changes in how society views gender roles.

Background Information

The diversity of Indigenous cultures in North America was reflected throughout their many governance systems prior to European colonization. Most Indigenous societies had some form of gender balance, where men and women held different, yet complementary roles.

Through these roles, Indigenous women held positions of power and leadership. The Haudenosaunee, for example, follow a matrilineal structure with women holding leadership roles within the clan.

In the early years of British colonization, some women who owned property could vote. By 1851, however, women were officially excluded from all legislative elections in British North America.

In 1853, Mary Ann Shadd Cary, a Black abolitionist who edited The Provincial Freeman, made one of the first links between gender and racial equality as fundamental human rights.

Between the 1870s and the 1914 Mock Parliament, there were many efforts by women, men and diverse organizations across the country to expand the franchise in different levels of government.

Efforts were also made by organizations representing different interests like the Knights of Labour (1886) and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (1892-1897), as well as the International Council of Women who, at a 1909 meeting in Toronto, resolved in favour of women’s suffrage in every country with a representative democracy. Regardless, it still took years to achieve their aims.

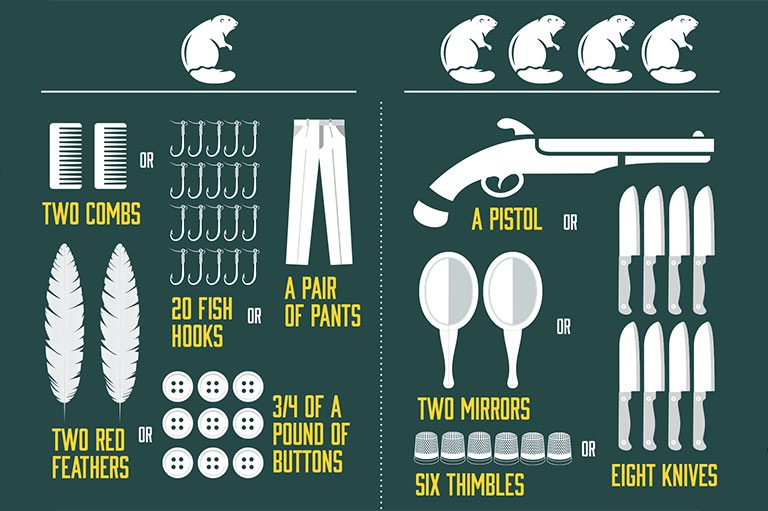

“Mock parliaments” were used particularly by Canadians as a humorous form of protest, a way to encourage public acceptance towards the idea of female suffrage, and to raise money.

The first one was held on February 9, 1893 in Winnipeg, led by Dr. Amelia Yeomans and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union after their petition for suffrage was ignored by the provincial government.

It was followed by at least seven in Ontario, two in British Columbia and four in Manitoba. The most famous — both for its hilarity and eventual impact — was held on 28 January 1914 at the Walker Theatre in Winnipeg.

This mock parliament was organized by the Manitoba Political Equality League (1912-1916), which included members of the Canadian Women’s Press Club and many of Canada’s most well-known suffragists, including Nellie McClung. The group filled the 1,800-seat theatre and sold out two performances and others elsewhere in the province, raising money for the cause, laughter to the rafters, and changing minds in the process.

The following year, Manitoba men voted a Liberal leader, Tobias Norris, whose government enacted female suffrage on January 28, 1916. While occasionally suffering setbacks, the push for voting equality could no longer be stopped.

The Lesson Activity

Activating: How will students be prepared for learning?

1. Brainstorming actions to make change

- Using a ‘think-pair-share’ format, ask students to brainstorm what actions they can take when they want to affect change in a peaceful way. Have them fill out their answers in a chart. (BLM #1)

- Possible answers are:

- At home: Talk to your parents or guardians; offer an action in exchange for something; persuade family members of your reasons and make a vote

- At school: Talk to the teacher or principal; make a proposal through the student or parent council; start a petition; use social media to influence others by presenting a problem and suggesting a solution

- In society: Get the community involved; start a petition; join an organization; write a letter to the editor or an appropriate political body; protest march; refusal to participate; use of social media by highlighting the problem to influence the community; vote for a change of leaders; (riot, rebellion, revolution are all non-peaceful examples)

- Focus in on the VOTE as one of many democratic ways of expressing your opinion and creating change, whether in the home, in the classroom or in society.

- An extension could be to take the chart home and interview family members about which ways of protesting they have used in their lifetime. Share the data about these oral histories in class.

2. In groups, have students research the definitions of the following terms in preparation for the next lessons: enfranchise, franchise, suffrage, suffragist, suffragette. Share and post an anchor chart with these definitions.

Acquiring: What strategies facilitate learning for groups and individuals?

1. Whole class simulation: A Journey to the Democratic Vote in Canada

- Note that gaining the right to vote was not always democratic in the way that we understand it today as including ALL citizens in our society. Rather, it was only applied for some. Genders, racial groups and non-land owners (the poorer economic class) were disenfranchised at different times in our history and at different levels of government.

- Using your students and classroom as a stand in for “society”, take the class through the simulation, A Journey to the Democratic Vote in Canada (BLM #2A)

- Arrange chairs in a circle. This will allow students to see each other as they work through the simulation.

- Each student should randomly select 3 ‘Citizen Identity’ cards which correspond to: Location, Gender, Racialized Ancestry. (BLM #2B) Increase or decrease the number of cards (20 are included) in order to keep the proportions where the class is split into 10 ‘provinces’ and 2 territories with as equal a male/female split as possible.

- Write a timeline on the board, stretching it equally from 1800 to present day, with an arrow stretching in both directions, indicating the past and future. Write “Gains the Vote” above the line, and “Loses the Vote” below the line. This can also be done virtually using a Word document and screen sharing to track those that gain and lose the vote.

- As the teacher or student reads the script, move along the timeline and leave a checkmark above the line when someone gains enfranchisement, and below the line when someone loses it.

- Standing indicates that your voice and your vote count. In a virtual setting, ask your students to toggle their cameras on and off, on indicating your voice and your vote count.

- After the simulation, ask all students to sit (or turn their cameras back on). Post these leading questions on the blackboard. Give students a few minutes to think. Using a talking stick, go respectfully around the circle and give each student the opportunity to respond to one of the following questions (you could post these questions in the chat feature and ask students to respond there as well):

- What did you observe about the voting history in our country?

- What surprised you?

- What do you think were the factors that led citizens to NOT be allowed suffrage, or to be allowed it?

- How did you feel during the simulation when you were given the vote or had the vote taken away?

- How did you feel when you noticed other citizens had experiences different from yours?

- Have each student write an Exit card describing how they felt and what they learned during the simulation.

2. Taking Action for the Vote: A Four Corners Activity

- Protesting for the vote for any of these groups required resolve and actions which would both change the minds of the public and thus, the people in power.

- The following are four different actions taken on the journey to getting the vote for women:

- International Protest March

- Submitting Bills supporting the vote for women in the provincial legislatures.

- International Council of Women passes a resolution that every country with a democratic representative government should include women voters.

- Have a ‘Mock Parliament’ where activists flip the roles of men and women, humorously pretending it is men who want, and can’t get, the vote.

- Write each of these actions: International Protest March, International Resolution, Submitting Bills, Dramatization of a Mock Parliament, on separate, large pieces of paper and post them in each corner of your classroom for a four corners activity. This could also be done through breakout rooms.

- Ask your students: Which action do you think would be most effective in achieving the franchise for women?

- Students go to the corner (or breakout room) they think would be most effective. Once there, they discuss why they think this would be the most effective change agent.

- Each group briefly presents their rationale to the class.

- After the presentations, reveal the dates and outcomes of each action (BLM #3)

- Emphasize that all the actions played a role, but it was the humorous dramatization of a Mock Parliament that changed the minds of male citizens and encouraged them to vote for a provincial government that passed the first law permitting voting rights for women, not only in all of Canada, but in the British Empire. Women in Manitoba were officially enfranchised on January 28, 1915.

3. No Votes for Men! Using Humour to Make Change

- Watch the History Bits video “No Votes for Men!” as a class. Alternatively, you may provide hard or digital copies of the article “No Votes for Men!” found in the Great Canadian Women issue of Kayak: Canada’s History Magazine for Kids.

- Introduce the context of the suffragists by reviewing the four dates in the previous activity.

- Have students read the text independently and discuss what they noticed about the Mock Parliament.

- Engage in a second, closer reading through a “Readers Theatre.”

- Select students to “read” for the class as the roles of Nellie McClung, Frances Graham (Farm Journalist), Genevieve Lipsett-Skinner (Political Journalist) and Rodmond Robbin (Provincial Premier), while the others listen and read along. There are also 2 brief roles for male actors in the play. The class can play the role of the audience who participate by laughing, clapping or booing. Repeat for enjoyment and expression, if desired.

- To view an additional dramatization of the mock parliament, watch the Heritage Minute of Nellie McClung portraying the role of Manitoba’s premier.

- Engage your students in a group discussion:

- Discuss the audience’s reaction to the play.

- How did this play change the public perception of women as being “worthy” and “ready” for the vote?

- Where else do you see humour as being an effective mode of communication and protest? (Example: The CBC program, “This hour has 22 minutes” also uses humour to protest or point out social situations.)

Applying: How will students demonstrate their understanding?

1. No Votes for Men: Continuity or Change?

- Using quotes from the video or graphic story, have students examine what the Political Equity League’s humorous play reveals about what society thought of women. (BLM #4)

- Working in small groups of 3-4 students, they will then draw from their own experiences and evidence from current events to argue whether each particular attitude expressed can be evidence of continuity or change in attitudes towards women.

- Groups can select the one category they feel has changed the most, or the least, and present their findings to the class.

Extension Activity

- Individual students can use the Continuity or Change chart for support to write a persuasive paper answering the question posed by the lesson, “ Where has there been the most continuity or the most change towards equality for women in the last 100 years?”

- Select a current issue regarding equality in society. Define the issue. Design a protest which humorously communicates your point. Lead it!

Materials/Resources:

- History Bits video “No Votes for Men!” or copies of the “No Votes for Men!” article in the Great Canadian Women issue of Kayak: Canada’s History Magazine for Kids

- Printed copies of BLM #1: Actions to Make Change (1 per student)

- Chart paper for anchor chart of definitions

- Printed copy of BLM #2A: Simulated Journey to the Democratic Vote (1 per reader)

- Printed copy of BLM #2B: Citizen Identity cards, cut up into piles. (Students select 1 card from each of the 3 piles. Twenty cards are included. Adjust for class numbers.)

- Chalkboard or another digital platform to write timeline on

- Printed copies of BLM #3: Four Corners.

- Printed copies of BLM #4: “No Votes for Men” Continuity or Change (1 per group or 1 per student)

- Internet access

References:

- Women’s Suffrage in Canada Education Guide, Historica Canada

- “Nellie McClung,” The Canadian Encyclopedia

- “Black Voting Rights in Canada,” The Canadian Encyclopedia

- “Women’s Suffrage in Canada,” The Canadian Encyclopedia

- “Clan System,” Haudenosaunee Confederacy

- “Marginalization of Aboriginal Women,” Indigenous Foundations

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement