Divided Loyalties

I am sorry to say that there has been some trouble in the plains between the hunters and a band of Sioux, in which two [people] from this settlement were killed, and one wounded severely in the knee. The[y] are much excited about this, and I am afraid there will be more fighting hereafter.

On the 3rd instance the English mare died, after a few hours illness ...

Eden Colville,

Lower Fort Garry, 18 Septr, 1850

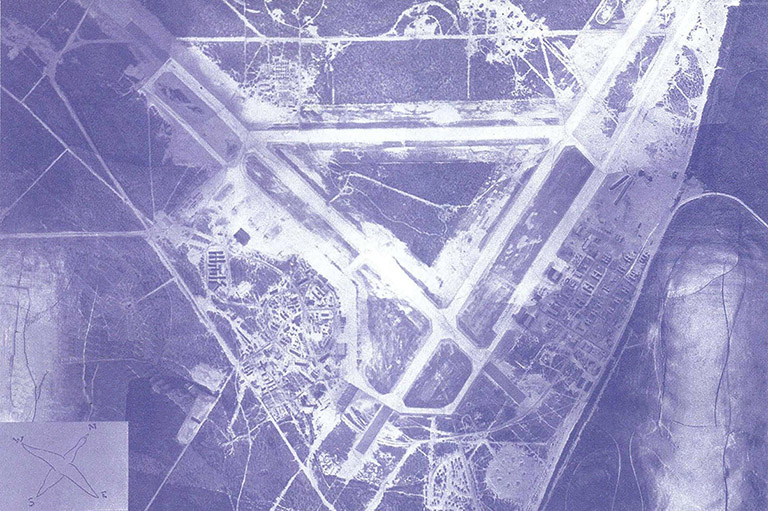

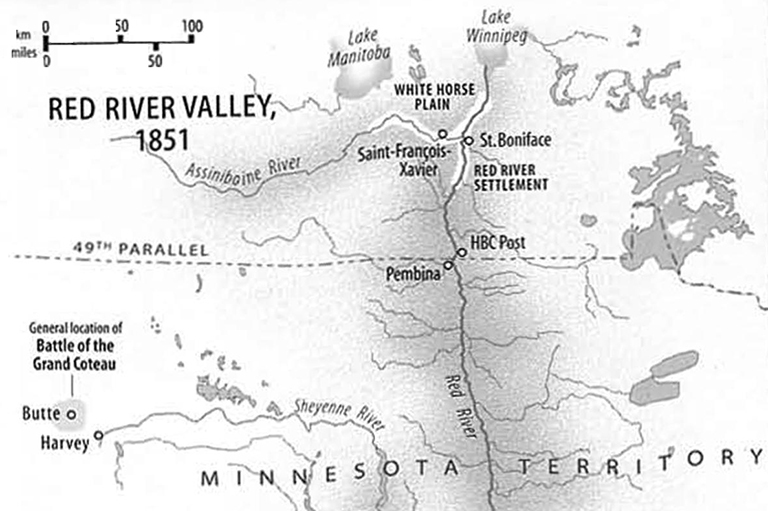

The governor of Rupert’s Land was right: There was, indeed, more fighting the next year between the Métis and the Sioux—the Battle of the Grand Coteau, considered a seminal moment in the history of the Métis people. It occurred in today’s North Dakota, near the headwaters of the Sheyenne River, on the eastern ridge of the Missouri Coteau, the long escarpment that indicates the second steppe of the North American Plains.

It consisted of one evening of preliminaries and two full days of attacks by Sioux fighters on a Métis buffalo-hunting brigade that had travelled south from White Horse Plain, a community centred around the Catholic parish of Saint-François-Xavier, forty kilometres west of present-day Winnipeg.

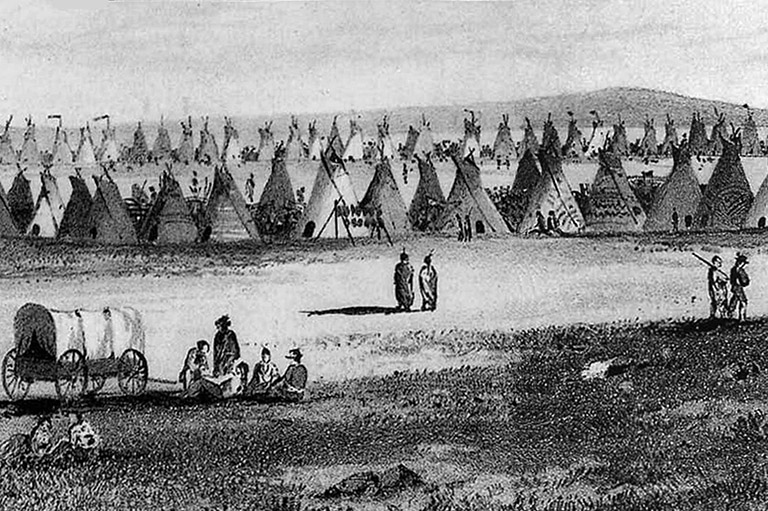

The White Horse Plain brigade was relatively small, consisting of about sixty rifles or hunters along with women and children. They were taking part in a summer ritual, the slaughter of bison, from which they made pemmican, a concoction of buffalo meat and fat that fed the men of the fur-trade boat brigades on their long river journeys during the short northern travel season.

In journeying over the Great Plains south and west of the Red River settlements, they were skirting the borders of territory held by the Sioux, with whom, as the children of Cree and Ojibwa mothers, they maintained an enduring enmity. They were also, as it happens, journeying over an international border.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

That summer, the Métis were aware that the Sioux intended to interfere in their hunt. Late on Saturday, July 12, 1851, that intention was realized. Forewarned by scouts who noted the presence nearby of a large encampment of some twenty-five hundred Sioux, the Métis brigade began a defensive strategy—circling the Red River carts with which they hauled the spoils of the hunt back north to their settlement, digging trenches, and throwing up ramparts.

Through the next day and into the next they repelled successive charges of the much larger Sioux forces. On July 14, the Sioux finally retreated. Not far off, a much larger brigade of Métis—about six hundred rifles—was hunting buffalo. They were Métis from St. Boniface, in the Red River settlement, and from Pembina, in Minnesota Territory.

Arriving as a thundering relief column of mounted riflemen, they, with the mounting casualties and dwindling ammunition supply of the Sioux as well as the deteriorating weather, brought an end to the hostilities. Remarkably, the Métis suffered only one casualty, a scout, “l’infortuné Jean Baptiste Mal à terre” of Saint-François-Xavier parish (see sidebar).

Though the Métis were superb horsemen and disciplined fighters, their decision that summer to hunt in two separate brigades—a White Florse Plain party and a Red River party—was communal folly. Aware that the Sioux intended to harass the hunt, the Métis doubled the risk of a collision between themselves and the Sioux hunters by splitting in two and acting independently of one another.

Beyond calculation, they increased the risk of battle for the smaller brigade if it were intercepted—as it was—by the Sioux. This dangerous decision has perplexed historians. The common conjecture is that the community split over the Hudson’s Bay Company’s prosecution of a Red River Métis for illegally trafficking in furs.1

But evidence suggests that the Métis of the West, by the early nineteenth century conscious of themselves as an independent people, may have been for a time split not by an internecine quarrel but by an imaginary line that had come into being (though not necessarily into force) thirty-three years earlier—the forty-ninth parallel.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, the Métis found themselves increasingly challenged by the flux of events in the Red River community. The arrival of Scottish settlers under Lord Selkirk’s aegis in 1811 had earlier been taken as a direct threat to Métis trade, livelihood, and territorial interests.

The HBC’s trade and administrative monopoly in Red River rankled through the 1830s and 1840s, while eastern Canadian interests in the West began to intensify as Confederation moved from dream to reality. Meanwhile, in 1849 the U.S. solidified its claim on its Upper Midwest frontier when Congress created the Minnesota Territory (which included present-day North and South Dakota).

For many Métis people, the changing political and economic landscape probably raised this question: what allegiances might best serve their interests as a distinct people and preserve their way of life? For the Métis of Pembina in the middle of the nineteenth century, that allegiance appeared to lie with the Americans.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Pembina, 130 kilometres south of the forks of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers, in an area that was part of the original Hudson’s Bay Company grant, was settled by Europeans as early as 1780. But it was abandoned by the HBC in the early 1820s because the 1818 declaration of the forty-ninth parallel as the border placed it within American territory.

Pembina Métis, beholden to the HBC for their livelihood, moved north to White Horse Plain; others settled in St. Boniface. In the 1840s, however, prompted by grievances with the HBC and attracted by new American initiatives, Métis began to migrate back south to Pembina.

In 1844, a Canadian serving with the American Fur Company, Norman Kittson, opened a trading post at Pembina that challenged the HBC monopoly of the fur market in the Red River drainage. Now the Métis (and First Nations) had another buyer for their pelts and the possibility of better prices.

As well, Kittson opened a market for buffalo robes, which the HBC was reluctant to handle. He transformed an embryonic carting connection between Pembina and settlements to the south. All of these provided employment to the Métis.

The next year, the U.S. war department responded to complaints from Kittson, his financial backers, and their political champions in the frontier Upper Midwest about the “annual incursions” of “the British [Métis] of the North Red river.”

It sent a detachment to Minnesota Territory to warn Métis hunters that they were trespassing if they followed the bison south of the forty-ninth parallel. For some Métis who didn’t want themselves excluded from hunting south of the border, this military warning was a further incentive to relocate.

Then, in 1848, Georges-Antoine Belcourt, a Quebec priest who had earlier championed the Métis in their grievances with the HBC and had been banished from Red River, returned west and reinvigorated the mission at Pembina. He became an advocate for U.S. government protection for the Pembina brigade.

In September 1850, he wrote a letter to the first governor of Minnesota Territory, Alexander Ramsey, complaining “of manifold injuries and insults received by the [Pembina Métis] … from the subjects of the British crown, and … the deportment of the agents of the Hudson’s Bay Company.” He claimed that the trespassing hunters from the north would mean a season of “misery’’and “privation” in and around Pembina. In an essay later in the decade, he argued for Minnesota Territory authorities to encourage more Métis emigration from HBC settlements.

In 1850, too, Jean Baptiste Wilkie, a captain of the Pembina buffalo hunt, led a deputation to meet Ramsey, seeking his endorsement of their administration of the Pembina settlement. Ramsey, eager to have good government on the new territory’s northern reaches, was glad to do so.

Also, in an 1850 report, the governor recorded requests from the Métis of Pembina for a government role in the preservation of the buffalo from slaughter by hunters from north of the international boundary:

This people have, upon several occasions … urged the necessity of decisive and preemptory action by government to protect them in their rights as American citizens, and preserve the buffalo … from the trespass of British subjects, who, destroying them in their annual hunts, diminish thereby their means of subsistence.

For the Pembina Métis, the alliance with the Minnesota Territory administration offered the possibility of release from the mercantile governance of the HBC, in which their communal aspirations and apprehensions were no more than incidentals in the company’s pursuit of commercial success (and where the violent death of one of their men in battle shared equal billing with a dead horse in the HBC governor’s account).

For the pioneer administration of Minnesota Territory, which sought to effect the national policy of subduing and “civilizing” First Nations people on agricultural reservations, the alliance with the Métis offered a check on HBC activity south of the international border and the nomadic ways that accompanied the fur trade.

Advertisement

What the White Horse Plain Métis thought precisely of their brethren’s dalliance with the Americans is unknown. But it’s clear that though they and the combined brigade of Métis from Pembina and St. Boniface agreed to form a plan of mutual support in case of Sioux attack, by 1851 each wished to act independently of the other during the summer hunt.

According to Manitoba historian W.L. Morton’s description, they moved in parallel columns, along parallel routes about thirty to fifty kilometres apart. Only when the smaller party was under duress did the larger party ride to the rescue.

Despite the risk, the Métis continued to hunt separately in the years after the Battle of the Grand Coteau. Isaac Ingalls Stevens, commander of a rail-corridor-exploration party dispatched by the U.S. war department and Congress, crossing Minnesota Territory to take up his appointment as governor of Washington Territory in 1853, met with Wilkie and had what he described as a “very pleasant conversation.” He reported that the hunt leader was keen on a permanent U.S. Army presence in the Red River drainage.

I made some inquiries as to their views concerning the establishment of a military post in this vicinity, say at Lake Miniwakan. The suggestion met with their hearty approval, and … Wilkie assured me that were one located there, the people would remove and settle near it, cultivating sufficient land to keep the post supplied with vegetables and provisions.

When the White Horse Plain Métis leaders four days later—on their summer hunt, and again separated from their Pembina brethren—invited Stephens to visit, his attitude was different. Acting as an American officer in the presence of a foreign threat, he ordered his command to move camp and not fraternize with the Métis.

At his meeting, he was cordial, but indicated he would do no more than transmit to the U.S. government the Métis view that they had a right to hunt south of the border.

After Stevens left the Pembina brigade, his command passed a hill, Butte de Morale, nine kilometres northeast of today’s Harvey, North Dakota. “Here occurred an engagement between some [Métis] and Sioux, in which one of the former, by the name of Morale, was killed; hence its name,” Stevens noted in his journal entry for July 18, 1853. Somewhere nearby is the unmarked grave of “l’infortuné Jean Baptiste Mal à terre,” the scout from White Horse Plain killed in the Battle of the Grand Coteau.

The death of the former speaks to the resolute and communal will with which the Métis of the Red River prosecuted their unique contribution to the northern fur trade. The death of the latter speaks to the same resolute will with which some of these same Métis prosecuted another communal purpose, a partnership role in the introduction of American government and opportunity on that country’s northern Great Plains.2

1 In May 1849, Pierre Guillaume Sayer was brought to trial in the General Quarterly Court of Assiniboia on charges of violating the HBC charter by illegally trafficking in furs. While three hundred armed Métis led by Louis Riel père assembled outside, the court found Sayer guilty, but recommended mercy. Sayer was released with no punishment, and the company’s power to enforce its monopoly in Red River was effectively lost. However, Cuthbert Grant, the leader of the White Horse Plain Métis community, who had been appointed warden of the Plains by HBC governor George Simpson, upheld the HBC monopoly at the Sayer trial. In doing so, he alienated other factions within the larger Métis community.

2 The retreat of the fur and pemmican trade before the advance of settlement and steam did not spare the Métis of Pembina from the atomization and dissolution of the other Métis communities of Red River. Their nascent partnership with American territorial and national governments was further impaired by flooding in the Pembina region, which made farming difficult and forced them to relocate westward; by statehood status for Minnesota, which placed Pembina west of the new state’s border and lost the Métis community its territorial champion; and by the U.S. Senate rejection of treaties Minnesota Territory governor Alexander Ramsey made in 1851 with the Ojibwa of Pembina and Red Lake, which denied Pembina residents and territorial authorities the protective federal government presence they sought.

The Battle of the Grand Coteau

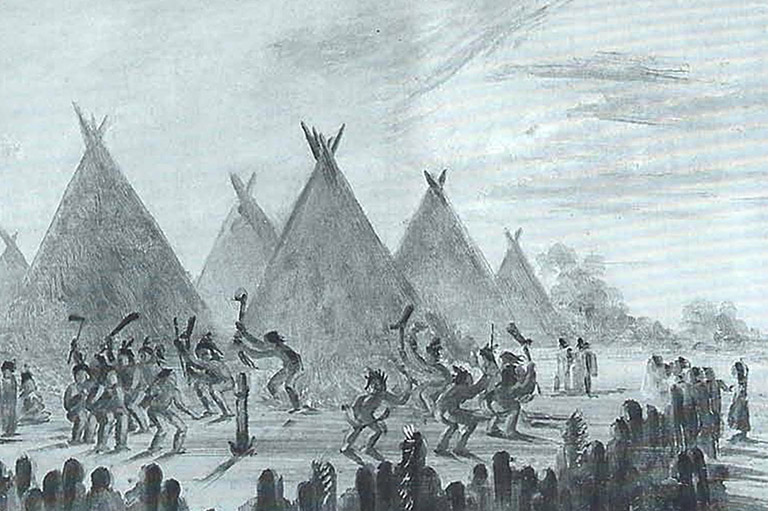

On June 12, 1851. the shadow of the Earth blacked out the moon rising over the prairies. If the eclipse was an omen, it wasn’t for the Métis hunting buffalo in the rolling country of what is today western North Dakota. It was for the Sioux, who would, over the next two days, lose to the Métis in a battle that historian W.L. Morton called “the most remarkable military feat of the ‘new nation’ of the Métis.

The Métis at what became known as the Battle of the Grand Coteau were few, the Sioux many. But the Métis were better equipped than their foes, and with decades of fighting behind them they had developed battle tactics well adapted to the plains environment.

When scouts warned of twenty-five hundred Sioux assembled nearby, the party of Métis from White Horse Plain quickly circled their Red River carts wheel to wheel, shafts in the air, and secured them with the poles used to make frames for drying buffalo meat. Inside this corral, draft animals were protected and women and children sheltered in shallow trenches.

In a ring outside the barricade, men dug rifle pits to keep the Sioux from getting to the carts. The strategy worked. Though the great army of the Sioux initially charged the barrier, then spent hours skirmishing and sniping the first day of battle, a scorching July 13, managing to lob the occasional arrow into the corral, they could not penetrate the Métis defences manned by sixty-seven guns, some of them—like a young Gabriel Dumont—barely teenaged.

After the frustrated Sioux retreated before a sudden thunderstorm, the White Horse Plain Métis made the risky decision to decamp early the next morning to join the much larger Red River Métis brigade hunting nearby. They executed the manoeuvre with finesse.

While scouts kept a lookout, the carts advanced in four columns, which allowed them, at a moment’s notice, to turn and quickly form a barricaded circle. When again, with war cries, the Sioux attacked, the Métis held them off. Five hours of skirmishing later, another thunderstorm broke. As the Sioux galloped away defeated, the first of a party of Red River Métis came pounding over the prairie.

It was the end of the Battle of the Grand Coteau. The combined seven-hundred-man force of Red River hunters and their Ojibway allies was too large for the Sioux to consider another attack. One Métis died. Métis sources claimed eighty Sioux dead.

Defeating such formidable warriors as the Sioux, Morton writes, gave the Métis “mastery of the plains.” But thirty-four years later, similar battle strategies could not secure them a victory over the Canadian militia at Batoche. As for the Sioux, in 1876 they would obliterate General Custer and his cavalry at the Battle of the Little Big Horn.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!