President Harding’s Last Stand

-

A weary President Harding rests at the tee, Shaughnessy Golf Club 1923.Vancouver City Archives

A weary President Harding rests at the tee, Shaughnessy Golf Club 1923.Vancouver City Archives -

The presidential parade passes up Granville Street while thousands cheer.Vancouver City Archives

The presidential parade passes up Granville Street while thousands cheer.Vancouver City Archives -

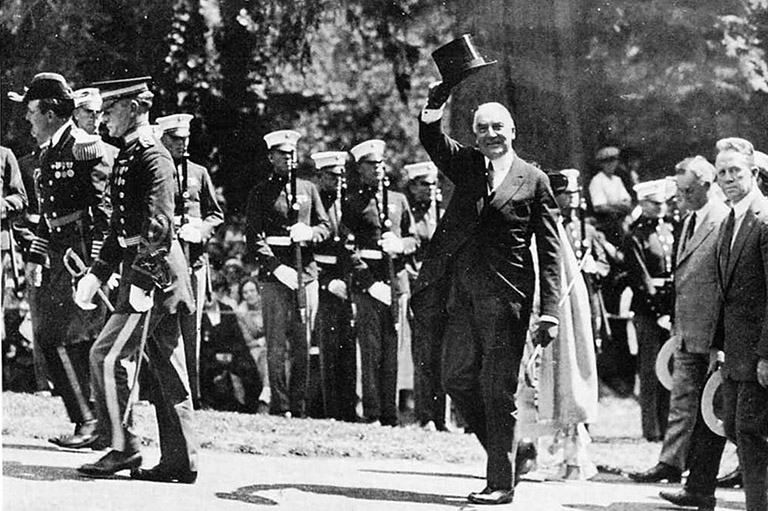

The president is escorted through Stanley Park before his speech.Vancouver City Archives

The president is escorted through Stanley Park before his speech.Vancouver City Archives -

President Harding and Vancouver Mayor Tisdale cool their heads in the summer heat.Vancouver City Archives

President Harding and Vancouver Mayor Tisdale cool their heads in the summer heat.Vancouver City Archives

On a hot summer day in 1923 Warren G. Harding, President of the United States, disembarked from the troop carrier, U.S.S. Henderson onto Vancouver’s Pier A. The band aboard the Henderson played “The Star Spangled Banner” as the President and Mrs. Harding made their way down the gangway.

Once on Canadian soil, a twenty-one gun salute from the 16th Brigade, Canadian Field Artillery shook the air. Along the dock, the president inspected a guard of honour while a Canadian military band picked up the strains of “The Star Spangled Banner”.

A formal welcome was presented by the representatives of the federal, provincial and civic governments. This was the beginning of a historic visit by the twenty-ninth president of the United States. But it was a visit soon followed by tragedy.

In the late spring of 1923 President Harding began a long tour by train through the western United States, followed by a sea voyage to Alaska. On the return journey from the territory, a brief goodwill stop in Vancouver was scheduled.

The first part of his trip was physically taxing on the president. During his swing through the West, he made fourteen formal speeches in the larger cities. The president was a gregarious individual who enjoyed grass roots politicking.

Although the president’s first scheduled stop was not until St. Louis, he frequently halted the train along the way to make impromptu speeches from the rear platform of his specially built rail car. The presidential train crossed Missouri under an unrelenting sun.

Harding’s speeches from the rear platform left him badly sunburned and his lips became so swollen that he had to cancel several engagements in Kansas City. On 4 July the president and his party reached Tacoma, Washington where they boarded the Henderson for the journey to Alaska.

The Alaska trip was intended to give the president a first-hand look at the problems facing the territory. A bureaucratic nightmare needed to be sorted out—five government departments shared administrative responsibility for the territory—before a coherent resource development policy could be achieved. However, those close to Harding hoped the relatively relaxed Alaskan journey would be recuperative.

The president’s health had deteriorated since his inauguration in 1921. Increasingly, he tired on exertion. In early 1923 the fifty-seven year old Harding was stricken with what his physician diagnosed as influenza. He never fully recovered. Harding began to have difficulty breathing while lying down and complained of attacks of indigestion, abdominal pain and an oppressive feeling in his chest.

Despite his warm reception from the residents of Alaska, Harding seemed in low spirits. The sea voyage did not provide the hoped-for improvement in his health and his physical discomfiture was not lessened by a rare Alaskan heat wave. During his visit, the president sweltered under temperatures reaching 96 degrees Fahrenheit.

On 22 July the Henderson headed south from Sitka on her return journey from Alaska. During the trip to Vancouver Harding suffered what his personal physician, Dr. Sawyer, diagnosed as ptomaine poisoning, brought on by eating tainted crab meat. Although physically ill, Harding refused to cancel his visit to Vancouver.

The Henderson steamed into Vancouver Harbour on the morning of 26 July to be greeted by a salute from the six-inch guns of the H.M.S. Curlew. After receiving an official welcome at dock-side, the president drove by motorcade the two miles to Stanley Park.

Thousands of city residents filled the sidewalks to catch a view of the president as he waved to the crowd from his open car. The streets along the parade route were decorated with hundreds of Canadian, British, and American flags. Lamp posts were draped in bunting. Banners stretched between the buildings proclaimed greetings from the citizens of Vancouver.

Sign up for any of our newsletters and be eligible to win one of many book prizes available.

In Stanley Park the president was welcomed by thunderous cheers as he walked from his car to the stage. An audience estimated at over 40,000—one of the best crowds the president received on his entire tour—listened with the aid of a specially installed amplifying system to the president’s formal speech.

President Harding’s Canadian reception seemed to take some American journalists by surprise. As one reporter wrote, “An American observer taking in the frequent outbursts of approval might easily have supposed that a popular candidate for public office in the United States was speaking to an audience of his most ardent supporters.”

Harding’s enthusiastic reception was in large part due to the fact that this was a history-making visit. Harding was the first American president, while in office, to set foot on Canadian soil and the city’s residents turned out in their thousands to witness the event.

As the Vancouver Sun declared, it was to Vancouver’s honour that the American press reported, “... to their readers in every city of the United States that no place on the itinerary has given the president so vast and overwhelmingly cordial a reception as this Canadian city.”

Also, Harding, through his efforts to bring the United States into the World Court, was regarded by many in Canada as a peacemaker. Canadians desired to hear the rhetoric of peace and Harding did not disappoint them.

As thousands of Vancouver citizens crowded around the stage set on a grassy slope in the beautiful park, they listened as Harding proclaimed: “You are not only our neighbor, but a very good neighbor, and we rejoice in your advancement and admire your independence no less sincerely than we value your friendship.” The Vancouver audience enthusiastically received the president’s words.

Yet the energy of the crowd seemed to draw strength out of the president. Harding appeared increasingly frail under the strain of the occasion. For the duration of his speech he had to face the blistering summer sun. After the Stanley Park address, Harding was taken to a luncheon at the old Hotel Vancouver, presented by the Government of British Columbia and the City of Vancouver.

Again cheering crowds lined the street and pressed into the hotel lobby to catch a glimpse of the president. The luncheon was no small affair. Over 600 guests filled the hotel ballroom to listen to an address by Premier John Oliver.

After the lunch Harding was driven to a local club for a golf game. He managed to play out the first few holes, but soon became physically exhausted. After the sixth hole, the president’s foursome moved over and played the eighteenth, so that those watching would not easily suspect they had not nearly completed their game.

Before once more entering his car, Harding summoned sufficient energy to move through the throng of club members and shake hands. Consummate actor that he was, Harding seemed always able to put on a public face. But the Vancouver visit was taking its toll on the man. He returned to his hotel room to rest for an hour before participating in the evening ceremonies.

That evening, at a dinner given him by the Government of Canada, Harding delivered a fifteen-minute speech on the bonds of peace between Canada and the United States. “I am sure,” the president declared, “we share the same fundamental convictions about world peace and the human obligation to promote and maintain it. We may differ as to the practicability or effectiveness of this or that programme, but we are in complete accord about the end to be attained.”

Although, as usual, the Canadians received it enthusiastically, Harding’s speech was delivered without energy or drive. Following dinner, the president attended a public reception. He stood in the receiving line shaking hands for less than half an hour. The line was not nearly finished when the president excused himself and returned to the Henderson.

Save as much as 52% off the cover price! 6 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital.

Shortly after 10 p.m. the Henderson backed away from her dock at Pier A and steamed slowly toward the harbour entrance. Hundreds of cars converged at Brockton and Prospect Points to take a last look at the Henderson and her two destroyer escorts as they passed Stanley Park on their way to Seattle.

The navigation lights on the three ships were now partially obscured by a sea fog which had rolled into the harbour. The ship carrying the president soon disappeared into the gray night. President Warren G. Harding's first and last visit to Canada had come to an end.

During his time in Vancouver, the president had managed to carry out the duties of office—the dinners, the speeches, even a golf game—but the strain was becoming too much. Harding had maintained a brave front during the long tour, but he was very seriously ill and spiritually deeply depressed. In his cabin on the Henderson, the president's night was far from peaceful.

About 3 a.m. the sound of grinding metal filled the fog shrouded night air. As the Henderson’s crew made their way onto the deck it became clear that the president’s ship had struck another vessel, the American destroyer Zeilin, amidships.

There was apparently not much damage to the Henderson and no serious injuries among passengers and crews on either ship, but the Zeilin was in danger of sinking. Harding's valet rushed into the president’s cabin to report that the Henderson had received minor damage, and that the captain had ordered everyone on deck. Harding was lying on his bed with his face in his hands. “I hope the boat sinks,” the president replied.

In Seattle President Harding gave an important speech on the future of Alaska. The president delivered it poorly, at one point confusing “Alaska” with “Nebraska”. As in Vancouver, the heat in Seattle was intense and during the day Harding stood bareheaded in the blazing sun. By the end of the evening the president was near collapse. He was complaining of severe cramps and indigestion.

Harding’s physician continued to blame the president’s illness on ptomaine poisoning, but Harding’s condition seemed more serious to others in the presidential party. Secretary of the Interior Hubert Work, once a practicing physician, and Harding’s medical aide Dr. Joel T. Boone examined the president and found that his heart was considerably enlarged. All tour stops scheduled between Seattle and San Francisco were cancelled.

The presidential train proceeded directly to San Francisco where Harding was moved to the Palace Hotel. On Sunday 29 July Harding’s condition worsened. On Monday and Tuesday the president was given intravenous digitalis and caffeine. By Thursday, Harding seemed much better.

His attending physicians cautiously announced, “While recovery will take some time, we are more confident than heretofore as to the outcome of his illness.” The president sat up in bed and talked briefly about future fishing trips and said he regretted the fact he had caught no fish in Alaska.

As the president’s nurse prepared him for the night, Harding twitched sharply and his mouth fell open. Breathing ceased. The president was pronounced dead at 7:32 p.m. on 2 August 1923.

Coming as it did so soon after his visit, Vancouver residents were deeply shocked by the president’s death. The Vancouver Sun lamented, “Today our two nations of kindred blood and tongue draw near in common sympathy. For that great and good man who passed stole into our hearts as few have done before.”

The Vancouver Daily Province wrote, “The activities of [Harding’s] two years in office seemed but a prelude of a notable administration, in which the United States would attempt the solution of many domestic problems, and make a worthy contribution toward the peace and progress of the world.” Nor was his visit forgotten.

On 16 September 1925 the Harding International Peace Memorial was dedicated in Stanley Park almost on the spot where he had made his friendship speech two years earlier. Paid for by the Kiwanis International, the imposing semi-circular structure is thirty-seven feet in total length, and contains a commemoration to Harding’s visit, with an excerpt from Harding’s Stanley Park speech cut into two stone tablets.

Yet there is a paramount irony. Among many American historians, Harding is regarded as one of the greatest presidential failures. Today, his short term of office is often remembered more for scandal than accomplishment. Only after his death did the shadier side of the Harding administration become open knowledge.

Most damaging to Harding’s reputation was the conviction in 1929 of his first Secretary of the Interior, Albert Fall, as a result of the famous Teapot Dome oil lease fraud. Fall eventually went to prison, but the Teapot Dome affair was not an isolated incident. Many other important political appointees, some personal friends of the president, either fell before the judge’s gavel or died by their own hand rather than face the consequences of their impropriety.

Harding was not personally implicated in wrongdoing, but that alone could not absolve him of responsibility for political corruption on such a grand scale. At the time of his visit to Canada, the taint of scandal had not yet touched the president, but as Harding’s stature has diminished, his words on peace and friendship have passed from memory.

Today, the visit of President Warren G. Harding to Canada is recalled by the large monument in Vancouver’s Stanley Park, but to most Vancouver citizens its significance is obscure. Harding’s words cut into the granite tablets seem out of context. They are the words of a man only dimly remembered.

They do not tell the story of that day in 1923, when Vancouver accorded an American president one of his last great welcomes. In the city of his triumphant visit, Warren Gamaliel Harding is all but forgotten.

We hope you will help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!