Wild Rice Harvest

-

Canoes are paddled, more often poled, through the shallow water. John Barber poles his 70-year-old wife, Nancy, into a bay of wild rice.All photos by Fred Morgan

Canoes are paddled, more often poled, through the shallow water. John Barber poles his 70-year-old wife, Nancy, into a bay of wild rice.All photos by Fred Morgan -

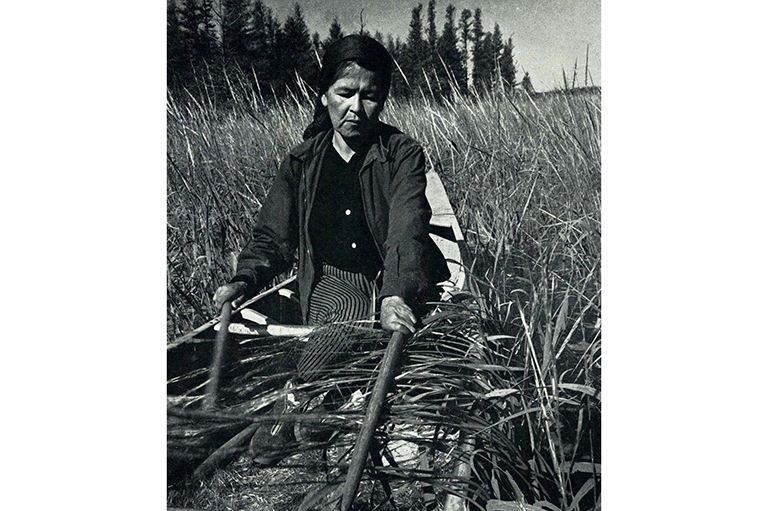

Frances Mike, who has six children, bends rice over the canoe with her left hand and knocks off the grains with three beats of her right. Her sticks keep a steady rhythm as she alternates from one side to the other. The light, tapered sticks are made from birch.

Frances Mike, who has six children, bends rice over the canoe with her left hand and knocks off the grains with three beats of her right. Her sticks keep a steady rhythm as she alternates from one side to the other. The light, tapered sticks are made from birch. -

Where the rice is thinner, Charles Belille rests his pole and paddles slowly. Unlike most of the Court Oreilles hand of Ojibwa, he wears his hair in traditional braids.

Where the rice is thinner, Charles Belille rests his pole and paddles slowly. Unlike most of the Court Oreilles hand of Ojibwa, he wears his hair in traditional braids. -

Helma Belille protects her legs and ankles from the barbs and small white inch-worms with a sheet which also catches the rice and later serves to bag it.

Helma Belille protects her legs and ankles from the barbs and small white inch-worms with a sheet which also catches the rice and later serves to bag it. -

The hollow-stemmed wild rice, called menomin by the Ojibwa, grows from three to five feet or more high in water depths of eighteen to twenty-four inches where the bottom is soft, silty mud. As George Coon beats the rice, grains drop in the water, seeding next year’s crop and providing food for migrating ducks. In this manner the Ojibwas have been practising natural conservation for centuries.

The hollow-stemmed wild rice, called menomin by the Ojibwa, grows from three to five feet or more high in water depths of eighteen to twenty-four inches where the bottom is soft, silty mud. As George Coon beats the rice, grains drop in the water, seeding next year’s crop and providing food for migrating ducks. In this manner the Ojibwas have been practising natural conservation for centuries. -

As rice piles up in the canoe it generates heat. John Barber and his grandson, Jerome Mike, loosen the heap.

As rice piles up in the canoe it generates heat. John Barber and his grandson, Jerome Mike, loosen the heap. -

David Thompson, watching the ricing in 1798, said a canoe held from ten to twelve bushels and it was so plentiful a man could fill his canoe three times a day, with pauses to smoke a pipe and sing a song between loads.

David Thompson, watching the ricing in 1798, said a canoe held from ten to twelve bushels and it was so plentiful a man could fill his canoe three times a day, with pauses to smoke a pipe and sing a song between loads. -

Jerome and his grandfather fill 70-pound bags from their canoe-full. Each canoe could make about $50 a day at 45 cents a pound for green rice.

Jerome and his grandfather fill 70-pound bags from their canoe-full. Each canoe could make about $50 a day at 45 cents a pound for green rice. -

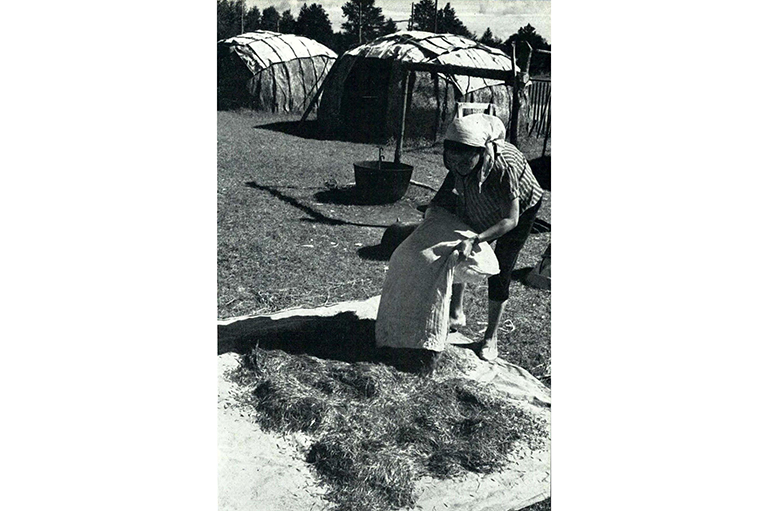

Though most rice is sold green for commercial processing, some is taken to the summer village for treatment in the traditional way. It is spread out on canvases to dry in the sun while women begin parching the 500 pounds collected the previous day.

Though most rice is sold green for commercial processing, some is taken to the summer village for treatment in the traditional way. It is spread out on canvases to dry in the sun while women begin parching the 500 pounds collected the previous day. -

In the village a canvas tipi mixes with Ojibwa wigwams, these ones elm-bark covered, and a birch-bark canoe.

In the village a canvas tipi mixes with Ojibwa wigwams, these ones elm-bark covered, and a birch-bark canoe. -

Ida White, 76 years old, keeps the rice moving with her paddle, as it parches in an iron pot. Only ten pounds is dried out at a time, over a small fire, for twenty minutes. The continuous stirring all day long is tiring work.

Ida White, 76 years old, keeps the rice moving with her paddle, as it parches in an iron pot. Only ten pounds is dried out at a time, over a small fire, for twenty minutes. The continuous stirring all day long is tiring work. -

Paul Wainus, a Menomini, holds the supporting poles as he tramps the parched rice in the time-honoured way to separate husks from grain. New moccasins are the traditional wear for this process.

Paul Wainus, a Menomini, holds the supporting poles as he tramps the parched rice in the time-honoured way to separate husks from grain. New moccasins are the traditional wear for this process. -

Parched rice is tramped in a wooden bucket, set on a skin in a depression in the ground.

Parched rice is tramped in a wooden bucket, set on a skin in a depression in the ground. -

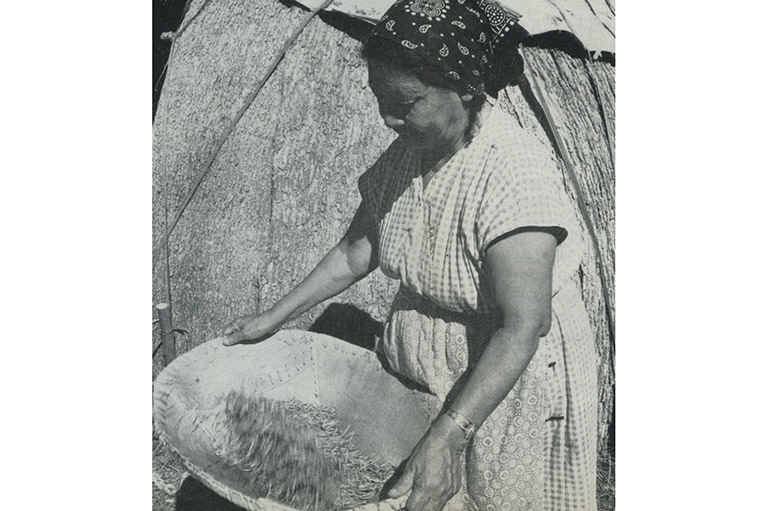

When the rice has been trodden, it is winnowed in a birch-bark basket by Jessie Coon.

When the rice has been trodden, it is winnowed in a birch-bark basket by Jessie Coon. -

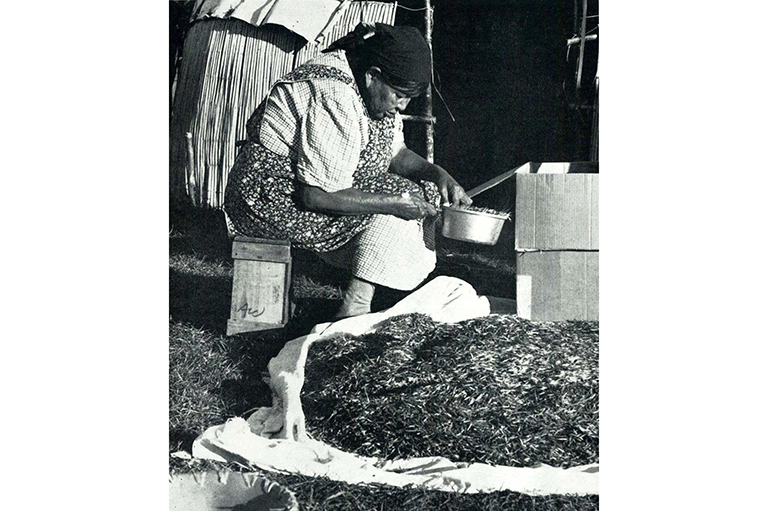

Then comes a final inspection by Nancy Barber, who has gone ricing every autumn in her lifetime. She enjoys the harvesting and the processing, but most of all she enjoys the eating of her favourite food—wild rice.

Then comes a final inspection by Nancy Barber, who has gone ricing every autumn in her lifetime. She enjoys the harvesting and the processing, but most of all she enjoys the eating of her favourite food—wild rice.

In the fall of the year, when the birds are flying south and the trees are gloriously tinted, there comes a time of harvest on the quiet lakes set about the Great Lakes country. Then, in older times, bands of Algonkian and Siouan people would gather to bring in the good grain that rose from the waters.

The wild rice (Zizania aquatica), really a grass, was an important supplement to the meat produced by the hunt, for it could be carried easily and could be kept against the lean times. Not only was it a source of food for indigenous people, it enabled the explorers to extend their journeys, and it was vital to the traders who spread into the country.

They could carry only limited supplies from the east and were it not for wild rice they would have faced starvation before they reached the plains and the buffalo.

Alexander Henry, venturing into the northwest for trade in 1775 admits that “the voyage could not have been prosecuted to its completion” without the supply of wild rice acquired from the indigenous people at Lake of the Woods.

Father Marquette, on his expedition with Joliet in 1673, describes in detail this “sort of grass” growing in small rivers and swampy places which the Indigenous people “Gather and prepare for food in the month of September.” He tells how they shook the ears growing on the hollow stems into their canoes, dried it on a grating over a slow fire, and trod the grain to separate the straw. He also approved of the taste.

How essential this food was to the traders was shown when David Thompson wrote more than a hundred years later of a wintering partner of the North West Company: “Mr. Sayer and his Men passed the whole winter on wild rice and maple sugar, which keeps them alive, but poor in flesh.”

It was, he said; “a weak food, those who live for months on it enjoy good health, are moderately active, but very poor in flesh.” However, he was enthusiastic about the wildfowl that fed upon the rice for they, he wrote, “became very fat and well tasted.” Wildfowl and wild rice are still associated as a tasty dish but they usually arrive separately on the platter.

Daniel Harmon wrote of the wild rice in the waters between Rainy Lake and Lake Winnipeg when he was there in 1804, saying that it constituted a principal article of food at the posts in the vicinity and in ordinary seasons 1,200 to 1,500 bushels of it were purchased annually from the locals.

Although Indigenous people made such use of wild rice, both as food and for its trading value, they would not cultivate it though some people, during the gathering, would wrap a few seeds in clay and throw them into the water. But the Menomini, whose very name proclaims their dependence on wild rice (meno, good; min, a grain, seed) would never sow it for they would never willingly “wound their mother, the earth.”

Today, some Ojibwa still gather along the shore where wild ducks flare out of the waving rice that stands tall in September days. Wild ricing is a significant event to them and they go about it with methods hardly changed from those of their ancestors.

Aluminum canoes may have replaced birch-barks, and iron kettles have taken the place of pottery, but wild rice time otherwise remains very much the same. Not only do they prefer hand-processed rice, but they enjoy the art that prepares good rice, an art that gives the satisfaction it has always given the Ojibwa to work with hands and heart to be sure of a job well done.

The people in the pictures on these pages are from the Lac Court Oreilles reservation, south of the western tip of Lake Superior in northwestern Wisconsin, and most of them are related. Ricing was always a family affair and an occasion for a big gathering.

For many of the older ones, the annual rice harvest is a welcome step into the past, away from civilization back to their youth, camping and sharing the work with their parents. So they are glad when the end of August arrives.

Tamaracks have just begun their alchemy to gold; oaks and maples burn with fire against deep blue sky; an eagle soars above a distant hill of dark pines; best of all, the wild rice is ripe and ready to fall.

One of the ricers, John Barber, described how fifty years ago his family arrived at this same lake early enough in August to build their wigwams for the coming month. Then they paddled out in their canoes and tied clumps of the green rice together to ripen more fully, protected against wind and wildfowl.

This way the rice would grow very large and ripe without falling and John said this made the very best eating. Each family had its own area to tie and harvest and this made gathering easier because ten or fifteen plants held together could all be knocked into the canoe at once. John also remembers the rush bags made by the women to store the finished rice for the winter — a staple food as long as it lasted.

Superstitions developed over the years. Bill Barber remembers a long time ago being told by a medicine woman the rice crop would die because a widow took meat instead of having it served to her when her husband died.

She was right. There was no crop that year; it rotted before it could be harvested. More than once Bill saw prophecies proved true because of somebody’s mistake. (The crop fluctuates considerably, being sensitive to weather and parasitic attack. Canadian production varies from 100,000 pounds to more than a million pounds in a year.)

The Court Oreilles Ojibwa take a fatalistic approach to the prospects of the crop, speaking always of how bad it will be. This stops only when they are in their canoes and the seeds are dropping off the stalks like rain slowly rising up around their feet. Then they are happy and work to their hearts’ content because nature has been good to them, and they will gather and give thanks when all the work is done.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!